We’re blasting through the heart of the New Mexican desert, accelerating full-throttle along a lonesome two-lane blacktop that stretches pin-straight to the horizon. I’m on the back of John McAfee’s Tanarg iXess speed machine, feeling the power in the base of my spine as the mesquite bushes on either side blend into green blotches. It’s like a quintessential balls-to-the-wall motorcycle moment, but only for another 2.5 seconds. When McAfee pushes forward on the bar in his hands, the triangular wing over our heads pitches up, and with a lurch the road and the desert fall away beneath us. We climb and bank, curving over the scrubland toward the canyon to the west, our shadow sending the jackrabbits below scurrying for safety.

Welcome to John McAfee’s world. Literally: You’re welcome to it. If you happen to find the idea of zipping over a desert landscape at cactus-top altitudes at all appealing, you’re invited to come hang out in the New Mexico desert with John and his band of like-minded companions. He’s built a facility, in fact a network of facilities, to promote a sport that he all but invented and has decided is the most fun on the planet. This, to McAfee, is no small matter. Since amassing a megafortune through his eponymous antivirus software, and then another fortune with a follow-up tech venture, McAfee has chucked the world of business in favor of full-time fun. And to McAfee, fun is serious business.

“What if sex were a secret, and you stumbled onto it? You’d say, ‘I’ve got to get the word out!’” McAfee says. “The advantage of my having achieved some degree of financial success is that not only can I put my resources into the thing I love, I can spread the word.”

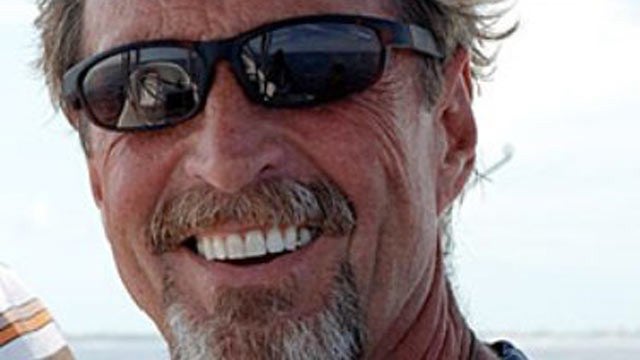

JOHN MCAFEE TENDS TO take people by surprise. In my case, literally so. It was past midnight, and I’d spent the last three hours driving east from Tucson to the tiny hamlet of Rodeo, New Mexico. The turnoff from the highway to McAfee’s dirt road isn’t marked, so I made a couple of wrong turns before parking in front of what I assumed to be his house, the only one for miles. As I got out, a sinewy figure emerged from the darkness and shook my hand. “Hi. I’m John,” he said, in a butterscotch baritone. As he ushered me inside his modestly sprawling ranch house, I finally got a look at him. Dressed in jeans and running shoes, he sported a single earring and a tattoo that stretched halfway down his arm from beneath his white T-shirt. His deep suntan was set off against artfully mussed hair with frosted tips. He looked less like a 61-year-old millionaire tech icon than a rock-and-roll drummer who’d gotten lost on his way to the Sunset Strip.

His maverick style notwithstanding, McAfee started out in life along fairly conventional lines. As a kid he rode his bike, played with his dog, and fished in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. When it came time for college he went to a small regional school and picked up a degree in mathematics, which led to stints cubicle-jockeying as a programmer for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and then Xerox.

In the ’80s he was working for Lockheed when he came across one of the first computer viruses, the Pakistani Brain. McAfee devised a program to scan for such malicious code and, at a time when the software industry was obsessed with preventing customers from making unauthorized copies of its programs, started posting his software for free. It spread like wildfire. While individual users paid nothing, McAfee charged corporations $1 per computer for support. In that first year, McAfee and two employees grossed $10 million.

The company grew fast, but eventually McAfee became bored and sold off all his shares. (The company, which still bears his name, grossed $1 billion last year.) A few years later he started a new company, Tribal Voice, with a new idea: sending text messages over the Internet. Within three months he had four million users. McAfee sold the company in 1999 for $17 million.

While McAfee was riding up the escalator to wealth, he was simultaneously creating a life of unencumbered freedom. “Ever since I was 22, I’d work for a year, then take off and travel for a year,” he says. He has lived in New York City, Brazil, and Germany. He has traveled through Mexico, living in a van, buying stones and silver and having them made into jewelry to sell to tourists. Later, back in the States, he became infatuated with racing four-wheel ATVs (he has totaled 10 of them) and with making long-distance, open-ocean voyages on Jet Skis (he’s sunk nine).

He loved business, at least the startup part—“There’s no structure, no bureaucracy, just a group of people trying to do something magical,” he says—but by the time he sold Tribal Voice, he was done with the moneymaking hustle. “The goal of having enough money is irrational,” he says. “You think you’re free, but you’re not. You have obligations, responsibilities, worries, and cares. The more money you have, the less free you are. Look at the big yachts you see floating around. The bigger they are, the less their owners use them. Their kids, their friends, their business associates, sure—but not them. Success for me is, can you wake up in the morning and feel like a 12-year-old? You know, when you can go outside, see a strange kid, and say, ‘Hey, do you want to play?’ Can you get back to that?”

MY SECOND DAY IN Rodeo, a ferocious windstorm kicks up, with gusts up to 50 miles per hour. It would be too dangerous to fly, so in the afternoon McAfee shows me his collection of ATVs. Ten minutes later we’re roaring across the desert plain, dodging mesquite bushes. At a dry streambed, we work our way down its steep bank, and then roar along its narrow graveled bottom, leaving a rooster plume of dust in our wake. When we reach a sandstone escarpment, a short hike leads us to the remains of an ancient Indian settlement sheltering beneath an overhang. McAfee points out a petroglyph on the cliff and says it was probably painted some 2,000 years ago.

McAfee has long been fascinated by ancient sources of wisdom. After he sold Tribal Voice, he devoted himself full-time to yoga. He built practice rooms at several of his homes around the country, became a yoga instructor, and in 2000 wrote and published four books of yoga-flavored wisdom. But that phase is over. When I mention to him that I’ve bought his yoga books, he gestures dismissively. “They’re all trash,” he says. “That’s what was going on in my mind at the time. It was a transition point for me, from the world of business to a more open world.”

In fact, McAfee had become gripped by a new passion. In 2003 he was flying to Nepal with his girlfriend, Jennifer Irwin, when he opened the in-flight magazine to an article about a kind of lightweight airplane called a trike. Also known as a weight-shift ultralight, it’s essentially a hang glider with a 1200cc motor in back. About the same power and weight as a motorcycle, a trike provides a unique sense of speed (up to 95 miles per hour) and maneuverability—the same thrill as McAfee’s ATVs and Jet Skis, but in three dimensions.

Irwin remembers the moment vividly. “He showed me the article and said, ‘What do you think of this?’” She knew that the question was rhetorical. “My heart sank,” she says. As soon as the couple was back from the Himalayas, McAfee started making inquiries, and before long he had located a flight school near Phoenix.

While doing his flight training at Kemmeries Aviation in Peoria, Arizona, McAfee met an eccentric former guided-missile engineer named Neil Bungard. In the course of his own aerial adventures, Bungard had figured out how to navigate underneath Tucson’s heavily monitored airspace by flying low up the Santa Cruz River, beneath the radar of nearby Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. Intrigued, McAfee tagged along one evening as Bungard showed him the route. But when McAfee balked at slipping underneath a set of low-slung power lines and instead flew over them, he triggered the radar and wound up being intercepted by Air Force Black Hawk helicopters. “We came around the corner and there they were, with guns pointing at us,” he remembers.

McAfee managed to avoid being arrested, and a new obsession was born: shooting over the landscape at minimal altitude, sometimes so low that the yuccas whacked his undercarriage. Gunning through canyons became a particular favorite. The general rule of flying is that the higher you fly, the safer you are, but McAfee decided that low was the way to go. He even came up with a term for the practice: aerotrekking. He convinced a core group from the flight school to take up the new hobby, and together they formed an informal club, the Sky Gypsies. Several, including McAfee and Irwin, got tattoos of the new club’s symbol: stylized angel’s wings.

The idea had one major drawback. In all the vast, rugged expanse of the desert Southwest, there were few convenient places to land and refuel, to spend the night, to hangar the aircraft during storms. So McAfee decided to set up a network of stations. A day’s journey apart, the six ports are spread along a great smile-shaped arc that curves across some 800 miles of the roughest, most spectacular terrain in Arizona and New Mexico. In Rodeo, he created the most elaborate outpost of all, a complex that includes a coffee shop, an Internet lounge, an organic food market, a 35-seat movie theater, and four large air-conditioned hangars. For visitors, he bought 12 Airstream trailers on eBay and a dozen vintage cars to park alongside them for ambiance. Anyone who seriously wants to learn to fly is welcome to come and enjoy the facilities at a highly subsidized rate of $45 per night. “I’m not trying to turn a profit,” McAfee explains. “The purpose of this facility is to provide an environment where almost anyone who has the spirit of adventure can participate.”

IF YOU WANT TO ride with John McAfee, you’d better be ready to get up early. The knock on my door comes at 4:30 a.m., and by 6 a.m., with dawn breaking over the Peloncillo Mountains, the ragtag band is ready to taxi out to the 7,200-foot dirt runway. This early, the air is almost perfectly calm, perfect for smooth riding. After a few hours, the sun-baked desert will start spinning up big thermals like invisible tornadoes.

McAfee taxis out first, followed by Irwin; and then Bungard; John “Ole” Olson, a flight instructor; and Bruce Thompson, a retired geneticist. Jim Hunter, an electrical engineer, and Ivan Brauer, a general practitioner, bring up the rear. Within a few minutes we’re up in loose formation, like a flock of giant colorful butterflies, heading east into the rising sun. McAfee flies lower than most, scooting along the rolling valley floor at 20 feet, scattering jackrabbits and passing herds of bemused-looking Black Angus.

A few miles ahead, the broad sere valley bottoms out into a wide dry lakebed. The baked mud is flat, ideal for landing, but recent rains may have left its crust dangerously thin. It’s hard to tell from the air. McAfee makes a call on the radio. “Hey, Neil,” he says. “What do you think? Is it landable?” McAfee circles a hundred feet up, trying to eyeball the surface. While he’s mulling, Irwin swoops past, descending, and calls over the radio: “I think we can do it.” Her wing skims over the surface, and she touches down. She lets out a whoop: “It’s beautiful!”

McAfee is uncharacteristically quiet as he descends toward the lakebed. I know that, of all the perils of flying, none touches him more deeply than the possibility of Irwin’s getting hurt. Earlier, I’d asked him what was the hairiest moment he’d had while flying, and he said that it had been watching Irwin attempt a takeoff in strong winds. A gust had come from the side and nearly flipped her over. If her wingtips had caught on the ground, the crash could have been fatal.

McAfee’s fears are not idle. On his right arm, there’s a recently added teardrop below the tattoo of the Sky Gypsies symbol. Last November, McAfee’s nephew, Joel Bitow, was flying with a student from Rodeo to Bisbee, Arizona. Though just 22 years old with only 65 hours of piloting experience under his belt, Bitow showed considerable promise as a pilot and was heading up a local training program. Then, at 9:30 that morning, with clear skies, good visibility, and no obstructions in sight, Bitow flew into the side of a canyon. He and his passenger were both killed. McAfee thinks the passenger may have had a heart attack and fallen on the controls. Others suspect that Bitow’s flight experience simply proved inadequate amid the inherent dangers of flying low in unforgiving terrain. No one knows for sure.

If the accident brought home the potential for death, it did not dim McAfee’s enthusiasm: “When we’re aerotrekking, it’s [a line] between safety and danger. You can cross the line where you’re no longer in charge of your safety. Or you can ride the edge of fear in perfect safety.”

ONE DAY, I WAS hanging out in McAfee’s kitchen while he was in the next room, working on personal business. One of the Sky Gypsies wandered in from outside and started chatting with him. That kind of thing happens all the time; McAfee lives in an astonishingly open way, having welcomed into his life a more or less random group of men and women whose only real connection is a passion for flying. People and their dogs blow in and out continually. All are cheerfully welcomed, and McAfee always makes time to sit down and shoot the breeze.

I went in and joined the conversation, which somehow came around to the fact that I was due to be married in a few months’ time. McAfee asked if I wanted to have kids, and I said I thought I did. He said that he’d been through parenthood—he has one daughter, by an earlier marriage—and he’s over it. “Whatever fantasy you have about life after children, it’s going to be far worse,” he said. “You will have to sacrifice the thing that you hold dearest: your freedom.”

Maybe he’s right. Maybe putting on the halter of responsibility is a kind of betrayal of one’s true purpose. But I can’t help but wonder whether freedom doesn’t have its own price. Is it really possible to be entirely true to yourself without being irresponsible to others?

That day we took off from the dry lakebed, McAfee separated from the group and headed west, following the rising ground toward a ridgeline. Descending to a dry riverbed, he carved a series of S-turns above the steep banks, swooping over piles of rocks and dry gravel slopes. It was like running the streambed on the ATVs, but at four times the speed. He aimed for the crown of an ancient tree, then flicked the wing up and zoomed over the top.

Eventually, the streambed petered out, and we paralleled a smooth ridge. A quarter-mile farther, the ground fell away as we passed a sheer precipice, 1,000 feet high, a ragged tear in the earth between the mountains and the parched valley. My stomach was in my throat. McAfee banked gently to the right, following the hill’s undulation.

I asked him if he ever saw an end to this kind of flying for himself.

“The more I fly, the more exciting it becomes for me,” he said. “I’ll go off by myself, and if the wind blows south, I’ll go south. If I see a canyon, I’ll go into it. I fly by feel. I don’t need to look at the dials. You develop a sixth sense about the plane and its condition. You reach a point where you become a part of the plane.”

I pointed out that he’d had passions before, and he’d wound up leaving them behind. Who was to say that wouldn’t happen again?

“I anticipate that happening. It doesn’t worry me at all.”

“So,” I pressed, “what do you think you’ll be doing in five years?”

“I don’t have a clue,” he said. “That’s how I like to live.”

This article originally appeared in ���ϳԹ��� Go‘s Fall 2007 issue.