Bear bags are a stubborn fixture of the backpacking world. Hanging is recommended, taught, and practiced by influential organizations and individuals, even though it is less effective, less foolproof, less reliable, less efficient, and less safe than other food-protection techniques, notably hard-sided canisters and (to a lesser degree) soft-sided bear-resistant food sacks.

I have not hung a bear bag in at least a decade, and I find it to be so irrelevant that I no longer include a bear-hanging module in the for my guided trips. It’s an outdated and ineffective method of food storage, and backpackers (and bears) would benefit from a reprogramming of this topic.

What Is a Bear Hang?

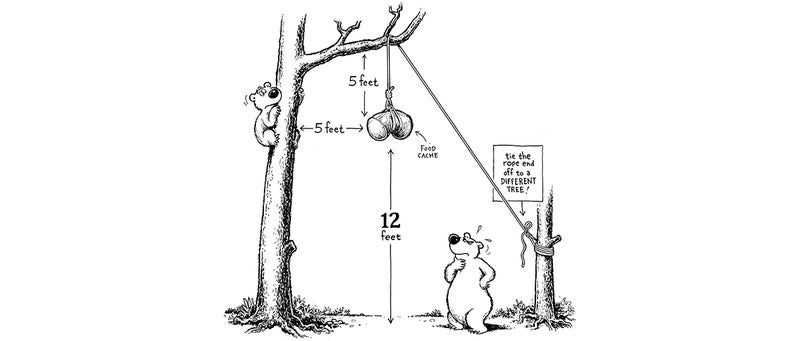

A bear hang is an improvised system of cord, sacks, or bags, and sometimes carabiners and pulleys, used to suspend food in a tree, primarily to protect it from black bears as well as from rodents (especially in high-use campsites) and grizzly bears (in select areas only). Generally, a rock is tied to a line and thrown around a branch, leading to something like this:

Recommended Alternatives

Recently, I gave in-depth explanations of my . But here they are in brief:

- If permanent infrastructure is available (e.g., lockers, cable systems), use it.

- If hard-sided canisters like the are required, carry one.

- If bears regularly (or even occasionally) obtain human food where you are camping, carry a hard-sided canister even if it’s not required.

- If you are camping in bear habitat but but there no reports of bears stealing food and no hard-sided canister requirement, use an or (which is also rodent resistant).

- When staying at high-use campsites in bear-free habitats, rodent-hang your food (see below).

Depending on the local risks and your risk tolerance, you may also consider . This is widely practiced, but few are willing to talk about it.

The effectiveness of most methods can be enhanced by a Loksak Opsack, which is a heavy-duty odor-resistant plastic bag with an airtight seal. On its own, it is an inadequate method of food storage.

Bear Hangs Versus Rodent Hangs

The concept of a so-called is the same as a bear hang: suspend your food in the air, out of reach. But it’s simpler and less robust: it can be kept in camp, placed only a few feet off the ground, and needs to protect only against mice, squirrels, rabbits, raccoons, and maybe an occasional fox.

Unlike bear hangs, I advocate rodent hangs. They’re perfect for bear-free areas, like most of the desert Southwest.

Reasons Not to Hang a Bear Bag

I no longer hang bear bags and never recommend it. The technique is plagued with problems:

1. You probably suck at it.

Like other outdoor skills, learning to properly hang a bear bag takes time and repetition. And because most backpackers don’t backpack often enough to get the requisite practice, most bear bags are hung really poorly. Like, they’re laughable and woefully inadequate.

But unlike other outdoor skills, the consequences of a poor hang are immediate and widespread. If you fumble with a or struggle to find , it impacts only you, and you can do it better next time. But a failed hang becomes a problem for the bear, for the land agency that may need to relocate or kill the bear, and for the next backpacker(s) who stay in or near your campsite.

If you plan to hang your food in bear habitat, you need to have mastered this skill already by practicing dozens of times in bear-free areas like your backyard or a neighborhood park. If you’re not willing to do that, you shouldn’t even consider hanging your food.

2. It’s often impossible.

The effectiveness of a hang depends largely on the tree in which the bear bag is suspended. It’s recommended that the bag is positioned about 12 feet off the ground, five feet away from the trunk, and about five feet below the closest limb.

Unfortunately, it’s often impossible to find a tree in which these thresholds can be met or exceeded. Above tree line and in arid areas, no trees are available. Near tree line, the trees are too stunted. In some regions, the dominant tree species are ill-suited, like the spindly lodgepole pines, Engelmann spruce, and subalpine firs found throughout the Mountain West. Still other forests have been ravaged by wildfire, mountain pine beetles, spruce bark beetles, and ash borer.

3. It’s time-consuming.

In a best-case scenario (i.e., a skilled hanger, a light food load, favorable trees nearby, and no mistakes), hanging a bear bag takes about 15 minutes. But it rarely works out that way. Why?

- Most backpackers have limited hanging skills and experience and are therefore inefficient.

- Heavy food bags require more hangs and/or more complicated systems.

- Perfect trees can be hard to find, resulting in long walks from camp.

- Mistakes are commonplace, e.g., the throw rock slips out of the knot, the throw misses its target limb, the rope gets stuck, the limb breaks, etc.

For soloists, I’d bet it takes about 30 minutes to set up; for groups, an hour. A bear-hang kit weighs less than a hard-sided canister or an Ursack, but the savings is entirely negated by its inefficiency.

4. It can cause injury or death.

The throw-rock is a hazard. It can bounce out or off of the tree in odd ways, and can snap back if you accidentally step on the cord while throwing it. It sounds like an elementary mistake, but it’s easy to do (I’ve done it) and it’s a common role-playing scenario in many wilderness first aid/responder courses.

Deaths are very uncommon but are needless and much more tragic when they do occur. Several years ago, the news of rocked the outfitter-guide community.

5. It’s rarely effective against a determined bear.

To put this point in context, let’s watch some videos. Black bears are extraordinary climbers!

Grizzly bears have less Spiderman-esque talent, but they shouldn’t be discounted.

Unless your hang is textbook perfect, a determined black or grizzly bear will probably get your food. No hang method is immune. Bears have been known to chew through cords, break tree limbs or trunks, and lunge at food bags, tearing them open as they fall. Sometimes they send their cubs out on the limb to do the dirty work for them.

I have met only one person who could truly bear proof his hangs. Kevin Sawchuk learned his craft in the 1970s, when hangs were still permitted in the High Sierra. Unfortunately, not everyone read or could replicate him, and land managers decided that hard-sided canisters were the most effective strategy against their wily black bears.

6. More user-friendly options exist for less audacious bears.

Thankfully, the High Sierra is the exception, not the norm. In most other areas, the black-bear population isn’t as healthy, and the bears don’t nonchalantly walk into occupied camps.

In these types of areas, bear bags are a widely accepted food-storage technique and are believed to be effective. But very few hangs are probably ever tested. It’s like wearing a garlic rope around your neck to keep away vampires—it must be effective if the vampires don’t get you, right?

Better options in these types of areas are the and . These bear-resistant bags are lighter than a hard-sided canister (25 to 50 percent of the weight for the same volume), pack more easily in a backpack, have been by the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee, and can be quickly and easily anchored to a tree.

I don’t trust Ursacks as much as a hard-sided canister, but I think they’re acceptable in low-risk areas where they’re unlikely to be rigorously tested.