CHARRIS FORD is a perpetual parade float. In his black, convertible 1980 International Scout, he drives up and down the main drag of the absurdly picturesque town of Telluride, Colorado, where the San Juans’ jagged granite peaks rise up on three sides in curtains of pine, rock, and snow. He smiles, he waves, he catcalls to his many well-wishers. The cross section of Telluridians out and about today—some of them skateboarding, some rolling sport-utility baby carriages, many lounging on the benches outside the Steaming Bean coffee shop—all look unhurried, well caffeinated, and fit.

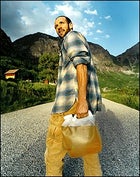

Charris Ford cruises Telluride with his fuel of the future: used French-fry oil.

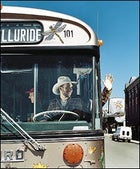

Charris Ford cruises Telluride with his fuel of the future: used French-fry oil. Top Rod: Ford powers Telluride’s biodiesel bus down Main Street.

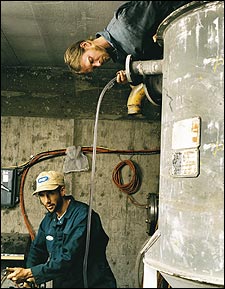

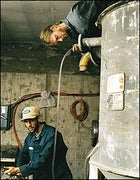

Top Rod: Ford powers Telluride’s biodiesel bus down Main Street. Slippery Hope: biodiesel entrepreneur Charris Ford (bottom), with colleague Nickolai Cowell, at work in their Colorado warehouse

Slippery Hope: biodiesel entrepreneur Charris Ford (bottom), with colleague Nickolai Cowell, at work in their Colorado warehouse

“Hey, you’uns, whassup?” whoops Charris.

They respond with wolf howls and fist pumps. In a few minutes he’ll pass them going the other direction. They’ll raise their coffee mugs in salute. To them, 33-year-old Charris (pronounced “Char-iss”) represents everything they love about their own well-ordered and enlightened place in the universe. He is youthful, good-looking, hip, and eminently politically correct. He is well connected, with friends in Hollywood, at newspapers, and in politics. He raps and sometimes speaks in iambic pentameter. He cooks ostrich eggs. He talks on a cell phone while sitting on a composting toilet. And he has brought biodiesel to Telluride. A concoction of vegetable oil, lye, and alcohol, biodiesel can supplant standard petroleum diesel. (The lye reacts with the oil, leaving glycerine as a by-product and methyl esters as fuel.) Thanks to Charris’s vision of a world powered by processed veggie grease, a handful of locals now use the stuff in snowcats, tractors, backhoes, generators, school buses, golf-course maintenance vehicles, and a construction crane. And, of course, Charris’s Scout runs on the green-friendly fuel. A dozen restaurants currently hand over their spent cooking oil to Charris and his band of biodiesel confederates, and more are ready to sign up when the fuel-brewing capacity of his company—Grassolean Solutions—increases. Although communities like Breckenridge have launched transportation fleets powered by “B20,” a relatively timid blend of bio and petroleum diesel, Telluride has become the first town to run a public bus on “B100,” a mixture as pure as biodiesel gets.

The thin air smells like a fried spud.

CHARRIS’S KETCHUP air freshener sways in the breeze. He launches into a rap he will perform at the Mountainfilm festival. He pounds out a beat on his wheel and spits Bobby McFerrin-style bass notes: “KA-doon-doon-WHACK! We could get driven to extinction just for spinning our wheels / Up an’ offin’ ourselves with our own automobiles… You see, I need a vehicle to meet my vehicle needs / You know, for carryin’ loads, you know, to travel at speeds / I got that veggie fuel burnin’, now I’m rollin’ with ease / Is that the scent of French fries I’m smellin’ on the breeze?”

Charris began writing raps in high school, in St. Petersburg, Florida, and then sang them in his head during a decade spent on his family’s organic farm, in the backwoods of Tennessee. A Woodstock-era baby, Charris was conceived right after his mother’s last acid trip. He says his name comes from charisma and a type of Indian hashish. His father, once a Madison Avenue ad exec, dropped out to experience the sixties, moving the family to Haight-Ashbury and then to a remote Colorado cabin. “I was a handmade-Jesus-slipper-wearing kid,” says Charris.

But now Charris has very, very big plans. He wants to start a national chain of Grassolean stations that sell everything from biodiesel to organic candy bars. “I have dreams of becoming the Steve Jobs of green energy,” he says. Currently he’s making do with his plant, a bunch of metal drums and a ramshackle building in nearby Montrose, where Grassolean Solutions produces about 100 gallons of biodiesel a week for its own use. Within a year, Charris and his team of investors and workers—which includes a local dentist, an eco-contractor, and a recent Harvard grad who mixes the potent grease-lye-alcohol cocktail in coveralls and a Dr. Seuss hat—plan to produce more than 6,000 gallons a week. They’re pursuing a petroleum distribution license from the state of Colorado so they can officially sell their product to the public and to their beloved city bus, the Galloping Goose. (Although Charris is the one who convinced the local government to convert the Goose to veggie fuel, the U.S. Department of Energy is underwriting Telluride’s high-altitude transit experiment and requires the town to buy its biodiesel from a legit supplier in Denver.)

Charris is gambling that we are approaching biodiesel’s Big Moment. He may be right: Germany has more than 1,000 biodiesel stations, and in Austria, McDonald’s happily hands over its grease. In the United States, some 12 companies manufacture about 20 million gallons of the stuff annually, mostly from virgin crops like soy. From California to New York, there are about 100 biodiesel stations, which mainly service small commercial fleets. (There is no conversion necessary for existing diesel engines, except that when using pure biodiesel in cold climates, you might want to heat the fuel line to avoid having your grease turn into Jell-O.) Less than 2 percent of cars in the U.S. have diesel engines, but that could change, given their enviable fuel efficiency. Though U.S. automakers have explored biodiesel as a future wonder fuel, for now most are focusing on the long-range promise of fuel-cell and hybrid technology.

In the meantime, petroleum diesel contributes to some acute respiratory problems. One of the dirtiest fuels, it emits polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are carcinogenic, as well as carbon dioxide, arsenic, sulfur, benzene, and formaldehyde. Biodiesel exhaust, by contrast, is almost as pure as mountain air. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency—which recently ordered strict sulfur-emissions standards for diesel big rigs—has found that veggie fuel cuts particulates and carbon monoxide emissions by more than 40 percent and hydrocarbons by 67 percent.

It all goes back to Rudolf Diesel, really. When the German mechanical engineer unveiled his efficient engine, in Paris in 1900, he intended it to run on peanut oil and envisioned a world of farmers growing their own regional fuel. This is the scene Charris wants to construct in Telluride—except, in this case, the oil has played host to a dead chicken wing.

MEANWHILE, WHERE’S the famous veggie bus? “It’s gotta be around here somewhere!” Charris yells, weaving his truck through the throng of film-festival patrons.

“So we’re driving my truck all over town in order to chase the public bus,” he laughs, drumming his hands on the steering wheel. “How many potatoes had to die for this trip?”

Utopia and reality crash in other ways. The Scout’s fuel heater is on the fritz, and occasionally the truck belches gray smoke. “This is not the look I’m going for,” Charris says.

The Granola Ayatollah of Canola tells me he first landed in Telluride for a mushroom festival five years ago. He and his wife, Dulcie Clarkson, are caretakers on a ranch. To the paleohippies who now hold positions of power in local government, neocapitalist hippies like Charris signal the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. As Art Goodtimes, a Green Party county-commissioner-cum-poet, told me, “Telluride is really receptive to the 22nd century, so we put money into the individual visions of crazy people.”

It didn’t take long for the bearded rapper and his rig to attract attention. He starred in one of last year’s film-fest hits, a documentary titled French Fries to Go, which showed in 80 venues across the country. And he will appear in another documentary (this one on the Galloping Goose experiment), financed by an Energy Department grant. Charris counts celebrities Daryl Hannah, Dennis Weaver, Val Kilmer, and doctor/guru Andrew Weil among the friends on his biowagon. “I love driving around in his veggiemobile,” says Weil, who met Charris at one of Telluride’s ‘shroom festivals.

“Charris has expanded a lot of people’s horizons,” affirms Hannah. “I am definitely buying a biodiesel truck just like his to use in L.A.”

Finally, we spot the multicolored Galloping Goose picking up a load of Mexican service workers on the edge of town. Charris screeches to a stop and we jump on. The driver, Himay Palmer, sports navel-length blond dreadlocks and a floppy canvas hat. He loves driving the veggie bus, he says, because it makes people smile. Palmer is beaming. Charris is beaming.

But it may take a while for the aroma of cooked grease to waft over flatland America. “It’s too early to write off petroleum,” says David Lax, a senior environmental scientist at the American Petroleum Institute. Lax is quick to point out biodiesel’s deficiencies, including cost (anywhere from 20 cents to a dollar more per gallon than petroleum), bacteria growth, and its tendency to corrode rubber gaskets and hoses. There are also supply and distribution problems.

“Biodiesel could contribute 5 percent of our diesel needs,” counters K. Shaine Tyson, project manager of the Colorado-based National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s diesel project. “There are real benefits that would diversify our energy supply, make us less dependent on foreign oil, reduce trade deficit, and improve the U.S. economy. It’s a step in the right direction.” If biodiesel and other alternative fuels contributed just 4 percent of our fuel needs, we could subtract 146 million barrels of imported crude annually. It sounds good, but Tyson concedes that this day is a long way off, unless the government, or popular sentiment, persuades more drivers to convert.

This is where Charris hopes to come in. “What we’re trying to do with biodiesel is give people an experience,” he says. “How can I inspire my generation to turn around their materialist notion of cool and make things that our survival depends on cool? I see biodiesel like the sixties sexual revolution, where people can have an experience and their minds are catching fire.”

So biodiesel is like sex? Well, yeah. Says Charris, “It’s not subtle, it excites your friends and neighbors, and it’s fun!”