The Mountains Weren’t Enough for Marine Dan Sidles

As America wrestles with high rates of suicide among military personnel and veterans, outdoor programs have been offered up as a promising treatment. Dan Sidles seemed like the ideal candidate: an Iraq War vet who suffered from PTSD, he tried to find a renewed sense of purpose through climbing and mountaineering. Ultimately, it wasn’t enough. Brian Mockenhaupt explores the final years of a tortured friend.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide or self-harm, call the toll-free from anywhere in the U.S. at 1-800-273-8255. (To reach the , press 1.)

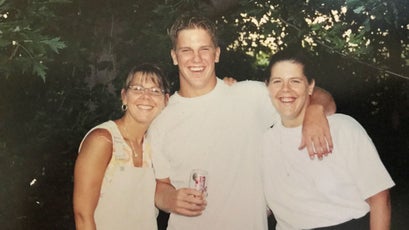

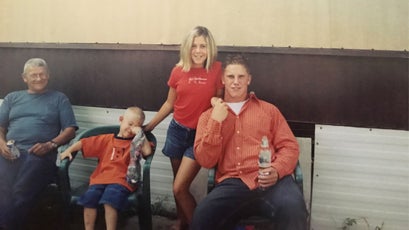

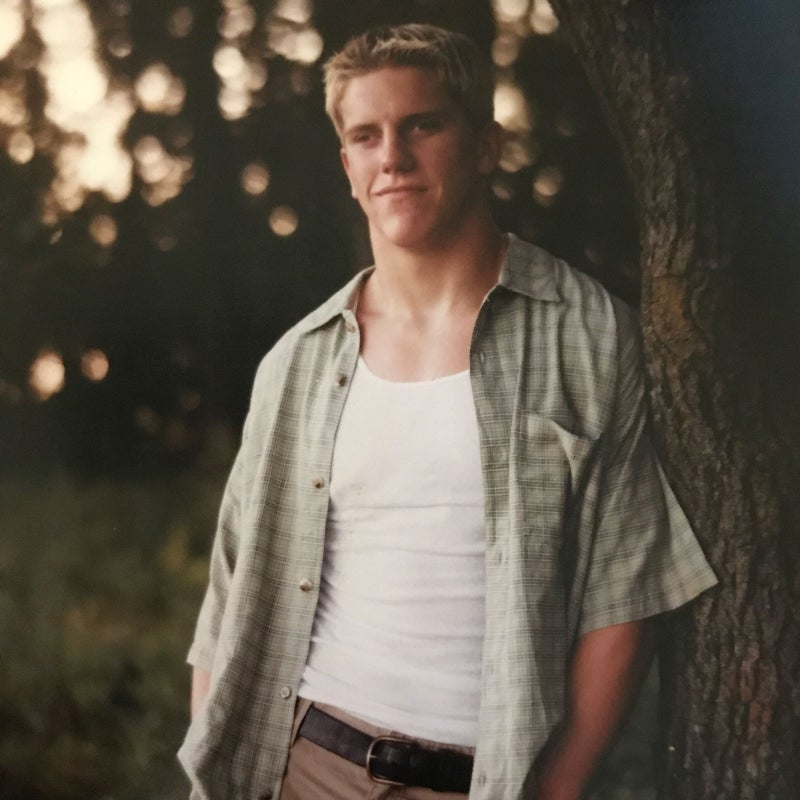

Dan Sidles grew up in northern Iowa, where the cornfields stretch to the horizon without a blip of elevation and the roads run bullet straight for miles through towns like Pocahontas (“the Princess City”) and Mallard (“We’re friendly ducks”).

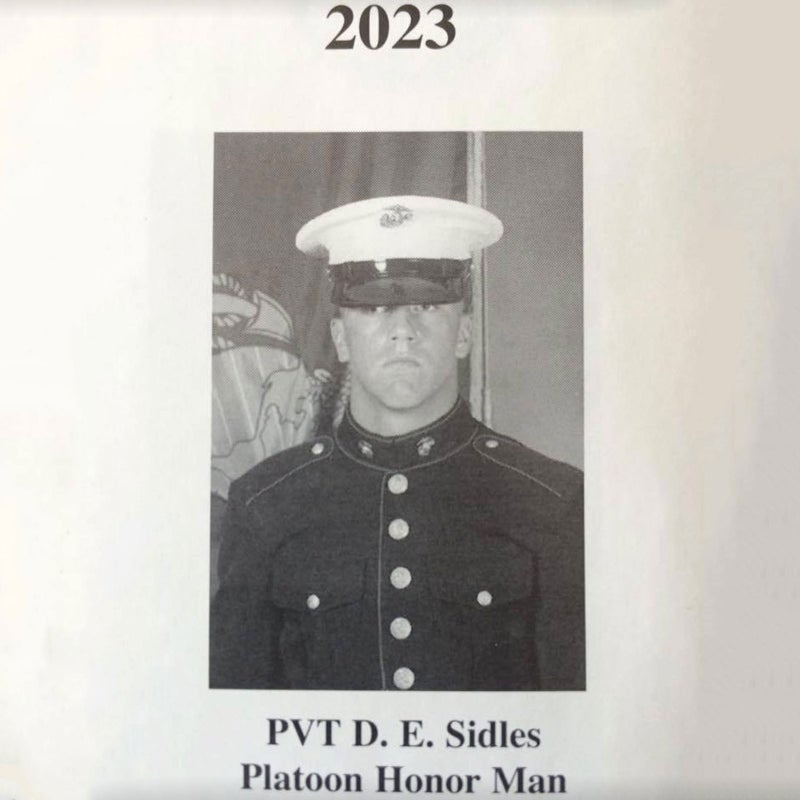

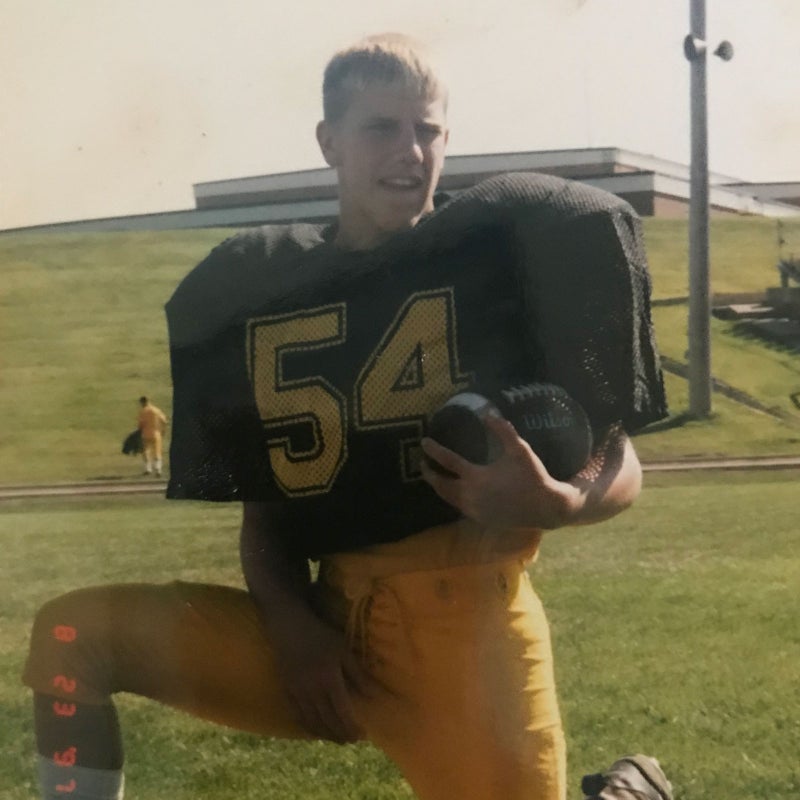

He detasseled corn in those fields in the summers and hauled beer kegs out there with friends. He wakeboarded on Five Island Lake and played football for the , where he was a standout on offense and defense. After a directionless year in community college, he left Iowa for the Marine Corps in 2001.

His older sister still lives in the area, and I stopped by her house to pick him up. “I have Daniel ready for you,” Amy Gilderhus said and handed me a small Folgers coffee container with strips of duct tape securing the plastic lid. The weight surprised me, heavier than I had imagined. An urn decorated with an American flag held the rest of his ashes; it sat on a living room shelf next to a picture of Sidles and a large frame that displayed a folded flag and his medals from the Marines.

Gilderhus wanted some of her brother’s ashes spread on the mountains he had climbed, the places where he seemed happiest. I had offered to help get them there, together with some of Sidles’s other friends and climbing partners.

We started a few weeks later, on a July day in 2016 in the , the giant slabs of tilted sandstone that rise up along the western edge of Boulder, Colorado. They were a favorite climbing destination for Sidles. He’d scrambled up them scores of times, usually alone, wearing his earbuds and a red bandana, and often shirtless, revealing a thickly muscled tapestry of tattoos.

I had climbed the Second Flatiron with Sidles a few years earlier. That was my first time on something so high without a rope. I begged off the last short stretch, which required a move back onto the face near the top—heady for a new climber. Sidles continued, breath quick and heart drumming. Afterward he wore a giddy smile, still riding the adrenaline spike. “I haven’t felt like this since the last time I was in a firefight,” he said.

Now I started up the slab again, with a half-dozen others who had shared climbs with Sidles. Just ahead of me, Erik Weihenmayer, the , danced his hands across the rock and settled on a hold. In 2010, he and several friends from that Everest expedition had guided 11 wounded Iraq and Afghanistan veterans up a 20,075-foot peak in Nepal. I wrote about the expedition for ���ϳԹ���, which is how I met Sidles. We spent hours talking on the trail. He was curious, self-aware, and determined to find some peace in his life. A natural storyteller, he punctuated the serious with humor and a laugh that a high school friend described as “a little girl getting licked to death by puppies.” Of the veterans—a mix of men and women with amputations, traumatic brain injuries, and post-traumatic stress—he seemed to be the person who gained the most from the trip. Sidles reveled in the physical challenge and believed that the outdoors might offer him a way forward.

In Nepal and afterward, Sidles spoke with remarkable clarity and insight about himself, his motivations and shortcomings. He knew that he’d been self-destructive and mired in self-pity after two tours in Iraq, and that many who cared for him had suffered because of it. He spoke not as someone lost in the darkness but as one emerging into the light. “I’m not going to give up, even on the roughest days. I don’t want to be a statistic, someone who resorts to doing drugs and drinking my face off to deal with my problems,” he told me. Perhaps other veterans would find some hope in his story. “Maybe they’re thinking about hurting themselves,” he said. “Before they run for the razors, maybe they’ll run to someone who can get them into something like this.”

He went on to climb in Ecuador, Alaska, and across the West. He summited in Russia and in Argentina. Gilderhus figured she might get a call one day that Sidles had been in a terrible accident in the mountains. An avalanche. A fall. But not that he’d killed himself.

I didn’t ask why. Few of us did. We knew Sidles had been struggling. But plenty of questions remained. He had participated in so many outdoor programs, most of them geared toward veterans and meant to help them reintegrate, find fellowship and purpose, and overcome some of war’s damages. For years he’d used the health care services offered by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Why hadn’t he seen more progress?

Many of those who knew him thought they’d failed him. Had they? Had the VA failed him? Had the country failed him, with its inability to understand what people like Sidles lived through?

Was this conclusion inevitable—dead at 34, a decade after he’d taken off the uniform? Or might things have turned out differently? And might his story tell us something about how to heal other combat veterans? To know that, I needed to understand what had happened to him.

But first we would return some of Sidles to one of his favorite places. After 1,000 feet of mellow climbing, we gathered near the top. Matt Murray opened a sleeve of Clif energy chews and passed them around, a toast of sorts. “Dan ate these like candy,” he said. Bald-headed, with a booming baritone voice, Murray flew A-10 attack jets in the first Gulf War. He had climbed with Sidles occasionally for the past several years, but mostly he had been his friend’s unwavering supporter. Sidles had twice lived with Murray and his wife for several months.

I pulled a small glass jar from my pack, containing a portion of Sidles’s remains that his sister had given me, and handed it to Murray. He tipped the jar and pale ash poured out. Some lifted on the breeze. Pebble-size pieces of bone and teeth tinkled down the rock face.

“There he is,” Murray said. He dragged his fingertips across the fine gray pile, then rubbed them together.

I have known several veterans who killed themselves, and many more who tried, some of whom I served with in Iraq in the Army infantry, and others I’ve met since. It sometimes seems I know more combat veterans who have considered suicide than haven’t.

kill themselves every day. While that tally presents the problem in scale, it obscures the fantastic complexity of each story. Cure a disease and millions might benefit from the same protocol. Not so for suicide, its causes and preventions so highly personalized. There can be myriad factors unrelated to war or military service: crumbling relationships, lost jobs, terminal illness, depression. And what pulls one veteran back from the edge might not help the veteran sitting next to them.

Despite the common portrayal of service members and veterans who die by suicide as young and battle scarred, most recent victims did not serve in Iraq or Afghanistan. According to , 65 percent were aged 50 or older when they died—though they could still have been dealing with combat trauma, which sometimes doesn’t manifest for decades. Among the younger veterans, who die by suicide at a higher rate than older veterans, more than half didn’t go to war. And of those who deployed, many didn’t see heavy combat.

But Sidles did.

Assigned to weapons company, , he rolled into Iraq on March 20, 2003, in the turret of a Humvee. The .50-caliber heavy machine gun he manned fired half-inch-thick bullets that could tear a man in half and shear off limbs. Twenty-one years old and a couple of hours into his war, he shot up a car full of fighters, sending it off a bridge and into the water. He’d fire more than 1,000 rounds on that first day of the invasion. He and his friends fought north toward Baghdad, the invasion wound down, and they went home, where they drank themselves senseless and acted the part of victorious Marines, cocky and belligerent.

Sidles and two buddies all got the same tattoo: Unscarred. After surviving the war, they imagined themselves untouchable. Sidles got another postwar tattoo, inked across his chest: Laugh Now, Cry Later. “Looking back,” he told me, “it’s almost like I had the feeling that what we were doing over there was going to haunt me. The first time was so easy compared to what happened the second time. We used to laugh and be filled with pride when we killed. Then you get out and no one understands how you could do that. People you would die for think you’re a psycho, and that makes you cry.”

The following spring, Sidles was back in Iraq, this time outside Fallujah, a city boiling with tension. Days after he arrived, , killing them, dragging their charred bodies through the streets, then stringing them from a bridge over the Euphrates river. Sidles’s unit went out that night and cut down the corpses.

In response to the killings, the Marines encircled and then pushed into Fallujah to clear it of insurgents, engaging in house-to-house fighting. On the city’s outskirts one afternoon in April, Sidles and two other Marines climbed atop a tower with an M240G machine gun and several belts of ammunition to observe enemy movements. But on the flat roof, in the full light of day, they were observable, too, with barely a concrete lip for cover. As they settled in, gunfire erupted from buildings and streets to their front and on both sides. Bullets snapped overhead, inches away, and several rocket-propelled grenades whooshed past, just missing them. If they stayed on the roof, they would die. The only way down was a ladder exposed to all that gunfire. Sidles ordered the other Marines off the roof while he covered them. He’d soon shot through nearly all 400 rounds, and he didn’t see how he’d get down alive.

“I just accepted the fact that I was about to die. And when you do that, when you believe that, your life goes poof!—right in front of your face,” he told me one morning in Nepal as we sat on a stone wall outside a mountaintop monastery. “Every choice I had made in life led me to that rooftop, and it was all over. I don’t think you’re ever the same after that. A piece of you is taken.”

As bullets pinged around him, Sidles scurried down the ladder and made it to safety. He still had six months to go.

Most U.S. combat deaths and injuries in Iraq were a result of improvised explosive devices. Insurgents hung them from highway overpasses and stuffed them into dead dogs along the road. They hid them in trash piles and car trunks, and most often, they buried them in the dirt. One of these exploded under Sidles’s truck on a scorching-hot July day. The blast burned and bloodied his face, mangled the medic’s arm, and took off the gunner’s hand. What Sidles would remember most, for years, was the terrible screaming.

As he walked into the chow hall hours later, with his own blood and that of his friends still on his uniform, a senior Marine told him he’d need to change before entering. The pettiness and lack of understanding enraged Sidles.

On his next patrol, four days after the blast, another Marine in Sidles’s Humvee noticed a battery half-buried near where they’d parked. He dug in the dirt. “Dan, we’ve got to go,” he said. “We’re on top of an IED.”

The bomb had malfunctioned. The truck’s weight had engaged the pressure plate, which should have ignited the massive artillery shells buried beneath it. The disposal team later told them that had the IED exploded, they’d all be dead. “What do you do? You just shake it off,” Sidles told me. “You can’t dwell on that stuff. Until years later, when it starts to really set in, what you’ve been through. That’s when it starts to screw with you.”

He spent his last year in uniform instructing new recruits in rifle marksmanship, then returned to Iowa. In the Marines, he and his buddies had relished their image as fighters and killers. Back home, in a world where people didn’t understand where he had been or what he had been doing on their behalf, the ground seemed to shift. Sidles, who had grown up with a lazy right eye, was already sensitive to people’s stares. Now it was all he could see. Judgment. He compared himself to a tiger on a chain, gawked at by strangers: “ ‘Hey, he’s been to combat. Want to go talk to him, want to go touch him?’ You just feel like this wild animal, and it’s like, oh man, I’m a human being.”

“Looking back,” Sidles told me, “it’s almost like I had the feeling that what we were doing in Iraq was going to haunt me. We used to laugh and be filled with pride when we killed. Then you get out and no one understands how you could do that. People you would die for think you’re a psycho, and that makes you cry.”

He’d sit in a bar in Emmetsburg, wearing a brooding mask of meanness, and wait for someone to start eyeing him. Drunken fights became a pastime. He spent a few nights in jail and missed out on more because the cops knew him and knew he’d been to war.

He still hung out with a few close friends from high school, but those trusted relationships had changed, too. James Davis, for one, felt a yawning distance. “He was talking to me, telling me a story, but he was just looking right through me,” Davis said. Sidles told him that people didn’t understand how crazy the war had been or how hard it was to readjust to life afterward. “It felt like a script he gave people,” Davis said. “Like he was trying to placate me.”

“He’ll always be my best friend,” Sidles told me. “He’ll bring up things that, no matter how many times he said it, always made me piss my pants. And now when I’m back, he’ll bring it up: Remember that time? And it’s not even funny to me. For him I’ll try to fake it. But he can tell.”

Sidles knew he was alienating people but felt helpless to stop the spiral. A drunk-driving charge earned him two weeks in jail. “I was throwing my life away, but I didn’t know why,” he said. “I didn’t know what was causing it.”

He moved from Iowa to Phoenix, but the change didn’t help. He couldn’t escape the aimlessness and boredom. Nothing matched the terrible excitement of the war. His social worker at the VA had an idea. She connected Sidles with Weihenmayer, who invited him to join the team that would climb Lobuche.

War veterans have long found relief in the solitude, perspective, and physical challenge of the outdoors. Earl Shaffer, who fought in the Pacific in World War II, told a friend he was going to “walk the Army out of my system, both mentally and physically” and became the , in 1948. Paul Petzoldt, who started the (NOLS), fought in Italy during World War II with the Army’s storied Tenth Mountain Division, as did , the first executive director of the , and the founders of several American ski resorts.

with a formalized program meant to calm the mind and salve the wounds of combat. Rheault fought in Korea and Vietnam with the Special Forces and retired in 1969 in a haze of scandal after his men killed a South Vietnamese double agent. He retreated to the outdoors and worked at the in Maine for 32 years. In 1983, he started a program for Vietnam veterans that promoted the physical challenge and camaraderie of the military in the mountains of New Hampshire. “We need each other to share the heavy loads, to help a vet who is hurting, to lend a hand across a dangerous or difficult spot in the trail, to make camp in the wild,” he wrote in . “The experiences duplicate everything except the shooting, the wounding, and killing.”

Despite promising results, nature-based programs for veterans didn’t gain wide interest until the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan gave us a new generation of struggling veterans. Today that landscape is crowded with groups offering everything from sailing and surfing to horseback riding and ice climbing. Many of these programs are event based, not built around continued engagement. Some are meant just to be fun outings, a “Thank you for your service.” Others, like Weihenmayer’s group, have more elaborate ambitions to ease PTSD symptoms and help the injured overcome limitations.

For the Nepal expedition in 2010, Weihenmayer and his climbing buddies reasoned that mountaineering could mimic the best parts of military service: teamwork, a sense of mission, and a shot of adrenaline. That’s what Sidles found when he strapped on a pair of crampons and slogged toward the Lobuche summit. He liked the rush he felt in the mountains, outside his comfort zone, a little bit scared and not wanting to let down those around him. “It takes courage to face your fears,” he told the filmmaker Michael Brown, “and if there’s no fear, there is no courage, you know what I’m saying?”

Brown, who has summited Everest five times, ran what was then called the . Students usually made their own short movies during multi-day backcountry trips, but on the Nepal expedition they all worked together to film the veterans. The resulting documentary, , prominently featured Sidles. After the expedition, Brown interviewed Sidles in Phoenix and filmed him in a boxing gym. Murray, a longtime friend of Brown’s, had climbed with us in Nepal and helped Brown with the follow-up interviews for the film.

“I feel like now that I know what I’m capable of, I just want more,” Sidles told them. “That feeling of just being alive.”

Brown and Murray both lived in Boulder and encouraged Sidles to relocate to Colorado. A few months later he moved into Murray’s basement, with mountains now in his backyard. He started climbing with a friend of Murray’s who had taught bouldering and mountaineering at NOLS. Sidles wanted to work as a guide and figured that attending NOLS could be a good route. He enrolled in the outdoor-educators course—three months of skiing, canyoneering, climbing, and wilderness first aid meant to prepare students for outdoor careers. That program now draws two dozen vets a year; Sidles, who used his GI Bill benefit to pay for the course, was one of just two who took part in early 2012.

Kyle Drake, a field instructor that semester, was Sidles’s adviser. Sidles told him about the Marines, his time in Fallujah, and the years that followed. Most of the other students were just out of college, and at times Sidles grew frustrated with their immaturity. He argued with a fellow student during a skiing exercise, so Drake positioned himself near Sidles, should he need to intervene. “I wasn’t sure what his life experiences had done to him,” Drake told me. “Is he a ticking time bomb, or is he just going to be angry?” But Sidles knew he needed to remove himself from the situation and find release through exertion. Duckwalking in his telemark skis, he charged ahead, dragging his sled—upside down—through the snow.

“Hey Dan,” Drake called. “Do you need help?”

“No,” Sidles said. “I’m good.”

During the canyoneering section, with two weeks left in the semester, Sidles again argued with a fellow student. In the Marines, that sort of confrontation—stern voices and threats—wouldn’t have raised an eyebrow. But this one, while not physical, concerned the instructors enough that they sent Sidles out of the mountains early. NOLS awarded him a certificate for completing the course, which was necessary for the VA to reimburse the cost under the GI Bill.

The chance to use his new outdoor skills came soon after. Weihenmayer organized another expedition for wounded vets, this time to Ecuador’s 19,347-foot Cotopaxi. Several veterans from the Nepal trip, including Sidles, would serve as mentors. Matt Burgess, a military policeman who fought in Iraq, credits Sidles with keeping him on the expedition. Disillusioned by the physical demands, Burgess had wanted to quit. Sidles told him of his own doubts in Nepal. “He’d pull me aside on a daily basis. ‘You doing OK? You still glad to be here?’ ” Burgess told me. “At one point I fell and slipped. It was Dan who stopped me. Knowing he was there and had my back was extremely comforting.”

During the canyoneering section of the NOLS outdoor-educators course, with two weeks left in the semester, Sidles again argued with a fellow student. In the Marines, that sort of confrontation wouldn't have raised an eyebrow. But this one, while not physical, concerned the instructors enough that they sent Sidles out of the mountains early.

Weihenmayer and the other guides from the Nepal trip had all summited dozens of other challenging mountains. They knew the stresses of expeditions. For the veterans, they surmised, success in the mountains could be taken back to their daily lives. “We were overconfident. We tried it again, and the whole thing almost fell apart,” Weihenmayer said of the Ecuador trip. “There’s a fine line between an adventure and the chaos of retriggering some of the wounds they were there to fix.”

In a lodge halfway up Cotopaxi, Sidles and another veteran mentor nearly came to blows over Sidles’s contention that the other man wasn’t pulling his weight. Sidles also had strong words for the guides, who he felt were underprepared. That day a guide had misjudged a route, turning a four-hour acclimatization hike into an all-day grind. The rancor soured the overall mood, which worsened a few days later when only half the group summited. “We should have been more prepared,” Weihenmayer told me.

His group, now called , has since run dozens of veteran trips. They’re done on a smaller scale, with an emphasis on the overall experience rather than reaching the summit. The staff receives three days of suicide-prevention and crisis-management training, and a staff social worker checks in with the veterans before the trip and for several months afterward to see how they’re integrating the experience into their daily lives.

The problems on Cotopaxi highlight the shortcomings of some programs, which can be heavy on good intentions and skills acquisition, but light on mental-health expertise and a deep understanding of the physical and psychological issues veterans often face. And many of the programs might not be reaching those who could most benefit.

“It’s much easier to work with a veteran who has his shit together, who shows up, has a good time—you can take some pictures, and you don’t have to deal with them again,” Joshua Brandon told me. Brandon used to run the program, which takes veterans mountaineering, rafting, climbing, and fishing. Most of the vets who came on his trips didn’t have what Brandon calls “hardcore” issues. “It’s the guys and gals who are the most self-destructive, and destructive to the people around them, who are the most work,” he said, “but they also need the most help. And they’re the ones we should be helping.”

Brandon met Sidles on a climbing trip and thought he could be a good leader for the Sierra Club’s program. He understood Sidles’s struggles—the alienation, despondency, and wrecked relationships. He had dealt with the same challenges after three combat tours in Iraq, which earned him a Silver Star and two Bronze Stars with Valor. He and some fellow soldiers taught themselves to climb on Washington’s Mount Rainier and found that the adversity, risk, and teamwork eased their minds in ways therapy and medication alone couldn’t.

But while therapies like yoga, meditation, and virtual reality have been validated by studies and utilized by the Pentagon and the VA, there has been little research about the benefits of nature for veterans. In a for the Sierra Club, in which veterans participated in canoeing, rock-climbing, backpacking, and skiing trips, the 98 subjects reported improvements in psychological well-being, more social connectedness, and a more positive life outlook, though a month after the trips the benefits had largely dissipated. “Nature is a momentary fix,” Brandon said. “Much like medication, you have to keep dosing.”

Twenty veterans kill themselves every day.

Brandon left the Sierra Club but still puzzled over how best to reach veterans like Sidles. He believes that ongoing outdoor experiences built around tight community and self-examination, rather than just escape and thrill, can help. Working with a team of researchers at the University of Washington—and backed with a $100,000 grant from REI and additional support from —Brandon designed a pilot study that started earlier this year. Veterans recruited from the Seattle area met regularly for small-group excursions and casual social gatherings to augment traditional treatments and medication.

If the results are positive, Brandon hopes to see programs like this incorporated as a core element of treatment protocols. But he recognizes the difficulty of shifting institutional mindsets and working with volatile veterans. “You really have to care about someone to put up with some of that, to fight through and not take offense at some of their bullshit,” Brandon said. “It’s the same issues we’re trying to help them with that are causing them to lash out at friends and family.”

For Sidles and many vets like him, it’s not just the combat that wrecked them. While his battlefield experiences alone would have been enough to twist his sense of self and derail his relationships, Sidles’s war started long before he set foot in Iraq.

“I taught myself to tie my shoes, for fuck’s sake,” Sidles told Brown in a documentary interview. No one bothered to show him, and he feared asking for help, so he figured out his own system of loops and knots, which carried through to adulthood. He was the youngest of four siblings by eight years, with 16 years between him and his eldest sister. “My dad pretty much told Daniel that he was a mistake,” said Gilderhus, who is 48. “He didn’t have parents. They were old and sick.”

Their father had a heart transplant in 1998, and their mother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis around that time. To be closer to medical care, the family moved from Graettinger to nearby Emmetsburg, a town five times bigger, with 4,000 people. In high school, Sidles excelled in sports, but academics came harder. “You got this douche dad who says, ‘You’re a no-good punk who’s not going to amount to nothing,’” he said. “A test or something comes up in school, and you say, ‘I’m not going to study, what’s the point? I’m just going to fail. My dad tells me that all the time.’ And then what happens? You take the test and you fail. And he gets the report card and says, ‘Yeah, that figures.’”

Neglect and emotional abuse, shaping a kid’s sense of identity and self-worth, can damage them as much as physical or sexual trauma. To gauge exposure to these negative events, mental-health providers use a ten-question survey about family instability and incidences of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. Divorced parents? One point. Parent in prison? Another point. Two questions stood out to me as particularly relevant to Sidles: “Did a parent often swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you?” and “Did you often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special?” Based on what I know of Sidles’s childhood, I figured his score at a four.

Male veterans of today’s all-volunteer military as their civilian counterparts to have endured difficult childhoods, which wasn’t the case during the Vietnam War, when the draft selected more broadly from the population. (Female veterans and civilians have similar numbers of negative childhood events, and while female veterans are half as likely to kill themselves as male veterans, they’re more than twice as likely as female civilians to do so.) Many people, like Sidles, join the military to escape a crappy home life and for the camaraderie and opportunities they didn’t have growing up. But unresolved childhood trauma can stack the deck and cause bad experiences later in life to do far more damage. “The guys who come in with a lot of emotional baggage, it just gets compounded, especially with combat tours like we had,” Ryan Thompson, Sidles’s section leader during his Iraq deployments, told me.

Compounding trauma increases the likelihood of suicide. of male veterans in an inpatient program for combat-related PTSD, more than 40 percent reported four or more adverse childhood experiences. Those with a greater number of ACEs were significantly more likely to have thought about suicide or tried it. But if the military screened out those with bad childhoods, it would lose an enormous chunk of the recruitment pool. The services have a hard enough time filling their ranks. Most young Americans——a���� , too sick, or perform too poorly on aptitude tests for military service, or they have disqualifying histories of crime, drug use, or mental illness.

In many ways, Sidles was an ideal recruit: strong, driven, devoted, and searching for belonging. The Marines offered him respect, adventure, and a sense of purpose and worth far from small-town Iowa and far from his family. If he had had a different job in the military—say, helicopter mechanic—things might have turned out much differently. He’d be a couple of years from retirement today. But he chose the infantry.

“I adapted to war really well,” Sidles said. “A lot of people who join the military come from broken homes like me. I’m no exception. So you’ve got some anger. You can’t deny that. It’s there. And then the Marine Corps just adds to that.”

Sidles felt bullied by his father and elder brother, and he considered terrorists the biggest bullies of all, so he channeled that anger. Friends who were injured or killed stoked the flames. “The fire just keeps burning and burning and burning,” he said. “And then you come back here and try to put it out, and it’s, like, impossible.”

During my two Iraq tours with an Army infantry company, I had some close calls, but I didn’t see anything like the combat Sidles did. Even if I had, my upbringing better prepared me to deal with the ramifications. I left for war knowing that my family loved and supported me, and I returned to the same. Within several months my violent dreams, startled responses, and irritability eased as my mind readjusted to life outside a war zone.

Sidles didn’t come home to that kind of safe harbor. “The love I didn’t get at home I got from my friends. I felt that a lot in the Marine Corps,” he said. “There’s no situation that’s too tough as long as you have people who care about you, and you care about them, to go through it with you. Once I got out of the military, I realized I was really, really on my own.”

In 2014, Sidles spoke before 50 people at an ice-climbing event in Ouray, Colorado, and though he was racked with nerves, the talk went well. But the rhythms and demands of everyday life confounded him. “Dan seemed like he was still a gunner in Iraq,” Nick Watson told me. “He was just stuck there.”

His own choices may have led him to that rooftop in Fallujah— most prominently, enlisting in the Marines—but other factors beyond Sidles’s control played a part, too. He understood this, and it fueled his resentment toward his father. “He told me I would never make it in the Marine Corps, I wouldn’t even make it through boot camp,” Sidles said. “I did two combat tours, Purple Heart, awards that say things like courage under fire, and he tells me I did nothing in Iraq.”

“Daniel wanted one thing from my dad: a sincere apology,” Gilderhus recalled. “For everything.”

“You don’t have to forget,” she told her brother, “but you might have to forgive a little to go on.”

Sidles tried to repair the relationships, but it was short-lived. Family wounds aren’t easily mended, and the hurt ran deep. His mother, for whom he cared greatly, died while he was living in Phoenix. His family didn’t call. A friend told him several days later. He wanted to confront his father at the funeral home, but Gilderhus stopped him. She invited him to her home for Christmas. Trying to navigate the bitter family emotions, she decided to have a gift exchange with her father at her mother’s graveside, then celebrate with her brother later. But Sidles learned of this. He drove to the cemetery, saw his father, and kept driving. After an argument with Gilderhus that night, Sidles left. The last of the frayed family threads had snapped.

I last saw Sidles in July of 2013 while in Boulder for Michael Brown’s wedding. The morning of the ceremony, I climbed the with Murray. We were just starting the initial pitch when Sidles passed by on the trail, hiking down from the top. I called to him, but he didn’t hear. Or maybe he did. He just kept charging down the path.

Later I sent him a text asking if he’d like to get a beer and catch up.

“Fuck no,” he wrote back. “I’ll go ahead and skip story telling time.”

The message stung. Storytelling time. I read this as an indictment: he saw me not as a friend but as a journalist, someone else who had taken advantage.

“He thought we used him,” Brown said. “And we did.”

Like Brown, my relationship with Sidles began as a lopsided exchange. Journalists and filmmakers are gatekeepers of our subjects’ most personal experiences, and the transaction is tilted decidedly against them: Tell me your story, with all its intimate, painful, and embarrassing details, and I’ll share it with the world. The interview itself can retraumatize, a possibility I wrestle with routinely when writing about people who’ve been emotionally and physically scarred. For this they receive no compensation, only the possibility that someone somewhere might be exposed to their story and moved by it.

When he first saw my ���ϳԹ��� piece about the Lobuche climb, Sidles worried about how others would view him. “Then I had gotten a couple hits on Facebook from a couple guys who had been to combat,” he told Brown, “and they basically told me that they felt exactly how I felt, and it was almost like a thank-you for speaking up.” This prompted Sidles to open up more for the documentary. “Instead of worrying about how I was going to look,” he said, “I threw that aside and said, You know what? I’m going to be honest. I’ll let people see how I live and how I think.”

I helped with some of the editing, and as we reviewed the footage, Brown mentioned several times that he wished he could make a whole film about Sidles, so eloquent, honest, and funny were his reflections and insights. We both loved spending time with him. “If he smiled or laughed, and you were at the other end of that, it was the best feeling in the world,” Brown said.

He showed Sidles the documentary before almost anyone else had seen it. “Yeah,” Sidles told Brown. “It’s all true.” But he came to regret his involvement. He felt like some of the guides on the trip had used him as a prop—look how we’re helping these wounded veterans. He also nursed resentment toward some veterans in the film who hadn’t been wounded in combat or, he felt, had embellished their experiences.

Though the infighting on the Cotopaxi expedition had exacerbated these frustrations, Sidles continued to take part in veterans outdoor programs. He wanted the opportunities but seemed to resent it at the same time, as though his participation confirmed that he couldn’t help himself. Yet he believed that the outdoors had been truly good for him, and he wanted to use his experiences to help other vets. Climber , who cofounded the adaptive program , worked with Sidles to market himself to the professional climbing and outdoor-recreation communities. In 2014, Sidles at a Paradox ice-climbing event in Ouray, Colorado, and though he was racked with nerves beforehand, the talk went well, and he enjoyed the experience.

But the rhythms and demands of everyday life confounded him. He felt he had been at his best in Iraq, fighting alongside his brothers. Back home, where people’s reactions to him ranged from curiosity to wariness and concern, he seemed to long for the war’s simplicity and the sense of worth and purpose it brought him.

“Dan seemed like he was still a gunner in Iraq,” Nick Watson told me. “He was just stuck there. He never made that leap to having an identity in the civilian world, having something to get up and look forward to.” Watson, a former Army Ranger, runs Veterans Expeditions (), which has taken thousands of former military men and women climbing, rafting, mountain biking, and mountaineering. He linked up Sidles with a former special-operations Marine who runs rafting trips and offered to train Sidles as a guide. “I thought it was perfect,” Watson said. But Sidles didn’t last the day. Watson’s friend told him Sidles bristled at interacting with the younger guides.

Another friend of Sidles in Colorado had connected him with an assistant guiding job on Denali. I figured this could be a good step, moving him away from his primary outward identity as a war vet. As a guide he’d be expected to check his emotions, work with a team, mitigate conflict, and meet the needs of paying clients. But this turned out to be another false start. He enjoyed the work and got along well with clients, but he argued with the lead guide. He didn’t work another Denali expedition.

Watson climbed with Sidles several times over the years, both on Vet Ex trips and just the two of them. Sidles eventually cut off contact with Watson, but even before that, in the months leading up to Sidles’s decision to distance himself, Watson had sensed a shift. “The outdoors wasn’t fun to him anymore,” he said. “The thing that was keeping him going, he lost that.”

After texting me that afternoon in Colorado, Sidles sent Murray a note berating him for giving me his new phone number. “Every time I hear about you and everyone living their happy lives,” he texted, “it reminds me of what a piece of shit I am.”

Sidles stopped talking to Murray, apparent punishment for the breach of trust. He apologized months later, and their friendship resumed. Over the next two years, I often asked Murray about him, but I didn’t reach out myself. Before Sidles died, and many times afterward, I wished that I’d set ego aside and written to him or called, to let him know that I valued him as a friend and hoped to share a trail or rope with him again soon.

After the NOLS course, Sidles moved into an apartment in Gunbarrel, just outside Boulder. As he had while living in Phoenix and in Murray’s basement, he spent much of his time alone, playing guitar, watching history documentaries, and reading. When he was still talking to Gilderhus, he would sometimes call her late at night and tell her about episodes of Dr. Phil he had seen, how the analysis might apply to his own life.

He had worked for a few years as a personal trainer after the Marines and enjoyed the autonomy and the one-on-one interaction with clients. He couldn’t imagine himself in a regular job, beholden to a company’s norms, rules, and schedules and forced to deal with coworkers and customers. The VA agreed, deeming him unemployable, which qualified him for monthly compensation in addition to his disability benefits. Still, he wanted to work, and the verdict of his inability to support himself weighed heavily, Gilderhus said.

The gym offered refuge. For hours he lifted weights and exhausted himself with boxing drills, a Sisyphean attempt to quiet his mind. While living in Boulder, he scrambled up the Flatirons alone several times a week, sometimes every day. He often climbed the First Flatiron, where a fall, though unlikely for a decent climber, could be catastrophic. Climbing without a rope freed him from the need for a belay partner. He could climb when he wanted, without coordinating schedules, without judgments or expectations. But soloing also offered risk and thrill, the ever present what-if?

Sidles told his Marine buddy Adamn Scott that he liked the high stakes. “You screw up and you die,” he said. Scott sensed that this also bothered Sidles—being so drawn to the danger, the same craving they felt for the rush of combat.

“Don’t you ever get nervous being by yourself?” Scott had asked him. “What if something happens?”

“Who cares?” Sidles said.

Scott had been with Sidles through boot camp, infantry school, and both tours in Iraq. They shared the same Unscarred tattoo.

“When we first got out, I couldn’t function in society ,” Scott said. Every day a sight, smell, or sound reminded him of Iraq. He tried the VA, but like Sidles and so many others, he felt that the therapists couldn’t understand his time in combat and were more interested in medicating him. “What helped us the most was getting together and talking about it,” Scott said. Each summer he’d invite a half-dozen Marines to his house in Bloomfield, Iowa, for a few days of beers, grilling, and catching up. Sidles always attended.

Sitting around the fire, they talked about how they were getting by since they left the Marines. They talked about the war, and they talked about suicide. “We’d all thought about it,” Scott said. Sidles told him he’d never do it. “He called it the pussy way out,” Scott said. They had talked about it in Iraq, too, in a broader conversation about heaven and hell, and where they, as killers of men, might be headed. “Dan was of the understanding that you didn’t go to heaven if you commit suicide,” Scott said.

During a visit a few summers ago, they spent the day out on a boat, skiing, wakeboarding, and drinking beer. Back at the house, they drank into the night. In Scott, Sidles saw everything he didn’t have: a good job, a loving wife, kids, a house.

“Dude, your life is the shit,” Sidles told him.

“You could have this, too,” Scott said. He hoped Sidles would return to Iowa one day and buy a house near him.

“Nobody’s going to want me,” Sidles said. “I’m a broken old piece of shit.”

Scott wasn’t buying it. “I just chose not to be miserable anymore,” he told Sidles, and chided him for not being more grateful for what he had, traveling the world to climb mountains, often with other people funding the trips.

Then Sidles punched Scott, and Scott punched back, the two men bloodying each other’s faces.

Other Marines tried to reach him as well. After Sidles guided on Denali, he stayed for a few weeks with Ryan Thompson, his old section leader, who lives in Anchorage. They would spend hours talking. “He still had a lot of deep-seated anger,” Thompson said. Anger at himself for leaving the Marines and for getting arrested, which closed off job opportunities. Anger at civilians for not understanding him. Anger at his family.

“I had some pretty frank discussions with him about how self-destructive he was and how he needed to find a more positive path in his life,” Thompson said. “One time I even asked him: Are you going to hurt yourself? Are you thinking about suicide?”

“No,” Sidles said. “I’ve got too much fight left in me for that.”

Sending soldiers to war is far easier than bringing them home. More than 15 years of continuous warfare has flooded the VA with men and women struggling with physical and mental wounds. Of the 2.7 million who have deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, have been diagnosed with PTSD. They are often prescribed medication and offered one of two widely used treatments. In , the veteran writes a detailed account of a traumatic incident, like a bomb explosion that might be causing nightmares, irritability, and substance abuse. The story is recorded and then played back, over and over, until recalling the incident doesn’t cause distress. In , a veteran describes a traumatic incident, then discusses it with a therapist to identify irrational beliefs associated with the trauma, such as guilt that a bomb wasn’t spotted before it exploded.

. More than half of the veterans who start prolonged-exposure or cognitive-processing therapy don’t complete the 12-session regimen. And for veterans like Sidles weighed down by multiple traumas, focusing on one incident often isn’t enough. Plenty of veterans have received excellent medical and mental-health care. But with an institution so big, the demand so great, and individual needs so complex, not all veterans get the specific help they need.

Sidles didn't have the equipment, or money for a ski pass, so his VA doctor, Patricia Alexander, worked on getting him both. Others at the VA told her to stop, because it wasn't appropriate treatment. She refused. “It was totally appropriate treatment,” she told me. “He needed to be outside.” Sidles got the skis, but their next meeting was their last.

Sidles also complained about therapists who don’t know war—“like me giving mothering advice to a mother,” he said. Group therapy was hard for him as well. He wasn’t interested if it meant sitting in a circle with people who hadn’t been in combat pulling triggers. Each negative therapy experience compounded the problem: open up a few times, see poor results, and lose incentive to dig in and tell the story again.

But Sidles still relied on the VA for medical care. He needed knee surgery and had been prescribed medications for depression, sleep, and pain in his shoulder, knee, and hips from military and sports injuries. A VA doctor advised him to quit climbing or he risked needing hip replacements. Sidles figured he’d be better off with his own therapy regimen—smoking weed and climbing.

On a fall day in 2014, he called the VA’s outpatient clinic and was soon yelling at a nurse about an upcoming appointment. Patricia Alexander, the clinic’s supervisor of mental-health services, took the phone. “We couldn’t sort through the obscenities,” she told me. “I got tired of it and hung up.” An hour later, Sidles was sitting in the clinic. Alexander, five feet tall and 100 pounds, stood in front of him. “Hi, I’m Dr. Alexander. How can I help you?”

“I want to talk to the motherfucker who hung up on me,” Sidles said.

“I would be that motherfucker,” Alexander said. “How can I help you?”

The response threw him off, and calmed him. They went to her office to talk, the first of what would be six visits in all. They established something of a pattern in their relationship, with Sidles testing and Alexander pushing back but not rejecting. “I could just pick you up and snap your neck, and there’s nothing you could do about it,” he told her in a session a few weeks later.

“Yeah, but could you wait?” Alexander said. “I just got custom ski boots and I’d like to use them.”

Sidles laughed at this and relaxed.

“I never felt I was in danger from him,” Alexander said. “Never once, even when he was raging.” The clinic director, Kris Johnson, who served eight years as an Army doctor, told me he interpreted Sidles’s comment more as a statement of frustration than a threat. “I’ve seen so many people like that. They’re pissed at the world, not you specifically,” Johnson said. “At some point they give up. This is just some other fucking VA doc who doesn’t know what he’s talking about.”

The VA had previously diagnosed Sidles with borderline personality disorder, characterized by impulsive behaviors, extreme emotional responses, and unstable relationships. The military considers this a preexisting condition, not service related—war didn’t break them, they were screwed up already—and has used the diagnosis to discharge service members and deny disability benefits to thousands of combat veterans. “Someone who didn’t know what they were doing gave him that diagnosis,” Alexander said. “I got that overturned. Dan had untreated PTSD.” She also got Sidles’s PTSD disability rating bumped up to 100 percent.

In Alexander, a former Air Force and Army psychologist, Sidles had a passionate advocate. Her youngest son had served a violent tour in Afghanistan as an Army paratrooper, and afterward he boozed and fought. Alexander told me that a therapist at the Denver VA identified his PTSD symptoms but did little to alleviate them. Alexander could sense her son’s mounting hopelessness and devised her own treatment regimen, outside VA channels, including , yoga, , and . “Without it,” she said, “I think he would be dead.”

She thought Sidles was headed down the same path and figured he could be helped by a similarly tailored intervention. Alexander recognized the importance of addressing Sidles’s childhood, which she said is too often overlooked within the VA. Many providers don’t understand or appreciate how early trauma compounds war trauma, or they’re hamstrung by the handful of treatments they can offer.

The first few sessions with Sidles were triage. Alexander sketched a human brain and explained to him how traumatic memories are stored and the neurological effects of too much stress. She wanted to get Sidles a brain scan, to show him how PTSD and his injuries had altered his neurological function, influencing behaviors.

Adrenaline, a critical component of our fight-or-flight response, heightens our senses, dulls pain, and curbs our need for food and sleep. It’s designed for short bursts. But if the brain is chronically stressed—by childhood abuse, combat, or a toxic mix of the two—adrenaline stays high, masking the commensurate drop-off in other brain chemicals that regulate emotions and sleep. Boxing and climbing the Flatirons without a rope offered a little shot of adrenaline, a fix to calm the mind and body. “He was raised on fight-or-flight, so he was going to be drawn to things that would push that adrenaline up. Fighting. Screaming. Thrill seeking,” Alexander said. “He was trying to manage that incredible imbalance in his system. Then you add traumatic memories and losses, and no one explains it to you, you’re going to get hopeless real fast.”

To help Sidles, she needed to regulate that roller coaster of hormones. “What could we do to calm your brain down?” she asked him.

Skiing, he said.

He didn’t have the equipment, or money for a ski pass, so Alexander worked on getting him both. Others at the VA told her to stop because it wasn’t an appropriate treatment, Alexander said. She refused, and Sidles eventually obtained equipment through , a nonprofit supporting veterans. “It was a totally appropriate treatment,” she told me. “He needed to be outside.” Sidles got the skis, but their next meeting was their last.

“How’s it going?” Alexander asked as they sat down in her office, and that set him off. He yelled and pounded on a metal bookshelf. Other staff heard the commotion and stepped into the hallway. Someone called the police, and Sidles left. Johnson and Alexander wanted to continue seeing him, but others at the clinic felt unsafe. The VA’s disruptive-behavior committee in Denver, which reviews the cases of veterans who may be a threat to staff or other patients, banned Sidles from the Golden clinic and said he would need a police escort at the Denver VA. Sidles thought it was Alexander who had banned him. Another person he trusted had let him down.

“If we could have kept him here, I think we could have made a difference in his life,” Alexander said.

In 35 years as a psychologist, and many years working with combat veterans, Alexander has had many clients kill themselves. But she thinks most often about Sidles. “I feel like we failed him,” she said. “We’re losing a generation, and I can’t stand it anymore. We’re not doing our job.” Alexander retired from the VA last December and has joined a Denver-based nonprofit, , which will offer veterans the kind of treatments that helped her son—treatments she feels could have helped Sidles.

The VA has made suicide prevention its top priority, this year allotting $500 million to pay and resources. But even if the VA filled every job vacancy, the fix assumes that doctors and therapists are providing the right care at the right time to the right people. As Sidles’s case shows, that isn’t always so.

“We give it our best guess, and then we start throwing medication at people,” Alexander said. “People lose hope and become suicidal when they can’t fix it and they don’t know why.”

Over the course of several months of talking with people about Sidles for this story, I had become increasingly discouraged; so many told me that they had been aware of his struggles but had felt helpless to stop the slide. If nothing could have been done, digging into his life felt grotesquely voyeuristic. But Alexander and Johnson helped me understand two critical pieces of Sidles’s story: his path was not inevitable, and he was not an exception. His actions may have seemed extreme to those with a frame of reference based on a better childhood and more conventional adult experiences. But Alexander and Johnson found his story far too familiar.

Several combat veterans expressed the same thing to me. “A lot of people look at Dan like he was some fucked-up outlier,” Brandon said. “No. He could be any one of us.” Good treatment was critical for Brandon, but so was community, and Sidles’s increasing isolation left him without that.

“The community piece is huge,” Brandon said. “Loneliness is a fucking killer.”

Kremmling, Colorado, sits on a high plain 100 miles northwest of Denver. The old mining and ranching town of 1,500 doesn’t have much charm, but it’s cheap and well situated for climbing and skiing in the surrounding mountains. Another try at a fresh start.

In December of 2015, after briefly moving back into Murray’s place in Boulder, Sidles relocated to the Kremmling Apartments, a two-story building in the center of town with a couple dozen units. He was glad to be away from the Front Range congestion and from Boulder, where he felt out of place. But this put him far from what remained of his support network. His physical remove mirrored his growing emotional isolation.

If he wasn’t out climbing or skiing, Sidles was often at , a mixed-martial-arts gym in Granby. He worked out alone, pounding the bags, sweat pooling on the floor. At home he’d drink beer, maybe smoke some weed, play guitar.

Kremmling isn’t very welcoming to strangers, and neither was Sidles. A confrontation, whether just likely or inevitable, occurred on the evening of February 4 outside his apartment. Sidles said it wasn’t his fault; the police disagreed. He had yelled at a woman as she smoked a cigarette outside her apartment, accusing her of messing with his car. The woman’s brother heard the commotion and approached Sidles, who knocked him down with a punch that broke a tooth.

The police charged him with third-degree assault and disorderly conduct. A Breathalyzer test said he was plenty drunk. Deputy Jesse Stradley, the sheriff’s department’s veteran-liaison officer, served in the Navy and worked at the jail. He first met Sidles the night of his arrest. “I told him not to come toward me,” Sidles told Stradley, referring to the fight. “Why would a guy pet a barking dog?”

A barking dog. A tiger on a chain. A disposable razor. Sidles saw himself in many ways, few of them good.

Sidles was released the next night on $1,500 bail and assigned a court date the following month. He and Stradley met again by chance a few days later. After that they got together at least once a week for lunch or a workout. Sidles called or texted him most days, often to vent his frustrations about his landlady, how old he felt, or how people didn’t understand him.

He also reached out to Duane Dailey. As a medic and surgery tech in Vietnam, Dailey had repaired soldiers’ bodies; as the veterans service officer for Grand County, he helped them repair their lives, connecting them with VA programs, medical benefits, and employment. In March, Sidles asked Dailey for a ride to pick up his car at the mechanic. “Why are you living in Kremmling?” Dailey asked as they drove. “It’s a sucky town unless you’re a cowboy or you love to fight.”

Close to the mountains, Sidles said.

As he did after all his veteran interactions, Dailey jotted down brief notes about his phone calls and meetings with Sidles.

March 7—He wanted to be in a small town to get away from the bullshit.… No one understands. He’s very lonely and has no friends. Needs meds for depression. He informed me he understands why so many vets kill themselves.

March 18—Dan is very depressed, despondent, paranoid.

Sidles appeared in court on March 21, and the case was continued to May 2. Dailey found Sidles a cheap apartment in the nearby town of Parshall and helped him move some belongings into a storage unit, preparations for Sidles’s new plan: an eventual move to Thailand, where a Marine buddy owned a mixed-martial-arts gym.

A confrontation occurred on the evening of February 4. Sidles said it wasn't his fault; the police disagreed. He had yelled at a woman as she smoked a cigarette outside her apartment, accusing her of messing with his car. The woman's brother heard the commotion and approached Sidles, who knocked him down with a punch that broke a tooth.

“I’d like to go out with a girl and just talk to her, be like a normal person,” he told Dailey as they drove. “That doesn’t work. I can’t do it.”

At the storage unit, Sidles beat his fists against the door and wept.

“Dan,” Dailey said, “we need to get you some help.”

Dailey reached out to a friend, Kris Johnson, who told Dailey he already knew Sidles from the Golden clinic. Johnson planned to be in Kremmling later that month for a town-hall meeting on veterans’ benefits. If Sidles wouldn’t attend, he and Dailey would stop by his apartment to see him.

But that was three weeks off, and the pressure was building. With a court date looming, Sidles oscillated between pragmatism and despair.

“Totally serious, can you work out in jail?” he texted to Stradley. “Do you get to bring books, etc?”

Stradley told Sidles that jail time in Grand County would be easy. The food was good, the atmosphere relaxed. He could read books and do body-weight workouts.

The assault charge carried a maximum sentence of two years in jail and a $5,000 fine. Someone with no criminal record might not get any jail time, but Sidles was looking at 30 days and a bill for the man’s broken tooth. Brett Barkey, the district attorney for Grand County, felt jail might be good for Sidles. “Sometimes that’s enough to encourage them to take a different path,” he said.

Dailey disagreed. “He’s like a caged animal now,” he said. “If you put him in a real cage, it will make it worse.”

Barkey, a retired Marine colonel, served three tours in Iraq. That he had worn the same uniform and still wanted him locked up felt like another betrayal to Sidles.

“For him to expect to get a pass because I’m a Marine is misplaced,” Barkey told me. “Folks who aren’t held to account end up exhibiting these behaviors that are counterproductive and dangerous. I’m not going to be an enabler.”

Many of those who pushed back against Sidles found themselves cut out of his life. But the arrest thrust Sidles into a realm he couldn’t simply turn his back on.

April 11—Vet has no friends. No one cares about him. He will kill himself if he has to go to jail. He’ll break the neck of man who he assaulted. He understands why so many vets kill themselves.

While awaiting his court date, Sidles stewed in Parshall, a has-been town with a couple of bars and a few dozen people. The apartment building wasn’t much: a long, single-story cinder-block building next to the post office, divided into five units. Sidles had two small rooms and a walk-through bathroom, furnished with a bed, a small table, and a couch, for $500 a month.

He told Dailey he was happy with the new apartment, away from gawking neighbors in Kremmling, but within days he complained to Stradley about the isolation, neighbors slamming doors, and spotty cell phone service.

As Sidles spiraled, Chad Jukes, another veteran from our 2010 Nepal climb, was back in the Khumbu Valley, headed toward Mount Everest. In Iraq, a roadside bomb had damaged his right leg, which was later amputated below the knee. Like Sidles, Jukes had climbed all over the world. He’d gained a few gear sponsorships, often spoke to groups about his experiences, and taught ice climbing—a life Sidles had imagined for himself. The Nepal trip had seemed like a launching pad for Sidles as well, but almost six years on, the two men couldn’t have been in more different places or states of mind.

On April 3, Sidles posted a Facebook link to a story about a bid by Jukes and another veteran to become the first combat amputees to summit Everest—which Jukes would do on May 24, , veteran reintegration, and suicide. Above the link Sidles wrote: “All you I fought with in Fallujah, this is a real hero.” He didn’t mean it as a compliment; Jukes was wounded running convoys in Iraq, not kicking down doors and hunting insurgents. Sidles found the distinction extreme. “If you want to be inspired by this ‘look at me fuck’ I’ve seen guts this girl doesn’t have,” he wrote in the comments.

In one of his last Facebook posts, dated April 22, Sidles shared a link about an Army veteran who had killed herself. “I’m sorry life didn’t work out the way you deserved,” Sidles wrote. “If there’s an afterlife, protect us. We’ll see you soon.”

He left Dailey a voice mail on April 26, telling him that he was depressed. Dailey called him the next day, but Sidles didn’t answer.

The following day, Dailey brought a local Marine veteran to visit him. Sidles’s gray Toyota FJ Cruiser was parked outside. They knocked; no answer. Dailey could guess where this was headed. He had had one other suicide, a few years earlier. Police found the veteran in his car along a remote road, dead from a shotgun blast, with Dailey’s card in his pocket. On the back, the Marine had written “My only friend.”

Stradley was worried as well. He hadn’t heard from Sidles since a text on April 25. “He said to me once that he’s not going to make it,” Stradley told me. “It was sickening to me, because I didn’t know how to help.” Sidles told him that just having someone to talk to, someone to listen, had been a great help. “I considered him a friend, and I told him that,” he said. “You don’t push a person if they don’t want to be pushed. I didn’t want him to delete me as a friend. Being up here, you need somebody.”

The day after Dailey’s visit, Stradley called his boss, who dispatched deputies for a welfare check.

They found him in the bedroom.

Sidles, who so often climbed without a rope, without that umbilical to keep himself anchored to the earth, to save himself should he fall, had ended his life with a tether. He unlaced his boxing gloves and looped a noose around his neck, and in his small closet he tied the other end to a bar on the back wall, about four feet off the ground. This was not a quick or inevitable death, with agency withdrawn and the course set after an initial action: a trigger pull, a step off a bridge, a leap from a rock face.

Instead, Sidles fought. He fought against himself, against the world, until his very last moment. With his feet propped against the wall, Sidles pushed. He pushed so hard that the bar bent nearly into a U.

They found him on a Friday, and by Monday, news of his death had migrated to Facebook. Messages flooded his page. Grief and shock, but anger, too.

“Dude we talked two weeks ago about all this shit going on in your life and when I asked you if you were good you said yes. So you lied to me which is why I’m disappointed. I’m angry with myself for not flying up there and making your ass come home with me.”

“I’m pissed that you bitched out on the rest of us and now there’s one more brother I have to let go of. We’re all hurting inside from the past that haunts us and the memories that can never be forgotten But I’m going to walk this one out until my days are ended but not by my own hand.”

“One of the baddest motherfuckers that ever set foot on Gods green Earth… I’m fucking heartbroken.”

Tami McVay, who served in the Marines and dated Sidles briefly after our Nepal trip, had been doing a push-up challenge popular on Facebook—22 push-ups a day for 22 days, to raise awareness about veteran suicide. “About midway through, I shared a little bit about Dan in a post. I said, ‘My friend has gotten into mountaineering, he’s doing really well,’ ” McVay recalled. “And then three days later this happened.”

Sidles left a note. Gilderhus hasn’t let anyone read it, but she told me some of it: “I tried to get help, and this is what happened. I’m sorry for hurting everybody, especially the ones I love.” He also figured not many people would care about his passing. “There will only be a few people at my funeral, maybe 20,” he wrote.

He was wrong about that. Dailey and Stradley spent a few days organizing a memorial, and on May 5, . Climbers crowded next to local veterans and law-enforcement officers. More than 30 Marines who served with Sidles gathered from across the country. Several had been in touch over the years; others hadn’t seen Sidles, or each other, in a decade.

A bagpiper played the “Marines’ Hymn” and the American Legion honor guard fired a three-volley salute. Led by the Marines, everyone filed past the table and laid a hand on the box that held Sidles’s remains. In the minds of many people at the memorial, his was a combat death, the same as if he had fallen in Fallujah.

His Marine buddies gathered that afternoon in a pub down the road. They drank and laughed and traded stories about Sidles, about the war, and about everything afterward. Some military units have been stalked by suicides, but Sidles’s was the first for his company. The Marines implored each other: Reach out. Don’t let this happen again.

For the next two years, Sidles’s friends would carry him around the world, to the places most meaningful to him. A cousin who is also a Marine spread some of his ashes this spring on a memorial hill at , in California, where Sidles had been stationed, and Gilderhus is coordinating with to have some of his remains interred there, which she expects to happen this fall.

Last fall, Kevin Noe, who climbed with Sidles in Colorado and on Aconcagua, spread some ashes on Lobuche, where Sidles’s life in the mountains had begun. A few months before that, Noe and I tucked a bottle with ashes into a backpack and headed for Mount Elbrus in southeastern Russia for our own unfinished business.

On our first Elbrus attempt, in 2012, Noe and I climbed with Sidles, Murray, and Steve Baskis, who had been blinded by a roadside bomb and had been with us in Nepal. Halfway to the summit, still two hours before dawn, Murray fell ill. He tried to continue but didn’t have the energy. He said he could turn back alone, but we quashed that. In the dark, with one blind and one sick climber, we figured it was safer to move as a group. Sidles felt strong, and we encouraged him to continue with the other climbers—a Russian woman and two Chinese with a Russian guide. We wished him luck, and the beam of his headlamp faded as he trudged higher up the mountain.

As we headed down, a spitting snow rose into a swirling, howling whiteout. We lost our way and veered far off the route. After dawn, during a brief break in the snow and clouds, we could see base camp a half-mile away. We started for it and walked into a vast crevasse field obscured by a layer of fresh snow. With a thunderstorm parked overhead and charging the air, we roped up and picked our way through the field. Noe walked point, poking a trekking pole into the snow to search out solid ground. Hours later, exhausted, we staggered back into camp.

Sidles fared better. The Chinese climbers turned back with their guide an hour after we had turned back, but the Russian woman climbing with Sidles said she’d been to the summit before and that they should continue. They climbed on, with daylight bringing only slightly better visibility. In the clouds and the snow, they could just make out the sporadic wands along the route. A summit marker and small shrine told them they had reached the top of Europe.

Now we walked the path Sidles had taken five years earlier, across the broad saddle between the two summits and onto the slopes of the higher peak. The wind dropped to a mild breeze, and the rising sun warmed us.

We stepped onto the summit under a clear sky, mountains stretching to the horizon. I thought of Sidles standing here in the clouds and the snow, never seeing the world spread out before us now. And I thought of the chaplain’s blessing on the grassy, windy hilltop in Colorado. “It seems fitting that we should leave our comrade to rest under the arching sky, as he did when he pitched his tent, or laid down in days gone by, weary and footsore,” he’d said. “May each of us, when our voyages and battles of life are over, find a welcome in that region of the blessed, where there is no more storm-tossed sea or scorching battlefield.”

Every moment, every choice, for the living and the dead alike, had led us here.

Noe tipped the small bottle, and the ashes poured out, pale gray on a field of white.

Contributing editor �������������Ѵdz����Գܱ�� wrote about nature therapy for prison inmates in September 2016.