Explorers are not a dying breed. For the most part, they are very actually dead. Admiral Scott perished in the whirling drift; the dry bones of Henry Stanley, last white man to hear Livingstone’s voice, lie not in the Congo but in Pirbright, Surrey, though he’s still a long way from home.

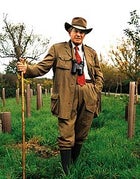

Colonel John Blashford-Snell, resplendent in Saville Row khaki, near his home in Dorset, England

Colonel John Blashford-Snell, resplendent in Saville Row khaki, near his home in Dorset, England

But a few old-school explorers are still hacking their way through the brush, square-jawed envoys to the secret world—and Colonel John Blashford-Snell is the most vividly drawn of the lot. He is quite possibly the only expeditioner who has his gear tailored on Savile Row. Or to have hauled an 800-pound grand piano 350 miles through punishing jungle deep in Guyana as a publicity stunt to raise relief aid for the flood-beleaguered Wai-Wai village.

There’s no telling his life narrowly. Blashford-Snell was born in 1936 on the Isle of Jersey; his father was an army chaplain and his mother ran a menagerie of wounded and orphaned wildlife. Raised in the faded shadow of empire, Blashford-Snell spent 37 years in the British Army as a Royal Engineer. In 1968, when Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie invited the Army to attempt the first (and rather unlikely) descent of the Blue Nile, Blashford-Snell was called to lead it. When his team’s aluminum boats proved impossible to use in African whitewater, he rigged up inflatable Avon boats with extra rubber coating, which had the advantage of bouncing off, not smashing upon, rocks. Because of this innovation, many credit Blashford-Snell with revolutionizing whitewater adventure.

After the Blue Nile voyage, the colonel and nine other “like-minded nutcases” cofounded the Dorset, England-based Scientific Exploration Society, which shepherds researchers on improbable diving-and-archaeology-and-cryptozoological expeditions into the world’s last remote climes. Blashford-Snell is forever intertwining his trips with humanitarian work—bringing eye specialists to the Dalak Islands in the Red Sea to perform cataract surgeries on the locals, setting up communication links between children in far-off lands and schoolkids in Britain.

When he’s not lost in the wilds, Blashford-Snell lives with his wife of 41 years in the unforbidding terrain of Dorset. We talked with him there one day after he’d returned from a South American expedition on the reed boat Kota Mama (devised to gauge whether ancient tribes could have traveled down the Amazon into the open sea)—and he was just about to make his first foray into the northeastern Indian state of Nagaland, which has only recently allowed foreigners across its borders.

���ϳԹ���: You’ve got quite a life story. Even the bar-bones facts are unbelievable. Where are you off to next?

Blashford-Snell: Among other things, we’ll be doing our fourth Kota Mama expedition. The first one was in 1998. We took a fleet of reed boats from Lake Titicaca to Lake Poop-. And we found a number of city sites on the way that were previously undiscovered. That was a short journey, only about 250 miles. The second time we went, in 1999, we built a much bigger reed boat and sailed from the southeast corner of Bolivia, 1,800 miles through the R’o Paraguay, the R’o P aran‡, the River Plate, and ended up in the Atlantic. Same time, of course, we did a lot of archaeology and community-aid projects—because you have to do the hearts and minds to get the people to tell you where the archaeology is. Along the route, we pulled out 1,500 teeth from the local Indians.

O: Pardon?

Blashford-Snell: They wanted it. They had incredibly bad teeth. They eat sugarcane.

O: You’re not personally traveling around yanking teeth?

Blashford-Snell: No, we had a dentist along from London. These people had never seen a dentist in their lives.

O: How did the last trip go?

Blashford-Snell: The real problem for us was that there were 300 miles of rapids on the Bolivian-Brazilian border. So we had to design a boat that was capable of going through whitewater. And, near as possible, we followed the traditional design. We produced a trimaran—three boats joined together by cables, slung very close, side by side. We got through some incredible rapids. And almost at the end of the rapids, we hit a Grade 5, or, some say, a Grade 6. It was quite extraordinary. The boat went into a hole, which was about 15 feet deep. One of the outriggers immediately tore itself away from the main hull, and we flung up in the air and capsized. All the men were thrown in the water. This boat, which by that time weighed about 20 tons, was absolutely stopped dead. And then she went down into another bad hole and rolled out of that one. Amazingly, the hull rerighted itself, rather like one of these lifeboats coming up the right way. There were still four guys clinging to the wreckage.

O: Wow.

Blashford-Snell: And there were 11 in the water at this point. They managed to swim out and were picked up by the rescuers. The boat then drifted downriver, and at this point I could see that there was no way the four men left on board could control it, so I ordered them to be taken off. We watched the boat sadly disappear into the sunset over the next lot of rapids. Next morning, I flew 20 miles downriver, and there was the boat! She was tied up at the bank, looking as if nothing much had happened to her. We rebuilt the damaged stern on the main hull, and she sailed for another 1,600 miles. That’s how resilient the reed boats are.

O: Have you always been adventurous, even as a boy?

Blashford-Snell: I was pretty sickly as a kid. I suffered from asthma, I had flat feet, I had hay fever, and I was allergic to cats. But my parents were very adventurous. My mother and father spent a lot of time galloping around the bush with Boy Scouts and Girl Guides. And they brought me up very much along those lines. Eventually my asthma disappeared, thank God. I’m still allergic to cats. But it’s very useful when there’s a tiger around. I can smell ’em a mile away. When I’ve been in the forests of Nepal, for example, usually just about the time my elephant senses it, I can smell tiger if there’s one close by.

O: You had a hellish parasite in Fiji. Is that the sickest you’ve ever been?

Blashford-Snell: I’ve had parasites—but malaria is the worst thing. I had malaria three times in Africa, and once it was nearly fatal. It’s a rather unpleasant disease. The trouble is, the drugs are also unpleasant. When I was in South America in ’99, I was on a drug that gave me hepatitis. So I had six months of that.

O: The drug gave you hepatitis?

Blashford-Snell: It’s a side effect. I went bright yellow, and couldn’t drink whiskey for six months. Terrible for me.

O: What’s the most exhilarating moment you’ve had in your travels?

Blashford-Snell: Crikey. There are so many. I suppose coming out of the Congo River in ’75, when we’d come 2,700 miles. Coming out of the river and onto the ocean, and suddenly you realized that the river wasn’t tugging and pulling at you; you were just riding up and down gently on a swell in the Atlantic. A chaplain we had with us had a service, and we stood there with the sun going down behind us. It was a service of thanksgiving on the Atlantic for the fact that we’d all lived and got through, because no one had been killed, which had been miraculous. That was certainly one of the most thrilling moments of my life.

O: Is there any obstacle that’s gotten the better of you?

Blashford-Snell: I’m not in it for pure adventure. I don’t tackle obstacles like the South Pole, the North Pole, or Everest—I don’t need to prove anything to myself. I know just about what I can do. I believe that any bloody fool can be uncomfortable. If I go on an expedition, I try to make it as pleasant and comfortable as I possibly can. I’m not averse to having a bottle of scotch carried along, and a few decent glasses to drink it from. If you asked me to climb Everest, because there was some reason to climb it, such as a rare plant on top that might help people find a cure for cancer, I think I’d build a scaffolding up the side.

O: I’d like to see you try.

Blashford-Snell: Having said that, it’s difficult when you’re trying to find lost cities or strange animals. I remember the first year we went to look for what was thought to be a mammoth in west Nepal. I didn’t really believe there was a mammoth alive—but all the local people said that there was, and that it was lumping around in this jungle. When we first got there, all I had found were these footprints, which were 22 and a half inches across. So whatever this thing was, it was enormous. The first year, we searched river valleys, brought whitewater boats down, we talked to the people, and we couldn’t find anything, except these huge footprints. The second year, I took the precaution of offering a little incentive to the local people—a week’s pay—to anyone who could actually show me the creature. And of course that worked to charm. Within days a man had come into our camp and said he knew just where this thing was, because it had just eaten his banana plantation. And we sent off a man who, as it happens, came from Marks & Spencer.

O: The UK department store.

Blashford-Snell: Yes, this guy was the manager of the big store in Belfast. And because he was the sort of guy who spent his life working out what size knickers women wore, I reckoned that he was an ideal chap to work out the size of a footprint. He went off into the jungle with this Nepalese man, and they found the footprints, and followed them. And these led into some thick jungle. So we mounted up and followed them.

We came to the outside edge of this forest. Suddenly my elephant, a dear old thing called Honey Blossom, put her ears forward, like parabolic reflectors, and she began to twitch. She could see something ahead in those trees that I couldn’t see. As we watched, I saw what I thought was a rhinoceros coming out. Then this massive dome and gigantic curved tusk stuck its head round a tree and looked at us.

Into a slight clearing in the trees came not one but two absolutely enormous bull elephants. They did look like mammoths. But they weren’t hairy. We tried to get them out into the open. And my secretary was behind me. She suggested we get all our females (our elephants were female) to trumpet, to give a few mating cries. It had no effect. And she said, “Oh, my God, we’ve got two gay elephants out there.” But we did draw them out, and we got film, and CNN showed this film all over the world. Eventually we learned they’re a type of Asian elephant. They’d been driven up into the foothills of the Himalayas by the pressure of mankind in India.

O: Do you think there’s an element in your adventuring of…well, a glimmer of madness in it all? I’m not suggesting that you’re clinically insane.

Blashford-Snell: Only those who attempt the ridiculous achieve the impossible! They say of the Royal Engineers that we’re all “mad, married, and Methodist.” I’m not Methodist, but I am married. Probably a bit mad. My great challenge has always been when someone says it can’t be done; my curiosity is sparked as to why. And that’s probably the main reason I go on these things. “You can’t get a grand piano up the Essequibo!” “Well, why not?” Basically, I’m an engineer. Having been a Royal Engineer for most of my life, everything’s always been a challenge. But I’m not like some guys who want to go walk to the North Pole on roller skates or whatever.

O: It’s hard to connect the sickly boy that you were with the person who is driven to go anywhere in the world.

Blashford-Snell: If you’re a bit seedy and you have to struggle, it makes you keener to live life to the full. What saved me was learning to dive, because my chest grew and expanded, and that helped me to get rid of the asthma. Part of the problem was that my mother had a great love of cats. She had 28 cats.

O: Your mother had a sort of menagerie.

Blashford-Snell: She had a monkey, cats, dogs, donkeys, guinea pigs, rats, you name it.

O: A monkey? Where’d that come from?

Blashford-Snell: From a regiment in Ireland. It was a South American monkey that had been a mascot. But unfortunately somebody had slammed a canteen door on its tail, which had given him a perpetual hatred of anyone in khaki! So it wasn’t really an ideal animal to have.

O: It’s a strange association for a monkey to make.

Blashford-Snell: Yeah. He was a grand chap. He was one of my great pets.

O: What was his name? Do you remember?

Blashford-Snell: Oh, with monkeys it’s always the same: Jacko.

O: Oh, right. Of course. That’s the law.

Blashford-Snell: He was funny—quite a vicious monkey. The trouble was, we couldn’t get the right food for him during the war, and his fangs grew to enormous length. And I remember, one day when I was four or five, I was teasing him.

O: You musn’t tease the monkey.

Blashford-Snell: And he bit me in the throat. Missed my jugular vein by half an inch.

O: Yikes. So, all in all, what do you think the future of exploration is?

Blashford-Snell: The battle goes on to help conservation. Sadly, as the rainforest is being destroyed, we’re losing more and more plants. It’s vital that we get the knowledge of what is there. I’ve seen the effects of herbal medicine on my colleagues who have been injured and had nothing else to use. That’s one of the reasons why I feel passionately that we shouldn’t destroy the rainforest, because we’re destroying man’s natural laboratory. I support any projects that are trying to save it. It’s a question, really, of education.