WILL MACKENZIE IS LINING UP an eight-foot birdie putt halfway through the first round of the Zurich Classic, a low-key April tournament held in New Orleans the week after the Masters. Per PGA regulations, he has the form-fitting, deep-pink polo shirt from his Swedish clothing sponsor, J. Lindeberg, tucked neatly into his gray slacks, and a white golf hat from Bridgestone holding back his thick, sun-bleached brown hair. The 32-year-old buries the putt to quiet applause from the handful of spectators fanning themselves in the Louisiana heat, grabs his ball, and slowly walks off to the next tee. Standard uniform, standard procedure. In other words, if you were to find yourself watching Will “Willy Mac” MacKenzie play golf on a Sunday afternoon, you might think, This is the most unusual player on the PGA Tour? But dig just a little┬Śscratch the surface, really┬Śand the picture gets much scruffier.

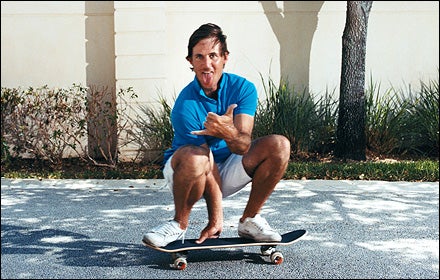

Will MacKenzie

Start by looking at MacKenzie’s player profile on the official PGA Web site. His stats this past June won’t tell you much┬Śhis standing on the money list (58th), his rank among players in scoring average (53rd), his tournament victories (one, the 2006 Reno Open)┬Śbut the first of the two photos in his “player gallery” will provide a clue. Rather than a shot of MacKenzie playing golf, you see him backstage with hip-hop stars the Black Eyed Peas (that’s him in the blue blazer, one spot away from Fergie). Now scour the news reports about January’s season-opening Mercedes-Benz Championship in Hawaii. MacKenzie took fourth place and earned a $260,000 paycheck. But while his competitors logged extra time on the practice tee, MacKenzie spent his time between rounds surfing. At a break called Shitty’s. “Hey, man, I was getting my work done,” he’ll tell you. “But I’m not going to Hawaii and not surfing.”

Finally, search “Will MacKenzie” on Wikipedia. Here’s what you’ll find:

MacKenzie was born and raised in Greenville, North Carolina. He was a golfing prodigy growing up but burned out on golf at age 14 and completely quit the game after high school. He then spent five years snowboarding, kayaking, and climbing rocks while living out of a van in Montana. At one point, he spent 30 days in Alaska without showering, smoking blunts every day, living in a cave, and ending up with frostbite … A glimpse on television of his boyhood idol, Payne Stewart, winning the 1999 U.S. Open rekindled his love affair with the game, and he decided to play professionally. He turned pro in 2000.

All of which is true. Well, most of it, anyway.

FOR THE RECORD, Will MacKenzie actually quit playing golf after tenth grade, though this isn’t the point in his bio with which hereally takes issue. “I don’t know where they’re getting the smoking-blunts-in-the-cave part,” he says. “Yeah, I think I smoked, but let’s say I never inhaled.”

It’s 7:30 in the morning, and MacKenzie is eating breakfast at a posh New Orleans hotel before his first-round tee time. Next to him sits his 24-year-old girlfriend, Alli Spencer, a recent college graduate who models for the likes of Guess and FHM and is wearing a tight white T-shirt that reads LITTLE MISS TROUBLE. MacKenzie starts talking as soon as he sits down. By the time the coffee arrives, he’s covered burritos (a favorite), professional climber Chris Sharma (a hero), and fishing (a passion), though somehow it doesn’t seem all that scattered. MacKenzie’s sanguine, raised-in-the-sun manner and North Carolina drawl dampen his rapid-fire brospeak, and he moves with an athletic grace┬Śhe’s five-eleven and broad-shouldered, a sinewy 170 pounds┬Śthat masks his inability to sit still.

Even when he talks about his personal history┬Śwhich he’s been reciting almost weekly since Hawaii, when golf writers finally stumbled upon their new John Daly┬Śhe manages to be relaxed yet frenetic. He talks about growing up in an athletic family, the third of four boys; picking up golf at age four, when his oldest brother, ten years his senior, sawed off a driver, five-iron, and putter and began taking him to the local course; winning his first tournament, the Popsicle Open in Greenville, at age five; becoming a fixture on the national junior scene; burning out at age 14; and being a standout soccer and football player in high school.

Spencer, who has been happily clarifying (and poking fun at) MacKenzie, elaborates. “According to Will, he could pretty much be a pro in anything,” she says.

“Definitely motocross,” he says. “There’s no doubt, dude.”

Whether he was pro material or not, MacKenzie was an all-state kicker on the football team, capable of 60-yard field goals, and schools were lining up to recruit him. “Except for that 1.8 GPA,” he says. “And the 940 I got on my SAT didn’t really help.”

“You did not make a 940!” Spencer interjects.

“A 940 was great back in the day,” says MacKenzie. “It used to be tough.”

“It was not great ever. It’s awful. That’s like …”

“Retarded?” MacKenzie offers.

“Yes, retarded.”

“So I didn’t get any offers. They all wanted me to kick football for them pretty bad. But they were like, ‘This 1.8, bud┬Śwe can’t get you on scholarship.’ ” And so in 1993, after a semester stint at a local college, MacKenzie took the money he’d saved up washing dishes and selling grilled-cheese sandwiches at Grateful Dead shows and headed west, kicking off his strange odyssey to the PGA Tour. Only later, when he was 25 and diagnosed with ADD, did he have an explanation for his academic struggles. But in a house with four active boys and endless outdoor options, the line between having ADD and keeping up with three brothers can get a little blurry. “I know it’s overdiagnosed,” says Spencer, “but Will has it. We were at lunch once with a financial adviser, going over a bunch of serious stuff. I look over at Will and he’s got the menu open on his head, like a hat, and he’s drumming with his silverware and staring out the window.”

Willy Mac doesn’t medicate┬Śmight mess with his game.

LATER THAT DAY, MacKenzie bounds up to the first tee with a round of “Hey, bros” for his partners, Eric Axley and Chris Smith. Like any serious golfer, he takes his time lining up his shots. He sprinkles grass blades to check the wind, settles his feet, steps back and repeats the process. But once he strikes his ball, he’s back to being Willy Mac: shouting hello to a player on the next fairway over, flipping Spencer the bird and then quickly blowing her a “just kidding” kiss, giving me the classic bro shake after sinking a putt.

“I just think of it as snowboarding out there,” he says. “Right to left, left to right. I try to envision the grass like a sea of fresh powder, and I’m going to point it into that beautiful wind lip and make one huge heel-side turn. That’s how I work the golf course. But then I space out between shots. If I had to just dwell on golf the whole time, I’d really go psycho.”

When MacKenzie first left North Carolina in his white 1986 Toyota minivan, he had no particular plan. He simply drove to the Rockies and began resort hopping. His first stop, Taos, New Mexico, seemed nice but didn’t allow snowboarding (“See ya, Taos”). He continued on to Telluride, Colorado (“OK”), Crested Butte (“Hmmm, nice”), the resorts in Summit County (“Nah, this place is lame”), Steamboat (“Wasn’t steep enough”), and Utah (“The vibe was just sort of dicey there”). He stayed in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for a while, but mostly because he ran out of money and had to work at a Taco Bell (“Giving burritos to all the kids”). Finally, a month after leaving Greenville, he pulled into Big Sky, Montana (“Goddamn, this place is heaven”), parked his van in an empty corner of the ski-area parking lot, and unfurled his zero-degree bag.

“It wasn’t unheard of for people to sleep in their cars there, especially in summer,” recalls Jason Frounfelker, who worked with MacKenzie at Big Sky until MacKenzie got fired for showing up late. “But he was a rare breed in those winters. And he was a dirtbag. Tried to work whatever angles he could.”

MacKenzie proudly claims that he was on his way to becoming Dirtbag King, a title bestowed upon the crustiest local every season. “You have to be a little older,” he admits. “But I was already kind of legendary for having a couple of seasons when I didn’t have a pass but still did like 100 days by poaching in the lift lines.”

In the warmer months, he became a Class V kayaker and soon had work as a raft guide, following the spring and summer flows from Montana’s Gallatin River to West Virginia’s Gauley and, eventually, to the rivers back in North Carolina. At one point, he had to duct-tape padding onto his heels so he could paddle the day after a 15-foot rock-climbing fall. “We used to call Will our migrant worker,” his mother recalls. “The snows would melt in Montana and he’d start heading south.”

But one year he altered his orbit. In 1998 MacKenzie saved enough money to drive to Alaska, though not enough for lift tickets or lodging, let alone the helicopter rides he was after. So he built a snow cave outside Valdez, fired up his gas stove, and hoped for the best.

“I was hitching one day and this van picks me up,” he says. It was pro snowboarders Noah Salasnek, Mike Devenport, and Johan Oloffson, who were in Alaska shooting with Standard Films director Mike Hatchett. “They gave me a ride back, and I broke down and said, ‘Look, fellas, I came here to ride something sick. Is there some way I can get in y’all’s group for one mission?’ “

“We felt kind of sorry for him at first,” recalls Hatchett, who ended up taking MacKenzie into the Chugach several times over the next three weeks. “But all the pros were stoked on him, because he was a really good rider and totally cool to hang out with. That’s the only time we’ve ever taken anyone up for free.”

MacKenzie still refers to Alaska as the best trip he’s ever taken, both for the riding and for the career turning point it would prove to be┬Śafter five seasons, he decided not to return to Big Sky for another winter. Instead he moved back home, making enough cash selling Christmas trees to fund a three-month surfing trip to Costa Rica. There he met a tourist from California who said he’d made a fortune importing stretchy Costa Rican hammocks into the U.S. Three months later, MacKenzie had gone broke trying to sell them door to door in North Carolina, home to Hatteras Hammocks, the largest hammock company in the world.

“That didn’t work out so well,” he recalls, chuckling. “I was having an early midlife crisis, like, Am I going to be a dirtbag forever?”

HOLLYWOOD LOVES A GOOD sports comeback. There are already discussions about who will play Lance Armstrong on the big screen. But with no life-threatening illnesses, no legal troubles or noble sacrifices, Will MacKenzie’s return to golf doesn’t exactly lend itself to dramatic treatment. Just an unemployed ski bum living with his parents, pondering his next move.

It was a Sunday afternoon in June 1999 and MacKenzie was watching with his father as Payne Stewart emerged from a four-man tie with Tiger Woods, Phil Mickelson, and Vijay Singh to win the U.S. Open at North Carolina’s Pinehurst Golf Club. MacKenzie had played the course as a young star, and Stewart had always been his favorite player. “It was epic, and it was in N.C., and the stars aligned,” MacKenzie says. “That U.S. Open is the only reason I’m playing golf now. I realized that I was really good at a lot of things, and I wanted to be great at something.”

Call it dumb luck or divine intervention, but that afternoon changed the course of his life. “It’s kinda scary now that I think about it,” MacKenzie admits. He convinced his parents to help fund his venture, called in favors from old golf coaches and local pros, and was soon spending 12 hours a day working on his game. By the following year he was competing on the mini-tours┬Śgolf’s version of the minors┬Śscraping together entry fees and, yes, sleeping in a van.

He rose quickly, playing his way onto the Canadian Tour and then earning player-of-the-year honors on the NGA Hooters Pro Golf Tour in 2004, the last stop before the PGA. Later that year, MacKenzie earned his Tour card at Q school, the annual ten-round marathon where more than 1,000 players compete for just 30 PGA spots. To keep it, however, he needed to finish the next season with a tournament win or in the top 125 on the money list. He didn’t come close. But unlike most pros, who can spend several years trying to earn a spot back on the Tour, MacKenzie bounced back immediately and survived his second-straight Q school in a row. “It’s a tremendous feat,” says Olin Browne, a 15-year pro who’s been to Q school 12 times and missed his card by one stroke on three separate occasions. “It’s so stressful, I can’t even watch it on TV. But Will just has a different air about him.”

That grace under pressure is evident during MacKenzie’s opening round in New Orleans, in which he overcomes three bogeys and one triple bogey with six birdies to finish at even par. It’s typical MacKenzie: all over the place, but it works out. The next day I watch him rebound with a more consistent three-under 69, good enough to make the cut by two strokes. He’ll go on to finish the tournament in a tie for 28th and net $37,210┬Śmiddle-of-the-pack respectability that should keep him comfortably in the PGA ranks. His peers┬Śand the media┬Śwould welcome that. “I’ve never heard anyone say anything even close to bad about him,” says Charley Hoffman, a PGA pro from San Diego who’s bonded with MacKenzie over their love for the ocean. “He’s all business on the course, but in the clubhouse he’s cracking jokes, having fun with everyone. He’s just his own breed, and people respond to that.”

It was in Hawaii this year that MacKenzie’s legend started to take shape, beginning with his breakdancing performance at a New Year’s Eve party that kicked off the Mercedes-Benz Championship. “Once the spirit gets in me,” he says, “I have to start.” And when an interviewer for the Golf Channel asked if he was still sleeping in his van, MacKenzie gushed that he was staying at the Ritz-Carlton, offering up his room number as proof. He had to unplug his phone for the rest of the tournament so he could sleep.

THIS PAST WINTER, MacKenzie went back to Montana to snowboard for the first time since 1998. He can still feel the rotator cuff he injured once while kayaking and, courtesy of the Alaskan cave, still has limited feeling in two toes on his left foot. Which is why he now limits his non-golf pursuits mostly to surfing and taking his fishing boat out in the waters around his new home in Jupiter, Florida. “Look at Chris Sharma,” he says, pointing to the climber as an example of single-minded athletic excellence. “I’m sure he could kill it on a mountain bike if he wanted, but he’s not trying to. He’s pulling rock 24/7. That’s how I have to be with golf. It was either go back to guiding for the rest of my life and try not to drown the customers or really put everything into this.”

MacKenzie accepts that, until his game trumps his backstory, he will always be covered the same way: Tiger Woods shoots a 70; Phil Mickelson shoots a 70; Will MacKenzie┬Śa free spirit who quit the game and lived in a van and slept in an ice cave for a month without showering┬Śshoots a 70. “I don’t care,” he says. “In my mind, that’s all something I did, and I’m happy I did it. But now I just want to be a great golfer. I understand it, though. They’ve got to have a story.” And they do.