Their friends were dead or starving. Parrado’s mother and sister had died in the crash. Finally, after 61 days in the Andes, 23-year-old Nando Parrado and 19-year-old teammate Roberto Canessa left the plane’s wreckage and trekked for ten days over seemingly impassable 14,000-foot peaks to find help. The two men’s heroism was documented in the 1974 book Alive, by Piers Paul Read, and in the 1993 film of the same name, in which Parrado was portrayed by Ethan Hawke.

Exclusive Preview: Miracle in the Andes

to read an exclusive preview of the ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═° May feature article by Nando Parrado.Nando Parrado

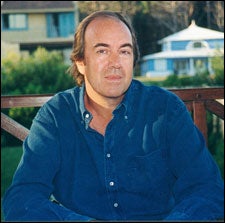

Nando Parrado in the backyard of his summer home in Punta del Este, Uruguay. December 2005.

Nando Parrado in the backyard of his summer home in Punta del Este, Uruguay. December 2005.Today, 56-year-old Parrado is a Uruguayan television personality, amateur race-car driver, and successful businessman. This March, he returned to the place in the Andes that changed his life. With him were his wife, Veronique, and two daughters, Ver├│nica, 24, and Cecilia, 21. Jason Stevenson talks to Parrado about what he took with him from the Andes—and what he left behind.

║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°: How did you reach the site of the plane crash on this most recent visit?

PARRADO : It’s very isolated. You have to fly to a small city in Argentina, San Rafael. From there you drive three hours into the mountains, until the road ends. You get on horseback and you climb two days up to 12,000 feet—then you are at the site.

This was the first time your family came with you to the site. Why now?

For many years they all thought, “Why? Why should I go to the worst place in the world, where my father or my husband had suffered so much?” But after they read my book, they decided they should go to the place where they were created. Because if I hadn’t fought that hard, my children wouldn’t be alive today. It was very emotional. One of my girls, Ver├│nica, got altitude sickness, and I asked her if she wanted to turn back. She said, “No way. I want to go there. You suffered, and it doesn’t matter if I suffer. I have to see the place.”

It must have been intense.

I think their embraces told more than a million words. They stood at the same place I stood. And they were amazed at the decision to climb those rocks and big walls. They asked, “How could you have done that?” But when you are pressed by death, you can do things that you think are impossible.

This wasn’t the first time you’d been back.

This was my tenth trip. I went with my father nine times. He has been up there 17 times to visit the graves of my mother, Eugenia, and my sister Susy, who died from the crash. Starting in 1974, he went 17 straight years. He’s 89 years old.

You mention in your book how often you thought of your father, how he was your main source of strength during the ordeal.

He was in my thoughts, very much, every step. Because at the time, he was the only thing I had to look up to. Now I have my family. My wife and my daughters are my whole life.

It must have been difficult to get your life back on track. What was it like returning home after the accident?

There’s a very drastic difference between me and the other survivors. I cracked my head open in four places, I was in a coma for three days. I lost my mother, my sister, and my two best friends. When the others were rescued, they went to the hospital and everything was finished. Their families were there; their girlfriends were there.

It was different for you.

When I got back, everything started. I had lost half my family. I didn’t have anything. My real Andes started afterwards.

People might think that this experience would deter you from being adventurous, but you’ve only become more daring.

I’ve raced cars for 25 years—it’s part of my life. I go to France in July and will race a Matra M650, which has a 550hp V-12 engine and goes around 230 mph. My father taught me how to drive very fast—he was the president of the Uruguayan Racing Drivers Association. I also love to sail, and I ski, though I’m not very good, because we live in a flat country. But I love the mountains.

What about mountaineering?

I have a sexual attraction to ice axes and crampons. Every time I go to an REI store, I let my hands slide through them. I think how much these tools would have saved me in time and danger during the trek.

What does your wife think of this?

She tolerates it, but she tells me never to bring them to bed. (Laughs)

You seem to have a great life. After all these years, why did you decide to write your story?

When I go to conferences around the world, people tell me, “You should write about what you speak.” And then my wife pushed me. I decided I could write a book for my father too, before he died. That would be the best present that a son could give to his father.

Was there anything about Alive the book or Alive the movie that didn’t get it right?

They’re both very accurate. But having lived through that misery, I don’t know if a reader or people sitting in a movie theater can really comprehend the cold that burns like acid and never ends, and the fear that you have inside. I think that what people see as courage, it’s actually fear. I was so afraid, every minute. This wasn’t heroism, or adventure. This was hell.

It sounds like you discovered a lot about yourself.

I have learned that the only thing that matters is affection. All of us would have given whatever we earned in a thousand lives only for an embrace of our family. We learned so much through sorrow and pain, so whenever I look at my girls walking, or eating, or playing with the dog—I am very happy. That is my happiness now.

It must be strange to look back 34 years later. Any words of wisdom?

My father told me once, “You shouldn’t look back.” There’s no way that you can modify the past. You can modify the future through your actions. So go live your life, and follow your heart, and do what you think is best.

Look for an exclusive excerpt of Miracle in the Andes (Crown, $25) in the May issue of ║┌┴¤│ď╣¤═°, on newsstands April 11, 2006. The book will be on sale starting May 9, 2006.