Sure, the men and women who take us skiing, fishing, rafting, and climbing get to work in beautiful country. But they also have to deal with 16-hour days, dirty diapers, beach sex, rogue clients, hangovers, low pay, bear encounters, and love affairs that aren't always a good idea. Don't believe us? Just ask them. (And check out the responses to our anonymous survey of 500 guides to get a glimpse of the greatest tips, worst clients, and occasional murder threats of the job.)

Everybody Starts at the Bottom

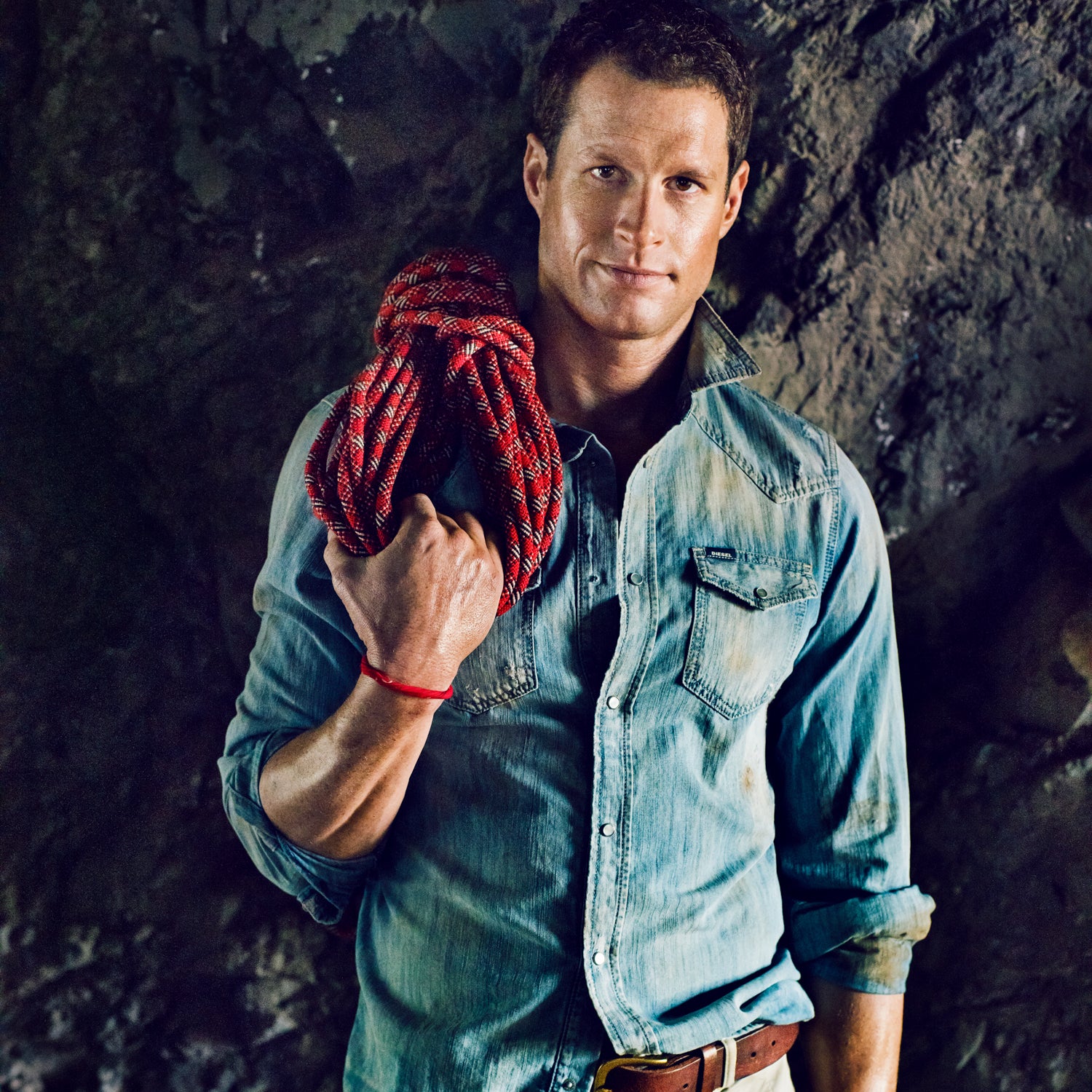

Garrett Madison, 36

Owner of ; guide on the Seven Summits and other peaks

I was 20 when I was first hired at . Back then they held guide tryouts. There were maybe 90 of us, and we were all competing for the same ten jobs. We had to get up and tell everybody why we thought we should be hired, which was one of owner Peter Whittaker’s tests. Another was the Death March, a one-mile, 1,500-vertical-foot run from Paradise up to Panorama Point. They said, “It’s important to finish near the front of the pack.” They had one of their stronger guys lead us out of the parking lot and up the hill through the snow. He took off at 100 percent, and it was a struggle to keep up. Then we got to the halfway point: their strongest guy had hiked up earlier in the day and was waiting for us. He dropped everybody. I don’t think the results even mattered; it was just the Whittaker way. Once I was hired, I made $60 per day, and sometimes it was a 24-hour day. We worked two to three weeks in a row leading two-day summits. We would take a group up, come back down, get the next group, and summit again. I once made five Rainier summits in a week. We called them yo-yos. We barely slept. I’m not sure I could do it now.

It’s the Guide’s Job to Deal with the Sh-t

Doug Grady, 44

Former guide in the Andes and Himalayas for

I was on a two-week trip guiding on Cayambe, the third-highest mountain in Ecuador. It’s 19,000 feet. There was weather up high, a snowstorm, and we were getting battered. So we hunkered down on the lower glacier for a few days. When that happens, all you can do is sit, eat, talk, and shit.

A guide is always keeping an eye out for whether people are warm, dry, well fed and hydrated, and having fun. You also want to make sure they’re going to the bathroom regularly.

I noticed that one woman—she was attractive and always really put together—wasn’t. Well, this woman’s tentmate came to me and said, “I don’t know what’s going on, but my tent smells like shit.” Right then I knew something was wrong.

So I waited about an hour, to give the tentmate some plausible deniability, and then went to talk to her. I said, “Are you warm? Are you dry? Are you having normal bowel movements?”

“Yes,” she said.

“Where have you been using the latrine?”

“Well, I’ve been taking care of it on my own.”

I kind of paused and said, “What does that mean?”

She said, “I brought these Depend adult diapers so I could go in my pants and then take them off and put them in my backpack.”

I don’t know how long I paused before I said, “You have to stop taking shits in your own pants.”

As you can imagine, it was a pretty foul scene in that tent. And, being the guide, I was the one who had to take care of the diapers.

There’s No Such Thing as Privacy

Angelisa Espinoza, 37

Cycling guide for

The only way to deal with the craziness of guiding 24 hours a day is to shut off everything personal. When I’m on a trip, I don’t talk to my family, I don’t pay bills, I don’t deal with anything that’s not right in front of me. I’m taking care of people psychologically and logistically. You spend every day with them. That’s a lot of time, although it’s also the greatest part about the job—the people are usually lovely. But you never get a break. Wherever I guide, there’s a house for the staff. It’s like The Real World: everybody has a shared living space. Your office is there, too, and those people are your social life, because you’re there alone in Hawaii or Thailand or wherever.

When you’re young, it’s exciting. You don’t have many expenses, and you get to travel to all the places you’ve always wanted to see. But when you’ve been guiding for a long time, you start praying for privacy and time off. Now I just want to be at home with my man. I don’t really care if I go to New Zealand or Vietnam, because I’ve been there.

The Perfect Prank Requires Perfect Timing

Chris Glatte, 46

Former river guide in Oregon and Idaho

On the last day of a Rogue River trip, in Oregon, we always stayed at Decision Rock, and we always had bear trouble. So for years we would stack rocks nearby to throw at them. You’d hear other camps banging pots and pans, and you knew they were hosed. But the bears would never mess with us more than once, because of the rocks.

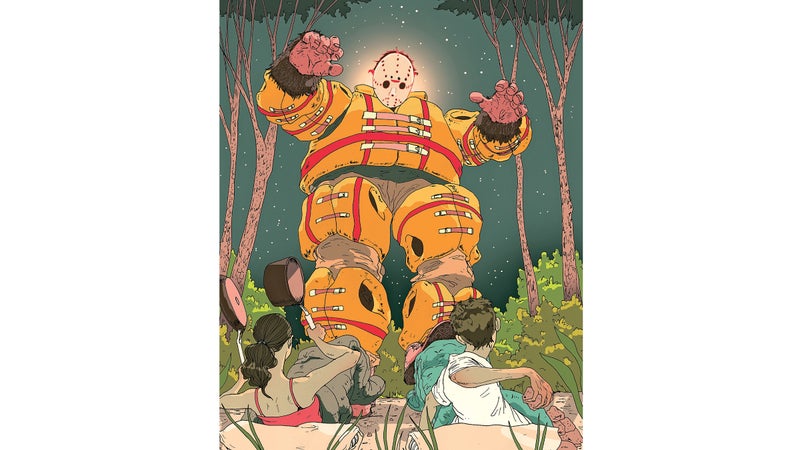

The summer of 1998 was my last season as a guide. Before we put in on my last trip, I went to a costume shop in Grants Pass and asked for a bear suit. They didn’t have one, but they did have a gorilla. So I rented that and packed it in my drybag.

When we got down to Decision Rock, the clients all left to camp above the river. As we got ready for bed, I told the other guides, including my brother, Hayden, and his future wife, Margie, “Hey, the last time I was here there was a bear cub, and I don’t want to hurt the cub, so I think we should bang pots and pans tonight instead of throwing rocks.”

So I got all these pots and pans and put them next to everyone’s heads. Hayden said, “I’m not doing that. It doesn’t work.” So he stacked up a bunch of baseball-size rocks beside him.

We went to bed, and I set my alarm for two o’clock in the morning. When the alarm went off, I snuck away. I took several life jackets, and I strapped them on all over—around my shoulders, like a diaper, everywhere. Wearing all that with the costume over it, I was huge.

I ambled down to the river on all fours, and I put my hands on the table and knocked stuff around. I was making all this noise: “Grrr, grrr.” Margie woke up and elbowed my brother. “Hayden, it’s a bear! He’s right there!”

Hayden got up, pretty groggy, and tried to focus on what he was seeing. When he reached back and grabbed a rock, I stood up and started running at him as fast as I could. He was tangled up in his sleeping bag, and I jumped through the air at him, but he got his feet up in time. So instead of landing flat on top of him, I landed on his legs, and he started jackhammering me in the gut.

Meanwhile, I was swiping him in the face, trying to claw him with the rubber gorilla hands. He was screaming in terror. I looked over and saw Margie, who was beside me, with her pot in her hand, and she was banging the pot, trying to scare me while I was mauling Hayden. When I saw that, I lost it and started laughing so hard I rolled right off him.

At this point, all the guides were awake. My brother was hyperventilating. He told me later, “As I was kicking you, I was thinking, He’s kind of soft for a bear.”

A coda to the story:

After that, I circled a bunch of kids from New York City who were on the trip. They all woke up and stared—not making a move.

In the morning, one of the kids said, “There was a bear last night!” And soon all of them were telling stories about what they saw.

But one of the kids, Brian, wasn’t saying much.

“Brian, did you see the bear?” I asked.

And another kid said, “Don’t ask Brian. He thought it was a gorilla.”

You Can’t Predict What Will Go Wrong

Peter Grubb, 57

Owner of

On one section of Idaho’s Lower Salmon River, we do a lot of family trips. It’s warm, intermediate whitewater with plenty of big beaches for camping. One year I was rowing that stretch and I had a family in my boat—a mom, a dad, and a couple of kids, maybe 10 and 12 years old—and I saw something on the beach but couldn’t make out what was going on. As we drifted, I said, “It looks like they’re playing Twister.”

As we got closer, the details came into view: There was a naked guy balanced on his hand. There was a large naked woman on top of him. And let’s just say there was another guy involved, too. I turned my boat so that the family was facing the opposite shore, trying to edit their view. But it was no use.

When the three people saw us, they broke apart. But instead of hiding, the woman ran down to the water’s edge. I was as far away from her as you can possibly get on the river and still be wet, but she kept yelling, “Come on over! Come on over!”

That particular section of river has a lot of interesting geology, so I started talking about basalt flows. We ignored her until she went back and resumed her activities with one of the naked men. But the second naked guy, he got on an ATV and started doing donuts around the couple while they were going at it.

We still call that spot Twister Beach.

Everything Is the Guide’s Fault

Chris Dombrowski, 39

Fishing Guide in Montana; author of Body of Water

On my first day, I took this couple down the Big Hole in Montana. The husband had a fly-rod outfit, but the woman had nothing. I had only one combo, but I said, “You can borrow my rod and reel for the day.” We fished through the morning and stopped to eat lunch on a high bank overlooking this nice run, so we could see if fish were rising. We got back in the boat after lunch and pulled away from the bank, and I said, “OK, cast to this left bank near the grass.” And the woman said, “Where’s my rod?” And I said, “What do you mean?” And she said, “Well, I just leaned it against the boat at lunch.” I started booking it upstream to see if the rod was still there, but of course it was gone, swept away in the river.

When I got back to the fly shop, I complained to my boss. He said, “If a guy falls in the river because he’s drunk, it’s your fault. If a woman gets lost in the woods while she takes a piss, it’s your fault. And if someone loses your rod, it’s your fault.” In our business, there’s a lot of truth in that.

A True Professional will do Anything for The Client

John Race, 46

in Alaska

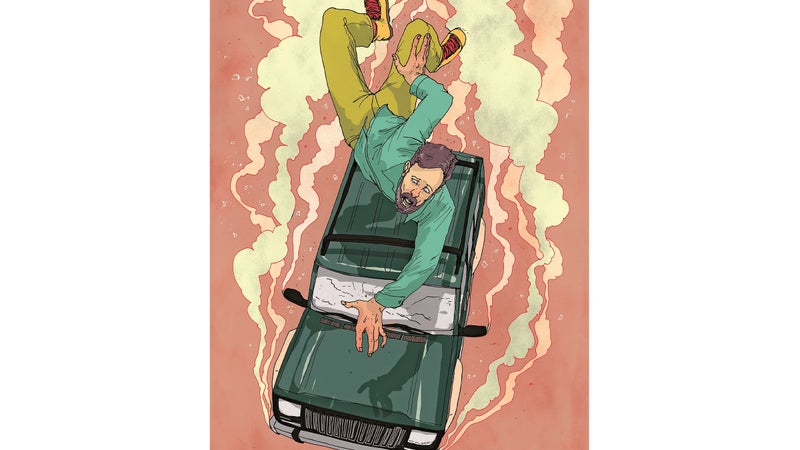

In 1992, I led my first trip on Denali. I was 23, and my assistant, Matt Belson, was 21. When we met our clients at the airport in Anchorage, you could tell they thought we’d be older. “Where are the guides?” they asked. “That would be us,” I said. So I was eager to impress them. But when our driver showed up, she had a van that was too small for our group and all our gear. Behind her were two Jeep Cherokees driven by a couple of Germans. She explained that the larger vehicle she usually drove had caught fire earlier that day, when she had been driving the Germans to Anchorage to rent the Jeeps for a trip to the north side of Denali National Park. She convinced them to transport our group to Talkeetna, and in exchange, we’d cover some of the rental costs.

We climbed in and drove all the way through Anchorage in bumper-to-bumper traffic before Belson remembered that we had forgotten to grab the dry food at the airport. We told the Germans that we had to turn around and drive all the way back. They were pissed, but they complied. We got the food and headed back out of town. Our usual arrangement was to then stop in Wasilla to pick up fresh food items. Nobody had mentioned this to the Germans, but again they complied. I went in to shop and was collecting 12 pounds of butter when Matt ran up and told me that the Germans were leaving. All our gear was in those cars, so I ran outside and saw the Jeeps hit the main highway.

I sprinted across the parking lot, across a ditch, and onto the road waving my arms. I locked eyes with the older German man driving the first Jeep. Instead of stopping, he accelerated. I jumped into the air just before he ran me over. I hit the windshield, rolled onto the top of the car, and grabbed the roof rack right before I went off the back. When the German slammed on the brakes, my group surrounded the car, dragged him out of his seat, and pushed him to the ground. Then I grabbed one of my clients, stuck him in the driver seat, put the old German in the back, and told the new driver to take the group to Talkeetna and make sure our gear was OK. Then I finished my shopping.

Nothing Beats a Client with a Good Attitude

Cameron Scott, 37

in Colorado and Oregon

One day I picked up the clients of a retired guide in Basalt, Colorado. The trip had three generations of women in one family—a grandma, a mother, and a daughter. Another guide took the mother and daughter, who was maybe 13. And I had the grandma, who had fly-fished with us forever. She was one of those women who found fly-fishing in the 1970s and kept doing it even though it was a very male-dominated sport. Now that she was older, she’d gotten really severe dementia. But she retained that love.

It was a mid-August Colorado day in 2012, the monsoons had just quit, and it was sunny and warm. The green drakes were hatching in the afternoon. The water out of the dam was cold enough to hurt your hands.

We were on the Fryingpan—a magnificent fly-fishing river—and there were four billion fish out there. The grandma would catch one, bring it in, get this huge grin, and comment on how beautiful it was. Then we’d let it go. And not 20 seconds after, she’d say, “Cam, when am I gonna catch a fish?” Just as if she hadn’t caught one yet. She remembered how to cast. She remembered my name. She remembered the Fryingpan. And every time she caught a fish, she was mesmerized. But whatever it was about her dementia, she couldn’t hold on to that moment. It was almost like the excitement was so pure, she couldn’t get back to the present afterward.

This went on for about four hours. Finally, it was the end of the day, and she said, “Cam, I really had a great day. But I really wanted to catch a fish.” And I was crushed. I wanted nothing more than to have her know that she caught a fish.

But the thing was, she had such pure excitement each time she caught one. Rarely are adults that excited. So often they catch a fish—even a big fish—and all they want to do is catch another one. But with her, I got to see the excitement of that first fish over and over again.

Never Assume the Client Has a Clue

Scott Schell, 42

Former mountaineering guide with

One guide I know had a Japanese client who was a novice skier. They met in the morning and went out, but the client was really suffering. The man spoke only Japanese, so the guide couldn’t understand what the problem was. The client just kept pointing at his boots. Finally, the guide sat the man down in the snow to look at his feet. Now, this client was just a little guy, maybe five foot six. But the guide noticed he was wearing these massive ski boots—maybe size 14. “We’ve got to take these off,” the guide said. “There’s no way they should be hurting so bad.” He unbuckled the boots and found the problem: inside, the guy was still wearing his leather dress shoes.

Making the Job Your Life Means Making Compromises

Dave Hahn, 53

Mountaineering guide for RMI

I’m on the road eight months of the year, and that’s good and bad. Buying a house was smart, in terms of establishing a base, but now I have something to miss. Before, what did I miss? My car? The toughest thing for me is packing up for Mount Everest in the spring and missing the end of ski-patrol season at Taos, New Mexico, which is the funnest time. I go to ten weeks of cold, nasty, mean Everest weather just as the flowers are pushing up and the birds are singing in my yard. It’s different when you’re prepping for a personal climbing goal, but I’m leaving to go to work, even though I’m excited once I get there. I’m not whining. It’s just what happens when you turn something you love into a job.

Expedition guiding is something of a selfish pursuit. If you’re pining for someone at home, you probably won’t be a good guide. I feel like it’s wrong to repeatedly leave someone behind to go on long expeditions. You’re putting them through hell. I think the only way it can work is if the person you’re involved with is just as into doing their own thing while you’re off doing yours. Personally, I’ve never had any grand scheme to avoid marriage and family. I figured I’d do it all when I grew up, but growing up has turned out to be time-consuming and tedious.

Contributing editor Christopher Solomon wrote about skiing in British Columbia in November.