This year IÔÇÖm planning╠ř29╠řguided backpacking trips. They are scheduled through October, run three to seven days, and are scattered throughout North America in the high desert, eastern woodlands, Mountain West, and Alaska. I will also ready my companyÔÇÖs more than 240╠řclients, who are of mixed ages, genders, fitness levels, and experience.

To pull this off efficiently and minimize mistakes, over the years IÔÇÖve developed a planning process╠řthat works╠řfor any trip and can be used by any backpacker.

1. Define Your TripÔÇÖs Parameters

General questions are╠řa good starting point for trip planning. You╠řdonÔÇÖt need definitive answers to every question right away, but youÔÇÖll want to begin╠řnarrowing your options.

Start by╠řasking where you want to go,╠řwhen, and what╠řkind of trip it will be. rather than car camping?

Then╠řadd more specifics. What length of time will you be traveling? What specific trails, routes, landmarks, or campsites do you want to visit? How many miles or how much vertical distance do you intend╠řto cover? Who else do you want to join you, if anyone?

Finally, consider the logistics. Do you╠řneed permits? If so, how, when, and where will you get them? How will you╠řget to the trailhead╠řand back? Are there unique or notable land-use regulations or requirements you need to be aware of?

I suggest╠řtaking all these details and dropping them into a╠řdocument that╠řcan be shared with emergency contacts before you╠řleave.

2. Research Conditions

Once you have a reasonably defined trip plan, research╠řthe conditions you╠řwill likely encounter, so that you can prepare properly, mitigate risks, and rule out baseless what-if╠řscenarios.

IÔÇÖm only interested in or╠řdemand particular skills. I recommend looking into╠řclimate, sun exposure and hours of daylight, footing (the most common types of walking surfaces), vegetation, wildlife and insects,╠řnavigational aids (signage, blazes, cairns, and posts), water availability, remoteness, and potential natural hazards╠řlike avalanches and lingering snowfields, river fords, possible flash floods or tides, or lightning.

Compile the findings of your research in a separate document, and cite your sources, so you╠řcan easily compare any contradictory information you later find elsewhere.

3. Select Gear

For a beginner backpacker, the task of gear selection is usually the most time-consuming, certainly the most expensive, and unfortunately also the most frustratingÔÇöitÔÇÖs very easy to go down the rabbit hole here. A good and run-down of gear is a great place to start.

To make this process easier for my clients, I give them a╠řtime-tested╠ř╠řthat I designed, along with examples of╠ř╠řfor trips similar to the one theyÔÇÖre going to take╠řand a╠řcopy of╠ř. These resources should help cut through the noise.

Clients also have email access to their guides and their group, so that they can get trip-specific advice. If you donÔÇÖt have an immediate contact who really knows their stuff, I suggest a community forum like RedditÔÇÖs╠ř. Make sure to tailor your gear to your itinerary and expected conditions.

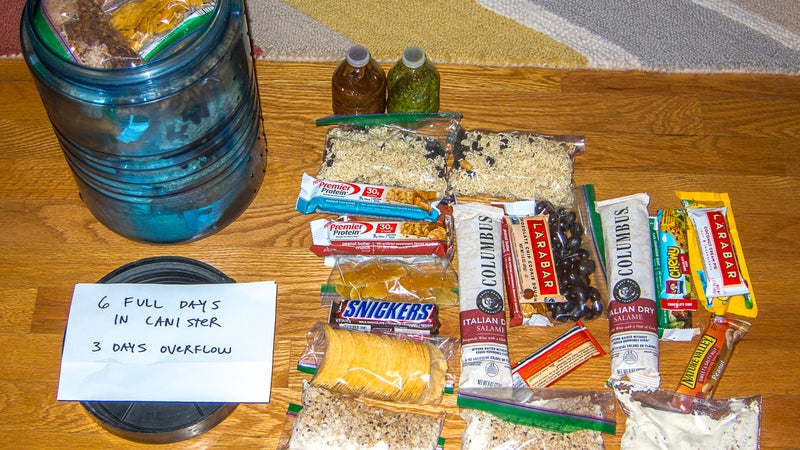

4. Plan Your Food

WeÔÇÖre vulnerable to packing our fears.╠řIf we fear╠řbeing cold at night, we bring a sleeping bag thatÔÇÖs excessively warm. If we fear bears, we sleep in a full-sided tent (which wonÔÇÖt help but may make us feel better). And if we fear being hungry, we pack too much food.

IÔÇÖve given in-depth meal-planning recommendations before, so here IÔÇÖll just go over some basic pointers. First, plan to consume╠ř2,250 to 2,750 calories per day. (I generally assume╠řan average caloric density╠řof 125 calories per ounce, which means about 18 to 22 ounces daily.)╠řIf youÔÇÖre older, female, petite, or on a low-intensity trip, go with the low end of this range. If any of the opposites are╠řtrue, go with the high end. Variety is the spice of life, so pack foods with varying tastes (spicy, sweet, salty, sour) and textures (chewy, crunchy). Early in a trip, treat yourself with real food, like a ham sandwich, an avocado, or an apple. This╠řwill also delay╠řthe onset of culinary boredom.

For breakfasts and dinners, try these╠řfield-tested options╠řinstead of spending your hard-earned cash on exorbitantly priced freeze-dried meals or punishing yourself with thru-hiker fare like ramen noodles or Lipton Sides.

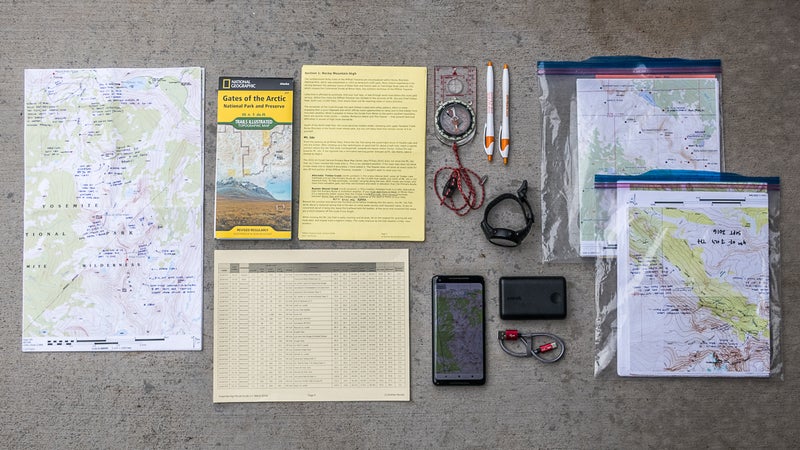

5. Create or Collect Navigational Resources

For my first hikes, I utilized whichever resources were conveniently available and seemed sufficient. Before thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail in 2002, for example, I purchased the ╠řand downloaded╠řthe Appalachian Long Distance Hikers AssociationÔÇÖs╠ř. To explore ColoradoÔÇÖs Front Range the following summer, I bought a few National Geographic Trails Illustrated maps that covered the area.

But when I started adventuring off the beaten path, I had to create some or all of these materials from scratch. Through this process, I developed what I believe to be an╠řoptimal system of maps and resources╠řthat includes large- and small-scale╠řpaper topographic maps, digital maps downloaded to a GPS app, route descriptions and tips, and a╠řdata sheet (a list of key landmarks and distances along a trail or route).

6. Gain Fitness and Skills

ThereÔÇÖs no better way to improve your hiking fitness than by hiking, and thereÔÇÖs no better way to develop backpacking skills than by backpacking.

But who has the time and ability to do that? Not me, and likely╠řnot you.

The next-best option is to work out more intensely╠řto maximize the potential of the time you do have available. Personally, I╠řdo this by running╠ř60 to 70 miles per week. Ultralight backpacking pro Alan Dixon has a╠ř╠řthatÔÇÖs more hiking oriented (and╠řmore realistic). You can also read and watch skill tutorials, such as my series on╠řnavigation,╠ř,╠ř,╠ř, and╠ř.

A test hike╠řis also very valuable. This systems check╠řis meant to be done in a relatively low-risk╠řenvironment, and the goal is to get you better prepared for your actual trip. It can be done locally, like in a nearby park or even your backyard,╠řand╠řwill give you an opportunity to use your gear, practice some skills, and identify room for improvement before you undertake a more committed╠řitinerary. Focus on╠řreplicating╠řthe elements of a real trip: hike with a loaded pack, refill your water bottles, change layers, set up your shelter, cook a meal, etc.

7. Conduct a Final Check

In the days before your trip, complete any remaining housekeeping. Using your checklist, pack up all your gear, including your maps, resources, and permits. Buy any necessary perishable foods, like cheese, butter, and tortillas. (This╠ř╠řhas more details.) Look at a five-day weather forecast, and adjust your gear accordingly. Finally, proofread╠řyour trip-planner document, and leave it with your emergency contacts.