OUR ALREADY BAD DAY took a terrible turn when Kevin fell into the crevasse. Lucky for him, he was tethered to a blind man. Steve felt the sharp tug and immediately dropped to his butt and dug his crampons into the ice. This gave Kevin enough time to kick his toe into the opposite wall of the crevasse and stop, armpits-deep, his free leg dangling over the darkness. I had fallen in beside him but used my trekking pole to span the gap and went in only up to my thighs. The fourth member of our party, Matt, was unroped and 20 yards away. I backed out and scooted across the snow on my belly, and together Steve and I pulled Kevin, gently, from the fissure.

But we were still lost in a blizzard and trapped in a crevasse field on the slopes of 18,510-foot Mount Elbrus, the highest mountain in Europe. A thunderstorm was parked overhead, and lightning flashed around us. I might die out here, I thought. I’m going to be on the news. Four climbers lost and presumed dead on Elbrus. I’m actually going to be that guy.

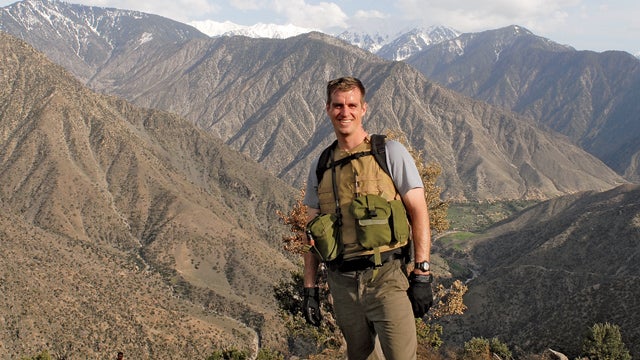

I had felt that sort of extended dread just once before, in southern Afghanistan in 2010, in a farmer’s compound surrounded by, and under fire from, the Taliban. But back then other people had known we needed help. Reinforcements were en route to hammer the enemy with machine-gun and rocket fire. Out in the crevasse field, no one knew we were in trouble. This was bad. But confrontations with mortality can have merit; they certainly spur reflection on the risks you take and whether they’re worthwhile.

I had just turned 38, nearing the end of a decade that began with war and led me, unexpectedly, to the outdoors. I spent my 30th birthday on a highway in southern Iraq, driving a humvee north from Kuwait for a 12-month deployment as an infantryman in western Baghdad. The risk was so extreme, so over the top compared with everything else I had known in my life, that there was little I could do but rely on my training, try to keep myself and my friends safe, and hope for the best. The more I was around danger, the less dangerous it seemed. Random gunshots or an explosion two streets away weren’t much to worry about. And it was exciting.

After leaving the Army at 32, I made several reporting trips to Iraq and Afghanistan, because there were important stories to be told. But also, if I’m being honest with myself, I returned to war zones because of the thrill of the unknown, when the day could turn upside down at any moment. On foot patrols through the mountains along the Pakistan border, or through bomb-infested farmland in southern Afghanistan, the air hummed with tension. I’m not reckless, but I came to crave unpredictable moments, even though it sometimes felt like risk for the sake of risk, which I knew had the potential to kill me. Being in war zones fostered a strange, fatalistic rationalization: things would work out OK because they had thus far, and if things didn’t work out, that was somehow OK, too, because the event would likely be so catastrophically bad that I wouldn’t be alive to worry about the outcome.

Writing about the military and veterans led me to Nepal in 2010, where I climbed 20,075-foot Lobuche with 11 wounded Iraq and Afghanistan vets. There I found the camaraderie of shared experience and what seemed like a safer version of the excitement I had known in the military. The next summer, I climbed Kilimanjaro with one of those veterans, Steve Baskis, who was blinded by a bomb in Baghdad. A year later, Steve and I planned a trip to Elbrus with several other friends, including Kevin Noe and Matt Murray. By then, outdoor adventure had become a core part of my life, serving as a transition from the heady recklessness of war.

Being in the mountains offered another reminder that the world is raw and unpredictable, even if the danger often seemed more like perception than reality. Before the trip to Russia, I read that Mount Elbrus is a straightforward climb, one of the easy Seven Summits—like Kilimanjaro with more snow on top. We had been told that the route was well marked with small flags, so a guide wasn’t necessary.

Then the day turned upside down. Hours before entering the crevasse field at 10 a.m., we turned back shy of the summit when Matt became sick and couldn’t continue. It was still dark, but the arrival of daylight brought no clarity. A pounding wind pelted us with ice and snow and cut visibility to 20 feet. The storm cleared briefly as we worked down the mountain to the edge of what seemed to be a snowfield. We couldn’t see all the fissures, covered as they were by a fresh layer of ice and snow. Because Steve is blind, he was roped to Kevin, but Matt and I were unroped as we traversed what seemed like the easy grade of the lower mountain. It took Kevin’s fall for us to realize that we’d veered into a crevasse field that now stretched between us and base camp.

Bad decisions led us here, but we made some good decisions, too. We had turned back from the summit push as a group, and after roping up we listed our options and took what we determined by consensus to be the best course. We worked together and slowly made our way through the crevasse field, with Kevin as point man, stabbing a pole through thin ice searching for snow bridges. Sixteen hours after setting off for the summit, we shuffled back into base camp.

Later, I pondered the choices that led to those hours in the crevasse field and what could have been. I realize now that this had not been just another dicey moment, the same as a near miss in Iraq or Afghanistan. Elbrus represented a passing over from the at times uncontrollable danger and uncertainty of my early thirties, when, despite extraordinary preparation, so much had to be left to chance.

I still don’t like knowing exactly how my days will play out. I will always crave risk and unpredictable elements in my life, things the outdoor world certainly offers. But unlike a war zone, I can mitigate most of the danger by making good decisions. It’s rare when there is nothing I can do. The responsibility is on me.������������������������������ ��

Contributing editor Brian Mockenhaupt wrote about sports psychologist Michael Gervais in January.