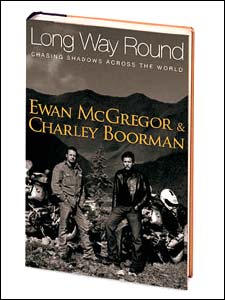

When Scottish actor Ewan McGregor (Big Fish, Star Wars: Attack of the Clones) set out for New York last April, he opted to take the scenic route. He and a friend, British actor Charley Boorman, left London on BMW GS R1150 ���ϳԹ��� motorcycles and rode east for 108 days, crossing Europe, Central Asia, Siberia, Alaska, Canada, and the Midwest. On July 29, after almost 20,000 miles, the duo pulled into Manhattan, trailed by a convoy of 50 fans on motorbikes. They recount the journey in (Atria Books, $26), on sale November 2, and in a six-part television documentary airing October 28 through December 2, on Bravo. Shortly after the weary riders dismounted, PATRICK SYMMES cornered them in the Mercer Hotel, where, sunburned and bearded, they demolished a bread basket to its crumbs.

ewan mcgregor long way round

OUTSIDE: All right, rat on each other.

McGregor: There’s not a lot of that.

You just spent three months together and you still get along?

M: Yeah.

BOORMAN: Ewan is the brother I always wanted as a kid.

Now that you’ve ridden all the way around the planet, how big is it?

M: It’s too early to say. Initially, you think the world is going to shrink. The first couple of weeks take you right across the Second World War. It makes you wonder. You think, Jesus, in the forties this was a disaster zone, a mess. And how easily we rode across it in a couple of weeks! Then things start to broaden out. You get to Kazakhstan, which is an enormous country, but still you’re crossing it in three weeks. I don’t know if it feels like a big world or a small world. The strongest impression I have, at the moment, is that people along the way are 99 percent of the time incredibly interested, friendly, helpful, reliable, trustworthy.

Any screwups?

M: We had far too much stuff: two of everything—two full tool kits, two gas stoves, two water purifiers. We had cameras mounted on our helmets, and we had walkie-talkie systems, and phone cradles for our mobiles. By the time we got to Russia, all of it had broken—rattled to pieces. We pared down so we had only one of everything. And we got rid of a lot of clothes.

B: At some point you realize that . . . this “necessity”—you really don’t need it.

What were your toughest times?

M: The first few days in Mongolia were unbelievably difficult. We’d look at a map, and Ulan Bator was still a thousand miles away. We just couldn’t get any closer.

B: We were riding for 18 hours a day and only achieving sometimes 20 or 30 miles. You’d have punishing days and not get anywhere.

I take it the dirt roads gave you a beating.

M: When you had to stand up on the pegs all day, you got jelly legs.

How about wind and rain?

B: In Mongolia, I don’t think we got fast enough to feel any wind. Getting into fourth gear was a revelation.

M: We had some hellish days in Kazakhstan. You were resisting the wind with your head at 45 degrees and would end up with terrible pains down your back, as if someone was pushing your head all day. That was tough. But over the trip, cumulatively we spent less than a day in the rain. Unbelievable.

If you could go back to one place, what would it be?

BOTH: Mongolia!

Any crashes?

M: A lot. I was rear-ended about 60 miles north of Calgary. I suddenly heard a screech of tires, and bang! Luckily, the front end of the bike lifted up, then back down. We had a bit of a wobble around and then came to a stop. A very close call.

What about a transcendent moment?

M: In Kazakhstan. It was the most perfect evening to ride. The temperature was absolutely beautiful, and the sun was just hanging there in the lower part of the sky. I got this complete sense of, This is where I was meant to be at this moment. I belonged on the back of the bike, on this trip. It was absolutely what I should be doing at this moment. Everything was fine at home. Everything was good on the road. I was struck by that feeling of complete contentment. Quite unusual.

I understand that you consulted a nutritionist and were going to live on organic lentils and fish that you caught along the route. How’d that work out?

M: Never caught a fish the whole journey. Not one.

Lentils?

M: Never opened. I left them in Siberia.