The Ghost Trail Hunters of Mount Desert Island

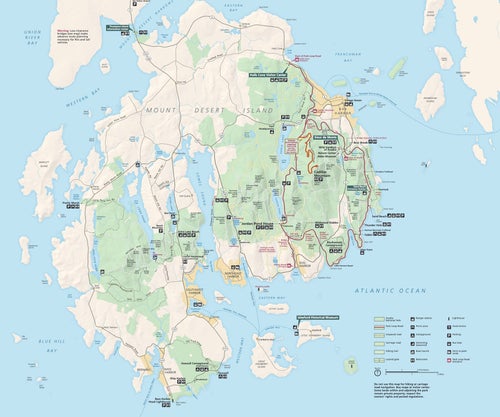

Acadia National Park in Maine boasts 150 miles of trails on its official maps, but that’s only a part of what once existed. Matthew Sherrill tagged along with a couple of local history obsessives to explore some of the dozens of unmarked paths that lead to what were once major attractions—places some want to stay a secret.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On a cloudless spring day in mid-May, I pulled into an overlook of no particular significance off the loop road that runs through Maine’s Acadia National Park. An informational placard provided tourists with a boilerplate account of a 1947 wildfire , but the site’s chief distinction was the pleasant, if unexceptional, view of Dorr and Cadillac, two of Acadia’s tallest mountains. As I maneuvered into a parking space, another motorist had his camera aimed at the peaks and was furiously snapping pictures. Beside me in the passenger seat was Matt Marchon, the 37-year-old author of a self-published two-volume work called . And fittingly, we had come to the overlook that day not to marvel at the view or learn about midcentury wildfires, but to hike an abandoned trail to a forgotten place.

We waited for a park ranger to vacate the turnout, then crossed the road and scrambled over a granite ledge, where we found an unmarked but well-trodden footpath that wound up the hillside. As we began to stroll out of sight, the tourist in the turnout gazed up at us, looking confused, a hint of suspicion in his eye, as though we knew something he didn’t—which, in truth, we did.

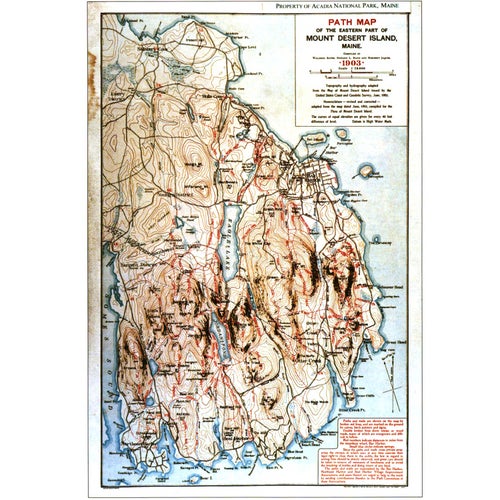

The trail, Marchon told me, led to a modest 640-foot prominence called Great Hill. When he was a kid, his parents used to pull over here frequently, and he always had a hunch that something interesting lay above that shelf of granite. “It turns out I was right,” he said proudly. As an adult, Marchon read a blog post about an old unmaintained trail leading to Great Hill and realized that it began above that very same rock shelf. But while the site is clearly labeled on most contemporary hiking maps of the region, no trails are shown leading to its summit. Look at , however, and Great Hill appears to be a major attraction, with no fewer than three separate trails leading up its slopes.