The High Cost of Being David Brower

He rescued some of the West's hallowed lands. He became one of the most influential environmental leaders of the century. In the process, he sacrificed friends, family, and anyone who couldn't keep up. Now, alone in the twilight, how does the archdruid make peace with it all?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

September dusk in the hills of Berkeley, California, and David Brower is working in his office. He is writing a letter, and it's getting late.

He pauses often, pen tapping as he summons the rhythms and imagery to transform a string of mere words into something more powerful: a message. When he makes the slightest move to the side, his old swivel chair yowls in protest. Anne, his wife, has asked him several times to oil the bearings, but she doesn't mention it anymore. The screech of metal has become for her a kind of code: Short screeches mean her husband is working; a long screech means he is turning away from his desk and perhaps coming to bed. When she hears nothing, she comes to check, cane thumping down the dim hallway, to make sure her husband is where he should be, head bent over his papers, white hair ablaze in a cone of lamplight.

Brower works through sunset. After the letter, there's a book to look at, a luncheon to arrange, a grant proposal to examine, a radio interview to do, and then, perhaps after a martini, the real work begins.╠ř

Each afternoon, Brower's desk receives a stack of environmental journals, magazines, books, newsletters, updates, pamphlets, and broadsheets from all regions of the globe, reams of paper deepening at the steady rate of four inches a day. About twice a week, Brower dives in, tearing out pages, pressing down sticky notes, performing hasty origami on countless leaves of newsprint, cutting and pressing the anonymous flow with an imperial hand until only the vital information remains. Governments proclaim, scientists reveal, ambassadors declare, activists denounce, politicians waffle, and rebellions are crushed; human civilization gushes along on a torrent of print, and Brower inhales all of it in great thirsty gulps. Once he has done that, his instinct calls for utterance, expressive action. To tell them, all of them: Can't they see what's happening? Within the walls of his modest home there are 11 telephones, a fax machine, a typewriter, a laser printer, and a PowerBook. His latest goal is to write a newspaper column, preferably syndicated worldwide. He is learning his way around the Internet. He is 83 years old.

If there's enough time, Brower will fax some of his findings to one of the hundreds of environmental organizations with which he is affiliated, perhaps with a note: You have to see this. Maybe they'll turn up in the Sermon, the stump speech that Brower delivers in various forms a hundred or so times a year, a witty assemblage of eco-parables and scary statistics that says, in essence, (1) the earth's living body is under dire attack and (2) with energy and boldness it can be healed.

But there's never enough time. That is the point. So Brower simply reads the stack of mail and keeps going, making speeches and writing letters until there's more mail to wade through, more speeches to give, more letters to write. It never ends; if it did, so would Brower. He has made a preacher's bargain with life. He constructs messagesÔÇöon biopreserves and hypercars, wilderness restoration and population controlÔÇöand messages, in turn, construct him. They form the framework of his days, magnetically coupling him to thousands of anonymous faces with brief, intense sparks, each spark affirming his identity as the most charismatic, controversial environmental leader of the century.

Brower is wholly or partly responsible for what the movement considers many of its greatest rescuesÔÇöthe Grand Canyon, Kings Canyon, the North Cascades, Point Reyes, Redwood National Park, and Dinosaur National MonumentÔÇöand equally responsible for some of its most tragic losses, including Utah's Glen Canyon. He founded Friends of the Earth and Earth Island Institute and helped start the League of Conservation Voters. More important, Brower is a visionary in the most fundamental sense of the word. In the late fifties and sixties, using film, books, and the persuasive resonance of his voice, he taught the American public how to see and relate to wildernessÔÇöa skill being appreciated anew by activists dissatisfied with today's bloodless, technocratic approach. He is a cultivator of talentÔÇö”soft path” physicist Amory Lovins and population guru Paul Ehrlich were first recognized and encouraged by BrowerÔÇöand of an endless fount of ideas awaiting fruition, including the National Biosphere Reserve System and the World Ecological Bank, which would provide funding for preservation projects. Not all of his ideas take root, and Brower doesn't seem to expect them to. He is, as he puts it, a catalyst, a coaxer, a pied piper whose main function is “to turn on the lights.”

He is also, as numerous people will testify, holy hell to work with. Beneath his genial veneer lies an obsessive, uncompromising drive that led to a series of bitter disputes and his unhappy departures from both the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth. Prickly and single-minded, Brower seems always to move too fast, want too much, push too hard. No one can keep up. His sense of mission comes before allegiances, before friendship and family, before everyday comfort and affection. He's given a million dollars of his own money to support small environmental projects. Year by year, he has purified his life until all that remains is the David Brower ecological gospel in excelsis, the totality of which is contained in the most primal of assertions: I know.

But there is one reality that cannot be disguised. Slowly, inevitably, Brower's body is beginning to fail. He fights these changes as he fights everything he despises: stiff-arms them with clever wordplay, obliterates them with sheer will, steadfastly refuses to alter his course. His death, when it comes, will undoubtedly set off a rush to embrace his ideals and his memoryÔÇöboth of which are safe, easy to love. But for now there is just the old man in the lamplight, existing on the periphery of the movement he helped create, etching out messages for an unseen audience. Before our eyes, Brower is being transfigured into the embodiment of his own sermon, a living metaphor for a planet being consumed by itself. The difference, of course, is that his body cannot be healed. And Brower, the visionary, seems the last to see.

“How late will he work?” I ask. Anne shrugs. “I never know. Sometimes till two or three in the morning. Sometimes later.”

He has purified life down to his ecological gospel in excelsis, contained in the most primal of assertions: I know.

We walk to the back patio, and Anne pours strawberry-banana nectar into tiny glasses. She talks of their upcoming trip to the eastern Sierra Nevada, a reunion with old Sierra Club friends. She is looking forward to it warily. Brower's 1969 split with the Sierra Club was an earthshaking event, a source of such anger and sadness that tempers still flare despite courteous exteriors. “It could be wonderful,” she says. “Then again, it could be horrid. One never knows.”

Anne Brower is a small woman with shrewd, knowing eyes. She has been married to David for 52 years. Her friends call her a saint, because they can conceive of no one else who would have stayed with him. She won't agree, of course. To be a saint, one must do something.

“I'm very uninteresting compared to David,” she says firmly. “Everything has always been connected to his work. I've lost my identity.

“There was one time when I thought we'd finally get away for a vacation together,” she says. “It was back in 1969, after David was fired. I saw an ad for a beautiful house on Big Sur. We rented it for the year, and I even bought towels, thinking, 'Well, now he won't have to work so much anymore.' We stayed there one night. He went right on doing what he had been doing.”

After a while, the conversation turns to a more somber subject. From deep within the house, there's a faint squeak, and Anne nods as if to confirm it: He's still there.

“David doesn't think about death at all,” she says. “I think at my age there's nothing more exciting that's going to happen to me except dying. But he believes that if he were to think about death, it would keep him from accomplishing things. He wants to work up to the bitter end.”

“But why? Can't he rest awhile?”

Anne's eyes move quickly to mine. She looks mildly surprised. “Why, he has to save the world.”

David Brower is not a hard man to meet, he is hard to catch. He spends half the year voyaging on a dizzying wave of conferences, retreats, book readings, film festivals, lectures, and benefits. It's been said that he never met an invitation he didn't like. His quotidian duties include the chairmanship of Earth Island Institute, which he founded in 1982, and membership on the board of the Sierra Club, to which he was reelected this year. When in town, he can be spotted buzzing around the Bay Area in his slightly beat-up 1983 Corolla, the one with the FREE AL GORE bumper sticker. He drives the Berkeley hills like a dervish, accelerating into blind corners, downshifting on the fly. Following Brower is frightening, though the feeling is slightly attenuated by the realization that he was born four years after the introduction of the Model T.

Brower loves restaurants, particularly fifties-era seafood-and-steak joints with studded-leather booths and bartenders who know his preferencesÔÇöTanqueray martinis straight up, no distractions. He doesn't like to dine with just one other person, so he typically invites a crowd. More sociable, he says. Sinbad's, on the Embarcadero, at one.

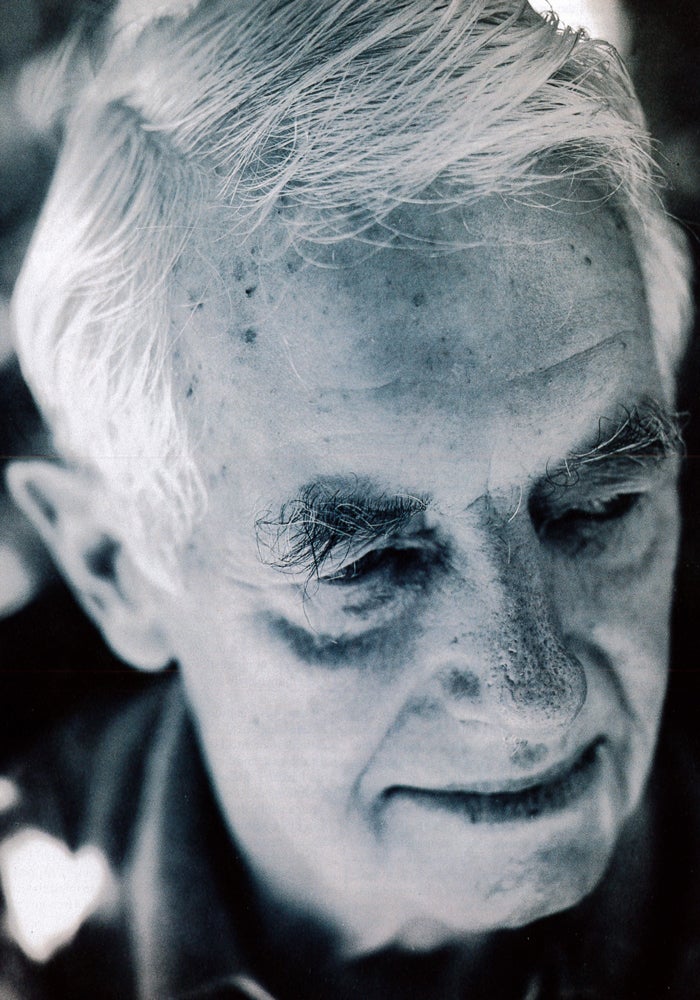

The voice is what one notices first. Not that the rest slips past. He's a big man, with the rawboned physicality of a former football star. The unclimbable crag of a face, totemic cheek-creases, wild blooms of eyebrows, glistening blue eyes, and a halo of pearly hair combine to create such an aura of spiritual heft that it's a good ten minutes before one notices that Brower is something less than an image of sartorial splendor, outfitted in his customary garb of a T-shirt and well-frayed blazer, mismatched polyester pants, and inexpensive running shoes with Velcro closures. Bowed legs and a sore kneeÔÇöthe latter partly a result of a 1936 ski injuryÔÇölend a hint of a John Wayne saunter. When he walks across a room, eyes track him, and Brower looks resolutely at the floor. It's hard to tell whether he's shy or just looking where he's going.

But the voice, so vigorous and yet so intimate, is what stands out. Brower begins each sentence in the tenor register and slides into a velvet baritone, looping melodies around themselves, hitting words with unexpected emphases so that the listener has the sense of hearing them for the first time. He doesn't speak words so much as play his voice, a cornetlike music that spirals above the atonal chug of normal conversation. There is no gap between Brower's public and private dialects, as sometimes occurs with public figures. Furious, depressed, or asking would you please pass the salt, Brower sings. “When he's speaking to a crowd, it's like he's whispering to you,” says Patrick Goldsworthy, an old friend from the Sierra Club. “He says things with feeling.”

Brower found the voice in the early 1940s when, as a shy mountaineer, he was asked to talk in front of 200 people on a Sierra Club High Trip. He doesn't remember much about what he saidÔÇösomething about the landscape, the mountains. But standing there, in front of the campfire, something inside him awoke. “He used to be so quiet,” Anne says. “Now you just drop in a nickel and the cassette plays.”

“Now, take a bird's feather, for instance,” Brower says, spearing a shrimp. “I just marvel at that structureÔÇöthe hairs, the spacing, the pattern. It's a very nice bit of design, enabling it to fly, to handle temperature changes. Or look at beetles. Did you realize that there's a beetle that can produce steam to fire at enemies? There's a clam that can manufacture cement at the temperature of seawater. What's the trick? We have no idea. If we found out, we might pave everything in sight.” He chuckles, with a quick glance to make sure I'm chuckling, too.

“There are certain advantages to being an octogenarian. For instance, I can be outrageous. I was only mildly outrageous before 80, but now there's nothing they can do to hurt you. They might, of course.” He smiles into his Tanqueray. “But probably not.”

He recites poetry. He counts pelicans, noting that his all-time Sinbad's lunch record stands at 176, happy hour included. He seems content, an emotion that militant environmentalistsÔÇömilitant anybodies, for that matterÔÇöaren't supposed to possess after a half-century of throwing themselves into the establishment's toothy maw. Even his pacemaker, recently implanted to correct a mild fibrillation, is charmingly evoked. “My doctors told me to get this pacemaker so I could keep up with myself,” he says.

But between the riffs, there's silence. Long, awkward, fork-scraping silences. Anne shoots guests a sympathetic look. Words possess tremendous power with Brower, but he cannot or will not employ them for small talk. He won't ask about you, and he would prefer if you didn't ask too deeply about him. His words fly up and out; they soar like so many pelicans. Then you wait until more appear.

Even with his closest friends, Brower can sit for an hour and not speak. He's ephemeral at social gatherings, preferring to avoid them or linger in a corner. At conferences he hovers near the door, unless he's at the podium. He's more at ease with a thousand people he doesn't know, his friends say, than with one person he does.

His behavior forces his friends to explain, and so they do. He's shy. He's preoccupied. He's aloof. He's humble. He's arrogant. He's honest. He's scared to death of people.

Some boil over in frustration. “He could have become a nationally known leader,” says former Sierra Club colleague Jim Moorman. To Brower, however, speculation is moot. He can't changeÔÇöand even if he did, what would be the cost? What places wouldn't get saved? What ideas wouldn't be born? Besides, as he likes to say, “I don't like people telling me what to do.”

ÔÇťA ship in harbor is safe,ÔÇŁ Brower says. ÔÇťBut that's not what ships are built for.ÔÇŁ

Of course, personal costs have piled up, but Brower, ever optimistic, ever in control, has always managed to deal with them. Friends no longer speak to him? Forgive them, then find new ones. Environmental groups fire him, call him selfish and irresponsible? Start another group. Start two-they'll come around. Children grow distant in your absence? Take them on unforgettable adventures; they'll come around, too. But keep moving forward. “A ship in harbor is safe,” he likes to say. “But that's not what ships are built for.”

While Brower remains for the most part in good health, his body has suffered breakdowns: bladder cancer ten years ago, recurrent sciatica, a fainting spell before the pacemaker was implanted. In public he deals with mortality in typical Browerian style, kidding about applying for a 20-year extension and stating his fervent hope that the recipient of his dust will have as much fun with it as he himself is currently having. But mostly he deals with it by not dealing with it, traveling incessantly.

“Some people need money, some people need power,” says Edwin Matthews Jr., a former Brower prot├ęg├ę at Friends of the Earth who split with him over management style. “What Dave needs is to be appreciated. Or maybe to be loved. He's in his element telling a story he's told 500 times to a group of people 50 years younger sitting around him in a circle, listening.”

Part of his work is to oversee the creation of his own legacy. The two volumes of his 904-page autobiography, For Earth's Sake (1990) and Work in Progress (1991), are less the story of Brower's life than a meticulous exhibition of his old writings, reflections, and wish lists, a kind of museum of the interpreted self. He wrote his most recent book, an extended sermon titled Let the Mountains Talk, Let the Rivers Run, in a focused stretch of four months, giving coauthor Steve Chapple the distinct impression that this was “his last shot at getting it right.”

“He has faith in his destiny,” says Martin Litton, an old friend and ally who served on the Sierra Club board from 1964 to 1972. “He feels he was placed on earth to do these things that no one else can do.”╠ř

Those close to him say that even as Brower continues at an unrelenting pace, he has also begun to repair broken relationships. He is paying more attention to his family. A few years ago Anne began accompanying him on some of his travels. He says “love you” when he tells his children good-bye, and he looks them in the eye when he says it. He attempts what for Brower borders on the inconceivable: He sits around and talks about nothing at all. The old ship is trying, with supreme difficulty, to get accustomed to harbor.

“I like him a lot better now,” says his daughter, Barbara, a professor of geography at Oregon's Portland State University. “He's a more attentive father, and he's turned into a good grandfather. His humanity has increased.”

To Brower's surprise and pleasure, his 49-year-old son, Bob, has offered to accompany him and Anne to this weekend's High Trip reunion in Lone Pine, California. The second of their four children has been beset by what are gently called “Bob's troubles”ÔÇöa head injury from a motorcycle accident, bad luck with jobs and women, and other, more personal demons.

“This trip will be good for Bob,” Brower pronounces, draining his coffee. “Getting out into the wildness will help Bob be Bob again.”

Another long silence. Chairs shift. Then Brower stands abruptly, announces that it's time to go, and walks toward the restaurant door.

Strawberry Creek was a fine place to grow up. Its upper reaches were a rolling paradise of trails, and that's where David Brower spent his days. The Browers were like other families who lived in the crude Victorian houses on Haste Street, a stubborn and religious mix of third- and fourth-generation immigrants. His father, Ross Brower, taught mechanical drawing at the University of California, Berkeley, on whose undeveloped campus Strawberry Creek flowed. David, one of four professor's kids, had the run of the hills, bicycling, hiking, and catching butterflies, which he pinned on cardboard. He was a solitary boy, and this was his kingdom.

Things got tough when David was in the third grade. The university fired his father, who had to manage apartments to get by. Around the same time, his mother fell ill. Her vision slipped awayÔÇöan inoperable brain tumor, they were told. One day David stood wordless at the foot of her bed as she peered at him, trying to guess who he might be.

Their walks began as a way for David to escape chores around the apartments. But his mother loved the hills and found the strength to walk for hours. They went again and again, the tall woman and her bowlegged boy, as far as they could walk, past the farthest reaches of Strawberry Creek to the top of Grizzly Peak, where you could see the whole world. She gripped his left arm and he led the way, telling her where the rough places were. And other things, too.

Now we're in the pines. The fog is clearing. There are some wildflowers in the clearing, and a red-tailed hawk flying above them, looking for field mice. There's a breeze coming off the ocean. It'll be beautiful at the summit. This way.

Put him anywhere in the Sierra at night,╠řthey said admiringly, and he would know where he was by sunrise.

It was good preparation, walking those hills. His boyhood friends used to joke, “He who follows a Brower never follows a trail,” and their words would remain true throughout his life. Whenever Brower reached a personal or professional crossroads, he could sense where he wasÔÇöand, more important, where he wanted to be. To others he would sometimes look foolish, lost. But Brower didn't mind: He was in motion, rising above the rest, and if his friends didn't come along, well, he would wave to them when he got to the mountaintop.

After dropping out of college during the DepressionÔÇöthe established road to higher education never suited BrowerÔÇöhe paired with various friends and disappeared into the Sierra for weeks. Toting Survey of Sierra Routes and Records and a bag of small notebooks to leave as registers, they set out to leave their names on as many peaks as possible. They cached food in candy cans and huddled through storms without tents. Brower was nearly six-foot-two, 170 pounds, and rawhide-strong. He was the happiest he had ever been.

Inevitably, he met people who liked to do the same thing. Sierra Club members traveled in big groups, wore jaunty alpine hats, sang campfire songs, and talked about the sainted founder, John Muir, who had implored them to “explore, enjoy, and preserve” these mountains. It became their trinity. Gradually Brower grew to like their gracious camaraderie, their clannish verve. These were talented, first-rate peopleÔÇölawyers, doctors, writers from pedigreed California families. And they liked him. Put him anywhere in the Sierra at night, they said admiringly, and he would know where he was by sunrise.

The club became family, and soon Brower was wearing an alpine hat and leading High Trips, the 200-person, two- and four-week outings. Scissoring along on his bowed legs, he walked faster than anyone, and more optimistically. “Brower miles” became a running gag. Dave's got a place that ain't on the mapÔÇöhe says it's just a mile away. Then they'd bushwhack a half-dozen miles and find themselves someplace unforgettable, Brower yodeling in triumph. Roping up with fellow Sierrans, he tackled difficult first ascents, like that of Shiprock in New Mexico, for which his team employed a new device called an expansion bolt. With his long reach and flowing style, Brower usually climbed lead, and he scored more than 70 first ascents. Camel Cigarettes wondered about the possibility of his becoming a spokesperson, and with good reason. Club women swooned over the tousle-haired Adonis; they would lie down in the trail for him, it was said. But he stepped over. There were always more places to go.

For Brower, the only thing that compared with climbing was writing. He spent winter nights bent over his desk at home, transforming the sensory clutter of his expeditions into words, images, and stories. On the expanse of the page, the expeditions were different, more clever, tidy, as if he had tapped into a sort of parallel reality that stripped away all the nonsense and cut immediately to the important things: beauty, truth, heroism, wilderness. He liked it immensely, this word-magic, and he could tell that he was good. He landed a job as an editor with the University of California Press in 1941 and, at about the same time, won a seat on the Sierra Club's board of directors. On High Trips, people began asking him to speak. They sat around him in a circle, and Brower could see their eyes shining in the firelight.

At his new job, he shared an office with a woman named Anne Hus. She was an editor too, worldly and whip-smart, and they sipped sherry at her parents' house. Brower, now 29, needed near-violent prodding from his Sierra Club friends to keep up the pursuitÔÇöafter all, he was heading off to fight the Germans, and she was engaged to another. But her engagement broke apart. From a train on the way to officer candidate school, he wrote a letter proposing marriage. She wrote back. Two weeks after their wedding, they went to a movie. It was their first real date.

When Brower returned from the war. He threw himself into Sierra Club works. But he was interested in fulfilling the last part of Muir's trinity. Mountains could be ruinedÔÇöhe had seen it in EuropeÔÇönot by bombs, but by far more dangerous weapons: roads and bridges, ski chalets and power lines. Now here was a cause to believe in.

His timing was perfect. Fueled by postwar expansion, the Bureau of Reclamation was looking to dam the Colorado River in Utah's Dinosaur National Monument. The club's leadership decided to organize, to motivate, and Brower took the lead. They made him executive director in 1952. Nobody knew what an executive director did, since the club had never had one before. But whatever Brower did, that was it. Give riveting testimony before Congress. Make headlines. Build public support. He filmed and narrated wilderness-awareness movies on Yosemite and the North Cascades. He invented a new genre of book, monstrously big, wildly expensive exhibits of heartbreakingly beautiful wilderness photos by his friend Ansel Adams and others. The books were Brower's special pride. He determined the tint of each photo, the placement of each comma. Move the readers to tears, he said, and their action will follow. He was resoundingly right. Club membership increased from 7,000 to 77,000 during his tenure (today it hovers at around a half-million). Pundits say he invented environmentalism for the media age, but what he really did was something simpler: He took the American public by the hand and showed it what he saw.╠ř

Meanwhile his own family was growing up. Most of the child-rearing fell to Anne, of course. David was too busy, too involved. Anne uses the word “encapsulated.” She could drop a dinner plate behind him and he'd keep working. Sometimes birthdays and other special occasions slipped past. “You don't know me from the girl next door!” his daughter, Barbara, screamed at him. “Of course I do,” Brower replied without missing a beat. “She's a little taller and has blond hair.”

There was so much to do. When the bureau tried to dam the Colorado River near the Grand Canyon, he ran full-page ads in the New York Times, one of which read, “If They Turn Grand Canyon Into a Cash Register Is Any National Park Safe?” Perfect! Public sympathy swelled, the dam was scuttled, and though the club was stripped of its valuable tax-deductible status (IRS regulations prohibit direct political action), the loss was more than offset by small, nondeductible contributions. Brower called for more books, more words, more pictures. More action! He was featured in Life magazine. When the board of directorsÔÇösome of whom were old climbing palsÔÇöobjected over the tax issue or worried that too much of the club's budget was tied up in books, he ignored them, or threatened to resign, or used that voice of his. Is it more important to keep the bottom line black or the earth green?

Battles were being won: Dinosaur, the Wilderness Act of 1964, Point Reyes National Seashore. Lost battles, like that over Glen Canyon in the late fifties, held even more powerÔÇöBrower never visited the canyon but agreed to its being dammed in exchange for the cancellation of two other dam projects in northeastern Utah's Echo Park and Split Mountain. When the dam that would soon create Lake Powell was being built, Brower made repeated pilgrimages to the place, compiled films, commissioned books, and transformed his shortsightedness into a cross that he still bears. “Glen Canyon died in 1963 and I was partly responsible for its needless death. So were you,” he wrote in The Place No One Knew (1963). He vowed never to commit the same sin again.

Relations with the club's board, however, worsened. Friends wrote him letters, pleaded with him to change his ways. (“Please take a good, long, objective look at the present aspect of the Club, its finances, and its programsÔÇöand, very important, at yourself!!! As ever, Ansel.”) But Brower wouldn't change. He ignored lines of authority and spent money without board approval. Seemingly oblivious to rising financial problemsÔÇöthe club lost $100,000 a year in 1967 and 1968ÔÇöBrower demanded a costly international series of books. How could he change? The bastards weren't resting, and relentless action was the best way to get more money. Couldn't they see?

In 1969 they fired him. Technically it was a resignation, but everyone knew the truth. First a coldly worded telegram relieving him of fiscal responsibilities, then a series of votes. “The Happening,” Sierrans called it in hushed tones. Almost all of Brower's friends voted against him, including Adams. The Sierrans salved their doubts by talking of “cleansing” the club, by comparing Brower to a noble but foolish climber who got too far above his protection, who hurt the club by taking selfish risks. How could they understand that there was no self left to risk? He was on a mission they couldn't imagine. This was bigger than rivers, bigger than any lines on the map. They would see, once he got to the mountaintop.

As we get ready to leave for the Sierra Club High Trip reunion in Lone Pine the next morning, Brower putters around his house, looking for something. He moves carefully in the labyrinthine spaces of his living room, bending into corners as if he were sniffing orchids in a garden.

“I know where it is,” he says. “It should be right here.”

Elbow-deep in a stack of papers, he extracts his quarry, a magazine story on Yosemite. He places it carefully on another stack and moves on, tracking down something else.

“Could you give me a tour of the house?” I ask. Brower does not turn. After a moment I ask again, and he looks at me incredulously. Where would he begin? With the 100 or so file boxes stacked in every possible crannyÔÇöten under the baby grand piano, six behind the couchÔÇöwhich serve as the repositories of his daily clipping and filing? Or with the warrenlike basement, where Bob Brower resides, its windows covered by more boxes? Or perhaps with the rocks, the hundreds of granite, limestone, quartzite, agate, and sandstone keepsakes, many from Glen Canyon, which lend the distinct impression that a glacier has just receded through his living room? Or out on the patio, with the four garbage cans brimming with golf balls, the fruit of Brower's morning strolls near the links, colors in one can, whites in the others? Or perhaps the bedroom, the door of which is papered with dozens of tattered name tags, each reaffirming the identity of the person within: HELLO MY NAME IS DAVID BROWER. Brower cannot give a tour because the meaning of his home, like the meaning of himself, is not found in any individual object. Everything here is equivalent, possessing significance only within the arc of relentless action that created it.

“Here are some pictures,” he says finally. He points them out, one by one: black-and-white portraits of him and Anne the year they married, smiling grandkids captured in a snapshot, the surreal poise of an Ansel Adams landscape, images of family closeness, of wilderness, of a life rich in people.

╠ř

But these images aren't complete, not as a record of relationships. Where are Dick and Doris Leonard, his best friends during the early Sierra Club years? Where is Dan Luten, his old next-door neighbor, fellow mountaineer, and longtime colleague? Where is Edwin Matthews? Where are Wallace Stegner, Phil Berry, Mike McCloskey, Dr. Luna Leopold, all the others?

Unlike his wife (“I hated them all,” says Anne of the Sierrans who voted against her husband), Brower says he holds no grudges. In the months after the Happening, he was determined not to become a pariah. He kept his membership and did his best to maintain the social ties despite lingering tensions. In 1983, when the petition was circulated to renominate him to the board, he made a special point of obtaining the signatures of old friends such as Adams. When Brower encounters former colleaguesÔÇöas he will this weekend at Lone PineÔÇöhe exudes cordiality, and it is usually returned in kind. After all, there's important work to be done, work that transcends personal disputes. But no cordiality can resurrect the promise of these relationships. They are shadows, ghosts of a time long past.

“Brower overlooked certain aspects of human relations that are important,” says Hal Gilliam, former environmental columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle. “He never made amends, never apologized for his mistakes. I know so many people who worshiped him and then were turned off.”

Some ghosts are more corporeal than others. Dick Leonard was Brower's strong-minded mentor and climbing buddy; people said they seemed like brothers. In 1952 Leonard pushed for Brower to become the club's executive director, and in 1969, saying he had to preserve the organization, he orchestrated Brower's removal. Brower carried no rancor, making a point of celebrating each New Year's Eve with the Leonards, as always. But a few years ago Dick fell ill. It was a long and painful ordeal; friends wept at seeing the once-powerful climber trapped at home in a wheelchair, blind. But Brower never wept with them. Though he lived less than a mile away, he never visited. Doris Leonard, puzzled and saddened, could only conclude that it wasn't her husband Brower was avoiding; it was the other presence in that house.

Brower has a recurring nightmare. In it, he is trying to get something doneÔÇöpacking for a trip, cleaning the houseÔÇöand he can't finish in time. He is sweating and trying hard, but the work keeps piling up and the clock keeps ticking. The harder he tries, the worse things get. And then it's time.

Within days of leaving the Sierra Club in 1969, Brower was on the move. With a few loyal staffers and thousands of disaffected members, he set out to realize his vision of what the Sierra Club could have become: a global, media-savvy, politically muscular activist group. He called the new organization Friends of the Earth, and it would be the first truly international environmental group. Newly christened the archdruid of environmentalism by John McPhee's New Yorker profile, Brower attacked on all fronts: Nuclear weapons. Solar energy. Population control. The California condor. The Alaska Pipeline. Toxics. Whales. Brower's role was to act as visionary and catalyst, traveling widely, casting his net. He preached the Sermon to thrilled campus crowds, always ending with the Goethe couplet that had become his credo: “Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.” Then he'd look at the rapt faces and say, “There's magic in you. Let it out.” You could hear a pin drop. It was marvelous.

Meanwhile his children had grown up. The three boys, like their father, weren't overly enamored with college. Ken worked on his writing (which like his father's was concerned with the environment), Barbara studied geography, and Bob and John pursued less structured endeavors, dabbling in electronics and recycling, respectively. They were too old to go on summer trips now. There were the usual modern family painsÔÇöhospital visits, broken relationships, fumbling for careersÔÇöand David simply didn't have time to come home and play catch-up. He would later calculate that in the first 40 years of his marriage, he spent an aggregate of 25 years away.

Almost from FOE's beginning, board members were worried. Money came rapidlyÔÇöthe group had a $1.5 million budget within a few yearsÔÇöand departed just as quickly. Led by Brower's enthusiasm, FOE started dozens of new projects each year. Every few weeks or so, some young person would walk into the Pacific Avenue headquarters: Hi. Dave, uh, hired me to work on overgrazing. The staff swelled to 50, triple that of comparably budgeted environmental groups. But every time FOE tried to get its financial house in order, there was Brower, eyes glistening, singing in that incantatory voice. We can work faster, better, harder. We'll get more members, sell more books, take on more projects. He was unstoppable.

But by the mideighties the FOE board had heard the voice too often. The coffers were nearly empty, and the staff had divided into virulent pro- and anti-Brower factions. Three successive presidents had resigned, chorusing protests that their work was being undercut by Brower. New kids kept strolling in. “Founder's syndrome,” pronounced a management consultant, diagnosing a disease with only one known cure. So in 1986 it happened again. Another board vote, another ousting, another round of damaged friendships and bitter recriminations.

Within months, Brower emerged with another group. This time, he swore, he was through with bureaucracies and boards. Earth Island Institute would be built according to the Brower model: an umbrella organization for small projects, each responsible for its own staffing and its own wallet. The scheme has worked out pretty well. EII has made a name for itself through the dolphin-safe tuna campaign and other successes. Brower gets to be Brower, shaking up worldviews with big ideas. Infuriated as ever by inaction, he still makes noise at board meetings, threatening to resign three times in recent years. “He gets frustrated that Earth Island doesn't have the infrastructure like he had at his other groups,” says Chris Franklin, Brower's personal assistant. “He stands up at meetings and does an I'm-going-to-take-my-ball-and-go-home sort of thing.”

These flare-ups are part of the primal drive that has defined the course of Brower's life from mountain climber to environmental agitator to ethereal visionary, the same drive that in its intransigence created a place like Earth Island Institute. This is where he belongs, among people yet profoundly apart. He does not wish to cause distress; he simply has no choice. He must take people by the arm and lead. This way.╠ř

The tiny town of Lone Pine, California, lies on the border of two universes. To the east stretches some of the harshest desert in America, trailing down to Death Valley, 104 miles away. To the west swells the 14,000-foot rampart of the southern Sierra, including Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the Lower 48. Lone Pine sits in a narrow shelf between the two worlds, cushioned by chaparral and cottonwoods, fully belonging to neither.

It's a good setting for a High Trip reunion. Club members have come from as far away as Maine. They gather outside town on Friday evening, next to a small lake in the shadow of Mount Whitney, about 50 people in all. They arrive wearing trail regalia, neckerchiefs and too-snug jeans, toting coolers of beer and dilapidated photo albums. Teeth flash in shouts of greeting; bear hugs knock hats to the dirt.

The Brower family arrives late, just before sunset. Quietly, with David leading, they pick their way to the edge of the group. David seats his wife in a comfortable chair before finding an adjacent log for himself and Bob. He deftly fixes drinks from his nylon daypack, an old-fashioned for her, a martini for himself, straight up, no distractions. Then he leans forward, elbows on his knees, and looks around. A warm wind blows from the desert; the air tastes of sage. The noise of the far-off highway is hard to distinguish from the papery rev of dragonflies. Brower's eyes move around the campsite, taking it all in.

He looks at the people. There are no ghosts here, no old rivals of battles past. These are only faces, some recollected, some new. Brower waits for them to come over. By and by, they do.

“Do you remember me? I was 12 when you led us on a Yosemite trip.”

“You always walked so fast, DaveÔÇöand it don't look like you've slowed down much.”

Brower smiles and nods, and the visitors wait expectantly for small talk. A colorful story, perhaps, or a fond recital of names and reminiscences. Anne smiles at them. “Aren't these gnats amazing?” Brower says.

Then something makes him stop. He takes a few deep breaths and attempts to speak. He can't. The words won't work. They come out garbled, insane, sputtering off his lips.

He's looking at the small cloud of insects hovering off his shoulder, a mad tornado of feathery motes. He lifts his big hand and slowly moves it through the gnats; they repool instantly. He does it again and then stares at the creatures. “What's their method of communication?” he asks. “What sort of compass do they use to figure out where they need to go? How do they talk to one another? These are some of the things I'd like to know.”

Hands rise and touch gnats. Brower smiles and raises his martini in a toast. “Amazing. If we humans could only communicate half as well, everybody might get along a little better.”

People chuckle. Brower chuckles. Alone at the other end of the log, Bob sips his beer and watches his father. Brower leans forward, and the words begin to pour forth. He talks about the Internet, the importance of learning multiple languages, the foolishness of Bob Dole, and the role of religion in society. He talks, and people gather, dragging lawn chairs, magnetized by the passion of his voice. Then Brower notices something.

“Look!” The group follows his outstretched hand. “Look!”

Brower is pointing at the hills a few miles to the east, over which a glowing rim has appeared. The harvest moon. Round and opalescent as the iris of some monstrous eye, it slides into view, decorating the windblown lake with a thousand glittering replications. The air resounds in childlike coos and adolescent howls. But Brower's voice chimes above them all, calling out numbers: the distance between Earth and the Moon, the distance between each and the Sun. He is letting this little gathering know, within a few miles, precisely where they stand in relation to the rest of the galaxy. He stands, his hair lustrous in the moonlight. I know.

Later, in the flicker of the campfire, someone pulls out a guitar. With rusty voices, the group launches into the old hiking songs. They sing “The 12 Days of Hiking” to the Christmas tune, jubilantly hollering, “Five Brow-er miles!”

Then Brower sings. It's an old song from the beginning of the century, a ballad whose words nobody else could remember, a tragic song about a family broken apart by love and fate. The guitarist tries the first verse, but then loses the melody. Brower keeps going. Lit by firelight, holding a little dog that has found its way to his lap, Brower sings sweetly and alone.

The next morning Brower has bristlecone pines on his mind. The organizers have scheduled a slot of free time, and he's planning to drive the hour north to Bishop to check up on the planet's oldest living inhabitants. It's been 50 years since he's seen them. “I want to see how they're doing,” he says. Brower is sitting in a small deck chair next to the outdoor pool at the Dow Villa Hotel, where the group has gathered for sweet rolls and coffee. Bedecked in shorts and a short-sleeved sportshirt, Brower blends faultlessly with the camera-necked specimens of Turista americana. He's also as antsy. “Where's your son?” he asks Anne. She shrugs. Bristlecone pines can wait.

Bob finally arrives and settles in for coffee. Brower shifts his chair so he can see Whitney's summit and talks about the speech he is going to give at tonight's dinner. He wants to ignite the revival of full-scale High Trips, which were discontinued in the early seventies because of the Forest Service's concerns about impact, among other things. It's an old issue, and in all likelihood a dead one, as mule-supported group tours have gone hopelessly out of fashion, supplanted by mountain bikes, ultralight packs, and other so-called advances. But nothing is hopeless.

“We allowed ourselves to be stopped, and we shouldn't have,” he says. “High Trips were exactly what John Muir intendedÔÇöthey were the first ecotours. And we let somebody tell us we couldn't do them?”╠ř

Then something makes him stop. He takes a few deep breaths and attempts to speak. He can't. The words won't work. They come out garbled, insane, sputtering off his lips.

He sits up straighter and inhales deeply, filling his chest with oxygen. His right hand feels for his left wrist. He tries to count the beats of his pulse, but the numbers won't fall in line.

Bob notices. “Dave, you OK?”

His father manages a nod. But his vision blurs and shimmers; he can't see Bob, Anne, anything. He needs something immovable, something real. He turns and looks up, past the cool white metal of the swimming pool fence, to the Sierra. But Mount Whitney buzzes and wavers. He stares for more than a minute, squinting and glaring ferociously, attempting by force of will to make the mountains stop. They will not.╠ř

“Dad, you OK? You need some oxygen?

Brower doesn't hear. He steeples his hands around his mouth, his lips moving. He is not praying.

When the paramedics arrive, his pulse is 58 and weak, his respirations shallow. They strap an oxygen mask over his face and wrap him in a rough blanket. Since he is conscious, they ask questions: Who are you? What day is it? He answers only one. “I'm David Brower,” he says.

In the waiting room at Southern Inyo Hospital in Lone Pine, there's ranch oak furniture, a soda machine, and a softly humming clock. The nurse asks what religion she should write on the admission form. “None,” says Anne, and then corrects herself. “Put 'Lapsed Presbyterian.'”

Anne and Bob sit quietly, having shifted into the unnatural placidity that emergency rooms require. Bob flips through an electronics magazine; Anne taps her cane handle. Encouraged by the reviving effect that the oxygen seemed to have, they haven't permitted themselves to consider the possibility that this could be anything more than a faint.

“I think all he needs to do is go back to the hotel and sleep a little,” says Anne. “Then he'll feel better.” Then to me: “I'm sorry you didn't get to see the bristlecone pines.”

The doctor comes in, a lean young man with sympathetic eyes. Gently, he asks a few questions and then sums up the situation. Anne and Bob listen intently, comprehending only scraps of meaning. Possible blood clot. Brain. AphasicÔÇöhe's having trouble using words. These things often pass, he tells them, but it's best to let him sleep here and then go to Bishop for a CAT scan in the morning.

“Your husband is one of my heroes,” he says.

“Oh, you're another one of those,” replies Anne.

An hour later in the waiting room, the situation begins to sink in. Deprived of oxygen, part of her husband's brain has stopped functioning. It may function again. It may not. Anne's eyes focus on the clock. For the first time, she looks weary.

“He suppresses the idea of his dying because he has so much he wants to do,” says Anne. “I think it may not be good to suppress those thoughts. I don't. I think about it every now and then. He never does, and it comes out in bad ways, like it did today. In his feeling really…lonely.”

“I knew it was serious when the paramedics were talking to him and he says, 'Bob, what should I do?'” says Bob. He shakes his head. “He's never asked me that before. Not ever.”

“I plan to have, at his memorial service, great big baskets of rocks,” says Anne. “I'll say, 'I know David loved those rocks, he got them all, so please take 30 or 40 with you when you leave.' I hope to get them all out of the house then.”

Brower's condition steadily improves. When Anne comes to his bedside, he recognizes her and speaks clearly. His strength seems to be coming back, though his vision hasn't. When he looks into someone's face, he can see only one eye.

Through the night, every hour or so, a nurse wakes him. Where are you? What day is it? What's your name? They carry pen and paper to write down his responses should he make any mistakes. Earlier Anne asked him if she could bring any books or newspapers from the hotel. He said no, not tonight.

The next morning Brower is sitting up in his hospital bed. His legs are casually crossed, the remains of his breakfast scattered on the tray in front of him. Wires trail from beneath his polka-dot gown, sending information to unseen machines. Anne is relieved to see that he looks himself.

“They seem to water the lawn here a great deal,” he says, pointing out the window. “I hope it's just in the morning and evening and not in the heat of the day. That would be a waste.”

Without prompting, he takes us through the incident in vivid detail, as if he were talking about one of his climbs: the initial dizziness, the inability to speak, his attempt to make Whitney sit still. The sentences stream forth in a smooth narrative flow, each word carefully chosen. With image and rhythm, he is creating a story to obliterate the ravages of his body.

But there comes a point in his telling when everything stops, when he arrives at a nothingness where words don't exist. He doesn't know what happened, because he wasn't there. This is where his story ends. This is where Brower cannot be Brower anymore. He can only be human.

“It was scary,” he says. “I didn't like it at all.” Then, more plaintively, “I want to go home.”

“Poor dear,” says Anne, laying her hand upon his.

And after a while, he will go home. He will go home where the doctors will tell him he has suffered a stroke and give him pills to thin his blood. His daughter will fly in from Portland and straighten the office up, and he won't particularly mind. Though spelling will confound him for a while, his speech will come back with full vigor. Soon he will joke with audiences about his “conking out,” using his story to create sparks of energy and affection. This incident will be folded into his identity and will provide him with new words to loft out into the night from his old swivel chair, new messages to tell us where we are and where we need to go.

But for now he needs a CAT scan in Bishop, and the ambulance thrums outside. Brower looks at the gurney disdainfully but realizes that he has no choice. Straight-backed, with great dignity, he sits down and swings his legs up. The paramedics touch a hidden lever, and the gurney springs skyward, raising him four feet off the floor. He leans back, knits his fingers behind his head, and looks toward the door.╠ř

“Here we go,” he says.

Daniel Coyle, a former senior editor of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, is the author of Hardball: A Season in the Projects, published by G. P. Putnam's Sons. His feature on the world's fastest men appeared in the June issue.