A Message In Blood

There was evidence, but no investigation. A crime, but no suspects. Rumors, but no one willing to point the finger. When gunmen massacred up to 20 brown bears near a Canadian grizzly researcher's Kamchatka cabin, the warning was clear: On the lawless frontier of the New Russia, outsiders are no longer welcome.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The helicopter took off at daybreak, skirting the leaden bay before rising to thread the volcanoes surrounding the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. The old chopper, an Mi-8 with the carcass and portholes of a rusting tanker, eased out over the tundra as the peninsula narrowed, flying low as it headed toward the southernmost tip of the land. It was early in the long Kamchatkan winterÔÇöNovember 2002, according to the best guesses that came later. The season's first snows had just blanketed the valleys slanting off the volcanoes, and the white earth below was barren except for the stone birches, their fat branches twisting skyward.

Packed in close, the men sat stiffly as the chopper bobbed south, covering the 135-mile stretch to their wilderness destination in roughly two hours. Drowned out by the roar of the blades, they said little. Each held tightly to his weapon until, below them, there appeared a small, pristine lake, filled with some of the biggest salmon in the world. As they touched down beside a cabin, the men crunched into the hard snow.

They probably had little trouble accomplishing their mission. After all, the bears of Kambalnoye had lived in close quarters with two North American researchers for seven years. They'd almost always tolerated visitors. One or two, expecting a familiar face, may have even run up to greet their killers.

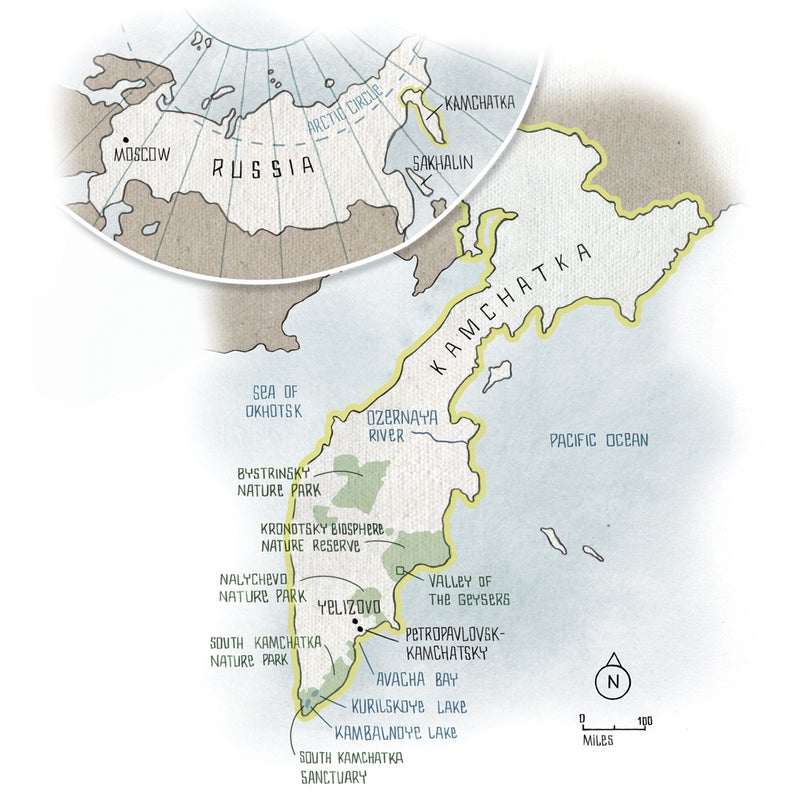

That's how wildlife researcher Charlie Russell imagined it, anyway. But all he really knew was this: In a well-orchestrated operation that amounted to mass murder in the wild, as many as 20 Kamchatkan brown bears or grizzlies, as the species Ursus arctos is known in North America┬Śwere shot in the area around his cabin on Kambalnoye Lake, in the 500,000-acre South Kamchatka Sanctuary, a state-run preserve that is home to the densest population of brown bears on the planet. Among the victims were several subjects of his groundbreaking and controversial research, a group of bears that had been studied as closely as the Rwandan mountain gorillas made famous by the late Dian Fossey.

Russell, now 63, discovered the massacre in May 2003. He returned to the lake, as he did every spring after spending the winter back home, north of Calgary, Alberta, to find one of the cabin windows pried open. Inside, hanging on the wall, was a small sack of lifeless, twisted flesh, as dark as burnt coffee. It was the gall bladder of an adult grizzly.

“At first I couldn't even look at it,” Russell recalled. “I tried to pretend it wasn't there, that it wasn't real, that it couldn't be what I knew it had to be.”

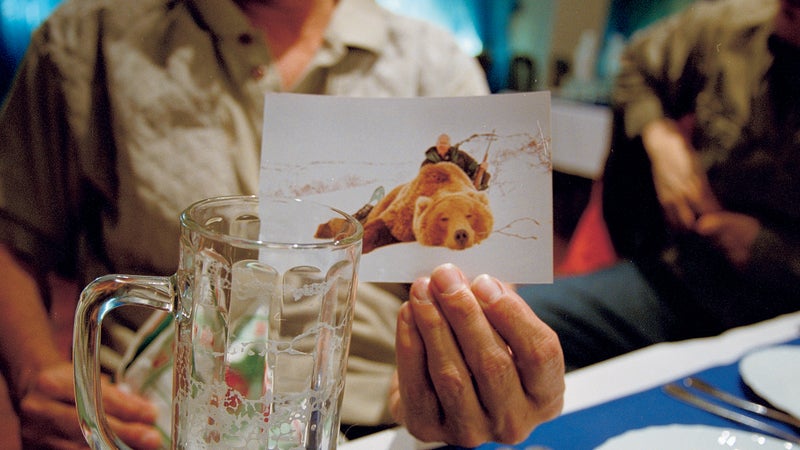

Dried and sold as an aphrodisiac and cure-all in Asia, Russia, and North America, bear gall has long been treasure for poachers. At the height of the black market, a few years back, 100 grams could fetch $3,000. (A dried gall bladder weighs roughly 60 grams.) But by 2003 the market was glutted, and the price had fallen to a dollar or two a gram. To Russell, the economics did not add up; the slaughter didn't seem worth the poachers' efforts.

Other than a few bits of hide and hair in the snow, there were no signs. Then, slowly, clues began to surface: Two garbage bags full of empty food tins turned up hidden in the pines behind the cabin, then a bag of spent shotgun shells, which had been loaded with lead slugs. Finally, as the snow melted, heavy boot prints emerged, stamped into the previous season's first snowfall. Over the course of a few days, Russell surmised, a small group of men had used the cabin as a base. The bears had probably been easy to pick off as they made their last prehibernation fishing forays down to the lake.

Russell felt excruciating responsibility for the bears' demise. A filmmaker, rancher, and self-taught grizzly expert, he had first come to Kamchatka in 1994, with his personal and professional partner, Canadian artist and wildlife photographer Maureen Enns. They shared an audacious idea: Both believed that grizzlies were not innately dangerous and unpredictable; it was our fear, not their aggression, that was the problem. They set out to live among bears but, in time, ended up going further: The couple decided to raise three grizzly cubs in the wild┬Ścubs that had been orphaned by poachers. They would teach them to live on their own, proving that bears could form long-term, trusting bonds with people.

From the start, Russell's plan stirred debate among bear experts. He was not a biologistÔÇöhe gained his years of experience with grizzlies by shooting wildlife films in CanadaÔÇöand to scientists, his methods had always seemed naive. They admired Russell's innate ease with bears, but many called him dangerous.

“He's not highly respected, even if he is liked,” said Charles Jonkel, 74, a biologist who runs Missoula, Montana's , a nonprofit dedicated to preserving bear habitat. “What Charlie does is not science. He knows that. It's got value, though. Over the years he's taught even the most diehard so-called experts to take another look at how we think about bears.”

While a few North American programs aim to reintroduce black bears to the wild, no one has tried to do it with grizzlies. “It's problematic from a number of points,” said Larry Aumiller, 60, director of Alaska's , home to the state's largest concentration of grizzlies. “First, how do you get the cubs? How do you raise them? These things are all fraught with problems. Then there's the question of why you would spend the energy and money on only three or four bears when you could focus those resources on a much wider population.”

Russell didn't just take on the scientists. Over the years, as he became dismayed by rampant poaching in the South Kamchatka Sanctuary, his idealism evolved into activism. Stymied by official channels, he'd recruited and financed a small, well-armed force of rangers at the sanctuary's Kurilskoye Lake, a prodigious breeding ground for wild salmon┬Śand thus a very attractive spot to bears. What had started as a personal experiment became a civic crusade, and it was this turn that likely led to the bears' deaths. Russell knew the rules of Kamchatka. He knew how corrupt its officials were, how venal the bosses who controlled its hunting territories and how lethal their union could be for his bears.

“Our bears were murdered in cold blood,” Russell said, home in Alberta for the bleak winter of 2003┬ľ04. There was no drama in his voice┬Śjust sadness, infinite and lonely. He knew how the grizzlies had been killed. It was the why that ruined his sleep. “The usual scientific question,” Russell said, “the hit that we fed the bears and therefore raised them to be killed┬ŚÔÇöthat's one I won't accept. But were we naive about the way things work over there? You bet we were.”

In the months following the discovery of the massacre, the crime remained shrouded in mystery. There wasn't even an official investigation. Names were whispered, of bosses angered by Russell's success, including the man who controlled nearly everything on Kamchatka. His name was uttered without introduction, like Bush or Putin: Kovalenkov. But there was no evidence. And in a region suffering from an interminable Soviet hangover, the deaths of a few bears didn't rank high on anyone's list of woes.

Half a world away, Russell was reeling from other blows. In October 2003, his friend Timothy Treadwell, 46, a controversial bear watcher from California who filmed the animals at close range, and Treadwell's girlfriend, Amie Huguenard, 37, were killed by a grizzly in Alaska's Katmai National Park. In December, another colleague, 60-year-old Vitaly Nikolaenko, a Russian photographer who'd lived among the bears of Kamchatka's giant since 1968, was killed by a rogue male.

Russell and Nikolaenko had been respectful rivals. He was closer to Treadwell, whom he and others had often warned about being too reckless among grizzlies. Treadwell, for example, refused to use pepper spray against aggressive males, a risk Russell deemed suicidal. “Charlie's out there,” said Aumiller, “but he's not exactly in the Tim Treadwell tradition.” Both men pushed the limits of human-bear contact, but Russell had always taken precautions electric fences circling camp, pepper spray as a last resort┬Śaround problem bears.

Russell didn't like to think of himself as a sole survivor, pressing on, but he couldn't let go. So in May 2004, just as the Kamchatka bears were emerging from their dens, he decided to go back. He didn't expect to unravel the mystery. His aim was more modest: to pick up the pieces, to find some way to start again.

Enns, however, would not accompany him. “After our bears were killed, that was it,” Russell said. She wanted no more of Kamchatka, and she decided to end her relationship with Russell as well. “My work on Kamchatkan bears continues,” Enns said. “I'm doing a book about what I learned there. But I don't feel ready to go back.”

“She needed to move on,” Russell would tell friends in Kamchatka. “And I cannot. I cannot give up on this place, these bears. I will not give in, no matter what happens.”

When Russell and Enns first scouted Kamchatka, the region had only recently been opened to foreigners, after decades of Soviet lockdown. To them it was an Eden, unspoiled bear country where they could make their own rules. And, of course, finding bears would not be a problem: In Kamchatka, some 10,000 grizzlies roam an area one-sixth as big as the territory inhabited by 30,000 bears in Alaska.

Nearly the size of California, the 1,000-mile-long peninsula was stocked with ICBMs, MiGs, and nuclear submarines, the first line of defense on the Soviets' eastern front during the Cold War. Since Kamchatka was off-limits to most Soviets, its wildlife was protected by default. But after the fall of the Soviet Union, in 1991, the region was again opened to the West and the newly moneyed Moscow elite. With this, Kamchatka's vast natural resources suddenly faced 21st-century threats, even as its residents struggled to develop a modern economy.

Today, some of what's happening is low-impact tourismÔÇö500 Western fishermen fly in every summer to catch and release salmon; snowboarders and heli-skiers make fresh tracks on Kamchatka's volcanoes; and thousands of tourists helicopter to the famed Valley of the Geysers, the region's Yellowstone. But tourism is just gaining a foothold. The real growth industry has been bear hunting often poorly managed or illegal along with poaching of everything from salmon to snow sheep to lynx.

ÔÇťWere we naive about the way things work over here? You bet we were,ÔÇŁ Russell said. ÔÇťBut the usual scientific question, the hit that we fed the bears and raised them to be killedÔÇöthatÔÇÖs one I wonÔÇÖt accept.ÔÇŁ

When conservation funds dried up after the Soviet collapse, Kamchatka's Kronotsky Biosphere Nature Reserve the 2.4-million-acre centerpiece of Kamchatka's five protected areas and the agency that administers them was only too happy to host Russell and Enns. The couple's dollars doubtless helped warm the relationship. In a decade, Russell said, they spent more than $1 million on their bear project, raised almost entirely through small grants from Canadian and American foundations and individuals.

In time, the reserve's officials granted the couple known to locals as nashi Kanadtsy, “our Canadians” extraordinary autonomy. In 1996, they built a birch cabin on Kambalnoye Lake. The next spring, they learned that three female cubs orphaned by poachers had turned up at the zoo in the town of Yelizovo. With a discreet nod from the zookeeper, the Canadians “stole” the cubs, as Russell put it, and took them down to the lake by helicopter, convincing the reserve to legalize the “adoption” after the fact. They named the cubs Chico, Rosie, and Biscuit and started training them to someday reenter the wild.

For six seasons at Kambalnoye, from 1997 to 2002, Russell and Enns worked with the cubs as they grew into 500-pound grizzlies. They taught them to fish, kept predator males away with an electric fence, and showed them new territory by leading them in kayaks across the lake, Enns paddling as the bears swam behind. Even as independent adults, the three stayed uncommonly sociable. Every spring, after the annual return to Kambalnoye, Russell and Chico would rub noses, and he would place his palms on hers, knitting his long fingers through her claws. The biggest surprise was that wild bears befriended the couple as well. One female, nicknamed Brandy, even took to leaving her young with them to baby-sit.

By the fall of 2002, the project was nearing completion. Rosie went missing in 1999 killed, the couple believed, by a predator male. Chico took off on her own in 2000. Only Biscuit remained. Meanwhile, Russell and Enns had gained international fame; they were covered in television documentaries and in newspapers around the world. Their 2002 chronicle was a bestseller in Canada, and the lushly photographed adaptation would soon be published as in the U.S.

Most important, they believed Biscuit had bred; if all went well, she would nurse her first cubs in the spring of 2003. Reintroducing bears was remarkable enough; having one breed and successfully raise a new, wild generation was astounding.

“That would have certainly been a landmark,” said Natural Resources Defense Council bear scientist Louisa Willcox, an ally and supporter of Russell's. “Something few could dispute.”

But Russell never saw Biscuit again. He feels certain she was killed.

Nine time zones and 4,000 miles east of Moscow, Kamchatka's sole city of Petropavlovsk-KamchatskyÔÇöknown to foreigners as P.K.ÔÇösits above one of the world's most alluring harbors, Avacha Bay. Winters here can last ten months, but when the icy sea fog lifts, a picturesque port rimmed by volcanoes emerges.

I joined Russell on his difficult return trip in 2004. We met in May, when the spring thaw had already lured the first Westerners: heli-skiers taking advantage of the last snows and American hunters streaming in from the backcountry in mud-caked jeans, carrying long rifle cases and duffels heavy with skins.

At first glance, Russell looks better-suited for retirement than for animal wars; his unruly curls long ago turned silver, and he moves in an easy shamble. Mindful of his blood pressure he has had surgery on his aorta he tries to stay away from sweets and stress. But his face is craggy from years in the wild, and his large hands are like paws. You can't spend much time with him without being awed by both his ease in the natural world and his willpower.

The Yelizovo Zoo, naturally, distressed him. Tucked away in a grim Soviet-era outpost half an hour northwest of P.K., it could easily have been mistaken for a roadside animal market. Two new cubs had come in orphaned, like Russell's, by poachers. Anatoly Shevlyagin, the stout director who had given Russell his first three bears, knew the cubs could drum up business, but it would be hard to keep them. I'd seen him on the local news asking for donations of food. Now the zoo was swimming with parents and toddlers, all carrying candy and tins of sweetened condensed milk. The sight of so much sugar headed for a species accustomed to salmon and berries made Russell pale.

Though he's spent a decade navigating Kamchatkan officialdom, Russell speaks only two words of Russian comprehensibly da and nyet. He asked me to translate as, shyly, he gave Shevlyagin a wad of rubles to help support the cubs. The zookeeper thanked Russell warmly. But he warned that the money wouldn't go to the cubs. He had to buy a new pump for the zoo's tiny pond. The water had become fetid, he explained, and he'd lost two crocodiles in as many years.

Across town, in the cinder-block headquarters of the Kronotsky Reserve, it was so cold that the staff wore down jackets. To some in Kamchatka, I was starting to see, Russell was a source of amusement or, worse, a thorn in biologists' sides. Vladimir Mosolov, the head of Kronotsky's scientific department, was candid about this. “Our Canadians dreamed of becoming famous like those Brits in Africa with their lions,” he said, alluding to , George and Joy Adamson's 1960 tale of returning the lioness Elsa to the Kenyan grasslands. But any talk of ascribing emotions to predators made his face contort. “This isn't Africa,” he huffed. “We have our own scientists and our own ideas about science.”

As for the massacre, the reserve had taken a hard line, refusing to believe that any bears had been poached. “Twenty bears familiar to me,” Mosolov said, mocking Russell's claim about the number killed. “What does it mean, 'familiar to me'? It's nonsense. Absolute nonsense.”

I heard more of the same when I phoned the regional prosecutor, Aleksander Voitovich, to ask about the investigation. “What investigation?” he barked. I mentioned that, in November 2003, the Los Angeles Times had reported that Voitovich was “investigating the case as a poaching.” Apparently not. “There is no case, because there is no proof these bears were killed,” he said. How was that? No carcasses had been found. With no carcasses there was no case, and with no case there could be no investigation. With this circular logic, he called the matter closed.

In the decade since the Soviet collapse, no region of Russia has fallen further or faster than Kamchatka. There are projects to mine gold and nickel, and a natural-gas pipeline has been haltingly under construction, but it has failed to lure the multi-billion-dollar petroleum deals of its neighbor, Sakhalin, across the Sea of Okhotsk. An economic up swing is still nowhere in sight. A big question, as always, is whether development and wildlife can coexist.

“Kamchatka is a test case,” said Guido Rahr, 43, president of the Portland, Oregon-based , a conservation outfit funded by such top U.S. philanthropists as Intel cofounder Gordon Moore. “It's one of the last great chances we have anywhere to save incredible natural bounty in the face of inevitable economic development.”

“But it's still a little wild over there,” Rahr added. He didn't mean the bears.

Poaching is a huge problem┬Śillegal salmon caviar, for example, is helicoptered out by the ton. But the big money on Kamchatka comes from the spring trophy hunt, a legal, state-sanctioned harvest in which Westerners pay as much as $12,000 for a chance to shoot a giant grizzly. The spring hunt would raise an outcry in North America: Dark bears make slow and easy targets against the white snow, and though no one hunts from helicopters anymore, guides are still used to flush animals toward clients, who have snowmobiled in.

Everywhere in the dark copses there were bears. We counted nearly 50. Some 10,000 grizzlies roam the Kamchatka Peninsula, an area one-sixth as big as the territory inhabited by AlaskaÔÇÖs 30,000 bears.

“In Alaska, you can only get a bear tag once every four years,” said Denny Geurink, a Michigan outfitter who has brought more than a thousand Americans to Kamchatka since 1991. “In Kamchatka, I can get you two a year.”

Kamchatka's bears, moreover, are generally larger than American grizzlies; females can top 700 pounds, males as much as 1,400. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service inspectors in Anchorage, who greet the weekly flights from P.K., recorded 148 bears coming back through Alaska in spring 2003. Of the 108 hunters who traveled through Anchorage, only six had not gotten a bearÔÇöa 94.5 percent success rate. “For bears,” said Bruce Woods, Fish and Wildlife's Anchorage spokesman, “that's pretty astounding.”

This rate of culling cannot be sustained, especially when by all estimates there are even more bears poached each year. No one knows the exact size of Kamchatka's bear population, but local wildlife biologists estimate that 10,000 live across the entire peninsula. Kamchatka's Hunting Regulation Department sets the annual kill quota at 500 to 550, but that's just the legal take. Multiply that two or three times, said Igor Revenko, a ranger and biologist who worked with Russell and Enns in the South Kamchatka Sanctuary, and you'll get the number of illegally poached bears. Russians pay less for a bear tag, but the price hike from $21 to $214 in 2004 is too rich for most Kamchatkans. Even formerly law-abiding Russians take bears without a permit, and there's little enforcement.

“Every man in Kamchatka can hunt for bear illegally,” Yuri Garashchenko, head of the regional natural resources department, told me. “And most do.”

At the current rate, scientists like the late Vitaly Nikolaenko, the researcher killed in 2003, fear the population cannot survive. For years, Nikolaenko was the lonely champion of a ban of the spring hunt, a practice that he and others believed devastates the gene pool, as hunters pick off the population's biggest males, the brazen ones that emerge from hibernation first.

There have, however, been recent signs of hope. The great mass of Russians, all too aware of the Soviet ecocide that decimated their land, have a passionate sense of the need to protect their environment. And though funding remains almost nil for state-run environmental operations, international groups have taken up some slack: The United Nations Development Program is providing $13 million for Kamchatkan ecotourism and biodiversity projects and $14 million for salmon conservation; and the Wildlife Conservation Society, the scientific arm of the Bronx Zoo, is conducting the first thorough study of the region's bear population.

More encouraging was the shocking move that came last July, when Kamchatka's governor, Mikhail MashkovtsevÔÇöafter a much-publicized state visit from President Vladimir PutinÔÇösuddenly reversed course and banned the spring hunt, beginning in 2005. All 500 or so tags would now be issued for the fall hunt, when far fewer Westerners brave the conditions and bears are harder to find.

In Moscow, I'd heard how Kamchatka had become a political problem for Putin. “The president is aware of the mess,” said Yulia Latynina, a commentator for The Moscow Times, “and he is determined to clean house.” Some said it was a hollow political move, a shill by Putin to gain badly needed good press in the West. But rarely does Putin brook untidy disarray in any Russian region. If Kamchatka had made it onto the Kremlin radar, you could be sure there would be a serious push for change.

“Charlie got in many people's way,” the old hunter was telling me. “But most of all Kovalenkov's.”

Roman, whose name I've changed, was driving us out of P.K. in his battered truck, a thirdhand Japanese import, like all cars in Kamchatka. We barreled along, past wooden shacks slanting in on themselves, ruins of fishing villages that dated from the days of the czars. The cratered highway seemed nearly as old.

Roman advanced a theory that I'd first heard in the headquarters of the Kronotsky Reserve, where a veteran scientist, one of Russell's staunchest opponents, had pulled me aside. “Forget the poachers,” he said. “There's one power on this peninsula.”

By all accounts a man of charm and ingenuity, businessman Anatoly Grigorievich Kovalenkov seemed to embody the best and worst of Russia's post-Communist evolution. Back in Soviet days, Kovalenkov had sat atop the regional gospromkhoz, the “state hunting enterprise” controlling the harvest of Kamchatka's game, fish, and fur. When the Soviet Union fell, the first spoils went, naturally, to those in the closest reach┬Śand those with the firmest grip. Kovalenkov was no mobster, no bandit, but he'd succeeded in building an empire out of Soviet ashes when no one else could.

With only a handful of helicopters available on Kamchatka for taking out hunters and ecotourists alike, Kovalenkov's company, KrechetÔÇö”Gyrfalcon” in RussianÔÇöhad for years enjoyed an unyielding monopoly on the tourism trade, turf that Kovalenkov, sources said, protected ruthlessly with help from a private corps of the peninsula's best guides, running it as a de facto preserve for his own hunting, fishing, and ecotourism clientele.

“Krechet has enjoyed a certain exclusivity,” said Armen Grigorian, of the Biodiversity Conservation Center, Russia's largest environmental organization. Grigorian spent months last year writing a management plan for Kamchatka's protected areas. With considerable dexterity, he explained the tangled relationship between Krechet and the Kronotsky Reserve. “In the 1990s, all the reserves in Russia faced the same terrible problem: no money. Not for science, not for protection, and certainly not for any kind of ecotourism infrastructure.” Kronotsky got into ecotourism for one reason: poverty. Tourism filled the reserve's budget. But much of the money, Grigorian said, “went to the side, under the table and into the pockets of local businessmen.”

For his part, Russell at first thought he could work with Kovalenkov. After all, the chopper that ferried Chico, Rosie, and Biscuit to Kambalnoye had been provided by Krechet. For all his charisma, however, Enns had sensed that Kovalenkov was a “two-edged sword.” Over the years, the Canadians' relations with the boss would sour, though it began with promise.

“When you came up with a new idea, an interesting project,” Enns said, “he would say, 'By all means, you can come under my roof. I'll protect you.' ” She had used the right wordÔÇöKovalenkov is what's known in Russian as a krysha, a roof. Every city, town, and village in Russia has at least one krysha: a power broker who is both arbiter and protector.

Nothing, and no one, on Kamchatka is black-and-white. Conservationists are also hunting guides, and local bosses are among the community's most generous benefactors. Kovalenkov, in addition to his diverse business holdings, was known for his civic ventures, funding scientific research, aiding the region's decimated native peoples, and, at one point, launching a local television station.

“He was going to be at the head of every venture,” said Igor Revenko, the former sanctuary biologist. “If you get him involved from the very beginning, he likes that. But try to do something on your own or with someone elseÔÇöwatch out.”

In the mid-1990s, Krechet won a decree from the regional government for a long-term claim┬Śsome say for ten years, others up to 40┬Śto the air rights from P.K. to the Valley of the Geysers, the most popular ecotourism attraction inside the Kronotsky Reserve. Nikolaenko had built a cabin in the scenic valley in the 1970s. One day in 1996, it burned down. The ground did not remain bare for long. A new hotel was built. Kovalenkov's company ran it.

No one has formally accused Kovalenkov of anythingÔÇönor are they likely toÔÇöbut Roman, who worked for him for more than a decade, felt sure he would have no qualms about being involved in the bear massacre if it suited his interests.

In the boss's employ, on too many hunting trips to count, Roman said, he'd done what he was told to do: He'd rousted bears from their dens, herded them down mountains toward hunkered-down American hunters, cut open their fresh carcasses, and dug deep to pull out their gall. But one day he decided he'd had enough. “Ever since I quit hunting,” he told me, “I can sleep.”

Roman is a big man, deaf in his gun-side ear like many lifelong hunters, and his hands are covered in calluses. He wore all black old jeans and a leather coat creased with wear. As for why Kovalenkov might go after Russell, he said that was simple: “Charlie flew. That was his offense. He could see.”

Early in his Kamchatka adventure, Russell had brought over from Canada a Kolb ultralight, a small aircraft powered by a 65-horsepower engine and built by Russell himself. The Kolb was his magic carpet; flying low over the sanctuary, he started to see snowmobile tracks and other poaching evidence that no one else could. One September afternoon in 1997, from a thousand feet up, Russell and Igor Revenko spotted a Soviet military ATV churning up a hillside deep inside the sanctuary. Russell swooped lower, bringing the Kolb in close. Inside the ATV, he'd later learn, were freshly poached snow sheep and brown bears.

Maybe it wasn't the smartest move to buzz a posse of well-armed Russian hunters deep inside a protected area. But the bet paid off. Revenko captured the scene on video and presented it to prosecutors in P.K. It turned out one of the passengers was Valery Golovin, the director of the sanctuary himself. To everyone's surprise, prosecutors brought criminal charges in the winter of 1997.

In court, Golovin played dumb. “I can't imagine how all this happened,” he told the judge. “I blacked out.” Golovin was fined 56 billion rublesÔÇö$9.3 million, a sum so outlandish as to be unpayableÔÇöand allowed to disappear quietly. His boss, Sergei Alekseev, the director of the Kronotsky Reserve, lost his job. (He landed on his feet; he now runs his own hunting trips.)

Emboldened, Russell had gone further. “I couldn't believe what was going on around Kamchatka,” he told me. “It was just poaching everywhereÔÇöfor caviar, for salmon, for bears. And if there's no fish, there are no bears. It's all one circle. That's why I realized we had to go after the poachers, of all kinds, no matter their prey. The reserve wasn't doing it. They couldn't. Just didn't have the money or the means, even if they had the will, which only some of them did.”

Cobbling together more small grants, Russell gave the reserve money to pay four rangers and build a cabin for them at Kurilskoye Lake. In 2000, when the reserve's crew proved inept, he brought in two Russian special forces officers who had come home from the bloodbath in Chechnya. The men loved their summer in the bush, and they did their job well. They not only found caviar poachers; they arrested them.

In P.K., the news made headlines. But to Enns, in retrospect, it was probably the last straw. “When Charlie took on the caviar poaching,” she said, “that's when the tide turned.” The tax police and the FSB, the secret police who are the heirs to the KGB, went after Russell for flying an unregistered aircraft in the sanctuary: a border zone, they claimed, with military significance. The local tabloids were more direct: They called him a spy. The battles in local government and in the papers dragged on for years, but in 2003 the reserve took possession of the ultralight.

Roman said the saga made his stomach turn. He spoke in a torrent, his words tumbling out and his foot leaned on the gas. His was a canto of loss, regrets piled up over a lifetime. He had a grudge against his old boss, no question about it. But he also had a conscience to clear.

Whoever killed RussellÔÇÖs bears was not out poaching gall, Pavel believed. YouÔÇÖd need a lot of men and a helicopter to hide the evidence, but it could have been done: ÔÇťjust cut the skins clean, drag the carcasses in the chopper, and dump ÔÇÖem in the lake.ÔÇŁ

Did he have any evidence Kovalenkov was involved? Only circumstantial. He said he heard Kovalenkov's guides┬Śhis old colleagues┬Śon the field radio in the days after the killing. The Canadians, they'd said, had gotten what they deserved. Roman knew that, given the way things on Kamchatka worked, the proof would likely never come to light. But to him the economics were damning enough. No small-time poacher would rent a helicopter at $1,200 an hour to kill 20 bears. No, he said, “this wasn't about the gall.”

That week last May, I got a chance to run Roman's theory by a poacher, whom, for his own protection, I'll call Pavel. Pavel made no effort to hide that he hunted illegally; for him it was a means of survival. He put the lie to the line, often repeated across Russia, that big-time poachers were the problem. A heavyset former border guard on the cusp of 50, he'd come home after the Soviet fall, like many military men, to find himself out of work. There was a wife and son up north, and a grown daughter on the mainland. He lived in a two-room apartment on the far side of Avacha Bay, with two stuffed bears for company. “Sometimes,” he said as he showed me around, “it gets lonely, just the three of us.”

Pavel agreed with Roman that no one would fly all the way to Kambalnoye Lake for the gall. “Can't sell the stuff anymore,” he said, slicing me a sliver of dried gall he had on hand. He opened his fridge wide, and visions of Jeffrey Dahmer surfaced. First he pulled out a massive, skinned bear paw, frozen white and nearly as long as his forearm. Then a tall jar.

“Pure fat,” he said, swigging the dark liquid. “Best cure for a bad stomach.”

Whoever killed the bears put in too much effort to be merely poaching, Pavel believed. You'd need a lot of men to hide all that evidence. But it could have been done. “Just cut the skins clean,” he said, “drag the carcasses in the chopper, and dump 'em in the lake.”

With the guts cut out, the remains would sink like stones.

For more than a week last spring, the dismal Hotel Petropavlovsk had become home. Each day, in the gloom of its barren lobby, Kamchatka's strange mix of foreignersÔÇöthe snowboarders, the heli-skiers, and the huntersÔÇögathered to wait for “weather,” as the Russians call skies clear enough to fly. While we waited to get permission to visit Russell's ranger station down at Kurilskoye Lake, I spent the days cautiously talking to the locals, while Russell fumbled around town trying to get his plane back from the reserve.

Finally, one morning, the smokestacks in P.K. belched straight up. We decided to forget about getting permission and recruited Viktor Podakysonov, a burly helicopter pilot famed among the cognoscenti as Kamchatka's ace. Viktor, who'd known Russell for years, cut us a bargain rate.

Viktor's ride was a tiny, 18-year-old Soviet Mi-2 helicopter. He lifted the rust bucket up high; almost immediately the solitary huts and swirling snowmobile trails receded and Kamchatka's geography took center stage. Each window of the Mi-2 revealed the range of the possible: jagged peaks and sudden valleys, veined with rivers and crowned by volcanic lakes the color of gemstones. When a skylight of blue opened before us, you could see beyond the volcanoes to an immaculate coastline. The tundra turned pure white, a desert of plush, untouched snow.

Russell looked sideways at me, shaking his head. “Never seen it so deep!” he screamed above the chopper's roar. The snows would mean that we couldn't walk along the lake, close to the bears. But Russell was delighted. Most poachers, he knew, used snowmobiles and couldn't reach the sanctuary.

All the way south, Russell scanned the cliffs and valleys. On occasion, his eyes would come alive. “Skid marks!” he'd yell, pointing to ridges where newly risen bears had come out to play. But now, as Viktor swooped low across the lake, just 50 feet above its silvery sheen, we saw one: a dark mass lumbering alone on the rocks at the water's edge. Our first live Kamchatka brown bear, massive and contented, was peering up at the steel bird in the sky.

Viktor set down near the forlorn little ranger post, a ramshackle assemblage of logs, smoke, and half-starved dogs a hundred yards from the lake. The four rangers, a scruffy lot who did not inspire confidence, scrambled to fetch us on snowmobiles. These were the best the reserve could offerÔÇöthe special forces vets were goneÔÇöand Russell was already disgusted with them. The previous winter, after a band of caviar poachers had been discovered operating unchecked in the sanctuary, he had stopped paying them.

Inside, the cabin air was heavy with the stench of Russian tobacco and lonely men. Brown bread and ramen noodles crowded the table. The rangers sat drinking vodka-laced tea, which they offered to our pilot. The head ranger, Timofei Dokhno, wore a silver Russian cross around his neck and blue tattoos on his arms. “These bears are our national treasure,” he said, asking me to translate for Russell. “If we don't protect them, we'll lose the entire ecosystem.” These men, he said, were “the last line of defense.”

Russell didn't want to hear it. Timofei, he growled to me, was the reason he had stopped paying the men in the first place.

The snow was too deep to hike, so we again took to the sky. Suddenly, not in minutes but in seconds, bears were everywhere, the dark centerpieces of the white landscape. First one boulder came to life, then another. As we circled up high over the woods, the windscreen filled with a gorgeous female clambering up the ridge. Two cubs scampered behind, struggling in the snow. Russell yelled at Viktor to fly higher.

Viktor lifted up fast, executing a 270-degree turn back over the lake. Everywhere in the dark copses I saw bears. Russell and I counted nearly 50. “Too many,” Russell yelled, “to keep track.”

Russell was smiling wide for the first time in two weeks. I thought of his odd place in this remote world. His eyes glued to the glass, his face seemed almost beatific. He hadn't slept much for days. He'd been seized by a new ideaÔÇöa vaguely articulated dream to start a foundation that could give the bears a safe future. He only needed the money. Half a million dollars a year, he reckoned, could lock up the whole reserve. Russell already had a plan to start over: He would turn his old cabin into a permanent rehabilitation facility. He would raise the cubs we'd seen at the zoo.

To an outsider, the scheme may have seemed delusional, but sitting in the deafening Mi-2, it felt entirely within reach. I looked hard and saw Russell for the first time. Here was a self-made naturalist, all alone in his 64th year, but more determined than ever to save a slice of the world's remaining wilderness. Not, truth be told, so that humans could delight in its wonders but to ensure the survival of his truest friend on earth.

Back in P.K., Russell landed hard. He knew that, unlike the international conservation groups, he didn't have the clout to get funding from the UN's Development Program. So he said to hell with that. To save Kamchatka's bears, he now was convinced, the program would have to be homegrown and Russian-run.

In fact, in the months he'd been gone, a new order had quietly emerged, one in which he'd have more of a chance. All winter, the locals joked, Kovalenkov had been in hibernation. There'd been an accident: In August 2003, an Mi-8 headed for the Kuril Islands, southwest of Kamchatka, came into heavy fog and crashed. On board was a VIP delegation led by Igor Farkhutdinov, the governor of Sakhalin. All 20 aboard were killed. Pending the inquiry, both Krechet's flying license and Kovalenkov's personal one were suspended.

In the meantime, a new force had emerged. A mini-oligarch had come to Kamchatka. If Kovalenkov embodied the old Soviet ways, Stanislav Belan personified the new breed of Russian entrepreneur: many of them fluent in Western finance, pedigreed with MBAs, and protected by foreign passports.

In 2002, Belan had created Bel-Kam-Tour, advertising it as a purveyor of “VIP tourism” on Kamchatka. Things did not get off to an auspicious start. Bel-Kam-Tour's first hotel burned down. But it had been rebuilt, and another, a Swiss-style hostelry with outdoor mineral baths, would open soon. Like a character in a 19th-century Russian novel, Belan seemed to have come from nowhere. The locals knew little about him, except that his two customized Mi-8P helicopters, the first of their kind on Kamchatka, had cost $2.5 million apiece and that his stated country of residence was Switzerland.

People talked of little else. Belan had brought the prospect of a changing order, the hope of a competitive market. Kovalenkov's camp, however, claimed there was nothing fair about the challenge. They had a point: While Krechet was temporarily grounded, Belan's company had suddenly gained exclusive flying rights in the region.

Kovalenkov himself had retreated further into the shadows, eluding my attempts to speak with him. I'd caught him one day on the telephone, but he wouldn't talk. Then, on my last day in Kamchatka, Roman came to me with stunning news. “On vyshel na svyaz,” he announced. “He came on the radio.”

It was just after dawn, but Roman was already frantic. The weekly flight from Anchorage had just arrived, and hunters would need to be serviced. Kovalenkov was doing something unheard of: calling the hunters in their territories, looking for scraps of information.

“Anyone got tracks?” the old boss had asked. “Anyone got kills?” The urgency had surprised Roman, but he understood. “They've taken his eyes,” he said. Along with his license, Kovalenkov had lost his ability to spot trophy bears for his clients.

In the spring, dark bears make slow and easy targets against the white snow for western hunters. Though no one shoots the bears from helicopters anymore, guides are still used to flush animals toward waiting clients, who have snowmobiled in.

It was the Sunday after Victory Day, the celebration of the Soviet triumph over Hitler. The city was asleep, deeply hung over. Roman and I drove out of P.K. along the old route, past the shacks and the birches lashed with bouquets, the plastic memorials to those taken by the road. On the far side of the bay, we came to a sign shaped like a helicopter: KRECHET.

A tall wall enclosed the compound. A guard emerged from the watchtower, where a sizable Caucasian shepherd bared his teeth. Past the gates, I could see half a dozen European-style log dachas nestled along a private lane. The guard pointed at one and said, almost coyly, “Give it a try.”

I walked down the lane, passing the big dachas until I came to one where, inside the square yard, a woman appeared. She nodded warily when I asked if this was where Kovalenkov lived.

The door opened. A figure, taller and leaner than I'd expected, took a hard look at me. It had been a long holiday. His face was covered with gray whiskers, his eyes bloodshot, his shirt half buttoned. But the flair was in evidence. His hair was raffishly long, and a hunting knife hung by his side.

We spoke for a bit, no more than a foot apart on the brick path between two rows of strawberries. I tried to tell him what I'd seen, where I'd been. But he knew it all already. He knew of our flight to the lake, and who'd taken us. He knew, he said, what I was “up to here.”

When I asked about Russell's work, Kovalenkov looked right through me, as if to survey the fields at my back. “I know a thing or two about journalists,” he said. “And I've no use for them.”

He'd had enough. “Next time,” he said, retreating slowly, almost sideways, “we can talk all about your favorite subject┬Śtourism on Kamchatka, its history and troubles.” It was a reference to our first conversation. A grin rose on his face. He seemed younger than a man in his sixties, a gray wolf who, even in the face of the changing tide, refused to give in.

In the months after our trip, Russell bashed on undeterred. Returning to Kamchatka had given him new hope, and the balance of power was shifting. Soon came the biggest news: Kovalenkov had cashed out. News of the deal had spread wide across Kamchatka: the old boss had sold his helicopter monopoly to Kamchatka Airlines, a new conglomerate controlled by Stanislav Belan's Bel-Kam-Tour.

Russell would never forgive the massacre of his bears. But Kamchatka, he felt, might at last be ready for a genuine, small-scale protection program. In late June, he called me on his satellite phone from the cabin at Kambalnoye Lake. He had planned to leave Kamchatka in May, he said, but things had taken “an amazing turn.” He'd hired a Russian, a former hunting guide for Belan whose wife was Russell's biggest supporter in the regional natural resources department, and had managed to adopt five new cubs┬Śthe pair from the zoo, plus another three orphans. This time he would stay until the snows came, to make sure the cubs denned up. He had scant funding, little help, and no guarantee that another experiment would not end in tragedy. But he'd won his plane back, and even though he could no longer fly it in the sanctuary, he was dreaming again. The rehabilitation center for orphaned cubs was, he hoped, becoming a reality.

In long e-mails, composed alone late at night and sent via sat phone, Russell was alternately giddy and distraught. He wrote about watching his five cubs grow, detailing how, on hot days, the one named Sky would escape under the electric fence to swim in the lake; how Buck was a slowpoke, always lagging behind; how Gina and Sheena, the zoo cubs, wandered off for four days; and how he'd managed to save Wilder and Sky from a large predator bear stalking the cabin.

Sometimes it was too much. “I often ask myself why I do this to myself,” he wrote. “What I mean is the stress that goes with trying to look after these cubs and trying to conserve bears in Russia in general.” I read the e-mails and thought of Russell, bad heart and all, chasing a large male grizzly up a mountain to save his cubs.

By late September he was worn out. The predator finally got one cub, Wilder, and though funding still trickled in, the hurdles remained huge. “Enough of my troubles,” he wrote. “I will find a way to survive, alone damn it. Alone. There is nothing quite as saddening as feeling used, old and alone, all at once.” But despite the fatigue, something had come back to life in him. Russell recognized that this new chapter had the potential to end in carnageÔÇölike Treadwell's and Nikolaenko's work hadÔÇöor to redeem all his failings.

“I guess I'm very stubborn,” he told me on the phone in September, “and maybe stupid, too.” Though he was 6,000 miles away, I could hear it in his voice: He would not give up on Kamchatka.

Former Time Moscow correspondent Andrew Meier is the author of . He lives in New York.

Photographs by Gueorgui Pinkhassov.