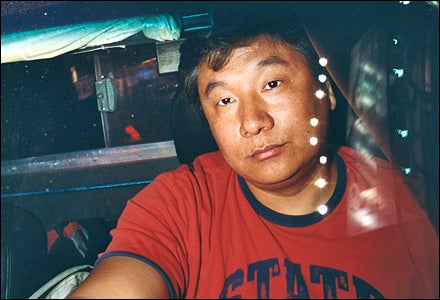

ON A CLEAR SPRING DAY in New York, Tsering Norbu Sherpa—former Himalayan guide, father, pop-music fan, oenophile, and independent taxi operator #2B35—was hauling ass through the streets of SoHo.

His left arm draped out the window, Tsering dodged shoppers, pointed out a Dustin Hoffman look-alike, ogled a Segway rider (“Wow, cool”), admired a set of Tibetan prayer flags (“We call them wind horses, you know”), and offhandedly listed the nightclubs he counts on for late-night passengers (“Pangaea, Lotus, Bungalow 8 …”). Cruising past the lunch crowd at Felix, on West Broadway (“Looks like a beehive!”), he catalogued his tastes in rock (Nazareth, Bad Company), country (Hank Williams Jr.), and wine (Chilean cabernet, Oregon pinot).

Tsering was in a talkative mood. “These are different kind of mountains,” he joked as we rolled uptown. “Building is good, but can’t climb them!”

“To me, climbing mountains and driving taxi is pretty much the same,” he went on. “They both have risk. You respect the mountains, you have less casualties. In the taxi, you must respect the flow. Otherwise you are going to get hit by some crazy drunk New Jersey driver.”

Tsering moved to New York in 1998 from Darjeeling, India, with his wife, Nima. A decade later, he seems right at home in the city, dressed with just enough urban attitude—camo pants, Gap sweatshirt, Skyy Vodka T-shirt—to look the part, Brooklyn style. Like most Sherpas, Tsering is a devout Buddhist, and behind the wheel he exhibits the blithe self-possession of a man at peace. He drives like an old hand, which is to say, at high velocity. But he skips the NASCAR tactics, uses his turn signals faithfully, and handles his cab—a 2003 Ford Crown Victoria that he owns—as if it were a brand-new Lexus. He speaks to passengers in four languages (Urdu, Nepali, Hindi, and English), shrugs off bad tips, and infallibly delivers his fares to the correct side of the street.

Near Central Park West, we picked up a blond, pointy-shoed power-luncher headed uptown. Spying Tsering’s ID card on the cab’s Plexiglas divider, she poked her head through the window between us. Um, she wanted to know, was he really a Sherpa?

Yes, Tsering replied, his expression stoic. “Wow!” she said, slumping back, trying to think of what to say next. Tsering is incredibly humble; he didn’t mention his former job with the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, back in Darjeeling, training Indian soldiers for tours of duty in places like the 21,000-foot Siachen Glacier—on the disputed boundary between India and Pakistan—or the fact that his circle of friends and family includes dozens of elite alpinists.

The woman leaned in again. “I’m assuming you’ve climbed Everest,” she deadpanned. He hasn’t. Only a fraction of Sherpas have climbed the peak, though the image of Everest all but defines them in Western eyes.

Tsering is used to the question. Getting typecast as a loyal sirdar is low on his list of passenger annoyances—nothing like the time a man threatened to report him “to immigration” because Tsering asked him not to smoke. (He’s in the U.S. legally, on a renewable employment permit, and his green-card paperwork is in the pipeline.) It takes a lot to get Tsering riled. Marauding buses, jaywalking tourists—nothing seems to faze him. Nothing, perhaps, except the mountains he left behind.

I FIRST MET TSERING in 2003. Walking around one night with a friend who specializes in finding ultra-obscure ethnic restaurants, I was doubtful we’d spot one here on SoHo’s chic Crosby Street. But then he dragged me up a couple of steps into a windowless place not much bigger than a walk-in closet. The aromas of curry and black tea enveloped us. Ten or 12 men had formed a line, more like a scrum, craning and peering over one another’s shoulders. The place had a small sign that read LAHORE and a menu featuring pakoras, goat biryani, and other Central Asian comfort food.

My buddy and I were talking about mountains we wanted to see one day—K2, Everest—when we heard a quiet voice behind us.

“You guys climbers?”

We turned. Compact and sturdy, the man wore a battered Casio altimeter watch and black jeans. He had high cheekbones and dark, imploring eyes.

“I overheard you talking,” he said politely. “I am Sherpa.” He pronounced the e like a long a and gave a slight roll to the r: share-pa. “I worked as a trekking guide. I moved here five, six years ago. My name is Tsering.”

“All the cabdrivers come here,” Tsering told us as we ate samosas by the counter. Kazakh, Bangladeshi, Kashmiri, Ladakhi—they drink high-octane tea, hit the restroom, and stock up on sweet cakes and lentils before heading back into the maelstrom of New York by night.

“So … you know of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, right?” Tsering asked as we got up to leave.

“Yeah, of course,” we said.

“Tenzing Norgay was my grandfather.”

It was surprising enough that a grandson of Tenzing Norgay, the legendary Sherpa who conquered Everest with Sir Edmund Hillary in 1953, was driving a cab in New York. But Tsering went on to tell us that there were perhaps a hundred Sherpas working as cabbies in the city, many of them former guides.

Their presence, I learned, was part of a larger diaspora. Though roughly 150,000 Sherpas still live in Nepal, northern India, and Bhutan, perhaps more than 5,000 have left—heading to England, Australia, and Germany (where one, Ang Jangbu Sherpa, flies a Boeing 767), but mostly to America. Over the past decade Sherpas have been streaming to the U.S.—to San Francisco, Seattle, Salt Lake City, Portland, Oregon, Washington, D.C., and above all New York. The city’s Sherpa community has become the largest outside of the Himalayas, with around 2,500 members, most employed legally through yearlong work visas, harder-to-get green cards, or rare lottery visas, 50,000 of which are awarded randomly to applicants from developing countries each year.

Tsering’s wife, 36-year-old Nima Phuti Sherpa, is a former trekking guide. His close friend Ang Galgen Sherpa, 35, once had his own trekking company, Sherpa Expedition, in Kathmandu; now he drives a cab. Dawa Sherpa, a 45-year-old who has worked on expeditions up 26,906-foot Cho Oyu, is a cabbie, too. Three-time Everest summiter Kipa Sherpa sells jewelry from a stall on Canal Street, while “Speed Kaji” Sherpa (five times up Everest; six 8,000-meter peaks; one Guinness world record for fastest Everest ascent, since topped) moves furniture in Queens. Pasang Namgyal Sherpa, a 57-year-old mountaineering veteran, works for Landmark Wines, in Chelsea, with his brother, Temba, also a former guide. Their sister, Nima Diki Lama, runs a popular Himalayan restaurant, the Yak, in Jackson Heights, Queens.

None of those Sherpas still guides, but others living around the U.S. have kept a foot in the business. Tashi Gyalzen Sherpa, another of Tsering’s friends, runs a small travel agency in Queens called Himalayan ���ϳԹ���s. In Salt Lake City, Apa Sherpa—who completed his 17th Everest summit last May as part of the two-man SuperSherpas expedition—cofounded the Karma Outdoor Clothing Co. His climbing partner and fellow Utah resident Lhakpa Gelu Sherpa, a 13-time summiter, currently holds the speed record from Base Camp to the top (10:56:46). Last winter, Lhakpa ran the coffee stand, Peak Java, atop Snowbird ski resort.

But why would a Sherpa leave the kingdom of yaks and stupas for Super Size Me America? For some, like Nuru Lama Sherpa, who worked at Goldman Sachs after graduating from Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, it’s because of the educational opportunities. For most, it’s politics and economics. A distinct ethnic group that migrated 500 years ago from Tibet into Nepal’s Solu Khumbu Valley, the Sherpas spent centuries working as traders and raising livestock, but over the past 100 years they’ve become famous worldwide for their work as porters and guides on almost every Himalayan expedition ever launched. Mountaineering was never a sufficient economic base for all Sherpas, though, and in the past 17 years political turmoil has racked their homeland.

First, the Marxist-flavored People’s Movement, which emerged in Nepal in 1990, wrested away some of the power held by Nepal’s Hindu monarchy. Amid the discord, the charismatic Maoist leader Prachanda carved out a heavily armed following; up until a cease-fire was called in May 2006, some 13,000 Nepalis were killed in bombings, raids, and skirmishes between government forces and the Maoist rebels.

Combine that with a sharp drop in Western tourism to the region after September 11 and the situation for many Sherpas has become precarious. A top mountaineering Sherpa can earn around $3,000 or $4,000 per expedition, working two trips a year if he’s lucky. But that pales in comparison with the kind of money Sherpas can make here, some of them earning enough to send thousands of dollars home every year, according to the United Sherpa Association of New York. And they don’t have to worry about getting crushed by a falling serac.

Bob Peirce, an 83-year-old former trekking guide from Portland, Oregon, has helped a number of Tibetan and Sherpa newcomers get settled in the U.S. “Even the Sherpas here say it: It’s a migration,” he says. “The main reason they come—and they talk about this—is to make money. Working in a restaurant or a convenience store is probably more reliable than trekking jobs.”

Some observers, including Sir Edmund Hillary himself, see clear dangers in the trend. “I know a lot of Sherpas are now based in New York, and that’s fine,” says the 87-year-old, “but I just hope that they don’t completely lose their culture.”

“Going to work somewhere in New York, or anywhere in the U.S., would be very, very tempting,” Hillary says. “The only thing is, for every Sherpa who goes to New York and earns money and sends it home, the vast number are good people who are really needed in the Khumbu. I’d certainly hope that they all come home, because they have so much to give to their own communities.”

Tsering feels those losses but says he had to make the change. “I miss mountains and I love mountains,” he told me. “But what I don’t like there is the economics. I don’t blame the mountains, you see. But if there are no tourists, no Westerners that come to climb mountains for the trekking, for expeditions, we are dead.”

HOME FOR TSERING NOW is a white stucco apartment building in Ditmas Park, a Brooklyn neighborhood of shingled houses, wraparound porches, and manicured lawns. Shortly after we first met, he invited me to his place for lunch. Over spicy chicken and home-cooked dal, Tsering and Nima—luminously pregnant at the time—showed me the artifacts of their former life. There were photos of Tsering and other descendants of Tenzing Norgay taken in 1997, posing with Hillary. Beside a window hung a large photo of Tenzing himself, shrouded with a ceremonial silk kata. Locked away in the next room was one of his most precious keepsakes: a Tissot watch that Tenzing gave Tsering’s mother before his death in 1986, engraved by European fans. The inscription reads GLI HIMALAYANI ITALIANI—A TENSING—TRENTO 28-2-1958. (“The Himalayan Italians— to Tenzing—Trento, February 28, 1958.”)

Tsering and Nima left more than memories behind. They met in 1987 as students at the University of Darjeeling, married six years later, and in May 1997 had a daughter, Norkhila. Now ten, Norkhila lives back home with Tsering’s mother; she was eight months old when Tsering and Nima departed for the U.S. They had planned to fetch her shortly, but the family’s green-card process has been mired in limbo since 2001. Because of that, Tsering has been unable to go back, though Nima returned in 2003. But now that the paperwork seems to be on track, they hope to bring Norkhila to Brooklyn next year.

On May 23, 2003, Nima gave birth to the couple’s second child, a beautiful boy with blackbird eyes. Born a few days before the 50th anniversary of Tenzing’s Everest summit, Norsang Norbu Sherpa is among the first Sherpas to be American by birth.

He joins a vibrant, close-knit community. If the center of worldwide Sherpa culture is the Solu Khumbu, in America it’s Jackson Heights, the polyglot epicenter of Queens. At the corner of 37th Road and 74th Street, groups of women walk by in traditional Bhutanese robes, shopping bags from Bed Bath & Beyond in hand. Himalaya Video, at the corner of Broadway and 72nd, is the place to pick up a commemorative Everest T-shirt or the latest album by rapper Nurbu Sherpa, who recently moved to New York as well. “Representin’ K.T.M.C.” (short for Kathmandu City) is his big seller. Or how about a bootleg of Nhyu Bajracharya’s single “Ma Sherpa Ko Chhoro,” remixed with the sounds of an avalanche and grunting yaks?

Don’t be surprised by the Sherpas’ appetite for dance music. When it comes to partying, no one—not the sozzled freshmen of NYU or the coiffed scenesters of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg district—can hold a candle. New York’s Sherpas gather every weekend, almost without exception, in cavernous Queens banquet halls like Tangra, the Dhoka Club, or Five-Star Banquet. (Any large space will do.) Depending on the event, anywhere from 200 to 1,000 or more Sherpas show up; double that if the broader Himalayan community is involved. These throwdowns typically last until about 2 or 3 a.m., with plenty of dancing, Total Request Live style, and more than enough Heineken and Johnnie Walker Red to go around.

Last December, the Sherpas staged a benefit at the St. Vartan Cathedral, on 2nd Avenue and 34th Street, to raise money for a possible future visit by the Dalai Lama. Tsering and his friend Galgen Sherpa made sure I knew about it. “Every Sherpa’s gonna be there,” Galgen said.

“We are having coordination with Richard Gere-ee,” another explained. The Buddhist actor has allied himself closely with the Tibetan cause.

Richard Gere didn’t show, but an all-star lineup of Kathmandu musicians did—including Mingma, the rising hope of Sherpa pop here and in Asia; Nepalese crooner Nima Rumba; ponytailed Tibetan rocker Tsering Gyurmey; and petite Indian chanteuse Sindhu Malla. Headlining was Raju Lama, the Himalayan Bon Jovi, his sound equal parts grunge and power ballad.

Almost every Sherpa I’d ever met was on hand. Sonam Sherpa, a Transit Authority employee with the made-for-TV baritone of Tom Brokaw, appeared on stage in his usual getup of black T-shirt and sports coat, the night’s emcee. Mongolian Hearts, Raju Lama’s band, pumped out pulsing Bolly-pop as giant digital projection screens and skittering colored beams bathed the room in a cerulean glow. About two hours into the concert, Galgen led me backstage, waving us past a hulking bouncer and a throng of teenage Himalayan groupies clutching cameras.

In a small, smoky room, takeout containers were strewn across a table next to whiskey bottles and ashtrays overflowing with stubbed-out Marlboro Lights. Tsering Gyurmey, the Tibetan, smiled placidly before taking the stage with what appeared to be an electrified gourd. Sonam and Galgen were visibly starstruck but managed to look cool as a group of young women streamed in.

“These guys are huge,” said Sonam, slouching against the wall with his hands in his pockets. And he was right. “When we perform in Kathmandu,” Raju told me, “we get about 30,000 fans.”

Onstage, Raju high-fived people in the front row, pulling back with a finger wag if anyone tried to hold on too long. Mingma, making his U.S. debut, alternated between classical throat singing and rave-ups recalling House of Pain’s “Jump Around.” Too soon, Sonam belted out his last “THANK YOU NEW YORK CITY!” and the DJ fired up the sound system to keep the party going. As usual, video clips appeared on YouTube within hours.

SINCE WE MET, TSERING and I have rendezvoused often. “Que pasa?” he likes to say when I jump into the front seat.

Late on a cold night last January, we were parked on a sliver of sidewalk on the Lower East Side, near the corner of East First and Avenue A, outside Punjabi Grocery, another cabbie hangout, and across from Katz’s Deli, the scene of Meg Ryan’s famous fake orgasm in When Harry Met Sally. We’d just come from Williamsburg, where Tsering had gone to considerable effort to track down the hipster owner of a forgotten cell phone.

“Thanks,” the guy shrugged, grudgingly handing over a tip that Tsering had politely requested before driving all the way from Manhattan, his meter darkened.

Tsering brushed it off, but he says he’s routinely haggled with, harangued, stiffed, and abused by surly passengers. During a typical ten-hour, 150-mile shift, he might endure road-raging drivers, vomiting passengers, or the sights and sounds and aftermath of cab sex. “We all have our sorrows,” he once confided, “but as a taxi driver, there are so many times that people give you shit. They say, ‘This guy’s a taxi driver. They’re all the same.’ “

Even other minorities hassle him. “Look, I know. I cannot be a racist,” he said, “because I myself am a different race.” But he seethes whenever he hears about a member of any minority group blowing it—getting involved in prostitution or drugs or just slacking off. He feels like they’re wasting chances an honest, hardworking Sherpa would never miss.

Coming to America wasn’t Tsering’s first choice. All his life, he wanted to be a climber, like Tenzing Norgay. Technically, Tsering is Tenzing’s grandnephew—his mother, Ang Phuri, is Tenzing’s niece—but Sherpas make little distinction among members of the same clan, so Tsering was always considered a grandson. He and his younger sister, Lakpa Doma Sherpa, were raised in Ghang-la, the family house Tenzing was able to establish in Darjeeling after his famous climb. But early life for Tsering wasn’t peaceful: His father, Gombu—a Gurkha-regiment soldier and an accomplished boxer and drinker—beat the boy and his mother, and the couple divorced. Gombu moved across town, shunned by the family.

Tsering remembered a steady stream of visitors, journalists, and film stars presenting themselves at Ghang-la to meet Tenzing, who endured the attention good-naturedly—for the most part. “Sometimes he was in very shabby clothes with a sickle in his hand,” Tsering said, “and the Indian tourists used to come and say, ‘Hey, gardener, your boss is here?’ And he used to act very innocent and say, ‘Oh, he’s gone to the office’ or ‘He’s gone to Switzerland.’ And they’d go away.”

Amid the tumult, Tsering became, in his own words, “a very naughty child.” He told me a story that I found hard to believe until his sister, Lakpa, confirmed it: When Tsering was around 12, Tenzing caught him trying to sneak into the house through a window when he’d forgotten his keys. The next morning he hauled the boy to the stairwell, hung him upside down from a climbing rope, lashed him with a cane, and ordered the family servant not to untie him until the end of the day. The servant cut him down a short time later, the hard lesson learned.

“He was a very strict man, a man with principles,” Tsering said. “And I respected him. But I could not look him in the eyes. When he looked at me, he saw my father, and he did not like him at all.”

Mountaineering was all around Tsering at Ghang-la. Eight family members have summited Everest, from Nawang Gombu Sherpa, Tenzing’s nephew, who accompanied Jim Whittaker on the first American ascent in 1963, to Tenzing’s son Jamling Tenzing Norgay, whose memoir Touching My Father’s Soul chronicled his own 1996 summit, and grandson Tashi Tenzing, who reached the top the next year. Every Sherpa knows their names.

“I wanted to climb Everest,” Tsering told me several times. And for a while it looked like he would. In between schoolwork, he was a guest instructor at the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, which Tenzing had established. He climbed to 18,000 feet during training excursions and worked several seasons at HMI’s Kanchenjunga base camp.

But then, in 1989, on a trek near the India-Nepal border, Tsering woke up from a nightmare in which he’d seen dead friends and family. His heart palpitating at around 120 beats per minute, he staggered outside his hut, gasping for breath. When it happened again a few months later, while he was courting Nima, he knew something was seriously wrong. Several years passed before an echocardiogram showed that he had a right bundle branch block, a congenital and potentially fatal disorder that thwarts the flow of blood to the right front ventricle. Tsering’s Everest dreams evaporated. He’d never felt like a true part of Tenzing’s clan, and now he was even further outside it.

But thanks to the opportunities he’d received from being part of that family, guiding wasn’t Tsering’s only option. With a degree in political science and economics from the University of Darjeeling, he rethought his future, even as he continued to lead treks at lower elevations. Lakpa was already living in Richmond, married to an American, and, with financial help from family members, Tsering and Nima joined her, settling a few months later in New York. Leaving Norkhila with Ang Phuri was meant to be a temporary measure.

“My life is already burning now,” Tsering said to me once, sounding more wistful than bitter. “I am like a candle. But the light which the candle gives is going to be good for the coming generations, which I can see in America.”

TEN YEARS INTO his American life, Tsering Norbu Sherpa is thriving. He hasn’t yet put his degree to use—he’d need two more years of classes to achieve U.S. standards, he says, a hurdle that other educated Sherpas also face. But driving a taxi has given him and his family a steady means of support. He and Nima and their friends save up by working hard, eating at home, and hanging out together on weekends, dropping a few bucks on gin rummy and swapping ring tones like “Chyangba Hoy Chyangba,” a ridiculously catchy Nepalese jingle. Galgen just bought a good-size new apartment in Queens with his taxi wages.

Despite the profits, life in the city takes a toll. Lhakpa Gelu Sherpa, one of the Utah SuperSherpas, lived in Queens for 14 months before decamping to Salt Lake. “Wow, very big city,” he said, laughing at the memory of his stint in New York. “All those people underground! Very hurry, hurry, hurry!”

“You’re not able to give much time to your family,” Tashi Gyalzen Sherpa told me, wearily answering two phones at once in his travel-agency office in the back room of Himalaya Video. “In Nepal, you worked for three months and relaxed the other nine. Over here, most of your money goes to rent. Back home, people think, ‘You must be making ‘dollar-crazy!’ but I tell them, ‘No, you have to work hard.’ It’s difficult.”

The downside of separation crashed into Tashi’s life in May, when his sister, Pemba Doma Sherpa—the first Nepali woman to summit Everest via the North Face—was killed while descending 27,940-foot Lhotse. Unable to travel on such short notice, Tashi had to watch footage of her somber cremation at Everest’s Tengboche Monastery on SherpaKyidug.org, the New York Sherpas’ virtual home.

Moments like this bring up the not-so-small issue of reconciling American and Himalayan values. “We get homesick,” Nima says. And she worries about the transition Norkhila will face when they can finally bring her here. “I will try to teach her the culture, but it will be hard,” she acknowledged. “Once we have all the papers, we will take the whole family back to Darjeeling every year. We will show her.”

One might think that leaving the traditional homeland would be frowned upon, but generally that’s not true. “There’s no shame in it,” Lakpa told me during a stopover in New York last spring. After ten years in Virginia, she was taking her three-year-old son and moving to New Delhi for a consulting job. “As long as you preserve our traditional ways, others are happy for you,” she said.

“My main goal is education for my three kids,” Apa Sherpa, in Utah, says. “That way, they can help in Nepal in the future. We’re very happy in Salt Lake. The kids are doing good. Everybody achieves. You don’t see that in Kathmandu.”

Tsering and the other Sherpas know that the money they send only partially compensates for the pain of empty rooms and divided families. But the danger, instability, and diminishing returns of guiding have pushed them to reach for another plateau, a place in the world beyond thin air.

“I am trying to break up my cycle,” Tsering told me. “My grandfather was a mountaineer. My parents were mountaineers. I grew up as a mountaineer. I don’t want my kids to grow up as mountaineers. Sherpas are meant to be doctors, to be engineers, computer programmers! And why not? In the future, you might see a Sherpa baseball player! Or, in American football! OK, maybe not in basketball—I hate basketball. Sherpas are short people, you know.”

ONE SUNDAY LAST SPRING, New York’s Sherpas gathered at Five-Star Banquet, in Long Island City, to celebrate the Buddha’s birthday. As shiny-pated monks in saffron robes strolled around, working up the energy to start chanting, a black Mercedes SUV pulled up, hatchback raised. Gingerly, the Sherpas hoisted out a large, gold-painted Buddha shrouded in silken fabrics and a halo of bright, blinking LEDs. They carried the idol, procession style, back along a chain-link fence toward the hall.

Suddenly the monks made a glorious din with a panoply of instruments. Traditional brass bugles blurted out a rubbery basso salute: byuuur. Trumpetlike gelings buzzed a high note: eeeerepree. Then came the damaru, two-sided rattles, which went pockitypockitypockity. Above the din, crystalline dilbu, tiny brass bells, tzeeeng’d brightly. Despite the racket, at least one Sherpa found it a good time to make a cell-phone call.

But the most important thing on display wasn’t the golden Buddha; it was the set of blueprints hanging by the entrance. Over the past month, the Sherpas had been raising funds to construct their own cultural center in Queens. The plans called for a large meeting hall, prayer space, cooking areas, and ample storage; the facade would be decorated in the bright primary colors of the Potala Palace, in Lhasa, Tibet. Hanging below the plans, a list of names showed which Sherpas had donated so far, with about 60 already committed. Each amount ended with a 1 (as in $101).

“We see the zero as no progression,” explained Galgen.

The monks plopped onstage cross-legged and cracked Heinekens, the heavy lifting finished. As Galgen worked the microphone like a preacher, Sherpas approached with checks in hand, receiving a blessing and a kata from the monks. After two hours Galgen abruptly finished, sweating, a look of astonishment on his face. In his hands were checks for amounts up to $15,001. With only 80 Sherpas accounted for, the monthlong drive had raised more than $426,000 in pledges. The goal of $1 million suddenly seemed within reach. (Today pledges have reached $625,000, a third of that in ready cash.)

A few months earlier, as the city’s temperatures rose in bizarre lockstep with the holiday shopping frenzy, I had joined Tsering, Nima, and their little boy, Norsang, along with Galgen and his girlfriend, Phinjo Tshering, for a trip into the city. On a weirdly subtropical day, we parked Tsering’s cab near Union Square and took the subway up toward Rockefeller Center, where the tree-gaping crowds were beyond estimation. (“Follow the fat ladies!” Tsering cried. “It’s the only way!”) The soaring tree mesmerized Norsang, but when a Santa Claus character appeared, he paid him exactly zero attention. “He doesn’t know him,” Nima said with a shrug.

We continued over to Herald Square, where another galling mass of New Yorkers was on hand. At a Buddhist stupa, pilgrims circle three times to earn the proper blessing, and at Macy’s this time of year, tourists seem to do the same. As we rounded a corner, Tsering lifted Norsang, wearing a tiny blue Yankees jacket, onto his shoulders. Norsang leaned over to whisper in his father’s ear. In a window we’d just passed, there was an animatronic white lion roaring in a fake snowy field; he wanted to see it again. As they turned back, Norsang let out a squeal. Then they vanished completely, invisible in the multitudes.