A Short Walk in the Wakhan Corridor

For decades, no one had traversed the entire length of the Wakhan, following the old Silk Road from the northward bend of the Panj River. We had no idea if it could be done.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The old Wakhi horseman sucks deeply on his pipe, the opium glowing scarlet in the darkness, and blows smoke in my face. We're lying side by side on pounded wool mats in a cavelike hut in far northeastern Afghanistan. The stone walls and stick ceiling drip with black tar from decades of burning yak dung. A goat is butting its horns against the crooked door. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, the sheep are shu┬Ąling nervously inside the stone corral, waiting for a wolf to take one of them.

The fire is almost out and everyone is asleepÔÇöpressed together for warmth like the animalsÔÇöexcept the horseman and me. His wind-shot eyes are shut. He inhales, his craggy face relaxing, then exhales, the psychoactive smoke swirling around my head.

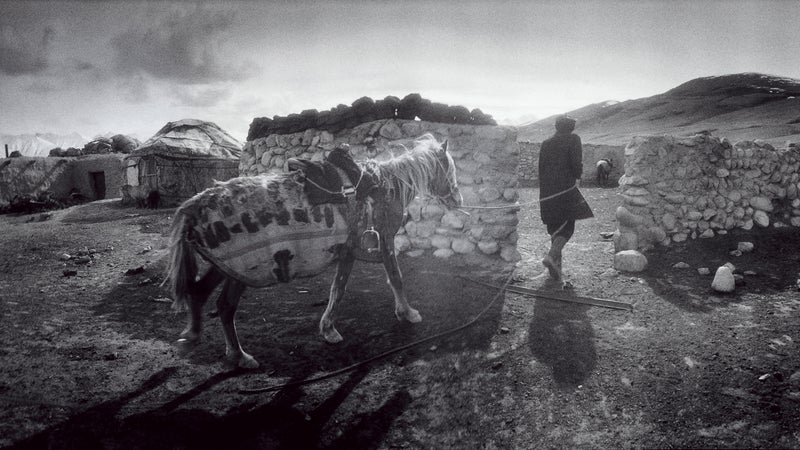

Another long day done. Our team of eightÔÇöthree Americans, our Pakistani guide, and four Wakhi horsemenÔÇöis walking the Wakhan Corridor, Afghanistan's ancient, forgotten passageway to China. We are more than halfway through, en route to Tajikistan. Marco Polo passed this way 734 years ago. It was medieval then, and it still is.

The Hardest They Come

Former Editor Hal Espen on finding the embodiment of the unlikable idea of literate badass adventure.

Former Editor Hal Espen on finding the embodiment of the unlikable idea of literate badass adventure.It was late afternoon today when we climbed out of the dark canyons up onto the treeless, 13,000-foot steppe. Two vultures, with their pterodactyl-like six-foot wingspans, were circling above a yak carcass. Our day's destination, a place called Langar, turned out to be this solitary hut out on the vast brown plain. A gaunt woman in a maroon shawl invited us into the smoke-choked shelter and gave us salt tea in a chipped china cup. Her name was Khan Bibi. She was 35, but she was weather-beaten and missing teeth and looked twice her age. She began making flatbread, wetting handfuls of flour with water from a pail. She sent her youngest child, a four-year-old girl whose nose was running with green snot, out to collect disks of fuel. With blackened hands the woman slapped the slabs of dough against the horseshoe curve of the clay hearth. As they finished baking and fell off into the fire, she reached into the flames and passed them to us.

We all went back outside when we heard a chorus of baaing. Khan Bibi's husband, Mohammad Kosum, 45, and their seven-year-old son, both in black Russian fur caps with earflaps, were bringing the sheep and goats into the corral. Together this family of four began lifting lambs and kids from a cellar, placing them with their correct mothers, allowing them to suckle, then dropping them back down into the two-foot-deep hole where their combined body warmth would keep them alive. With 800 animals to move, the process lasted till dark.

Khan Bibi returned to the hearth and squatted there for the next three hours, making us rice and more flatbread and more salt tea. There was no electricity, no lamp, no candle. Dim orange firelight and a shaft of blue moonlight cut down through the whirling smoke from a square hole in the roof. The tiny girl fetched water from a snowmelt creek that runs through the reeking carcasses of yaks that died during the snowy spring. When we were all fed, Khan Bibi curled up on the shelf above the fire with her two children and pulled a yak-hair blanket over the three of them.

Now, hours later, the old horseman is next to me, blowing smoke in my face. He's on his fourth or fifth bowl. I can't keep track anymore. I'm floating on secondhand smoke, back to my first day in Afghanistan.

I'm running up Aliabad, a mountain in the middle of Kabul. Tilting dirt streets with runnels carved down the middle by sewage. I pass two faceless women, heads trapped inside helmets of blue mesh. In the rocks above the flat roofs, I pass a shepherd girl shooing sheep along the mountainside. I reach the top and begin to run along the ridgetop in pink light. Up and down through trenches, stepping on piles of rusty four-inch-long bullet casings, skirting a blown-apart artillery gun, leaping an ordnance dump.

Below me, Kabul is brown. Everything in Afghanistan is brown. Smog obscures the city, but there's not much to see anyway: mud-brick houses and miles of ruins. Supposedly in the seventies there were paved, tree-lined streets and outdoor caf├ęs and a university and women with faces who wore flowered skirts. Today it is apocalypticÔÇöthe destroyed capital of a country that has been at war, with invaders and itself, for 25 years. Make that 25 centuries.

I'm running along thinking about baby-faced, flak-jacketed American soldiers in their armored convoys when I glance at the ground and stop dead in my tracks.

I'm surrounded by rocks painted blood-red. I know what this meansÔÇöit's the first thing you learn upon arriving in Afghanistan: land mines. My eyes shoot side to side, searching for the rocks painted half red, half white. Cleared paths through minefields are lined with such bicolored rocks, the white side indicating safety.

But there is no path. I hold myself motionless. Try to breathe calmly, look over your shoulder. I am 20 feet into the minefield. Very carefully, step backwards. I place one foot precisely in its own footprint. Do this with the other foot. Delicately, imagining myself as weightless as the ghost I could become, I retrace my steps.

For decades, no one had traversed the entire length of the Wakhan, following the old Silk Road from the northward bend of the Panj River to the far end in Tajikistan. We had no idea if it could be done.

Beside me, the horseman is still smoking. A few days ago, on the road outside Kabul, I met a man whose 11-year-old son, Gulmarjan, was killed by a land mine while tending a flock of goats. Now, in a hazy, smoky dream, I see Gulmarjan running through red rocks, chasing a goat. Suddenly he's up in the air, his face stricken, blood splattering the brown sky and the brown earth and his feet still in his boots but not attached to his knees. My friend Greg's voice floats back to me, saying, “Three million land mines in a country of 25 millionÔÇöthat's at least one for each family… . The Russians made ones that looked like little butterflies. Curious children still pick them up …”

The horseman is asleep, his face smashed against the wool mat, the pipe still glowing. Gathering up my sleeping bag, I escape the hut. The air is ice-sharp, the sky buckshot with stars, the walls of the encircling mountains black, the snow along their crests as luminescent as a crown. I walk out into the pale-blue steppe and find a spot among the slumbering yaks.

I slide into this distant night in no-man's-land. Lie back, look up, breathe. Safe and sound in this eternally unsafe, unsound country.

In 2000, Greg Mortenson and I hatched the idea of traversing the length of the Wakhan Corridor, the thin, vestigial arm of northeastern Afghanistan that extends eastward to the border of China, separating Tajikistan from Pakistan. As founder and director of the Bozeman, MontanaÔÇôbased (CAI), a nongovernmental organization that has built more than 50 schools in the tribal borderlands of Pakistan and Afghanistan, Greg had plenty of experience navigating the region's dicey political landscape.

We were planning to go in the fall of 2001. Then, on September 9, Ahmed Shah Massoud, commander of Afghanistan's anti-Taliban Northern Alliance, was assassinated by Al Qaeda suicide bombers. Two days later, 9/11. A month later, American cruise missiles were detonating on Taliban positions. Within half a year, the war in Afghanistan was putatively over, but it wasn't. It's never over in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is a palimpsest of conquest. The Persians ruled the region in the sixth century b.c., then came Alexander the Great 200 years later. The White Huns in the fourth century a.d., Islamic armies in the seventh, Genghis Khan and the Mongols in the 13th. It wasn't until the 18th century that a united Afghan empire emerged, then came the British, then, in 1979, the Russians. And now the Americans and their allies.

In October 2004, Afghanistan elected President Hamid Karzai, but his control barely extends beyond Kabul. As it has been for centuries, the Afghan countryside is ruled by tribal and regional leaders. It's a complex power network fraught with shifting allegiances. In the eighties, Afghan mujahedeen (“freedom fighters”) were armed and funded by the CIA to resist the Russians. After the Soviet occupation ended, in 1989, Afghanistan plunged into a state of internecine fighting: WarlordsÔÇöregional leaders backed by independent militiasÔÇöclashed, and the country fractured into a patchwork of fiefdoms. In 1996 the Taliban, a generation of Afghan Islamic fundamentalists that had grown frustrated with civil war, seized control of Kabul. They subsequently gave safe haven to Osama bin Laden and his Al Qaeda fighters. Today, despite the presence of 33,000 NATO and coalition troops, Afghanistan remains a violent, dangerous mess.

If any region of the country stands apart, it's the remote, sparsely populated Wakhan Corridor, which has been spared much of the recent bloodletting. Carved by the Wakhan and Panj rivers, the 200-mile-long valley, much of it above 10,000 feet, separates the Pamir mountains to the north from the Hindu Kush to the south. For centuries it has been a natural conduit between Central Asia and China, and one of the most forbidding sections of the Silk Road, the 4,000-mile trade route linking Europe to the Far East.

The borders of the Wakhan were set in an 1895 treaty between Russia and Britain, which had been wrestling over the control of Central Asia for nearly a century. In what was dubbed the “Great Game” (a term coined by British Army spy Arthur Conolly of the 6th Bengal Native Light Cavalry), both countries had sent intrepid spies into the region, not a few of whom had been caught and beheaded. (Conolly was killed in Bokhara in 1842.) Eventually Britain and Russia agreed to use the entire country as a buffer zone, with the Wakhan extension ensuring that the borders of the Russian empire would never touch the borders of the British Raj.

Only a handful of Westerners are known to have traveled through the Wakhan Corridor since Marco Polo did it, in 1271. There had been sporadic European expeditions throughout the second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. In 1949, when Mao Zedong completed the Communist takeover of China, the borders were permanently closed, sealing off the 2,000-year-old caravan route and turning the corridor into a cul-de-sac. When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, they occupied the Wakhan and plowed a tank track halfway into the corridor. Today, the Wakhan has reverted to what it's been for much of its history: a primitive pastoral hinterland, home to about 7,000 Wakhi and Kirghiz people, scattered throughout some 40 small villages and camps. Opium smugglers sometimes use the Wakhan, traveling at night.

In 2004, American writers John Mock and Kimberley O'Neil crossed much of the Wakhan, exiting south into Pakistan. As far as Greg and I could find out, for decades no one had traversed the entire length of the Wakhan, following the old Silk Road from its entrance at the big northward bend of the Panj River all the way across to Tajikistan. We had no idea if it could even be done.

By the time our schedules┬ámatched up, four years later, Greg was so busy running the CAI that he no longer had time to attempt the Wakhan traverse. But he was still passionate about the journey, and delighted to help make it happen. In his former life he'd been a climber and adventurerÔÇöit was the path that had led him to aid work. Coming off K2 in 1993, weak and exhausted, he'd been taken in by villagers in Pakistan. Because of their kindness, Greg had promised to return the following year and build a school. Which he did. Three years later, he founded the CAI.

Greg believed that the only way to truly understand Afghanistan, with all its contradiction and complexity, was total immersion. Excited about the trek, he found a partner for me: Doug Chabot, director of the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center, in Montana, and a longtime Exum mountaineering guide. In an e-mail, Greg described Doug as “a tough, hardworking, easygoing, non-ego guy.” Since we planned to attempt at least one virgin peak in the Wakhan, Chabot's avalanche experience “would be good life insurance.” Our plan was to cross the Wakhan from west to east, using a four-wheel-drive van as far as we could, then going by foot or horseback.

The first time we all assembled was in Greg's dingy room in the Kabul Peace Guest House, a small hotel in central Kabul, in late April 2005: Greg, 47, comfortably attired in a dirt-brown shalwar kameez; Doug, 41, tan, trim, with big green eyes and an inimitable laugh; and Teru Kuwayama, 35, a New YorkÔÇôbased photographer who had previously shot in Pakistan and Iraq. We'd be relying on Greg's contacts with regional leaders to secure safe passage through the Wakhan, but the real uncertainty was getting out of Afghanistan. Although we had visas for Tajikistan (and China, just in case), none of us knew anything about the borders at the end of the Wakhan. We could be stopped by Tajik guards and sent back, forced to retrace our journey in reverse. Or we could be arrested.

“It took the Russians only a few weeks to take AfghanistanÔÇöjust like you Americans,” and Afghan told me as we ate charcoal-grilled sheep in the streets of Kunduz. “And I believe the regret began immediately.”

The corner of the Wakhan where Tajikistan, China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan meet is sensitive territory. On the China side, the Uighur, a Muslim Turkic population of eight million, are clamoring for independence. In Kashmir, Pakistan and India have yet to resolve their decades-old dispute over borders and ethnic governance. To the north, the former Soviet republic of Tajikistan is run by an unstable, authoritarian government, and the country is an integral part of the global opium pipeline. (As much as half of all opium produced in Afghanistan is exported via Tajikistan.) Islamic fundamentalist guerrillas have been known to infiltrate the region; if we encountered themÔÇöor were mistaken for guerrillas ourselvesÔÇöit could get ugly.

Greg said he'd try to meet us within ten days in Sarhadd, in the middle of the Wakhan. He introduced us to 50-year-old Sarfraz Khan, his right-hand man.

“Sarfraz will be going with you,” he said.

A tall, dark, mustached man stood up and extended a crippled hand toward me. “I am very pleased to meet you,” he said. Over the years Greg had told me stories about Sarfraz. Born and based in the Chapurson Valley, in northern Pakistan, he had served as a commando in Pakistan's elite mountain force; while stationed in Kashmir, he was wounded twice by Indian troops. One bullet passed through his palm and paralyzed his right hand. He spoke English, Urdu, Farsi, Wakhi, Burushashki, and Pashto. He'd spent years traveling the Wakhan as a yak trader. In a land where everything was impossible, Sarfraz would be our indispensable, indefatigable fixer.

We spent several days in Kabul before heading north, shopping for supplies and exchanging dollars for bricks of Afghan banknotes at the Shari Nau market, and bicycling out to the now abandoned blue-domed Ministry of Vice and Virtue, whose Taliban enforcers had patrolled the city, whipping women for infractions as minor as revealing their ankles.

While the Afghan government has ratified treaties to improve women's rights, the country still has a long way to go to meet the standards it has set. A few days after we arrived in Kabul, the BBC and other international news sources reported that a 29-year-old woman named Amina had been buried up to her chest and stoned to death near Faizabad, the capital of northern Afghanistan's Badakhshan province, for alleged infidelity. According to the reports, 70 people from the community, including her husband and father, participated in the murder. In early May, 200 women gathered in Kabul to call on the post-Taliban government and Islamic leaders to oppose acts of violence against women, a first step on a very long, dangerous journey.

One day we visited the village of Lalander, south of Kabul, for a tribal meeting at a CAI school. It was a brand-new whitewashed, plumb-walled building amid helter-skelter mud homes. CAI schools are joint projects: The costs of construction and paying teachers are split between the CAI and the village. (Most of Greg's work is financed by private donations; the CAI receives no U.S. government funding.) With few exceptions, its schools are coed.

At the Lalander school, boys and girls were lined up in their Friday best to present Greg with wreaths of paper flowers. After the welcoming ceremony, he spoke at the jirgaÔÇöthe council of eldersÔÇöwhich met inside the village mosque. Forty stone-faced, bearded men sat cross-legged on worn Afghan rugs. Greg asked for Allah's blessing, thanked the greatness and wisdom of Allah, asked Allah to guide the judgment of the jirga. Lalander, he said, would be recognized as the most powerful village in all of Afghanistan, because of its courage to build a school that both boys and girls could attend.

Later, Greg told me that some of the men at the jirga were Taliban. “My dream is to build a school in every village from Kabul to Kandahar right to Deh Rawood, the village of Mullah Mohammed Omar, fugitive leader of the Taliban.”

As we were driving out of Lalander, Greg saw a man standing on a hillside near a pile of rocks and stopped our van. We walked over to talk to him. He was Gulmarjan's father; in June 2004, the boy had been blown to pieces by a land mine just a hundred yards from the half-completed school. According to the , leftover land mines and ordnance killed or wounded some 847 people in Afghanistan in 2004; despite determined de-mining efforts, the carnage continues.

The man told us how excited Gulmarjan had been about going to school with his younger sister. As he spoke, he raised his arms in the air, as if expecting his son, alive and whole, to drop back into them.

It took us three days to drive to Faizabad, home to the northernmost American military base. En route we passed dozens of stripped Russian tanks, most of which had been repurposed as bridges, retaining walls, storage units, and playground equipment. Even art installations: In a field by the side of the road we saw a row of three half-buried tanks sticking out of the ground like an Afghan version of Cadillac Ranch.

In Kunduz, a jovial Afghan teacher helped me order charcoal-grilled sheep shish kebab from a street vendor, and we struck up a conversation. “It took the Russians only a few weeks to take AfghanistanÔÇöjust like you Americans,” he said. “And I believe the regret began immediately.”

We spent a night in Faizabad, then drove a few hours east to Baharak, the last town in which we could buy provisions. Doug, using his avalanche forecaster's waterproof pad and clear script, was our quartermaster. A veteran of extended climbing expeditions to Pakistan, he knew exactly what we needed. He'd announce the acquired item, then mark it off his list.

“Ten kilos rice: check. Ten kilos potatoes: check. Two kilos salt: check. Aluminum pot: check. Plastic pail: check. Fifty feet nylon cord: check.”

In Baharak we stayed with Sardhar Khan, a powerful leader in the Badakhshan province. We'd been told we needed his blessing to pass through his territory and into the Wakhan.

Khan, 48, is a small ethnic Tajik with a creased chestnut face who calls himself a former warlord. One of the most feared and respected commanders in Afghanistan, he spent 15 years bivouacking in the mountains with his militiaÔÇöten years fighting the Russians, five years fighting the TalibanÔÇöbut the man I met was polite and soft-spoken. He personally laid out the silverware for a picnic in his tiny apricot orchard and told us about the school he'd built with Greg last year. It was the CAI's largestÔÇöa fortresslike structure with stone walls four feet thick and a wood-burning stove in each of the eight classrooms. More than 250 kids would be attending the school this fall.

With his wars over for now, Khan was writing poems. Greg sent me a sample of his verse after our trip:

You may wonder why I sit here on this rock, by the river, doing nothing.

There is so much work to be done for my people.

We have little food, we have few jobs, our fields are in shambles, and still land mines everywhere.

I am here to hear the quiet, the water, and singing trees. This is the sound of peace in the presence of my Allah Almighty.

After 30 years as a mujahedeen, I have grown old from fighting. I resent the sound of destruction. I am tired of war.

The next day, our fourth day out of Kabul, we reached the village of Eshkashem, at the mouth of the Wakhan Corridor. Here we met another strongman, Wohid Khan, a tall, taciturn, handsome Tajik in his early forties. As commander of the Afghan-Tajik Border Security Forces, he oversees 200 Afghan troops in their patrol of a 330-mile stretch of the Afghan-Tajik border, including the entire northern boundary of the Wakhan. Khan granted us permission to traverse the corridor, one end to the other, but he couldn't guarantee our safety once we crossed into Tajikistan. The most he could do was provide us with a handwritten note that vouched for our honorable intentions.

On either side┬áof a flat, brown valley, enormous white mountainsÔÇöthe Hindu Kush to the south, the Tajikistan Pamirs to the northÔÇörose like a mirror image. The huge teeth of these peaks, with a tongue of dirt down the middle, reminded me of a wolf's mouth. The valley disappeared into the distance, a throat of land that reached toward the steppes of western China.

The rough road that the Russian invaders had cut, following the camel path of the Silk Road, was all but goneÔÇöcovered by rockslides or swept away by floods and avalanches. Our four-wheel-drive Toyota van crept alongside slopes where we were sure we'd roll, crossed fulvous streams so high we were almost carried away. When we sank axle-deep in mud and got stuck, it took hours of digging with ice axes to extract the van.

Many of the peaks on both sides of the valley were unclimbed. Doug kept shouting for the driver to stop so we could crawl over our duffel bags, spill out the side door, and take pictures.

Back in the early seventies, stories of expeditions to the Wakhan's 20,000-foot summits generated enormous excitement. The Brits, Germans, Austrians, Spaniards, Italians, JapaneseÔÇöthey'd all come here to climb. In 1971, Italian alpinists led by Carlo Alberto Pinelli explored the eastern Wakhan's Big Pamir range and climbed three of its highest mountains, KohÔÇôiÔÇôMarco Polo (20,256 feet), Koh-i-Pamir (20,670 feet), and Koh-i-Hilal (20,607 feet). On the very western edge of the Wakhan, in the Hindu Kush, 24,580-foot Noshaq was a popular peak.

But the 1979 Russian invasion essentially put an end to Wakhan mountaineering for more than two decades. In 2003, Pinelli returned and managed to galvanize a successful expedition to Noshaq, but not a soul had summited in the heart of the Wakhan for a generation. Doug and I were itching for an ascent.

That first night in the Wakhan we slept in a khun, a traditional Wakhi home with a layered, square-patterned wood ceiling and red Afghan rugs spread over an elevated platform. The Wakhi, a tough-knuckled, wiry tribe, have ancient Iranian roots and have lived in the Wakhan for at least a thousand years. They speak Wakhi, an old Persian dialect, and adhere to the Ismaeli sect of Islam. Subsistence farmers, they use yaks to till the sandy soil and plant potatoes, wheat, barley, and lentils. The growing season is extremely short, the winters hideously harsh. One out of three Wakhi infants dies before the age of one, and women still commonly die in childbirth.

The extended family that took us in that nightÔÇögrandparents, parents, kids, aunts, unclesÔÇöwere old friends of Sarfraz, but it wouldn't have mattered; throughout the trip, wherever we stopped, we were warmly welcomed with food and a bed. An Afghan's wealth and generosity are measured by the kindness he shows strangers. Sarfraz's friends fed us ibex and brown rice, which we ate with our hands from a common plate. Several months earlier, the village school had been destroyed by an avalanche. Sarfraz spent the evening working on a plan to build a new CAI school.

The next day we continued up-valley, often walking ahead of the grinding, bottom-scraping vanÔÇöour stubborn, modern-day camel. We were passing into the Wakhan's Big Pamirs, but the valley was so deep and the mountains to either side so high, we couldn't see any peaks beyond those along the front range. We were searching for what appeared on the map to be a cleft in the left-hand wall. We needn't have worried. It was obvious the moment we saw itÔÇöa V-shaped fissure with a 300-foot waterfall crashing onto boulders.

We stopped in a yak meadow near the falls, at 10,000 feet. Sarfraz was taking the van back to Faizabad to pick up Greg and bring him out to meet us. This was base camp. We dragged out our backpacks and duffel bags, and then Sarfraz was gone. We had one week to climb the mountain.

As often happens in very remote, sparsely populated places, a man showed up out of nowhere: a Wakhi named Sher Ali, rough as a rock, with his own alpenstock. He helped clear away the yak pies and set up our tents, then stood off at a distance, staring.

“You guys know how to cook?” Teru asked, chewing on a chunk of jerky.

Doug and I looked at each other and laughed.

“Right,” said Teru. Thenceforth, Teru the photographer was also Teru the base-camp cook. He was goodÔÇödicing onions, experimenting with spicesÔÇöand each meal was better than anything us two dirtbags could have cooked up with a full kitchen. That day Doug and I reconned above the waterfall, following a steep-walled drainage up to the snow line. Beyond was a spiky wilderness of white. We couldn't see Koh-i-BardarÔÇö”Mountain of the Entrance,” in Wakhi, and the peak we hoped to climbÔÇöbut we knew it was back there somewhere.

That evening, Doug and I decided to attempt our sight-unseen peak in a single, unsupported push, while Teru waited at camp with Sher Ali.

We busted out early the following morning with so much energy we could barely keep up with our legs. We had the same pace and made swift progress. By noon we were crossing brilliant snowfields, passing beneath Teton-like granite spires. By 12:15 we were marooned.

“That's a shot,” said Doug. We heard another round fired, and we spun on our heels to see an officer with an AK-47 running our way. We put our hands in the air; he was on us, screaming, “Dokumenty! Dokumenty!”

In the space of 15 minutes, the temperature had warmed just enough for the four-inch crust to soften to the point that it wouldn't support body weight. It was like breaking through ice. Suddenly we were both wallowing chest-deep, fracturing off chunks of crust as we tried to crawl back onto the surface.

“Time to camp,” said Doug.

“Here? Now?”

“You wanna swim to the mountain?”

We tromped out a platform and spent the rest of the afternoon eating and napping and sunbathing. Up at four the next morning, we reached our 16,000-foot assault camp on the Purwakshan Glacier by ten. We dropped our packs and did a fast recon up to the base of Koh-i-Bardar to find our line: a steep couloir to a knife-edge ridge to the summit. We were back by midday and had our tent up before we once again became castaways in an ocean of snow. We couldn't take one step off our tent platform without drowning.

“We'll have to climb it entirely at night,” said Doug. We were inside the oven of our tiny two-man tent, baking to death.

Already Doug was one of the best partners I'd ever had. He was fast, funny, could sleep anywhere, in his clothes, farted like a horse, never whined, and, most important, simply loved the mountains. He was the epitome of parsimonyÔÇöcarrying the right, light gear and absolutely nothing extra, except Peet's French-roast coffee, of course.

We watched snow squalls come and go, trying to scare us, took sleeping pills at 6 p.m., got up at 11, and were crunching up the glacier before midnight. Headlamps burning, we blazed over the glacier in crampons, found the right couloir, front-pointed straight up, catwalked along the knife-edge, both fell into crevasses on the summit glacier, and swapped leads postholing right to the 19,941-foot summit of Koh-i-Bardar.

It was 6:45, 48 hours since we'd left base camp. Standing atop the summit block, we saw the whole world spread below usÔÇöjagged, pale pink, chaste. There hadn't been another first ascent in the Wakhan since 1977.

After Sarfraz and Greg met us at base camp, we drove farther into the corridor. Greg had another school meeting to attend in Sarhadd, a Wakhi village 15 miles down the road.

At the welcoming ceremony all the children lined up, looking like brilliant, unidentifiable flowers in their rags and robes of reds and maroons. The little girls wore strings of lapis lazuli, and the little boys blue Chinese Wellies. Once again Greg gave a speech to the assembled elders, but this time, for this crowd, it was different: more emphasis on the economic benefits of education, less on Allah. How one of these children right here, once they learned their three R's, could go to a trade school in Kabul and return home to fix the village tractor.

That night, when we were all in our sleeping bagsÔÇöTeru already asleep, Doug busy noting the day's weather in his journal with hand-drawn symbols, Sarfraz somewhere outside negotiating our horses for the morningÔÇöGreg and I, insomniacs both, sat with our backs against the stone wall and talked about his vision for Afghanistan.

“The U.S. fired 88 Tomahawk cruise missiles into Afghanistan in 2001,” he said. “I could build 40 schools for the cost of one of them. The Taliban are still here. They're just waiting for us to leave. You can kill a warrior, but unless you educate his children, they will become prime recruits.”

Greg pulled his scarf up around his face, looking just like an Afghan in the candlelight. He would not be coming with us deeper into the valley. There are about 550 Wakhi families in the western Wakhan, and he and Sarfraz had identified 21 villages that needed schools. “Educating girls, in particular, is critical,” he continued. “If you can educate a girl to the fifth-grade level, three things happen: Infant mortality goes down, birthrates go down, and the quality of life for the whole village, from health to happiness, goes up. Something else also happens. Before a young man goes on jihad, holy war, he must first ask for his mother's permission. Educated mothers say no.”

I asked him how the villages paid for their half of building and supporting a school.

“Often they provide labor in lieu of money,” Greg replied, “but most of the money in many Afghan villages outside the Wakhan comes from growing poppies.”

“Opium.”

“Opium,” said Greg. “It can't be eliminated. These villages are desperately poor. They're utterly dependent on this income. Eliminating opium farming will only cause more poverty and more hopelessness, which will cause more killing and more wars.”

I let it rest.

In 2004, Afghanistan produced 4,200 tons of opium, 87 percent of the world's total supply. The revenue from the illegal trade was estimated at $2.8 billion, roughly two-thirds the amount Afghanistan receives in foreign aid. In 2005, the U.S. allocated about $774 million to the effort to eradicate poppy farming in Afghanistan. Is there a better way? The Senlis Council, an international drug-policy think tank, recently proposed a radical alternative: Legalize opium for medicinal purposes.

India is already licensed by the International Narcotics Control Board, an independent watchdog group that monitors the trade of illicit and medicinal drugs, to grow opium and produce generic pain medication for developing nations. Afghanistan could do the same. The cost of creating such a program has been estimated at only $600 million. Ideally, the farmers would get cash, the drug lords would get cut out, the developing world would get more pain-relief medicine, and the major demand for the global traffic in heroin could be drastically reduced.

It's a compelling strategyÔÇöaccepting the reality on the ground rather than fighting itÔÇöand it's exactly how Greg operates. He doesn't get caught up in moral abstractions; he focuses on what works, no matter how tortured or contradictory.

Sarhadd, roughly halfway up the Wakhan Corridor, is at the end of the road. From here all travel would be by foot or horseback. We had 80 miles in front of us to reach Tajikistan.

On a cold, windy morning, Sarfraz, Doug, Teru, and I left Sarhadd with four packhorses and four Wakhi wranglers. For two days we hiked along the bottoms of immense canyons, in the shadows, jumping boulders, fording side streams, imagining Marco Polo doing the same thing. We climbed two small passes to escape the canyons and reach the upper Wakhan settlement of Langar and Khan Bibi's grim stone hut.

From Langar we walked to Bazai Gonbad, a Kirghiz burial ground consisting of a dozen domed, chalk-white mausoleums. Beyond Bazai Gonbad, the Wakhan widens dramatically. The valley is too high for farmingÔÇö12,000 feetÔÇöhence the eastern Wakhan is inhabited primarily by Kirghiz nomads. In general the Kirghiz are wealthier and healthier than the Wakhi, although ever since the borders were closed in 1949, there has been a symbiotic relationship between the two peoples. The Wakhi need animals and the Kirghiz need grain, so they barter.

The Kirghiz are cowboys, and Sarfraz, a great rider himself, managed to get us saddle horses. Teru, the New Yorker, was the most natural cowboy among the Americans, followed by Doug, who is originally from New Jersey. I grew up in Wyoming working on ranches and can't ride a horse to save my life.

The upper Wakhan is one of the last refuges for at least three endangered speciesÔÇöthe snow leopard, the Himalayan wolf, and the Marco Polo sheep. All are still hunted by the Kirghiz. (We saw wolfskin coats for sale on Chicken Street in Kabul and were told the pelts came from northeastern Afghanistan.) In a heavy-snow winter, the Kirghiz hunt snow leopards and wolves that prey on their sheep, and sometimes even on children; they hunt the sheep for food. But change is coming: Biologist George Schaller, vice president of science and exploration at the New YorkÔÇôbased Wildlife Conservation Society, has been inventorying Marco Polo sheep in the area since the 1970sÔÇömost recently visiting in 2004 and 2005ÔÇöand he's campaigning to make the entire region a protected international park.

One evening we stopped in a Kirghiz camp called Uchkali, “Place of the Ibex,” where there were nine families living in nine yurts and an untold number of goats and sheep and yaks. Kirghiz lives are interwoven with the lives of their animals, and they subsist almost entirely on red meat, milk, and yogurt. Although they speak a Turkic dialect, their ancient ancestors may have been Mongols. After welcoming cups of tea, the old chief, a man named Yeerali, set before us a battered cardboard box. Inside the box was a gas-powered generator.

Yeerali had bought the generator the previous autumn, along with several gallons of gas and a box of electrical supplies, and brought them here by horse in hopes of having lights during the long, snow-buried winter. Of course the generator broke soon afterwards and the camp spent another winter in darkness.

We were Americans, were we not? Visitors from the land of machines. Certainly we would fix the generator.

After having been given so much by the people of the Wakhan, it was our chance to give something back. Besides, we were on the spot. Doug and I took up the challenge.

First we carefully examined the little beast, talking back and forth in a professional tone, making a good show of our diagnosis. Then we got out our multitools and went to town. We fiddled with the gas mixture and the throttle spring and the adjustment screws and the choke lever and the spark-plug gap.

The machine was no more complicated than a lawn mower, but the gaze of the entire camp was on us. After we'd done all we could possibly think of and then some, I yanked on the pull cord.

Nothing. The Kirghiz's disappointment was palpable.

We fiddled some more, I pulled the cord: a cough. Their eyes lit up. More adjustments, I pulled the cord, and the little engine that could roared to life.

Doug and I were instant heroes. Yeerali ordered two men to kill the biggest sheep of the herd, which they did forthwith, cutting its throat and skinning it right there in front of us. While the various parts of the sheep were being cooked, Doug and Sarfraz and I dug into the box of electrical supplies and proceeded to electrify the camp, stringing wire and lights to the nearest yurts as if they were Christmas trees.

When the platter of food arrived, we sat down beneath the abundant light of a single dangling bulb.

Now, there's something special about Wakhan sheep, a Central Asian breed called turki qoey: They have two distinct camel humps of fat on their behinds. Like whale blubber to the Inuit, sheep-ass fat is a delicacy to the Kirghiz.

Two large lumps of steaming ass sat in the middle of the platter, surrounded by the boiled head and testicles.

Doug and I glanced at each other and, without hesitation, sprung open our belay knives, cut off large slices of greasy butt fat, and plopped them into our mouths.

“Not bad,” said Doug. Then he cracked open the sheep's head and took a bite of the hot, soft cheek, and I ate one of the big, slippery testicles.

We traveled by horseback for two more days across the upper Wakhan, stopping in Kirghiz nomad camps along the way. We spent our last night in the Wakhan in Urtobill, a community of four extended families. Together they'd pooled their resources and bought Chinese solar panels, a car battery, a TV, and a video player. That evening we sat with them inside a Kirghiz utok, or community house, and watched their only video: a grainy 1975 documentary called The Kirghiz of Afghanistan.

The next day, we galloped up to the Tajikistan border, which was marked by a tangled, partly downed barbed-wire fence. Nobody was there. Just more open brown country.

It was the end of the road for Sarfraz. We dismounted and took pictures. Sarfraz had become a friend, and we were going to miss himÔÇöjust how much, we had no idea. We hugged and shook hands, and then Doug and Teru and I walked into Tajikistan.

We were Americans, were we not? Visitors from the land of machines. Certainly we would fix the generator.

We followed a washed-out tank track due east along the barbed-wire fence, passing two tall, abandoned guard towers. After ten miles we still hadn't seen a soul. Up on the hill to our left were another guard tower, some tanks buried in tank pits, and some buildings, but the place appeared deserted, so we kept going.

A quarter-mile past the outpost, we heard a pop and a zing. “That's a shot,” said Doug. He was brilliant.

We heard another round and spun on our heels to see an officer with an AK-47 running down the hill toward us. We put our hands in the air. In seconds the officer was upon us, screaming in Russian and waving his rifle in our faces. “Dokumenty! Dokumenty!“

He was the spitting image of a young Robert De Niro in The Godfather: Part II, and seemingly just as volatile and unpredictable. I could see his finger trembling on the trigger.

We slowly handed him our passports, along with the note from Wohid Khan.

“Wohid Khan, Wohid Khan,” we said in high, choirboy voices. The name seemed to register.

He marched us to the base. All the buildings were abandoned but one. We were taken inside, past a small kitchen, into an even smaller office, the door closed behind us. A metal desk, a shelf with Russian military books, a couch. We sat on the couch while Vito Corleone laid his AK-47 on the table and allowed us to see that he was also packing a sidearm. He looked like the kind of guy who was waiting for us to do something stupid so he could blow us away right there.

Eventually he got up, opened the door, and motioned for us to step out. We were taken to a little kitchen and served tea and cookies. In the next room we could hear Vito calling his superiors. Two hours later another officer arrived.

“Welcome in Tajikistan,” he said happily, then shook our hands. He looked like a bearded Antonio Banderas.

We thought he actually spoke English, but he didn't, so the interviews took a long time. Vito and Tony had some kind of comic-book interrogation manual that they used to extract information from us.

Were we Al Qaeda? Were we Taliban? Were we CIA? Were we drug smugglers?

We answered no to all of the above.

What were we, then?

Tourists.

Tourists. Tourists who walked all the way across the Wakhan?

Yes.

We showed them our route on the map.

That is not possible, they said. No one has ever crossed this border.

We know. That's why we're here.

Vito and Tony were dismayed. They decided to go through the contents of our backpacks, one item at time. Toothbrush, dirty underwear, unwashed bowl. They made a complete inventory, but it was obviously a letdown. No guns, no drugs, no secret documents. Had we been real spies or at least drug smugglers, Vito and Tony would have been promoted and could have gotten out of this shithole outpost. On the other hand, since we really were three stupid American tourists, they could chill out.

That night our interrogators gave us their own bunks while they slept on the hard floor of the office.

I was so thrilled I couldn't fall asleep.

“We did it, guys,” I whispered. “We crossed the Wakhan!”

“And now we're under arrest,” said Teru.

“I would call it temporarily detained,” said Doug.

It took us five days┬áto work our way through the red tape. We were transferred north through TajikistanÔÇöin beat-up cars that ran out of gas, and on footÔÇöone military base to the next, one interrogation to the next. We were put up in rooms, heated by small piles of burning sagebrush, with Soviet pinup girls on the walls. We were served platters of Marco Polo meat and treated like visiting dignitaries, then informed we were going to prison. We played volleyball with bored boy-soldiers, then were told we were dangerous spies.

Back in Afghanistan, word of U.S. interrogators at Guantánamo torturing Muslim captives and flushing the Koran down the toilet had ignited anti-American riots throughout the country. Backing out of the Wakhan, Greg had been caught up in the conflagration and was laying low in a hotel in Faizabad. Still, he managed to get a sat-phone call to the U.S. embassy in Kabul, informing them of three errant Americans.

We were released into the custody of U.S. embassy officials, who drove us to the Tajikistan capital of Dushanbe. The moment the doors closed on the bulletproof embassy Land Cruisers, we were home. ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° it was Tajikistan; inside it was America. We drove to a fancy hotel listening to Van Morrison, eating Pringles, and drinking Coke.

Mark Jenkins, who writes the Hard Way column, lives in Laramie, Wyoming. Teru Kuwayama is an ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° contributing photographer.