Everyone told Tom Kennedy to expect flooded trails when he hiked through in the spring of 2015. But as he sloshed��through miles of waist-deep swamp water that hid��alligators and aggressive snakes, the trail quickly got the better of him.

Right from the start, at the Oasis Visitor Center, in the middle of Florida’s southern tip, the trail disappeared into a sawgrass swamp, the wispy green stalks climbing above Kennedy’s head. He waded in and soon found himself struggling for every step through muck that was as thick as drying concrete��and��threatening��to pull off his boots. With��little dry land available, he made camp in a hammock.

This was Kennedy’s second-ever long-distance hike. He had done the first one, a��journey up the��Appalachian Trail, way back in 1980. After getting laid off from his job selling mattresses in 2014 and well into his sixties, he decided to tackle another of the nation’s designated scenic trails. He picked the 1,300-mile Florida National Scenic Trail because, with a top elevation of just 300 feet,��it sounded relatively easy.

On day three, after 30 miles of mostly sodden trails, Kennedy finally made it through to the other side of the million-acre Big Cypress swamp. He was��so thoroughly dehydrated that he could barely speak.

As Kennedy emerged, a character that seemed straight out of fiction stood in front of him. The man looked like Don Quixote, his mustache jutting out like steer horns on the front of a Cadillac. He introduced himself as Nimblewill Nomad, a legend among long-distance hikers who set out in 1998 to finish the Florida Trail and didn’t stop��walking until he got to Quebec. Since then, the Nomad, whose real name is M.J. “Sunny” Eberhart, finished tens of thousands of trail miles. “Now, this is a man who had his toenails surgically removed so they wouldn’t fall off,” Kennedy says.

The Nomad eyed him up and down. Kennedy looked like Chevy Chase after getting lost in the desert in Vacation. It was downright comical—until you got to his feet. He had stripped off his boots and muddy socks, and his feet were black and covered in blisters. A section of his right heel looked as if it had been scooped out by a melon baller. “In all my years on the trails,” the Nomad told Kennedy, “I’ve never seen feet that bad.”

For those who have hiked the Florida Trail, running into find-them-nowhere-else characters and nearly impossible obstacles is part of the charm.

Like the state it occupies, the�� maintains a reputation for its surprising difficulty and eccentricities—the hiking version of the oddball “”��made famous on Twitter and in late-night monologues. For those who have hiked it, running into find-them-nowhere-else characters and nearly impossible obstacles is part of the charm.

The entire path is about the same distance as a walk from Canada to Mexico. While a few thousand people register every year to hike the length of the Appalachian Trail and other well-known routes, this one averages about 30. “The Florida Trail is like the ugly stepchild,” Kennedy says. “It gets the least amount of attention, yet it is the toughest trail out there.”

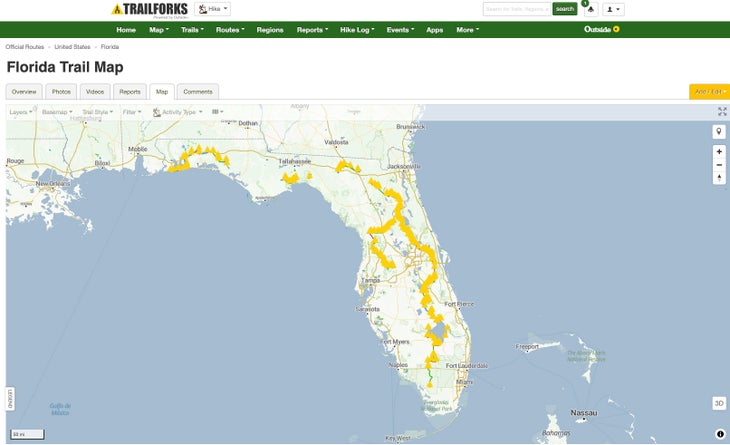

That’s thanks in part to the swamp water. Most hikers begin in the south, in Big Cypress, the no-man’s-land between Naples and Miami, so they’ll��finish the hottest section first. Flooding often devours large swaths of the trail in the 150 miles between Lake Okeechobee and Ocala National Forest in central Florida. Then��hikers will almost certainly have to wade through more��water again before reaching the northern terminus in , south of Tallahassee.

The muck soaks backpacks and drowns campsites, leaving hikers little choice but to continue in wet shoes and socks. Bears, panthers, countless alligators, and aggressive water moccasins share the same swamp water��that floods the trail.

Jane Hamilton,��a trail angel��who helps hikers along the way and volunteers to maintain a stretch of the trail northeast of Gainesville, acknowledges the rampant rumors about another creature hikers��might face once they get up to the Panhandle. It’s a legend she says was created by one of the trail volunteers years ago, a little “joke about the sasquatch.” Most people call it the Skunk Ape, and believers say the creature uses the Florida Trail as a hunting path. There’s even a tourist trap called the Skunk Ape Research Headquarters��near the trail’s southern end.

Hunters populate the woods, pursuing deer from late summer through much of winter and wild boar all year. Although regulars say there have never been hunting-related accidents, bringing a blaze orange vest isn’t a bad idea.

Then��there are the unfinished sections that send hikers onto roads and highways through Orlando’s��suburbia. That route, cutting through the center of the state, got its rough design after a Miami real estate agent��named Jim Kern took his family on a 40-mile hike of the Appalachian Trail in North Carolina in 1966. He returned to Florida and set out to create��a Sunshine State version. In his mid-eighties now, Kern is still fighting to complete the final sections, about 300 miles, which he guesses will cost another $200 million.

Even in its incomplete state, the Florida Trail is one of just 11 federally designated national scenic trails, and while few walk its full length, the trail��attracts more than 350,000 people each��year��who bite off sections.����for day hikers include the quartz-white sands in Gulf Islands National Seashore and the forests of skinny pines that jut up like toothpicks in Ocala National Forest.

Thru-hikers are a rare sight, so much so that locals often mistake��them as homeless, says Alex Stigliano, program director at the , a nonprofit that maintains the trail and has 4,000 members. He was recently explaining thru-hiking��to a sheriff in��a rural Florida county, and the man interrupted Stigliano to ask, “Hold on a second. You’re telling me people don’t have jobs and just go hiking for a couple months?”

Sandra Friend first walked the length of the Florida Trail��back in 1999, after hearing about it from Eberhart a year earlier at an Appalachian Trail gathering. After finishing the Florida Trail, she found herself captivated by it and began publishing a well-used guidebook in 2002. Friend met her husband, John, on the trail in 2011, and they teamed up in 2015 to create the that has��become popular among hikers.

Large sections remain unused except for the handful of people making��the full-length trek, Friend��says, so the Florida Trail has developed a reputation for eccentrics. “There are oddball people attracted to long-distance hiking. It’s a vortex for it,” she says. “I’ve met some bizarre people along the way. But they’re harmless—just different.”

In 2014, when Stigliano first moved from Maine to Tallahassee, he asked his boss if he should buy a gun before setting off on the Florida Trail. “He said, ‘Oh, god,��no.��Actually, please don’t do that,’” Stigliano recalls. “When you hike the trail, you don’t see a lot of other people, and when you do, it’s like, ‘Oh, cool, hey.’”

Janie Hamilton is another trail angel who maintains a section northeast of Gainesville. She often agrees to shuttle hikers who want to skip portions of feet-punishing paved roads. Sometimes those drives mean hours getting to know complete strangers who just wandered out of the woods. “You meet the neatest people,” Hamilton says.

It’s common for those who have spent time on the Florida Trail to walk away with stories you wouldn’t expect to happen elsewhere. Those hiking��the trail recently��might have met Kyle “The Mayor” Rohrig, who completed 1,100 miles with his blind Shiba Inu, Katana, riding on his shoulders. You might have also found herbalist Heather Housekeeper, who collects edibles like yellow dandelion flowers to cook in crepes.

However, the trail’s reputation for eccentrics, Eberhart says, is not something that should frighten away first-timers. “You might see these people on the trail who will make you want to walk across the street to avoid them, but once you get to know them, they will become your new best friend,” Eberhart��says.

Since retiring from his job as an eye doctor in Titusville, Florida, in 1993, Eberhart,��the Nimblewill Nomad, says he slowly reinvented himself.��He once had an office where he showed up and left at the same time every day and looked the part of a physician. After retirement, he let his sugar-white hair grow to his shoulders and��his beard fall to his chest.��He replaced��his schedule with mostly unplanned travel, tacking on new trails to the ends of other hikes just because he felt like walking some more.��Eberhart admits one reason he always finds friends among Florida Trail hikers is that he’s found a place where he fits in. “I’m one of them,” he says. “Maybe that makes it easier for me.”

The trail certainly has a reputation for interesting characters, but there’s another reason Andy Niekamp would be wary about recommending it. An accomplished long-distance hiker from Dayton, Ohio, Niekamp set off on the Florida Trail on December��16. He had already completed a half-dozen major hikes, including the Appalachian Trail four times. He also runs , a company that leads people on backpacking trips. But��the Florida Trail is simply too harsh, too unforgiving for anyone but the most serious of backpackers. “Well, I would probably not take clients down to do that,” Niekamp says.

During Niekamp’s journey, controlled burns reduced entire sections of the trail to black ash, obliterating markings and leaving him to find his way using GPS. His shoes never really dried out during��the entire length, and coarse muck between his toes meant he was always in danger of abrasions and the infections swamp water might carry. In the swamps, he used a walking stick in an attempt to shoo away alligators and water moccasins. Niekamp��finished on February��26, 2019—a journey of more than two months.

James Rieker and Ryan Edwards Crowder, two twentysomethings who set out to hike the entire Florida trail in December 2017,��lost the trail markers while wading in waist-deep water not long after starting their hike.��They went four days without food and water until they could finally get a cellphone signal. Deputies hoisted them out of Big Cypress by helicopter.

Things didn’t turn out as well at the end of the hike for Nick Horton and Logan Buehler, who work together at a Fort Lauderdale company that helps addicts find a rehab clinic. Horton says they were unprepared when they set off on July 23, 2018,��for a 15-mile hike on a stretch north of Alligator Alley, the highway that bisects the southern tip of the state. They brought nearly a gallon of water each but quickly ran out. When they found the trail flooded after about eight miles, they decided to continue, but dragging their feet through the muck took hours longer than they predicted.

It wasn’t that Horton was an inexperienced hiker. Growing up in Arkansas, he and his��parents went into the woods nearly every weekend. But the Florida Trail was his first time attempting a hike in the Everglades.

Ten miles in, Horton and Buehler came to Camp Noble, where they noticed just one lone tent. The sun had begun to set. It took Horton’s eyes a moment to adjust to the dim light within the tent. Inside was an emaciated figure, so skinny he looked like a caveman. He was dead, still sitting cross-legged, eyes wide open and staring straight ahead.

The Collier County Sheriff’s Office is still trying to identify the man in the tent. The best anyone can determine is that he went by the trail names Denim and Mostly Harmless. It was days before Horton stopped seeing the man’s image when he closed his eyes, and now he’s just glad it wasn’t him. “We knew we bit off more than we could chew,” Horton says.

Difficulties of the trail aside, Niekamp admits that the country’s only subtropical trail surprised him with its beauty. In the south Florida swamps, he waded between prehistoric-looking strands of cypress trees that rise like ancient stone statues. On pathways of sugar sand north of Lake Okeechobee, he marveled at live oaks with limbs that could cover a city block and��Spanish moss drooping like a graying beard. In the Panhandle, he passed between spindly longleaf pines with needles falling like snow in a breeze. The Florida Trail is��also the only national scenic trail with beach views, as it passes��along Panhandle sand as fine as sifted flour.

Kennedy says he’s debating hiking it again��despite the strange encounters and miles of difficult swamps. “It’s like any trail,” he says.��“You love it when you’re done with it.”