Mr. Bland’s Evil Plot to Control the World

In the dusty realm of big-league map collecting, one man cut a darker figure than his milquetoasty colleagues. Armed with an X-Acto knife and an arsenal of fake identities, he systematically ransacked the nation's libraries, hoping in his own peculiar way to dominate the globe.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The grand stack room of Baltimore’s , an elegant chamber built in 1878 and now run by Johns Hopkins University, has been aptly described as a “cathedral of books.” Rising 61 feet from its marble floor to its glass skylight, appointed in ornate cast iron and gold leaf, suffused with the smell of moldering volumes, the place indeed radiates a sense of the sacred.

On the afternoon of December 7, 1995, Jennifer Bryan, curator of manuscripts for the , was doing a little research inside the grand stack room when she started to get a bad feeling about a fellow patron. The man in question was sitting across the way from her, looking through some books that were obviously very old.

There was nothing unusual about his appearance—quite the contrary. A studious man in his midforties, wearing a blue blazer and khaki pants, he could have been mistaken for half the scholars who walk through the library’s doors. He was a withdrawn, slight-framed person with a biggish nose, smallish chin, reddish hair, and mustache.

Yet the man kept looking over his shoulder and flashing her “surreptitious” looks. Her suspicions soon deepened. “I just happened to look up and over in that direction and thought I saw him tear a page out of a book,” she remembers. “And I thought, well, now what do I do? Do I say something, or did I just imagine that?”

As time went on, the man seemed to grow flustered by her stares. Finally, he stood up and pulled open a card catalog drawer, purposely obstructing Bryan’s view. For Bryan, that was the last straw. She got up and reported him to Peabody Library officials.

A short time later, when three security officers confronted him, the man hastily gathered up his belongings and dashed out the Peabody’s front door. In a scene that might have come from some odd amalgamation of The Nutty Professor and The Fugitive, the bookworm led his pursuers through downtown Baltimore, all four of them in a jog. Crossing historic Charles Street, the procession threaded past a famous statue of Washington and around another of Lafayette. Finally, after ditching a notebook in a row of bushes, the man found himself trapped on the back steps of the .

Donald Pfouts, director of security at the Peabody Library, spoke to the man first. “I would really like to invite you back to the library,” Pfouts remembers telling him, “because I think there are some issues here that we have to deal with.”

The officers pulled the red spiral notebook—about the size of a steno pad—from the bushes and quickly discovered that Jennifer Bryan’s suspicions had been well founded. Tucked into its pages were three maps from a rare 1763 book, The General History of the Late War, by John Entick, a modest trove that the library later estimated to be worth around $2,000.

Earlier in the day, the man had presented library officials with a University of Florida ID card bearing the name James Perry, a fake. Now he told them his real identity: Gilbert Joseph Bland Jr.

An hour later, in what would turn out to be a controversial decision, the library released him after he promised to pay $700 to restore the book. Bland was in such a hurry that he forgot to take his notebook with him—and within minutes of the thief's departure, Pfouts made a startling discovery. As he looked more closely at the notebook, he realized that it was essentially a hit list containing the names and prices of rare maps as well as the names of several other major libraries at which they could be found. Then, as Peabody librarians went back through their own records, they discovered that more maps were missing from other texts that Bland had apparently handled during an earlier visit. “This guy was low,” says Pfouts. “He was violating the trust of practically every community in the country, committing crimes against our history.”

When Hopkins officials began to warn other libraries around the country about the unwelcome visitor, Pfouts’s worst fears were soon realized. James Perry had been to the University of Virginia. James Perry had been to Duke University. James Perry had been to the University of North Carolina and to Brown. At every stop, books handled by him now appeared to be missing maps and prints.

As news of the crime spread through Exlibris, an Internet site for librarians and rare book traders, Pfouts started hearing from legitimate map dealers around the country. “They’d say, ‘Look, we know this guy, and we know that he’s been doing this for a while,’”recalls Pfouts. “They didn't know how he was getting the maps, exactly, but they said he always had the rarest maps and he always had multiples of them. They could never understand why he always had everything.”

Soon the FBI would enter the case, and Bland’s name would be on the lips of nearly everyone in the world of vintage cartography, his cross-country string of heists casting a chill over this small, musty profession. Eventually, Bland would be arrested for his crimes, and after entering a series of guilty pleas, he would serve prison time while his case followed a convoluted course through federal and state jurisdictions. Late last month, Bland was set to be released from a New Jersey facility, completing an incarceration that lasted only a year-and-a-half. Though he still faces the possibility of further legal action, America’s greatest map thief will be, for the time being, a free man—a prospect that leaves curators and map collectors considerably ill at ease.

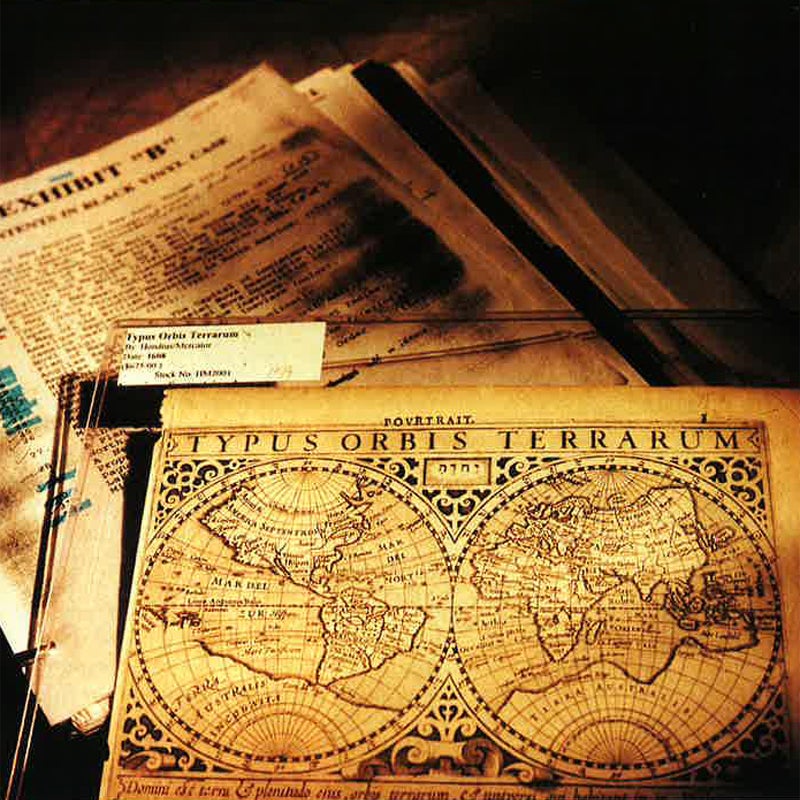

On October 31, 1995—Halloween—Gilbert Bland had an especially good day. That morning he allegedly walked into the University of Chicago’s , signed in as James Perry, and calmly sat down in the special collections room. Then he opened one of the Western world’s more extraordinary texts: a 1584 edition of Theatrum orbis terrarum, compiled and edited by Abraham Ortelius, the father of modern geography. Ortelius, a Flemish cartographer born in 1527, took up his trade at a fortuitous time, in the afterglow of the great age of discovery. Columbus had landed in the Americas, Magellan’s expedition had circumnavigated the globe, Copernicus had made his case for a sun-centered universe. Yet cartography was behind the times. Maps came in a slapdash variety of sizes and styles, many of them based on ancient Greek notions of geography—which, of course, did not take into account the possibility of a North or South America. Ortelius set out to change that, painstakingly collecting the finest maps of places throughout the known world and bringing them together in a uniform size and format. Originally published in 1570, Theatrum orbis terrarum was the first modern atlas. Ortelius put the whole world at the fingertips of the traveler—a revolution in the human imagination.

Yet now the great master's text had wound up in the hands of a kind of Anti-Ortelius, a professional scatterer of maps and destroyer of books. Bland apparently paged through the volume until he came to a cartographic gem labeled “La Florida,” the first widely available map of the broad region that is now the southeastern United States. (Ortelius added it to Theatrum orbis terrarum in the 1584 edition.)

Although the book measures 17 inches by 12 inches and its pages are so thick that they faintly rumble when turned, Bland is believed to have removed “La Florida” and two more maps from the atlas, as well as ten maps from another book. The Regenstein’s special collections room is a kind of fish tank built expressly for security; its walls are made of glass and no briefcases or pens are allowed inside. Yet Bland seems to have sneaked the 13 maps into his clothes and walked out undetected. For good measure, he also altered a librarian’s pencil-written inventory at the front of the Ortelius book, making it appear that the pages he took had been missing for years.

But that wasn’t Bland’s only alleged theft during his brief Chicago stay. Only the day before, he’d paid a visit to Northwestern University’s Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections. Curator R. Russell Maylone remembers him as “the proverbial man in a raincoat” with “a pile of books on the table spread out in a not very orderly fashion.” That day, Bland is believed to have removed six separate maps from the pages of several antique atlases, including a 1681 map of New York and three maps of the Caribbean. As Perry got up to leave, Maylone said, “I hope you found what you were looking for.”

Ultimately 18 institutions, including libraries at the University of Delaware, the University of Florida, and Washington University would report that they had been visited by a James Perry. It was an invisible crime spree, hidden amid the seldom-opened pages of centuries-old books. And now librarians, a legendarily docile people, wanted blood.

“If that man gets in front of my car,” said Northwestern's Maylone, “I’ll run over him—but in a nice way. Oh, and then I’ll back over him again.”

Gilbert Joseph Bland Jr. was something of a chameleon, a clever inventor of aliases. Over the years, law enforcement officials say, he went by the names James Morgan, Jason Pike, Jack Arnett, Richard Olinger, John David Rosche, Steven Spradling, James Bland, James Perry, Gilbert Anthony Bland, Joseph Bland. He changed careers and families without seeming to look back; when a daughter from his first marriage once asked him for a favor, she says he refused, telling her, “You're a stranger.”

People who’d met Bland would describe him only in the vaguest of terms: “clean-cut,” “quiet,” “mild-mannered,” “a shadow figure.” His face was neither young nor old. Medium height, medium weight, middle-aged, middle everything, he was a cipher—in cartographic terms, terra incognita. “The man was totally nondescript,” says Linda McCurdy, an official at Duke University’s Special Collections Library. “Part of the way he operated was to make as few ripples as possible.” Margaret Bing, a special collections curator at Florida’s Broward County Library, puts it this way: “I remember thinking the first time I met Bland, ‘Now this is a guy who fits his name.’”

Then again, the world of vintage cartography in which Bland so craftily operated is itself a decidedly staid realm. There are an estimated 10,000 antique map collectors in the United States, a punctilious subculture loosely bound together by organizations like the and the . Cartomaniacs, as these obsessive map-hounds sometimes call themselves, subscribe to periodicals such as or the more scholarly and avidly discourse on the Internet's Map History Discussion List, exchanging esoterica or trading cartographic jokes. (What did the mapmaker send his sweetheart on Valentine's Day? A dozen compass roses.) The cartomaniacs’ calendars are dotted with trade fairs where they haggle over the price of a Willem Blaeu or a William Faden the way baseball-card collectors would bargain over a Hank Aaron or a Mickey Mantle.

“Cartomania is a sickness,” says Barry Lawrence Ruderman, a dealer and self-confessed map junkie from La Jolla, California. “It's obsessive. Once you’re in up to your ankles, you want to be in up to your knees; once you’re in up to your knees, you want to be in up to your waist. I like to think that it’s sort of a beautiful sickness, because all human beings need things that stimulate them intellectually and drive them to passion. But the secondary aspect is that many of us spend insane amounts of time dedicating ourselves to map collecting. It’s a twisted pursuit. But where’s the problem in that?”

“People collect maps for a wide range of reasons,” says Edward Ripley-Duggan of the . “It's a little world over which people can have total aesthetic control. And as in any economy, whether it’s Wall Street or whatever, there’s always a rogue element. Unfortunately, certain people are sticky-fingered where desirable artifacts are concerned.”

Gilbert Bland developed his “beautiful sickness” relatively late in life, sometime in his early forties, and unlike most of the afflicted, his interest in maps seems to have had more to do with money than with an authentic passion for the discipline of cartography. In February 1994, a little less than two years before he was caught in Baltimore, Bland and his wife, Karen, opened Antique Maps & Collectibles in The Gardens, a sleepy little office and retail complex in Tamarac, Florida. Tamarac is a Fort Lauderdale exurb, a placeless sprawl of strip malls and subdivisions. It's about the last spot you'd expect to find an antique map shop—but then again, this was one antique map shop that didn't want to be found.

“Cartomania is a beautiful sickness,” says one self-confessed map addict. “Once you’re in up to your ankles, you want to be up to your knees. Once you’re up to your knees, you want to be in up to your waist. It’s obsessive.”

Though his wife was the owner of record, Gilbert Bland was apparently the guiding force behind the store, which was located just a few miles from the home the couple shared with their two children in Coral Springs. The Blands kept a decidedly low profile at the mall. “The place was basically always empty,” says one employee of a business whose windows faced Bland's shop. “We were sitting here one day thinking, ‘I wonder how he makes money?’ And then we were wondering, ‘Who would be interested in those old maps?’”

When the store opened, Bland was a complete unknown in the world of antique maps. Nonetheless, he quickly built up a moderately impressive inventory and began to cultivate a long-distance clientele. Barry Ruderman was one early client. “Bland sent out a computerized list of maps for sale,” recalls Ruderman. “It was semiprofessional looking, nothing real fancy.”

From the beginning, it was obvious that Bland was not an expert. As one inside observer later put it, “Some of the dealers were awfully wary of him—the man didn't seem to know dick about maps.” Ruderman remembers that original offering as a “bizarre mix” of materials that included a lot of worthless junk. “The other thing that was a bit odd is he really didn't know his prices all that well,” Ruderman says. “He really just wanted you to make offers. And he accepted most of the offers.”

Ruderman, a bankruptcy lawyer, says he once “sort of cross-examined Bland” about the provenance of his materials. According to Ruderman, Bland replied that he and his wife had been involved in scripophily—the collecting of old stock certificates and bonds—and had incidentally been accumulating old maps. “That was an acceptable answer,” says Ruderman, “because frankly there are two or three respected dealers who fit that general MO.” In the end, Ruderman concluded, “Gil passed the smell test.”

Bland's client base was growing. As Antique Maps & Collectibles sent out catalogs and advertised in international trade magazines, word began to spread that a little store in south Florida had an incredible supply of low- to mid-end maps. Some dealers grew a little suspicious of Bland's ability to find multiple copies of relatively scarce pieces. Others were beginning to raise eyebrows over what one dealer called Bland's “ridiculously low prices.”

But no one apparently ever directly accused him of stealing, much less demanded an investigation into his practices. “It's a very close community,” explains F. J. Manasek, a well-known Vermont dealer. “We're all friends, even though we compete in business. There's a lot of honor, which is probably why Bland could gain such easy entree.”

“The degree of trust in this business is staggering,” agrees another prominent dealer. “We literally sell tens of thousands of dollars of stuff around the world based on a phone call.”

The Blands made high-profile appearances at the two big industry conventions in 1995—the Miami International Map Fair in February and the International Map Collectors' Society Fair, in San Francisco, in October. “Bland had a major presence at both fairs,” recalls James Hess, who owns the Heritage Map Museum and Auction House in Lititz, Pennsylvania. “He was putting himself out there with the major dealers.”

Ruderman, who had dinner with Bland at the San Francisco convention, adds, “Most of all, he was interested in being a wheeler-dealer. He was looking for big buys. He was definitely crunching numbers a lot more than he was learning maps.”

“It got to the point,” recalls one respected map antiquarian, “that dealers would be saying, ‘My goodness, maps of City X have been selling rather well. Do you have any maps of City X?’ And Bland would say, ‘Let me check and I'll get back to you.’ And the very next week he’d call and say, ‘Why, yes, I just happen to have a map of City X.’”

If Gilbert Bland had dollar signs in his eyes, it's not hard to understand why. He had entered the trade during a boom time, when the fascination with ancient maps was steadily spreading from the esoteric fringes into the mainstream. Over the previous decade or so, cartomania had become something of a bull market in the United States. (The trend continues today. Money magazine, for example, devoted its March 1997 Hot Stuff column to map collecting. The headline: “These Old Maps Offer You a New Way to Double Your Money.”)

Much of the growth in antique map collecting has been fueled by one person: W. Graham Arader III, an intense and sometimes intimidating man from Middleburg, Virginia. Arader's main residence, an 86-acre estate in rolling horse country just up the road from Paul Mellon's place, is one of four that he and his wife own. Arader has made his multimillion-dollar fortune almost entirely from trading old maps and prints. “I'm the biggest map dealer of the twentieth century,” the 46-year-old Arader asserts. “There's no question about it. I sell $10 million in maps every year. I can pick up the phone and make $10,000 in a single hour. Yes, collecting has made me a very rich man.”

Before Arader entered the business in the early 1970s, old maps were mostly the province of librarians, historians, and a few tweedy collectors. Young, impudent, and by all accounts extremely savvy, Arader was determined to expand the base of investors beyond this small, druidic group. Reaching out to people with cash to burn and corporations with offices to decorate, he transformed antique maps from historical artifacts into trendy commodities.

Critics, especially rare collections librarians, have sometimes disputed Arader's cutthroat business practices, but no one would argue with his success. Luring wave after wave of new and inexperienced buyers into the market, he jacked his prices to the sky. His competitors—many of whom were appalled by his brash style—followed suit.

“It's been straight up since I started collecting in 1971, increasing 5 percent to 20 percent a year,” says Arader. Just to take one example, an edition of the ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy’s famous map book, Geographia, printed in Ulm in 1482, could be had for $85 in 1884, $5,000 in 1950, and $28,000 in 1965. Today, if you could actually find a copy for sale, it might cost you as much as $400,000.

That’s good news for Arader and his fellow map dealers but bad news for the nation's librarians, who suddenly find themselves sitting on gold mines—often without the resources to protect their riches. Predictably, a new generation of map thieves has swarmed in. In 1978, for example, Andrew P. Antippas, a professor of English at Tulane University, pleaded guilty to stealing five rare maps from Yale University. Also at Yale in the 1970s, two men disguised as priests confessed they were part of a conspiracy to steal ancient atlases and maps by sneaking them under their robes. In Britain in the mid-1980s, a man named Ian Hart sneaked a huge haul of maps and atlases out of Oxford's Bodleian Library, much of it hidden in his trousers. In 1988, Robert M. “Skeet” Willingham Jr. was convicted of stealing an enormous cache of rare books, documents, and maps from the University of Georgia, where he worked as the head of special collections.

In his usual pugnacious style, Arader lays the blame for this wave of thefts squarely on the shoulders of librarians, whom he claims are simply not vigilant enough. “Most librarians are incompetent, boring, and dull,” says Arader. “And they have this easy life. Many of them view their collections as their personal fiefdoms. But really, they don't look after their material. You know, it's not hard to tell the difference between a thief and somebody who's legitimate. If you're not intelligent enough to see these guys coming, then you shouldn't be a curator.”

Earlier in his career Arader had purchased maps that had been stolen by none other than Andrew Antippas, but nowadays the Middleburg dealer likes to portray himself as the Argus of the industry, arguing that many of his fellow dealers are less than meticulous in ascertaining the backgrounds of their inventory. “It's simple,” he says. “All you say is, ‘Where did you get this map?’ Then you listen to the story and you say, ‘Do you mind if I check your sources?’ And then if he starts waffling, you say, ‘Sir, get the hell out of my gallery!’ And if you really think he stinks, then you turn him in. In their hearts, the dealers who bought from Bland knew what was going on. If something is too good to be true, then it's too good to be true.”

At the time of his brief detention at the Peabody Library, Bland provided officials only with a temporary address in Columbia, Maryland, the town where he had lived before moving to Florida in 1994. But as news of his crimes spread, Bland fled that address and disappeared. It took the authorities more than a week to catch up with him again—time that allowed him to dispose of much of his inventory.

By the early morning of December 15, Bland had emptied his store, reportedly leaving a note for his landlord that said, “See you later.”

“I came in and a lot of the maps were gone,” says Laurie Bregman, a tenant whose shop was located just across the way from Antique Maps & Collectibles. “He’d emptied the place in a middle-of-the night kind of deal.”

Within a week and a half of Bland's vanishing, FBI agents, working with a University of Virginia cop named Thomas Durrer, tracked him down at his residence in Florida and knocked on the door, a search warrant in hand. On January 2, 1996, Bland finally turned himself in to local police.

News of his arrest came as no great surprise to many people in the industry. But others, particularly those who'd had close business dealings with Bland, maintain that they were stunned when they heard of his arrest. “My jaw dropped,” remembers Jonathan Ramsay, the owner of a map and print business in the Bahamas. “I mean, the guy was straight as an arrow. When something like this happens, you say to yourself, ‘Wow, I just don't understand human nature.’”

Ramsay heard about Bland's legal troubles when a friend from Florida faxed him a newspaper story. “I called my friend up and I said, ‘You've got to be kidding me!’ Just then, I heard a noise in the shop and I turned around and there were these three guys standing there. And I said, ‘Yes? Can I help you?’ And one of them said, ‘I'm an FBI agent.’ He'd been standing right behind me as I talked on the phone. He said, ‘Obviously, I can hear from your phone conversation that you've heard the news.’”

Another dealer who bought maps from Bland and met him face to face shared Ramsay's surprise. “Bland was the most soft-spoken and considerate guy,” he says. “It was like a contradiction. On the phone and in person, he was so quiet, and then on the other hand, the crimes he committed were incredibly nervy. I guess he was a hell of a con man.”

“It’s simple,” Arader contends. “All you say is: ‘Do you mind if I check your sources?’ and if he starts waffling, you say, ‘Sir, get out of my gallery!’ If something is too good to be true, then it's too good to be true.”

Like any good con man, Bland did not surrender without retaining a certain amount of leverage: The feds still didn't know where his inventory was stashed. Somewhere Bland had old maps of New Jersey, Virginia, and Maryland, as well as Italy, Sweden, and Norway. He had the fortifications of Montreal. He had the Missouri Territory. He had the Empire of China, the Empire of Japan, and India beyond the Ganges. He had the Eastern Hemisphere, the Western Hemisphere, and the North Pole. He even had the trade winds locked up somewhere—and he wasn't telling anyone the location. Figuratively speaking, he was holding the world hostage.

As part of his plea negotiations, Bland would agree to tell the FBI the whereabouts of the cache—a rather cunning offer that FBI agent Hank Hanburger would later describe as “a very effective bargaining chip.”

So in February 1996, Bland finally directed authorities to a storage space in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, that he had rented under an assumed name. When FBI agents looked behind its bright orange doors, they discovered an extraordinary booty, some 150 maps in all, dating from the sixteenth century to the twentieth. Taken together with the 100 or so other maps that authorities would gather from Bland's assorted clients across the country, the thief's total collection of some 250 maps would have had a market value estimated at as much as a half-million dollars. The inventory included the work of such seminal figures as Jodocus Hondius, whose seventeenth-century atlases popularized the now-standard latitude-longitude projection system of the great cartographer Gerard Mercator, and Thomas Jefferys, the eighteenth-century geographer who published one of the first important atlases devoted to North America.

FBI agents from Virginia flew down to impound the collection. Bland's “bargaining chip” had now been cashed in.

Werner Muensterberger, a New York psychoanalyst who is a nationally prominent expert on collecting and the author of Collecting: An Unruly Passion, says that the map lovers he has met tend to come from broken homes or from families that have moved around a good deal. They throw themselves into their hobby, at least in part, as a way to connect with a parent or to ground themselves in a more permanent sense of place. “Looking for maps, especially antique maps,” he says, “is really looking for the past—Where do I come from? Who were my ancestors?—and symbolically, finding security.”

Whether this profile more accurately describes Bland or the more avid collectors he preyed on, one does find certain resonances in Bland's background. Certainly his life has been a rocky one. His parents divorced when he was only three years old, and according to defense attorneys, he later suffered physical abuse at the hands of his stepfather. In June 1968 he graduated from high school in Ridgefield Park, New Jersey, a New York suburb. That same month, he had his first run-in with the law. Arrested for possession of a stolen car, he was found guilty of a lesser charge and fined $100.

A few days later, he enlisted in the army and served in Vietnam. His combat experiences would later haunt him, causing him to suffer post-traumatic stress syndrome—or so his lawyers have recently claimed. While in the service, he continued to run afoul of the law. Among other things, he was charged and briefly detained for desertion and being absent without leave.

He was discharged in 1971 and later that year married Carol Ann Talt. The couple eventually had two daughters, but fatherhood didn't seem to soften Bland's wild streak. During the early 1970s, he had a string of arrests and convictions on various charges, including marijuana possession. Then, in 1976, after separating from his wife (they eventually divorced), he found himself in serious trouble with the law. Arrested for using fake identities to defraud the government in an unemployment compensation scam, he made a plea bargain and was sent to federal prison in El Reno, Oklahoma, to serve a three-year term.

After his release from prison, Bland evidently had very little contact with his children. “He's got two children that he totally abandoned and couldn't care less about,” says Heather Bland, his 24-year-old daughter by that first marriage Nonetheless, Bland appeared to have turned his life around, at least for a few years. He married again, and he and Karen had two more children. After receiving an associate's degree from Broward Community College in Fort Lauderdale, he moved to suburban Maryland, where he worked for Allied Signal Corporation. In 1992 he and Karen opened their own computer leasing business.

It was sometime in the early 1990s that Bland became interested in maps. According to statements he made to the FBI, it happened almost by accident. “His story is that he bought a bunch of items that someone had left unclaimed at one of these U-Store-It places,” says Gray Hill, a Virginia-based FBI special agent who's worked on the case nearly from the beginning. “Included were a bunch of maps. And someone told him, 'Hey, there might be some value here.'”

The Blands moved back to Florida in 1994, opening Antique Maps & Collectibles that February. In April, they purchased (in Karen's name) a four-bedroom house in an upscale subdivision of Coral Springs for $151,400. But their financial picture was nowhere near as rosy as it appeared from the outside. Their debts were mounting fast, eventually prompting Karen Bland to declare Chapter Seven bankruptcy in late October of 1995. Court documents show that at the time of the filing — a little more than a month before Bland's brief capture in Baltimore—Karen Bland owed more than $40,000 in credit card debt alone.

Bland's lawyers would later argue that it was the failure of his computer leasing firm in Maryland that led to these financial troubles and eventually to his crime spree. But that might not have been the only factor. “I'll put another scenario in front of you,” says dealer Jonathan Ramsay. “He came over here [to the Bahamas] about four or five times—and he liked to gamble. He'd say to me, ‘I'm over here on a gambling junket.’ He would come in to see me and then he would go off to the casino.”

Whether it was to pay off gambling debts or some other reason entirely, Bland clearly needed cash fast, and he seemed to know how to get it. “He found an easy avenue to make some quick money—and he really overdid it,” says Lieutenant Detective Clay Williams of the University of North Carolina Department of Public Safety. “He got in way over his head. It became addictive. I don't think he had any conception of the federal charges that could come down on him.”

And come down they did: In a federal court in Charlottesville, Virginia, Bland was initially charged with theft of major artwork and transporting stolen goods across state lines. He agreed to plea bargains in North Carolina and Delaware state courts as well as in the federal courts. In exchange for a reduced sentence and limited immunity from further prosecution, Bland promised, among other things, to cooperate with federal authorities and to advise libraries on ways to beef up their security to prevent future thefts. In the end, Bland would be forced to pay $70,000 in restitution in the federal case (an amount he would contest to a judge, noting that the damages he'd caused were easily remediable, as the maps could simply be glued back into their original atlases), plus an as-yet-undetermined amount in the Delaware case. All told, he would serve only 17 months in various prisons ranging from Virginia to North Carolina to Delaware.

Ortelius put the whole world at the fingertips of the traveler—a revolution in the human imagination. Yet now the great master's text had wound up in the hands of a kind of anti-Ortelius, a professional scatterer of maps and destroyer of books.

Today, most people in the antique cartographic world are appalled by what they view as Bland's distressingly light sentence. “It's very easy for a prosecutor to say, 'He ripped a few pages out of a few books? I've got better things to do,'” says map dealer and lawyer Barry Ruderman. “To the 99 percent of people who don't understand the magnitude of what he's done, Bland just doesn't seem to represent a threat to society.”

However, there is still a possibility that Bland may face further legal action. Brown University's John Carter Brown Library, which is still missing two of three maps allegedly stolen by Bland, is now considering bringing a suit against him. “But the truth is,” notes library director Norman Fiering, “I would drop all the charges if he promised to come up with the missing pieces. There's an analogy to kidnappers: You're willing to let them go if they give you back your child.”

The history of cartography is full of peculiar islands. One of the manuscripts the FBI eventually recovered from Bland, for example, is eighteenth-century British cartographer Herman Moll's map of North America. It shows a continent that looks a lot like the one we now inhabit, except for one striking detail. Running the length of the west coast is a sprawling independent land mass — a famous and widely repeated cartographic fiction known as the Island of California. Many antique maps contain even weirder isles. A twelfth-century map by the Arab geographer al-Idrisi shows El Wakwak, an island said to be filled with trees whose fruit, shaped like the heads of women, continually cry out the apparently meaningless chant, “Wak-Wak.”

A good portion of the antiques stolen by Bland have themselves been consigned to a kind of island within the FBI, one that might be called the Island of Lost Maps. The lord of this peculiar domain is Gray Hill, a lanky, voluble, middle-aged special agent. Normally, Hill's job is to track down lawbreakers, but now his role has been reversed: He hunts victims. Despite an exhaustive search, the Bureau has so far been able to positively identify the owners of only about 100 of the 250 maps in Bland's collection. The rest face an uncertain exile here.

On this day, Hill is sitting beneath a photo of grim-faced J. Edgar Hoover in a conference room at the FBI office in Richmond, Virginia. On the table in front of him is a mountain of plastic bags and file folders, a zip-up art portfolio, and a U-Haul moving box. Hill is taking an inventory of his kingdom, carefully unfolding one fragile document after another, some of them printed more than four centuries ago. “I live in fear of getting these things wet,” he says, casting a suspicious glance at a can of soda sitting on the table's edge.

The maps are mesmerizingly beautiful. With the onset of copperplate printing in the sixteenth century, mapmakers had the ability to embellish their work with extraordinary detail. And in an age when art and science overlapped, the results were spectacular: Sea monsters float in the Atlantic, angels hover over the Pacific, fire-breathing horses gallop atop the the Arctic Circle. Hill pulls out a map from the 1607 edition of the famous Hondius-Mercator atlas. “This is another one that I don't have any idea where it came from,” he says.

As part of his federal plea bargain arrangement, Bland has been helping the FBI in its efforts to return the maps to their rightful owners. But even with his cooperation, the process has proven extremely difficult for Hill. For one thing, libraries don't always keep inventories of maps that are bound in books—so even if they discover one missing, they can rarely be sure when it disappeared. Moreover, most maps are unmarked. Some institutions put stamps or other identification marks on their maps, but to many librarians this practice is repugnant, the equivalent of stenciling PROPERTY OF THE LOUVRE across the Mona Lisa.

As a result, FBI experts have been forced to match each stolen map, jigsaw-puzzle style, with each damaged book, using ultraviolet light to make sure the edges line up perfectly and the paper stocks on both sides of the cut precisely match up.

Curiously, Hill sometimes finds that librarians remain in denial about thefts that have taken place under their noses, even when the evidence is incontrovertible. “I talked to one librarian who said, 'There's no way he could have stolen anything out of here.' Well, I said, 'I just know one thing. I know that Mr. Bland told me that he came to your library and stole maps.' But they won't accept it. They will not believe that they have had anything stolen.”

Or maybe they believe it all too well. As Robert Karrow, curator of maps at the Newberry Library in Chicago, points out, “A lot of library thefts have gone unreported in the past. You're embarrassed, and maybe you say to yourself, ‘What will the donors think?’ And you’re reluctant to talk about the whole issue because you don’t want to give the crazies ideas.”

On a bright, brisk day last December, in a federal courtroom just a few miles from Gray Hill's office, Gilbert Bland was scheduled to appear for a sentencing hearing, one of the many court dates that have dotted his life over the past two years. On his attorney's advice, Bland had steadfastly declined to speak with me about his case, so I'd come to Charlottesville in hopes of finally laying eyes on the man. At the appointed hour, Bland shuffled into the courtroom wearing blue prison scrubs. There were no well-wishers or family members seated in the gallery—just a few reporters quietly scribbling notes. Bland was a sunken man with a wan, jowly face. His eyes were dark and piercing. A couple of times, he leaned back and sneaked nervous glances at me, and I imagined just how Jennifer Bryan must have felt when he darted his “surreptitious” eyes at her in the Peabody Library that day: It was the look of a man who intensely dislikes to be observed.

Prison had not been good to Bland. Earlier in his incarceration, while staying at the Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail, he'd written the U.S. District judge to complain about having to live in crowded conditions with a number of violent criminals. He attempted to pass the days and months by reading, he said, but found it “impossible to concentrate” in a place where the television constantly blared, “with rap music videos, cartoons and wrestling [as] the mainstay.”

“I have tried, with the help of anti-depressant medication…to cope,” he wrote, “[but] the stress is unbearable.” Noting that two other inmates had hanged themselves since his arrival several months earlier, he said he was worried about “retain[ing] my sanity.”

In court that day, Bland's attorney argued that his troubled emotions were indeed at the heart of this case. In urging a light sentence for his client, Roanoke-based lawyer Paul R. Thomson Jr. said that Bland's map thefts were connected to his experience in Vietnam 25 years earlier. “He has a pattern of problems largely triggered by depression, a very common problem of post-traumatic stress syndrome,” said Thomson, who assured the court that his client would remain in an out-patient treatment program once he returned home to Florida.

“He recognizes that this was singularly poor judgment,” Thomson concluded.

For his own part, Bland offered no insights into the crimes, giving instead what amounted to a stock repentant-felon speech. He spoke in a meek voice that occasionally snagged with emotion. “The first thing I'd like to say, Your Honor, is that I'm truly sorry for what I've done—I'm ashamed of myself. In the year that has gone by, I've had a lot of time to think about why this happened… It will never happen again.”

Then Bland quietly slouched back to the defense table and seemed to melt into his chair, the soul of inconspicuousness.

Correspondent Miles Harvey, who regularly writes book reviews for ���ϳԹ���, wrote “The ���ϳԹ��� Canon,” which appeared in the May 1996 issue. Photographs by Chris Hartlove