Before sunrise, one Monday morning in February last year, Kate Matrosova’s husband dropped her off at a trailhead in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. An experienced and well-equipped outdoorswoman, Matrosova planned to complete the Presidential Traverse that day, a hike that would see her eventually summit Mount Washington, after completing several lesser peaks leading to it. She would .

Last week, I hiked up the mountain with Steve Dupuis, a and search and rescue volunteer. He was one of the first to respond when Matrosova’s personal locator beacon went off. He and his team would eventually brave wind gusts of 140 mph, and wind chill as low as -100 degrees trying to reach her. During the rescue attempt, the measured temperature of -35 degrees on the mountain’s summit made it the second coldest place on earth, after the South Pole.

“God only knows why she didn’t turn back,” Dupuis lamented to us. A malfunctioning beacon indicated Maltrosova might have been in three different locations, and the team wasted valuable time by splitting up to search each. By the time they found her at the third, she’d died of exposure.Â

The day we hiked, the temperature at Mount Washington’s summit reached 56 degrees. No minus. The sky was blue, and there was no discernible wind. Nevertheless, before we set off, a state policeman gave us the description of a missing hiker. Forty-seven-year-old Francois Carrier of Quebec was last seen embarking on the hike wearing flip flops and a T-shirt. Several hours later, on the way down, we came across search and rescue workers walking a police line through the woods, looking for him. Yesterday, . His car still sits in the parking lot at the Pinkham Notch trailhead. Temperatures on the mountain reached -20 degrees on Monday morning.Â

If Carrier is pronounced dead, he’ll take the mountain’s total above 150 kills, since records began in 1849.Â

Why does such a small mountain kill so many people? One reason is obviously the extreme weather. “Mount Washington sits at the intersection of several major stormtracks,” explains Weather Observer Tom Padham. He's stationed at the mountain’s summit, and gave us a tour of his weather station. The jet stream carries nearly every storm moving west-to-east, and southwest-to-northeast across the country, right over Mount Washington. There, they intersect with weather systems moving south-to-north, up the Atlantic coast. Just a few days after our visit, Padham recorded the following video:

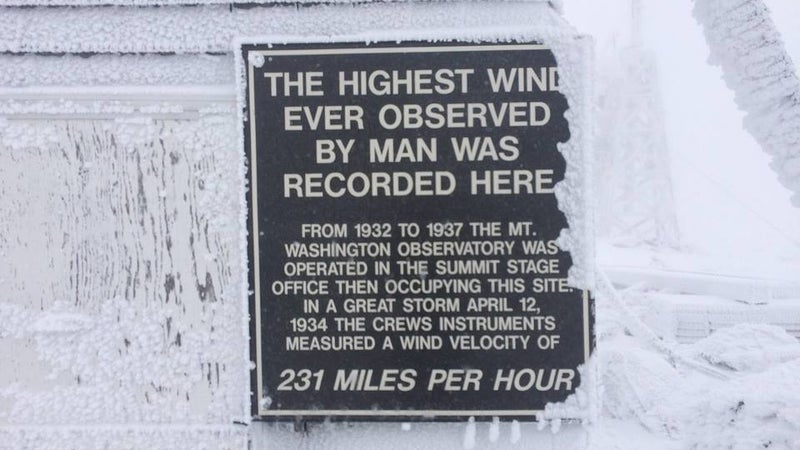

The mountain also sits at the throat of a natural funnel. Land to the west of the mountains is mostly flat, creating few obstructions. As it blows in out of the northwest, that wind encounters lower mountains fanning out from Washington, channeling air directly to it. The mountain’s own topography also plays a role; its very steep western face compresses the wind caught in that funnel even further. “Air functions as a liquid,” explains Padham, “and as you compress a liquid, it must accelerate.” The highest wind speed ever directly observed by humans was on the summit. There, in 1934, two weather observers stood outside with an anemometer and measured wind speeds of 231 mph. The device stopped working at that speed, even as they felt it gust stronger.

Due to that extreme weather, trees stop growing in the White Mountains at about 4,400 feet. On Mount Washington’s eastern face, that leaves about a mile and a half of hiking, totally exposed, often in whiteout conditions, before you reach the summit. Regular cairns along the route attempt to steer hikers away from the thousand-foot precipice just a few dozen feet to the south.Â

Before that particular trail—Lion’s Head—reaches the treeline, it first climbs through several steep gorges, requiring hikers to scramble up boulders. If snow and ice are present, it can, and does fall as people pass through. A prominent sign at the trailhead warns of this danger, but it still manages to catch people unaware.Â

An from 1997 reads: “On January 5, the body of Alexandre Cassan—one of four members in a party attempting an ill-advised winter ascent of the 6,288-foot peak—was discovered by a U.S. Forest Service snow ranger about one hour after the 1420 avalanche near the Lion Head Trail on Mount Washington’s steep southeast slope. All but one hand of Cassan was buried in the snow.”

During the summer, when risk of avalanches and icefalls abates, danger to hikers persist. The trails themselves—including the popular Tuckerman Ravine Trail—are strewn with loose, basketball-size rocks. Practically the entire trail is one big tripping hazard, just waiting to twist an ankle, and, if that happens, you won’t be able to walk off the trail under your own power. The terrain only gets more fraught as you turn onto Lion’s Head and attempt to climb the peak’s steep southern approach. And that’s the easiest trail you can find to the summit.Â

Of course, hiking isn’t the only activity that takes place here. Tuckerman’s Ravine, just to the south of the peak, is a popular backcountry skiing bowl. Even in the middle of May, we could see people climbing up its 40-degree, crevasse-filled and rock-strewn face, just to get one last run of the season in.Â

Dupuis, our guide, was on hand for another ill-fated rescue attempt there in 2012. A man fell into a crevasse, the weather turned, rescuers were unable to reach him that night, and he froze to death as temperatures fell. It was days before they were able to recover his body. Not everyone enjoys the balmy weather we had last week.Â

I asked Padham, the weather observer, how often the mountain sees blue skies. “Maybe 10 days a year,” he responded.Â

Even on this clear, calm day, with the forecast calling for it to remain the same overnight, Dupuis insisted we carry rain shells, base layers, down jackets, insulated gloves, a warm hat, and bring extra food and water. To avoid the ankle twisters, he also insisted on over-the-ankle boots. And, even in mid-May, much of the 4.2-mile hike remains covered in ice and snow. Microspikes were another essential he insisted we carry. I didn’t use mine, but there were probably a couple of places I should have.Â

Dupuis takes the risks the mountain offers seriously. Hiking much faster than the rest of the group, I found myself in need of a bathroom break. The kind that involves a trowel and baby wipes. When I suggested to Dupuis that he carry on with the group, and that I’d catch up in no time, he insisted they all wait while I walked out of site for a few minutes. Many jokes were had at my expense after.Â

His safety-first approach is in contrast to that of most other people we observed that day. A father and daughter hiked up after us, and arrived on the summit as we were enjoying a lunch of dehydrated backpacking food from . “Where can we buy lunch?” The father asked a weather observer. He hadn’t brought any water either, and spent several minutes drinking from a tap at the weather station. He and his daughter were wearing jeans and t-shirts, he had a Harvard sweater tied around his waist.Â

As we were departing, the father asked Dupuis if there were any faster routes down the mountain. His dismissive response? “Not in those shoes.” They were wearing slick-soled tennis shoes and I passed them a few minutes later scooting down a particularly slippery portion of the trail on their butts. Dupuis has had to put his own life at risk too many times rescuing the unprepared to be nice to them.Â

And that’s the real reason Mount Washington kills. Close enough to the northeast urban conurbation that a summit can be had in a day trip from Boston, or an overnight from New York, the mountain offers some of the best, and most easily-accessible hiking and skiing in the region. 250,000 people are said to visit each year. Doing that is as easy as pulling into the parking lot, and hitting the trailhead. There’s warning signs, there’s stories, and there’s even guides you can hire, but most people are content just to head out for a walk, and see what happens; ignorant of the weather, the terrain, and the dangers. It’s tempting to say that the government should step in, and require permits, or better patrol the trails, but it’s also easy to conclude that if someone is going to set out on a mountain notorious for its death-rate and extreme weather in flip flops, that they’d find a way to die elsewhere if this hike wasn’t available.Â

Even the experienced are prone to underestimating the mountain’s risks. Dupuis says Matrosova’s gear was good, “But she didn’t have any cushion.” As the weather turned, which here it’s prone to do, she didn’t have a shelter, she didn’t have extra insulation, she didn’t have a hiking buddy. With any of those things, much less all three, Dupuis says they probably could have reached her in time. On Washington, it’s lack of preparation, not the mountain, that kills.Â