On busy weekends in spring or fall, more than a thousand people will set off from one of three key trailheads to hike the Grand Canyon from rim to rim—a number that has been climbing steadily for years. They’ll cover a total of 21 to 23.5 miles, depending on the route they choose, dropping some 6,000 feet to the canyon floor, where temperatures frequently exceed 100 degrees and sometimes hit 120, then climbing back out. On peak weekends, so many rim-to-rim hikers will call for help that every paramedic ranger in the national park has to be called into action.

For that reason, the park’s Preventive Search and Rescue team has been trying get a better handle on who undertakes R2R crossings and what their typical behavior patterns and physiological responses are. A in the journal Wilderness & Environmental Medicine, by researchers at the University of New Mexico working with park staff, offers some data that will be useful for anyone who’s contemplating doing the hike.

On two weekends in May and October 2015, typically the busiest months, the researchers hung out at three trailheads (the South Kaibab and Bright Angel trails on the South Rim, and the North Kaibab trail on the North Rim), as well as the midway point at Phantom Ranch on the canyon bottom. A total of 617 hikers filled out forms giving information on their preparation, demographics, fatigue levels, and other factors. Here are some highlights from the data.

The hikers had an average age of 43, were 65 percent male, and (perhaps surprisingly) had a mean BMI of 25.3, right at the border of overweight. A lot of them had prior experience: 40 percent of them had done the R2R hike before, and 33 percent had done it at least 5 times. One person reported 46 previous crossings.

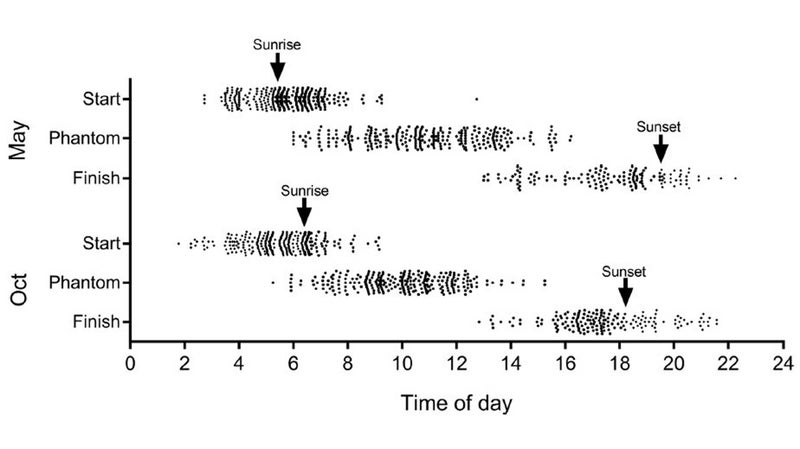

The median time taken to cross the canyon was 11.9 hours, with most people starting around sunrise (average time 5:30 a.m.) and finishing just before sunset (average time 5:30 p.m.). You can get a sense of the range of starting and finishing times from this graph:

Interestingly, that median time was identical for northbound and southbound hikers, even though the north trailhead is about 1,000 feet higher than the south trailheads. The split times, however, were quite different. Southbound hikers took 5.8 hours to go down, then 6.1 hours to go up; northbound hikes zipped down in 4.3 hours, but then had to slog upward for 7.6 hours. Neither descending nor ascending for hours on end is easy on the body, so it’s not obvious which is harder. Pick your poison.

There’s quite a bit of analysis of hydration strategies. About half the hikers used both a bottle and bladder, while 20 percent used bottle only and 31 percent used bladder only. The researchers aren’t fans of the latter approach: “We consider the singular use of hydration bladders in the desert to be high risk because the tough and spiny desert environment has ample opportunity to pierce the sides of a hydration bladder.”

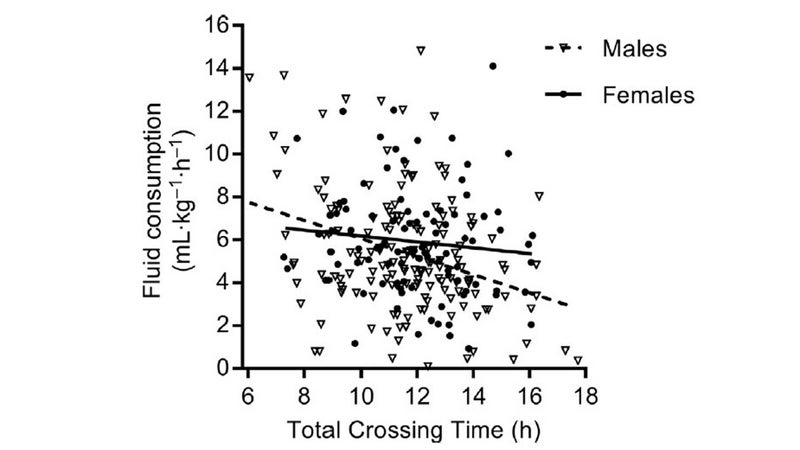

Overall, the hikers drank an average of 3.3 liters (112 ounces) of fluid, but there was quite a wide range. A quarter of respondents drank less than 1.1 liters, while a quarter drank more than 5.1 liters. Interestingly, women drank at a relatively consistent rate regardless of how long they took to complete the hike, averaging 5.5 milliliters of water per kilogram of bodyweight per hour. Men, on the other hand, didn’t necessarily drink more if they were out there for longer.

That difference shows up in the graph below, where the rate of fluid consumption for women is a relatively straight line as a function of total crossing time, while for men it’s a line sloping downward:

This graph also shows that the fastest hiker in the study took just over six hours. (For comparison, ultrarunner Taylor Nowlin recently ran R2R2R—that is, all the way across the canyon and back—in a new women’s fastest known time of seven hours, 25 minutes, and 58 seconds. The men’s record of 5:55:20 is held by Jim Walmsley.) And it also shows that several people, all men, seem to have drunk next to nothing for the entire hike, even if they were out there for 18 hours. You kind of have to wonder whether those guys understood the question or knew the dimensions of their water bottle.

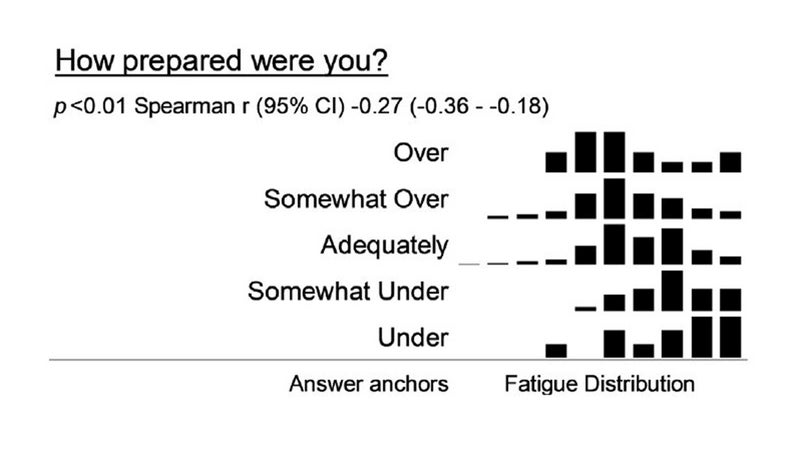

Finally, how hard is this hike? On a scale of 1 to 10, the median level of self-reported fatigue was 7, which corresponds to “strong fatigue.” But there were some nuances. Here’s how the levels of fatigue at the end of the hike panned out depending on how well-prepared the hikers reported being:

It’s tiring for pretty much everyone. But not surprisingly, it’s most tiring (as indicated by the bigger bars on the right-hand side) for those who were the least prepared. So if you’re going to hike R2R in the Grand Canyon, do yourself—and the poor overworked rangers—a favor by getting fit, planning well, and wrapping your hydration bladder in a cactus-proof protective coating.

My new book, , with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell, is now available. For more, join me on and , and sign up for the Sweat Science .