This story update is part of the ���ϳԹ��� Classics, a series highlighting the best writing we’ve ever published, along with author interviews and other exclusive bonus materials. Get access to all of the ���ϳԹ��� Classics when you sign up for ���ϳԹ���+.

When the 70-foot longliner Andrea Gail was lost off Canada’s Grand Banks on October 29, 1991, Sebastian Junger was living in Gloucester, Massachusetts, the boat’s home port, working as a tree climber to support his freelance writing career.

The Andrea Gail was on day 40 of an extended commercial swordfishing trip when three powerful storms converged on the Northeast. Data buoys measured waves as high as 100 feet, and the boat was hit with winds measuring 80 knots (92 miles per hour). The night before the storm, on October 28, Andrea Gail’s captain, Billy Tyne, radioed to area fishermen, “She’s coming on, boys, and she’s coming on strong.”

The Andrea Gail’s six-man crew—Tyne, along with David Sullivan, Bobby Shatford, Alfred Pierre, Dale Murphy, and Michael Moran, all young men in their twenties and thirties—didn’t make it home. As one local fisherman would tell Junger, “Whatever happened happened quick.”

The Andrea Gail’s emergency beacon washed ashore that November on Sable Island, off the coast of Nova Scotia, but the boat was never found. The crew left behind five children among them, and the entire small town mourned the loss.

The Original Story of ‘The Perfect Storm’

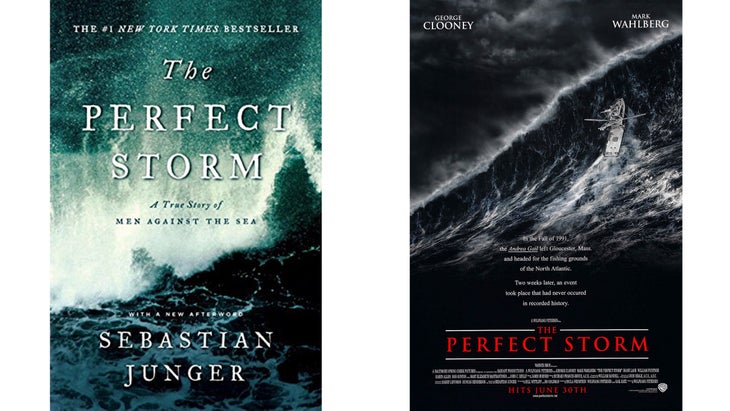

Six young men set out on a dead-calm sea to seek their fortunes. Suddenly they were hit by the worst gale in a century, and there wasn’t even time to shout.Junger was captivated by the event—and eventually the world would be as well. He spent months interviewing fishermen and surviving family members to write “The Storm,” which ran in the October 1994 issue of ���ϳԹ���. The article grew into the 1997 bestselling book and the , starring George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg. The legend of the Andrea Gail fueled a fascination with the dangerous work of commercial fishing that led to shows like Deadliest Catch. Since the Andrea Gail’s demise, the industry has only become more perilous, as violent storms have pushed farther into the north Atlantic Ocean and dwindling catches have meant smaller profits and smaller crews doing the same work. Since 1991, 11 more Gloucester fishermen have been lost at sea.

The dignity and adventure found in dangerous work are themes that have stayed with Junger throughout his writing career. His war reporting from Bosnia and Afghanistan informed his next books, �����Ի� . And Restrepo, the documentary he made with the late photojournalist Tim Hetherington about a year in the life of a U.S. Army platoon in Afghanistan, was nominated for an Academy Award in 2010. His most recent book, , about a months-long walk along the railways of Pennsylvania, came out in spring 2021.

Junger spoke with contributing editor Elizabeth Hightower Allen by phone from his apartment in New York, where he lives with his wife and two children.

OUTSIDE: Let’s rewind. You were working as a tree climber when the Andrea Gail went down?

JUNGER: I was 29. I was living in Gloucester and trying to make my way as a freelance writer, basically blundering through my twenties and wasting an enormous amount of time. I had this job as a climber for tree companies. I’d be topping out pine trees, 80 feet in the air. It was all the right mix of scary, chainsaws, and heights—things that could kill you if you did it wrong. But it allowed me to write. And it gave me a dose of reality. I got a little careless with the chainsaw and whacked the back of my leg. I was up in the tree on a rope, with a running chainsaw, looking down at my Achilles tendon. Thank God I didn’t sever it, but I laid it open. I was limping around Gloucester recovering when this huge storm hit. A Gloucester boat, the Andrea Gail, was presumed lost a thousand miles out to sea.

Had you written for many magazines at that point?

It would have been my first national magazine piece. I’d been thinking about writing a book of essays about dangerous jobs. I was very enamored of John McPhee, and I wanted to do a collection of essays on forest firefighting, drilling for oil, working as a war reporter—basically all the stuff I wanted to learn to do myself. So I sent ���ϳԹ��� what I thought of as the first chapter of that book: 15,000 words on the Andrea Gail. Hampton Sides, who was an editor at the magazine then, worked with me on a new shorter version that became “The Storm.”

So you were approaching people in the fishing community without an assignment saying, “I’d like to do a book on this.” I imagine that was hard.

The family of one of the crew, Bobby Shatford, ran a waterfront bar, the Crow’s Nest, that was the center of the fishing community. His mother, Ethel Shatford Preston, was the bartender. I walked into that bar, and she didn’t know me from Adam, and I started asking questions about her son who had died. She didn’t throw me out. She heard me out. Had she not done that, the book wouldn’t exist. I would have been shown the door.

A lot of that was because, I think, I was someone who was also “working for a living.” I would go into the bar covered in sawdust from a tree job, dirty from a day’s work. There are two kinds of jobs: the kind where you shower the morning before you go to work and the kind where you shower at the end of the day after you come home. I had the latter. I have no idea, but I think that probably allowed her to at least give me a chance.

What did the community think about the magazine story?

They loved it. They put it up on the wall at the Crow’s Nest. That said, it was hard to know if it made a larger splash beyond Gloucester, because the internet didn’t exist at the time. I think the story got some attention, but the earth didn’t stop. I didn’t necessarily think that the book would be a big hit, either—I knew I was writing something somewhat journalistically novel, but I wasn’t fool enough to think it would be a bestseller. Fast forward ten years, and everyone was obsessed with dangerous jobs—Deadliest Catch, all of that—but not in 1994.

When you did write the book, you found yourself in deeper water—that the central narrative, what actually happened to the Andrea Gail, was essentially unknowable.

While the years were slowly turning in the literary world about whether I could sell that book, I went off to Sarajevo to learn how to be a war reporter. I’d been in Bosnia six months when my agent faxed me in Zagreb and said, “Congratulations. I sold your book proposal for $35,000. Now you’ve got to come home and write it.”

I thought, How do you write a whole book when the central drama of the book is just a huge question mark? The boat disappeared. How do I do that without fictionalizing? And then I read The Hot Zone by Richard Preston. He did this amazing thing where he was writing about things that he could not personally have known either. About the first character to come down with Marburg virus, he writes, maybe he was walking home, maybe he looked at the sunset. It had an inherent tension to it because the reader realizes, Oh my God, we don’t know. And there’s no way to know.

All of a sudden, what seemed like a deficit of information became a dramatic asset: the Andrea Gail could have done this, or maybe more probably, according to other fishermen, this is what was happening. When I started writing it in that way, I got really excited. The dread of impending failure finally left me and, and I thought, I can do this. This is a cool way to write a book.

Of course, it did become a monster hit. The Perfect Storm has now sold more than five million copies worldwide. How did that affect Gloucester?

I think people in town really felt like the industry and the town were getting the credit they deserved; these are rough, working-class guys and working-class families, and they’re not used to a lot of love or even appreciation. Suddenly being a fisherman was cool, particularly with the movie. The bookstore was selling the book like crazy, and it spawned a cottage industry in town. There was a guided Perfect Storm tour—you’d have a drink at the Crow’s Nest, talk to the guys loading the ships with ice, and go to the bait shop. They weren’t banking millions, but it created something. It was a pride of place and pride of job—recognition for a very, very hard, brutal, dangerous job.

Did you keep in touch with many of the families?

I was enormously fond of Ethel Shatford Preston, whose family ran the Crow’s Nest. She was this powerful mother figure for a lot of people in Gloucester. She had such a big heart. We became really good friends. When she died of cancer in 1999, the family asked me to speak at her memorial.

I did have one regret about Ethel, however. She smoked quite a lot, and I described her—I’d never written a book before, and it never occurred to me that the people you write about will actually read the book—as gray-faced. She loved the book, but at one point she was like, “Gray-faced, huh?” And I thought, Oh my God. Of course, you read that description. It was a funny moment of realization.

After The Perfect Storm, you moved into war reporting—embedding with U.S. infantrymen in Afghanistan for Restrepo, walking U.S. railways with veterans in The Last Patrol and Freedom. But in many ways, The Perfect Storm seems like the beginning of those themes—a group of brothers in dangerous situations.

I hadn’t conceived of it in those terms. When I wrote The Perfect Storm, I really thought I was writing about dangerous jobs. But dangerous work is done by young men—young working-class men, typically, not that there aren’t women as well. And young men have an enormously high risk tolerance. As a result, they die in violence and accidents at something like six times the rate of young women. So, who are you going to put in a job or who’s going to be drawn to a job that has a very elevated chance of killing you?

Looking back, I realize that I’ve been drawn to writing about different forms of all-male groups. Their dynamics are fascinating. And honestly, being in those groups as a man is extremely enjoyable. When I was with a platoon in combat, I was as happy as could be. It was brutally cold and unbelievably dramatic. I mean, the helicopters and the firefights—everything was just so over the top. I couldn’t believe I was seeing Americans in a war zone. I was like, “Are you kidding? Some kid from Wichita is just returning fire in Zabul province at some Afghans. Are you kidding?”

Throughout your career, you’ve encountered a huge element of personal risk yourself—really off-the-charts personal risk. And you’ve lost friends in battle. Yet your closest call came right at home, in 2020, when your pancreatic artery burst.

I stopped war reporting after my buddy Tim Hetherington died, who I made Restrepo with. He was killed in Libya on an assignment I was supposed to be on, and at the last minute, I couldn’t go, and he got killed. After that, I stopped war reporting. I got divorced, and I remarried; I had a family. Now, not only would I not put my life at risk unnecessarily, but the aneurysm—that near-death experience—really affected me. I was very, very lucky to survive it.

The doctor was cutting my neck open to put a line into my jugular to try to get blood into me fast enough to save me. And I said, “You gotta hurry. You’re losing me right now.”

You have to know, I’m not only unmystical, I’m anti-mystical. But as that was going on—as I was dying, really—a black pit opened up underneath me, sucking me down into it. And my dead father appeared, as if to welcome me, and I wanted nothing to do with him. I mean, I was like, “I love you, Dad. But we have nothing to talk about right now.”

Then I found out that encountering dead relatives is very, very common with people who are dying. They don’t really have an explanation for it.

Whoa. And now you’re researching a book, called Pulse. Will it go into those near-death experiences or the forces that keep us alive?

I think my book is going to be looking at all of those things but from an implacably rationalist, nonsentimental viewpoint.

The experience has given me a real awareness of mortality. All we have is now. Being here right now with my children: that’s what life is for me now. I don’t regret the past, and I don’t plan for the future. I’m just, here I am, you know?