CHANGEEVEN MONUMENTAL change doesn’t have to come from the top. As new titles by two of sustainability’s most visionary champions make clear, ordinary citizens acting in their own communities can jump-start a revolution.

Want it? Get it

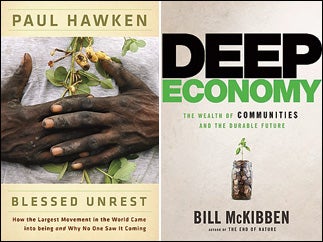

Buy and at Amazon.com.

Since 1983, eco-entrepreneur Paul Hawken has written six books, including 1999’s paradigm-shifting Natural Capitalism, with Amory Lovins and L. Hunter Lovins (see “Canon Fodder” ). In Blessed Unrest: How the Largest Movement in the World Came into Being and Why No One Saw It Coming (Viking, $25), Hawken surveys the globe and describes a powerful, under-the-radar trend: The environmental, social-justice, and indigenous-culture camps are converging to form a massive humanitarian movement. By “unrest,” Hawken means everything from workers demanding better pay to tribal groups resisting mining on their lands. But while these movements start, and often stay, at a grassroots level, their collective presence can resonate globallyas when a protest at the opening of a McDonald’s in Rome, in 1987, blossomed into the international Slow Food campaign. “The movement doesn’t agree on everything, nor will it ever,” Hawken writes. “But it shares a basic set of fundamental understandings about the earth, how it functions, and the necessity of fairness and equity.” Twenty-first-century activists don’t want to put the Man up against the wall. They just want him to produce shade-grown organic coffee.

Bill McKibben, it’s safe to say, is all for blessed unrest. Over the past 20 years, the ���ϳԹ��� contributor has proclaimed the end of nature, urged us to switch off our TVs, and survived for a winter eating only food produced in Vermont’s Champlain Valley, where he lives. In Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future (Times Books, $25), he challenges the cult of economic growth. We used to believe that more is better. Expanding GDP? Good. More stuff? Great. Now, he argues, “you have to choose between them. It’s More or Better.” McKibben acknowledges that growth sustained the American dream following World War II. But, citing study after study, he sets out to prove that rising income does not correlate to personal satisfaction. “We’re richer,” he writes, “but we’re not happier.” Deep Economy plots a new path, one seemingly inspired by longtime local champions like writer Wendell Berry, that essentially boils down to two actions: Stop buying cheap crapborrow and lend well-made stuff with your neighborsand shop locally. “If we grew most of our food close to home, we’d use far less energy in the process, helping alleviate both oil shortages and climate change,” he writes. What makes the book compelling isn’t McKibben’s call for eco-righteousness; we all know we could do better by the planet. It’s his convincing argument that engaging with a local “deep economy” can bring every one of us selfish bastards a happier, richer life.