Atop stormy mountains, on monster seas, in unmapped caves, wherever adventure goes wrong, a cadre of daring emergency rescuers stands ready to step in and save your buttÔÇöeven if it means risking their own lives. Strap on your helmet and jump into the knife-edged world of America's elite wilderness rescue squads: the perils they face, the risks they take, and the stories they tell.

Mike vs. the Volcano

When his best friend died on Mount Rainier, Mike Gauthier set out to do the improbable: turn a ragtag crew of climbing bums into the mountain's guardian angels

“Whaddya think?” Asks backcountry ranger Rick Kirschner. “Lost or dawdling?”

“Hard to say,” says lead climbing ranger Mike “Gator” Gauthier. “The troubling part is that we don't have a record of them checking in at Camp Muir.”

It's a Tuesday morning, 11:08. Mid-July. Kirschner and Gauthier, along with a third ranger, Steve Klump, are sitting around a desk at Mount Rainier's Longmire Ranger Station. Two climbers, Patrick Anderson and Christina Faine, are missing somewhere in the 34 square miles of snow and ice that encases this 14,410-foot volcano. For the past two days Rainier has been its old pre-Prozac self, sulking in a drizzle and hiding behind mist as gray as concrete and nearly as dense. Perfect conditions for getting lost, terrible for getting found.

When mountaineers disappear on the rolling snow field below Camp Muir, the well-trafficked stone bunkhouse at 10,000 feet on Rainier's southern flank, it's often because they've fallen through a slot in Nisqually Glacier or Paradise Glacier, which bracket the trail and are striped with crevasses five stories deep. In 1999, four climbers in three separate parties set out for Muir and never made it back. “Wander too far left and you're dead,” says one ranger. “Wander too far right and you're dead.” After getting a reading from Gauthier and Kirschner on the search-and-rescue (SAR) strengths of the on-duty rangers, Klump decides to put two teams in the field. Gauthier agrees to coordinate things from Paradise Ranger Station and will stand ready with crampons and ice ax if he and his climbing rangers are needed. “I'll call Aero and give them the alert,” Klump adds, referring to the pilots at Aero-Copter, a Seattle helicopter charter service that often assists on rescues.

Gauthier gathers his gear and glances out the window. “Not much else we can do until this lifts,” he says. On his way out the door he passes a government-issue poster: “No Rescue Is Worth Losing Your Life Over.”

In the National Park Service, mountain rescue is a maverick's game. Each of the agency's four most respected climbing SAR teamsÔÇöat Denali, Grand Teton, Yosemite, and Rocky Mountain National ParksÔÇöwas molded by charismatic misfits who spent their lives saving dirtbags rather than following the Park Service's ticket-punching career path. They're rangers like Daryl Miller, who brought together the dream team of volunteers (among them Conrad Anker, Scott Backes, and Alex Lowe) that patrolled the upper reaches of Mount McKinley during the 1990s; John Dill, the legendary head of Yosemite Search and Rescue; Renny Jackson, who posts new routes in the Tetons when he's not peeling gripped climbers off the Grand; and Jim Detterline, aka Mr. Longs Peak (he's climbed the Colorado fourteener 185 times), who runs the high-angle SAR at Rocky Mountain National Park. To climbers, these guys are popular legends who personify the peaks on which they work. To park superintendents, they can be a real pain in the ass.

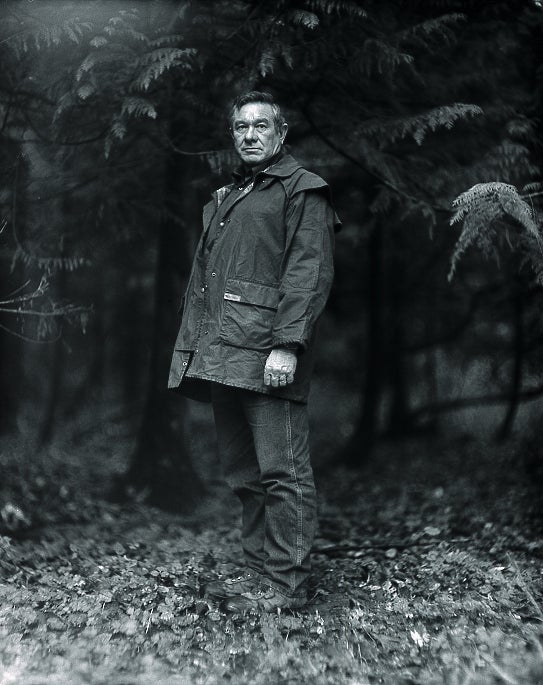

Mike Gauthier fits the mold. A garrulous Navy brat with a wide grin, he bears an uncanny resemblance to Stifler from the American Pie moviesÔÇöstrong jaw, broad foreheadÔÇöbut without Stifler's jackass qualities. Half the climbers on Rainier know him. At Camp Schurman or Camp Muir, the high aeries where Gauthier and his squad of 12 climbing rangers eat, sleep, and hold office hours, a dozen climbers a day will knock on the hut and ask, “Gator around?”

If Gator's around a little less than usual lately, it's because success is taking him away from “the hill,” as the climbing rangers call Rainier. At 32, he has emerged as a leading figure among the next generation of mountain SAR professionals. Over the past six years he's taken Rainier's moribund climbing ranger program and turned it into a model for SAR organizations nationwide. Between his duties as captain of Rainier's high-mountain SAR squad, he can be found giving crevasse-rescue classes or leading wilderness seminars at Reid Thorne's famous Ropes That Rescue school in Arizona.

“Would I want him coming after me? Absolutely,” says Daryl Miller, head climbing ranger at Denali. “As a climber, he's able to do anything and everything.”

It wasn't always this way. Twelve years ago, when Gauthier signed on as a climbing ranger at Rainier, the job involved little climbing and a lot of ticket-writing in the Paradise parking lot. Most “climbing” rangers summited a few times a season, if ever, and hard-core mountaineers viewed them as officious dilettantes. Rainier Mountaineering Inc.'s Everest-caliber guides, who traditionally ruled the mountain, didn't trust them on a rope. Park managers were fairly clueless about the upper mountain and gave the rangers little backup. Training was minimal; equipment, sparse and creaky. Gauthier even sees his own hiring as a sign of the malaise.

“I was a 20-year-old with a ponytail and a leather jacket,” he recalls. “I'd done a couple peaks in the Olympics and Cascades, but I didn't have anything approaching decent climbing experience.” Born and raised on the Olympic Peninsula, he picked up the nickname Gator from a football coach who couldn't pronounce Gauthier (GO-tee-ay), and as he got older he grew into itÔÇöa nice way of saying the guy's got a big mouth. At 15 he gabbed his way into a seasonal job at Olympic National Park, where he worked as a backcountry ranger for four seasons before coming to Rainier. Once on the mountain, he apprenticed with Cascade hardmen like Pat Timson, who taught him to climb light and fast, and Paul Baugher, an avalanche expert who ran Camp Schurman in the 1980s when guys like Mark Twight were hanging around, climbing ice in the crevasses.

Gauthier used his time to build his own skills, eventually becoming so comfortable on the glaciers that he could literally run down them. But the more he sharpened his own mountain acumen, the more he felt the sting of disrespect from the Rainier veterans. The weakness of the NPS climbing program was exposed in August 1995, when Gauthier's best friend and climbing partner, Sean Ryan, a 23-year-old rookie climbing ranger, and Phil Otis, a 22-year-old student volunteer, charged out of Camp Schurman to rescue a climber who'd broken his ankle just below the summit. Ill-trained, inexperienced, and poorly equippedÔÇöOtis had attached his crampons with duct tapeÔÇöthe two lost their balance on a windy section of glare ice on the Emmons-Winthrop Glacier and were killed in a 1,200-foot fall. Gauthier had been out of the park when the distress call came, and he took their deaths hard. But after months of soul-searching, he rededicated himself to turning the climbing program around. “I was young, passionate, and pissed,” he says. “I wanted to fix what was broken, what had contributed to the death of my friend.”

His boss agreed to let him hire the next year's climbing team. It was a put-up-or-shut-up move, and Gauthier put up. He recruited a crew of nonconformists who bristled at wearing a stiff uniform but could climb like madmen. No one exemplified the new guard better than David Gottlieb, a tall, rangy mountain freak from the North Cascades whose idea of personal grooming was to tug on a knit ski cap. When people asked about the “Question Authority” button on his government-issue uniform, he would smile and say, “We're the authority. Ask us questions.”

Tuesday, 2:36 P.M. Kirschner works the phone to glean data from the missing climbers' friends and families. “What about the color of their jackets?” he says into the receiver. “Mmm-hmm. Do you think she'd hunker down in a storm or keep going?”

Kirschner builds the profile: tent color, jacket color, hat color, experience, character, equipment. Klump, Gauthier, and Steve Winslow, another climbing ranger who has now joined the effort, plot possible moves on a topo map. An hour passes. Along the rocky moraine of the Nisqually Glacier, the clouds part just long enough for rangers Dave Turner and Dan Keebler to spy movement across the ice.

“Two people are around a tent at 5,900 feet,” Turner crackles over the radio. “Extremely challenging to get over there.”

Radio silence while the rangers downclimb the cliff onto the glacier. When they call in again, they have something.

“Looks like we got one person here,” says Turner. “With snowshoes and a snowboard. In the waterfall. Code black.”

A dead body. Jaws drop roomwide.

One of Gauthier's biggest challenges on Rainier was to somehow get his NPS supervisors to sign off on his ragtag band of climbersÔÇöa process that required him to be a bit of a punk. Ushering Gottlieb and the others up to the climbing camps, Gauthier and Winslow molded them into professional rangers without squeezing the climbing juice out of them. “I knew if they could just get through the application paperwork, they'd get up and kick ass on the hill,” Gauthier says.

Ass was kicked. The new climbing rangers each pushed 15 to 35 summits a season. They climbed hard routesÔÇölike the 4,000-foot, 60-degree Mowich FaceÔÇöfast, on duty and off. When they talked to mountaineers at Schurman and Muir, they spoke the language, knew which equipment was bombproof, and provided reliable beta on the routes. They lived in the high huts, coming down only to resupply and bathe. NPS higher-ups soon took note that the ranger program wasn't just a federal grant for climbing bums.

On June 11, 1998, after three years of training, the new SAR crew got its test when an avalanche swept ten RMI climbers down Disappointment Cleaver, a steep section of icy rock at about 12,300 feet. Gauthier heard the radio distress call on the summit, which he'd just climbed solo on his day off. He strapped on his snowboard and 23 minutes later was the first responder to a chaotic scene: Climbers were dazed and bleeding and one team dangled off a cliff, held precariously by a badly frayed rope. Gauthier had already set up an anchor and stabilizing ropes by the time two more climbing rangers choppered in, followed closely by RMI honchos Lou and Peter Whittaker and their friend Robert Link, an Everest veteran. Together the RMI team and Rainier's climbing rangers got all but one victim down alive.

“We've seen a dramatic change in their program,” says Peter Whittaker. “The quality of the climbing rangers at Rainier today is exceptional. They're no longer parking-lot rangers.”

Tuesday, 2:40 P.M. Klump hears the code-black call and picks up the microphone. But before he can say anything, Turner cuts in.

“Ah, upon closer inspection, it looks like…” Pause. “A pretty old body.”

A ranger listening in on the other side of the mountain breaks radio etiquette to ask: “Did you say old body? Not a live person?”

“Affirmative,” says Turner. “I see snowboarding boots and snowshoes.”

Winslow says it first: “Teej.”

The room goes churchly quiet.

“The doctor.”

William Tres Tietjen, a 28-year-old physician from Georgia, disappeared while snowboarding the Muir Snowfield on June 20, 1999. He was last seen leaving Camp Muir in near-whiteout conditions. Searchers combed the glaciers and snowfields for a week and didn't find a trace.

For a few minutes the SAR team feels its problems compounding: a dead body and two still-missing climbers. Klump tells the rangers to note the location of the corpse and keep after the missing pair. Ten minutes later Turner and Keebler come back with news. “Search base,” radios Turner. “We have the missing partyÔÇöin good shape.” Reaction around Paradise is muted, an indication of the rangers' stoic professionalism; the real emotions are kept in the bank for future SAR operations with bigger challenges or less-than-happy endings.

While the rangers guide Anderson and Faine off the glacier, Winslow puts together a team to recover Tietjen's remains. It will take nearly a dozen rangers more than three hours to remove his waterlogged body and gear.

On Wednesday Anderson and Faine, the rescued pair, show up for work with stories to tell. They got a late start on Saturday, and nasty weather began closing in when they reached Camp Muir. They pushed on for another half-mile before turning around; on the way down they strayed off route. Afraid of going too far left onto the Paradise Glacier, Anderson had overcorrected and led them onto the Nisqually. Trapped in a whiteout with crevasses all around, they pitched a tent to wait out the weather. By the time Turner and Keebler reached them on Tuesday afternoon, they were down to half a bagel and two Rolaids.

In a desk drawer at his office, Gauthier keeps a folder of letters from people who owe their lives to him and his crew. Sometimes after a rough op he'll pull out a couple to remind himself that a good day on the job means a father will see his son again, or in this case that two mountaineers will live to climb another day. This time there's no need to reach for the file.

“You walk home high on endorphins,” he says. “And the next day you show up at work and it's business as usual.”

ÔÇöBruce Barcott

Crawl Space

You're trapped underground with an inch of air to breathe? Relax. Buddy Lane is on the way.

For 18 hours, David Gant bobbed in the blackness, his head pressed against a wrinkle in the limestone ceiling. His scuba tank was out of air, his headlamp out of juice. The oxygen in his tiny crevice was thinning dangerously. He was growing dizzy, on the brink of unconsciousness.

Gant was a 31-year-old Alabama logger who'd dabbled in scuba diving but had no experience with caves. Late the previous night, August 15, 1992, he'd gone spearfishing with a friend in the mouth of a flooded cave on the edge of Nickajack Lake, not far from Chattanooga, Tennessee. The fenced site warned trespassers of $25,000 fines, but local legends of 200-pound catfishÔÇöreputedly fattened on a food chain enriched by guano droppings from resident gray batsÔÇöwere too tantalizing for the two friends.

At some point, one of the spearfishermen stirred up silt and the entrance clouded to “zero viz.” Panicked, Gant's friend swam out of the murk and sought help. Gant unwittingly swam into the cave, bumping his tank along the ceiling until, several thousand feet in, he found a cavity. Exhausted and scared, he grabbed on to a stalactite and started treading water.

By the time cave-rescue specialist Buddy Lane arrived on the scene the following day, he recalls, the local incident commander had declared the operation a “recovery.” In his judgment, it was inconceivable that Gant was still alive. Open-water divers had probed the initial cave passages, and now authorities were dragging the depths for the victim's body. Nearly a hundred people, including distraught members of Gant's family and a welter of TV reporters, were gathered around the site. It was a deathwatch.

Lane strongly advised the incident commander that it was premature to regard Gant as a corpse. The captain of Tennessee's all-volunteer Hamilton County Cave Rescue Unit and perhaps the nation's preeminent subterranean rescuer, Lane had seen too many situations like this. His team was the firstÔÇöand for years, the onlyÔÇötrue cave-rescue unit in the country. Over the past 18 years, this well-traveled speleologist had spearheaded or participated in some 150 underground extractions, including the longest, deepest, and most technically trying cave rescue ever undertaken, the nationally reported evacuation of an injured explorer from New Mexico's Lechuguilla Cave in 1991. Lane approached the crisis at Nickajack with coolheaded precision. Earlier that day, he'd gotten hold of an old map, surveyed by the Tennessee Valley Authority before Nickajack Lake was created in 1969. The map's vertical profiles convinced Lane there was a chance the cave had air pockets where Gant could still be breathing. “I thought of myself there, all alone while everyone outside was declaring me dead,” Lane recalled.

Lane's next step was to contact a state emergency official who, in turn, persuaded TVA to do something extraordinary: open the floodgates of Nickajack Dam to bring down the level of the 30-mile-long lake. The utility authority had never done anything like this before; it was a quarter-million-dollar squandering of reservoir water earmarked for hydroelectric power. Yet opening up the dam, Lane felt, was the only chance to turn a recovery into a rescue.

Once the waters began to recede, Lane was itching to search the cave. Although no one among the emergency crew at Nickajack had advanced underwater cave rescue experience and Lane was eminently capable of making the dive, he was told to remain on standby. Lane eventually persuaded the incident commander to let his unit explore a few of the cave's newly dry side passages; then he and his team lieutenant, an impressively mustachioed park service cop named Dennis Curry, put on float vests and slipped into the lake.

The two rescuers finned their way 2,000 yards in, to the point where they had but a few inches of airspace. With waning optimism, Lane swirled his searchlight over the far reaches of Nickajack Cave, and crept ahead.

It's no coincidence that the nation's foremost cave rescue team is based in Chattanooga. The Civil War city, set in the hard limestone crotch where Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia wedge together, is one of the leading karst regions of the world. Some 8,000 caverns are known to exist within an hour and a half's drive of ChattanoogaÔÇöand it's anyone's guess how many are yet to be discovered.

A native Chattanoogan, Lane went on his first caving trip when he was 15. “I knew immediately it was my calling,” he says. Now 47, he is a large, gangling man with thinning dark hair and a wry grin that lingers on his face as if there's a punch line coming. He runs a steel-fabrication company, which has afforded him the financial freedom to range widely over the planet, “sport pitting” wherever the caving's goodÔÇöAlaska, Switzerland, Belize, Honduras. He has a prosthetic left eye, the result of a brutal facial injury he sustained while caving in Tennessee in 1975. His various scrapes and close calls have convinced him that, in the end, “cavers have to look after our own; no one else is going to come after us when we get in a jam.”

Lane participated in his first cave rescue in 1973, and he was instantly hooked on its gritty intensity. Cave rescues, he learned, are laborious affairs requiring, among other things, extensive rock-climbing skills, intricate belays, and specialized litters. Communications are difficult at best, since ordinary radio and cell-phone signals don't travel far through rock. Rescuers often face the tricky task of squeezing the injured person through constrictions no wider than a man's shoulders, or hauling the victim up through gelid waterfalls. Every piece of equipment that might be needed must be hauled underground.

During big, complicated rescues, Lane typically spends most of his time aboveground, choreographing the efforts of law enforcement and emergency response crews. He is known as a quiet, analytical field general whose mobile command post is a cobalt-blue Chevy Suburban turbo diesel crammed with electronic equipmentÔÇötwo cell phones, two global positioning devices, a public-service radio, a police scanner, several pairs of walkie-talkies, a console-mounted platform for his laptop, and a voice-activated tape recorder to capture distress calls.

Of course, not all cave extractions are rescues. Last July, Lane was called in to retrieve the body of a Tennessee man named Jeffery Wayne Young, who had committed suicide in a pit beneath Gum Springs Mountain. A reputed methamphetamine user, Young was missing for three weeks when his Rottweiler, Spike, was discovered (alive, but emaciated) inside the cave entrance. Lane, along with Curry, finally reached the 60-foot pit where Young had plunged to his death, and began the grim, dangerous business of hauling the corpse out of the hole. “The rock was rotten, and so was he,” Curry says. “Even with two body bags, I couldn't get enough Vicks VapoRub in my mustache.”

All types of people end up stranded in caves, some of whom Lane politely calls “doofuses.” In 1997 Lane and Curry cave-rescued a young, reefer-befogged man wearing cowboy boots who, in a series of remarkable maneuvers, managed to get himself in a crouched position with his head pinned between a wall and a 500-pound boulder. How do cave rescuers feel about risking their necks to save people who, in a strictly Darwinian view of things, may not deserve the effort? “I let God sort that out,” Curry says. “My thing is, I don't want them littering up the pristine caves.”

Lane puts it another way: “Even doofuses are entitled to a second chance.”

David Gant briefly lost consciousness after 13 hours' floating in Nickajack Cave. Yet in what seemed a near-miraculous stroke of good timing, he was revived by a fresh breeze that came whistling through the passage. Gant clung to his stalactite for another five hours until he experienced a spiritual vision. He was dyingÔÇöhe was quite sure of it. The cave became a white tunnel. A pair of intensely bright lights approached. Everything was clear to Gant as he peered into the blinding luminance. “You're angels, aren't you,” he said, “coming to take me away.”

“Dude,” Curry replied, “we've been called a lot of things, but never angels.”

Slowly, the three men breaststroked out of the cave. When they emerged into the late afternoon glow, the deathwatch was still in progress. Hundreds of people along the banks turned in stunned amazement. Waterlogged and weak, Gant stumbled ashore and embraced his family.

Lane and Curry packed up the rescue truck and left. Meanwhile the media at the site flocked around Gant and his relatives; the press would soon herald the event as the “Miracle at Nickajack.”

Lane's official report was considerably more understated. “Found victim alive,” he wrote. “Everybody happy.”

ÔÇöHampton Sides

Every Step You Take

Mystic, taxonomist, master of dirt, Joel Hardin knows where you areÔÇöeven if you don't

Along about the 12th hour of classÔÇöafter our instructor, Joel Hardin, has whittled six or eight sticks of pine down to toothpicks and after the elderly student lounging beside me in the sparse shade of the ponderosas has fallen asleep (and starts snoring, his handlebar mustache twitching in somnolent spasms)ÔÇöI suddenly apprehend the commonsense magic of wilderness man-tracking.

“Humans are a unique creature,” says Hardin, 62, a paunchy retired cop and the reigning maestro of the tracking universe. “They're the only creature in the world that acts on education and knowledge, but generally they don't do wild and funny things like leap from rock to rock to hide their footprints. And if they doÔÇöwell, you can look and tell where they went on and where they went off. All the evidence is there on the ground.”

Shazam! My seven classmates suddenly cant forward in suspense. These people are the tracking-world equivalent of Ph.D. candidates: SAR volunteers who have spent at least 400 hours each in classes run by Hardin, the chief instructor for Universal Tracking Service, a mobile school based in Everson, Washington. My classmates have all earned their Track Aware, Tracker I, and Tracker II pins; they can follow footprints for miles in the dark in a dust storm. But they're here now, on this hot September weekend, amid a cluster of Forest Service cabins at Camp Cody in the Central Oregon woods, in hopes of attaining the pi├Ęce de r├ęsistance of Hardinometrics: the Sign Cutter pin. A Sign Cutter, according to UTS's arcane guidelines, can prevail over “conflicting, confusing, disorganized, and misleading information” to decipher vague scratchings on the ground. My classmates want wisdom, and Hardin, who has tracked more than 5,000 individuals in the last three decades, feeds them another morsel.

“People don't levitate,” he says. “People got two legs and two feet, and that's how they get around on this earth.”

A murmur of wonder ripples under the pines, for Hardin is correct. Our species has been leaving tracks in the dirt ever since we departed from the Garden of Eden, presumably on foot. Indeed, in his new book, The Art of Tracking, South African writer Louis Liebenberg argues that the earth's first trackers, the Kalahari of prehistoric southern Africa, were also the planet's first scientists: In analyzing footprints, they anticipated the physicists who today “track” subatomic particles.

Whether or not that's true, tracking has become the most esoteric discipline in the SAR tool kit. Fewer than 1,000 Americans are currently active man-trackers, and while most volunteer for county rescue squads, many belong to either the woo-woo fringe or the paranoid right. Among the former are the disciples of Tom Brown, the New Jersey naturalist who comes close to claiming that one can, by communing with a footprint, divine what its maker ate for breakfast; among the latter are the prot├ęg├ęs of David Scott-Donelan, a former Rhodesian counterinsurgency specialist whose Nevada tracking school begins with the premise that the “quarry” is “ARMED and DANGEROUS.”

Between these two extremes, in more or less the same slot as meat and potatoes, sits Joel Hardin, whom Linda Hunter, a director of the International Society of Professional Trackers, calls “the nation's best search-and-rescue tracker, the elite of the elite.” Hardin began honing his craft in 1965, when he was hired to chauffeur the U.S. Border Patrol's tracking squad through the California desert. The Patrol trackers were a tightly knit, ultramacho fraternity; they aimed to keep their skills secret. Hardin learned anyway, and then he spent a decade chasing Mexican ├ęmigr├ęs as they fled their homeland on foot, on stilts, and in shoes tied to cow hooves. He has since tracked a murderer trained in erasing his footprints, a Boy Scout who got lost at the Idlewild Jamboree, and a former Bulgarian freedom fighter who moved to America and holed up in the hills of Washington state, subsisting on huckleberries and slugs in between robbing people's homes.

When you query Hardin about such successes, he mostly just shrugs and spits at the ground. Such behavior reminds you that tracking is not romantic; it's just a matter of staring at dirt. And that very endeavorÔÇöstaring at dirtÔÇöis the featured activity of my weekend in the Oregon woods. Day and night, my classmates follow “lines of sign,” elaborate footprint-stories, through the cheatgrass and pine needles. One group of students dreams up fictional scenariosÔÇöa fugitive takes to the woods, sayÔÇöand then tramps the tale into the dirt for the others to puzzle over. Sometimes students pause to sketch a shoe sole on an index card; sometimes they use a “tracking stick” (a ski pole with lines on it) to measure the distance between strides.

The work does not make for rousing spectator sport, but Hardin nonetheless spends hour after hour leaning against a cedar fence rail, watching. When one of his acolytes goes off-course, he says nothing. He merely strolls up behind the person and flicks a pine needle high in the air, so it flutters in the sunlight and lands right where the student is supposed to be lookingÔÇöa deft gesture, and also a warm one, in a languorous, country sort of way.

Hardin grew up in Emmett, Idaho, hunting and fishing. He worked as a cop after high school and sharpened the interrogational techniques that are, he says, still the most crucial of his SAR skills. “You have to ask the right questions at the beginning so you don't go down the wrong path,” he says. “One time, a woman reported her husband missing; he'd hiked up a mountain to take photos at dawn. I could've just rushed out, but I asked, 'What kind of camera did he have?' It comes back that it was a cheap point-and-shoot. I got myself another cup of coffee, then I said, 'What'd he do Friday night?' It turned out that he'd walked through wet grass; he knew it was rainyÔÇöbad photo weather.” His verdict? “Tell the lady to look in the closet,” he said. The guy's clothes were gone. He hadn't gone hiking; he'd split.

Sometimes, of course, “lost” people truly are lost. And when it gets that serious, Hardin's abilities border on the supernatural. In 1999 he tracked an Alaskan home-builder named Robert Bogucki through the Australian outback. Bogucki had stepped into the bush with little more than a Bible and a hope to “sit down and let my mind go free.” His parents first caught wind of this dubious vacation scheme from the Australian police, who spent two weeks looking for Bogucki. When the Aussies didn't find him, his parents called in Hardin, who followed month-old tracks across 160,000 square miles of wilderness. Gradually he came to respect Bogucki's conviction.

“He was levelheaded,” Hardin says. “He had a route, a straight line, and he'd deviate from it, sometimes for 15 miles, but always he'd retrace his steps. I got so I could tell where he stopped to rest and where he sat with his maps and began to doubt his navigation skills.” Hardin's crew followed the line in helicoptersÔÇöthrough canyons and over vast thickets of knee-high grassÔÇöand on the fifth day they found Bogucki, in good health. “Joel wasn't just looking for me,” Bogucki marveled afterwards. “It was like he was out there taking the trip with me.”

At Camp Cody all my classmates and I can do, really, is huddle together in plebeian awe. Finally, on Sunday morning, Hardin announces (apologetically) that once again no one in camp will be receiving the elusive Sign Cutter pin. He offers no exact explanation, but a week later I call and press him to define what he really wants in students.

“Well,” Hardin says, “I guess you could almost call it clairvoyance.”

“That's impossible,” I say.

Hardin laughs. “Well,” he says, “it's almost impossible.”

ÔÇöBill Donahue

The Sweet Smell of Success

Think the odds of surviving an avalanche are impossibly slim? Don't bet against Keno.

On December 19, 2000, roughly 24 hours before opening day at British Columbia's Fernie Alpine Resort, lift operator Ryan Radchenko skied off-limits on his lunch break, triggering an avalanche that carried him 450 feet before burying him alive. A patroller who witnessed the slide put out a radio call to summon Keno, snow-safety supervisor Robin Siggers's five-year-old SAR-trained Labrador/Border collie mix, who was whisked from the base area by snowmobile. Siggers, who was already on the mountain, took a lift to the scene and began assisting with the search. “I was well aware of the statistics,” he says. “I was praying Keno would arrive soon.”

There are more than 2,000 trained SAR dogs in North America, and they often prove invaluable during desperate, time-limited searches. At Fernie, despite ten rescuers frantically thrusting eight-foot probes into the debris pile, they'd turned up nothing by the time Keno arrived 18 minutes later. The dog immediately bolted 30 feet below the probe line and emerged with a leather glove in his teeth. “He's trained to dig like crazy when he finds a person,” says Siggers. “About a foot below the surface, he uncovered Ryan's hand.” The rescuers pulled Radchenko out, semiconscious but unhurtÔÇöthe first live avalanche find by a rescue dog in Canada. Keno, though, had an insider's odds: The previous summer, Radchenko did carpentry work with Siggers at Fernie, telling Keno repeatedly, “Hey, you'd better get a good sniff in case you have to find me someday.”

ÔÇöKi Bassett

Chopper Queen

Few people could qualify to pilot a Jayhawk HH-60. Kodiak Lieutenant Commander Melissa Rivera flies one in the toughest conditions in North America.

An hour before a routine training exercise in which she'll drop rescue baskets from her copter onto a Boston Whaler thrashing 20 feet below in rough Alaskan chop, Lieutenant Commander Melissa Rivera strides across the tarmac at the Coast Guard's Kodiak Air Station and begins inspecting her twin-engine HH-60 Jayhawk. Starting at the tip of the 14,000-pound needle-nosed mosquito, with her frizzy brown hair tamed into a French braid, Rivera shimmies up the hood to check that the engine hatches are firmly closed, scans each rotor blade for cracks, and eyeballs the fuel and oil levels.

On board a few minutes later, Rivera reminds the copilot and crew about emergency procedures should they, say, chip their tail in rough water, plummet into the ocean, and flip upside down. “If we ditch,” she reports matter-of-factly over her headset, “it will be a left-side egress.”

As one of only three women out of the 70 Coast Guard pilots stationed at Kodiak, Rivera, 31, is responsible for saving everyoneÔÇöfrom stranded fishermen to mauled bear hunters to downed bush pilotsÔÇöacross four million nautical square miles of Alaskan territory. Flying for the Coast Guard anywhere is rigorous, but a posting at Kodiak is considered the toughest assignment in the service. The sheer size of the coverage area means that Rivera's missions can begin with 12-hour, thousand-mile relay flights just to get to an accident scene. And she'll routinely fly in total darkness and severe winter storms over terrain that lacks the navigational crutches like streetlights and flashing antennas that aid her counterparts in the Lower 48. The conditions turn even veterans into greenhorns. Despite six years of experience and an Air Medal earned in 1999 for plucking 47 North Carolinians off treetops during Hurricane Floyd, Rivera, like every other newly arrived Kodiak flyer, spent the first winter in the copilot seat. You need a full season under your jumpsuit before you get any respect up here.

Helicopter search and rescue was initiated in 1944, when the Coast Guard introduced the first recovery hoist, enabling choppers to offer rapid assistance to stranded victims at such previously impossible-to-reach spots as rough coastline, roadless wilderness, and high-altitude passes. Today, with specimens like Rivera's Jayhawk, a $16 million salvage-specific chopper that can cruise up to 180 knots one minute and steadily hover as low as ten feet off the ground the next, the helicopter remains the SAR vehicle of choice. Last year, Kodiak teams completed 210 missions, and saved 113 lives.

On the downside, the annual increase in lifesaving flights has also meant escalating danger to lifesavers. Lest Kodiak pilots forget this fact, a memorial mural in the base's central hangar provides a dark reminder. The fresco of choppers hovering over a flailing fishing boat depicts the downing of, among others, Helicopter 1471, which plummeted into Ugak Island in 1986 while its crew was trying to help a sinking ship, even after their electronics cut out. All six crew members died.

“We know stuff like that can happen, but we are trained to assess the risks,” Rivera reasons, sitting in the cockpit. “Just because I'm getting in my [helicopter] doesn't mean I'm going to do something if I determine it's too risky to the crew.”

Risk assessment, however, didn't keep her grounded when U.S. airspace was closed after the September 11 terrorist attacks. The next day, Rivera received special clearance to fly to Akutan, a remote town 750 miles southwest of Anchorage, where a cannery worker was unconscious from a bleeding ulcer. “Normally when you fly in Alaska there are lots of planes and nonstop radio traffic,” she says, “but that day it was so quiet it was eerie.” By the time they landed, the man had lost 40 percent of his blood; en route to the hospital, after the crew hooked up an IV, his blood pressure leapt from a near-death 60/30 to a stable 110/70. Rivera, who estimates she's helped save about 75 lives in her six years as a pilot, shrugs it off as a “routine mission.”

Kodiak pilots can be laconic about the dangers they face, and Rivera, a mother of two who flew missions until she was six months pregnant, is no different. Adrenaline-pumping challenges are the reason the handpicked crews came here in the first place. “You get a certain amount of respect in the Coast Guard being a pilot,” Rivera concedes. “But being an Alaskan pilot, it's a whole other level.”

ÔÇöNatasha Singer

Follow No Leader

Chuck Demarest and his colleagues won't take orders, don't wear uniforms, and each year handle more missions than any other volunteer SAR squad in America

When Chuck Demarest's pager goes off on an Indian Summer Sunday afternoon in Boulder, Colorado, he happens to be at a barbecue with 40 other members of the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group. All around Demarest, beepers start beeping, like a scourge of electronic locusts. Plates of potato salad and bratwurst are set down, and men and women dressed in running shoes and T-shirts smile at one another as they trot down the flagstone steps and hop into their vehicles.

The call is no surpriseÔÇöRMR, which completes roughly 80 missions a year in and around Boulder County, is one of the busiest volunteer mountain-rescue squads in the nation. But the scene is still a little bizarre. For one thing, none of the rescuers looks like the character played by Sylvester Stallone in Cliffhanger, the 1993 movie about a mountain-rescue team not-so-coincidentally named Rocky Mountain Rescue. More than half the people at the party are engineers; most others are researchers and computer programmers. No matter their ageÔÇömost of the 63 members hover somewhere between 25 and 30ÔÇöthey all look, well, wonkish. Sixty-four-year-old Bill May, for instance, the barbecue host, is rail-thin, sports big metal-framed glasses, and is a retired engineer who wrote the essential book on wilderness rescue, Mountain Search and Rescue Techniques. Dave Hibl, a 49-year-old orthodontist who's helped develop much of the group's gear, including its litters and winches, displays the conservative haircut and mild-mannered earnestness of Clark Kent. And Jenny Paddock, 39, a serious, compact woman with cropped graying hair, happens to be a Boulder police officer and one of the most highly respected search-and-rescue dog handlers in the state. Pre-verbal Italian stallions they're not.

Even more unnerving is the fact that no one is wearing a uniform, or even a patch, and no one seems to be in charge. There's none of that militarized protocol so common in the crack emergency teams Hollywood loves to confect. “We're all-volunteer,” says Demarest, clearing up the uniform matter. “We don't like to take orders, and we don't need direction. We're like well-ordered ants.”

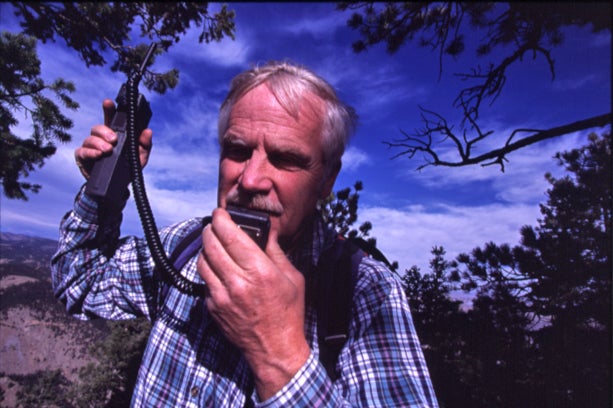

I follow Demarest to his car. At 58, he's strongly built, with steady blue eyes and a sandy mustache going gray. But even as RMR's longest-term active field member, he doesn't seem to fit the preconception of a rescue jock. A Princeton alum who did graduate work at the University of Colorado in nuclear physics and has trained in classical piano all his life, Demarest is a director of a venture-capital firm that's investing in a treatment for Parkinson's disease. As we pile into his car, a sedate Subaru sedan with a cracked windshield, he hits the VHF public-safety radio, which is already crackling with information about an incident in the foothills above town. A hiker has been mauled by a bear but is talking to authorities on his cell phone.

Like everything else about Demarest, the Subaru runs counter to what one might expect, but it serves its purpose well. “I've got everything I need for a couple of days in the mountains,” he says as we pull out. This includes boots, headlamps, ice axes, a bivy bag, sets of maps, granola bars, radio, and GPS. “I've even got the directions for the GPS, in case I get stupid,” he says. Fat chance. Rescue attempts in any season are completely second nature to Demarest. He's been on more than a thousand missions, and he's seen almost every imaginable scenario. He's found downed aircraft in the middle of the night during the dead of winter, and he's down-climbed at dusk onto a ledge above timberline to spend the night with three half-starved and terrified hikers. He stands ready to get pulled away from job or family, day or night, on a moment's notice. “Our motto is 'Join RMR and see Colorado by headlamp,'” he says. “It's true, but it's a tremendous service and a great way to give back.”

Demarest hits Broadway, one of Boulder's main thoroughfares, and turns north, jockeying through the weekend traffic. He listens to the radio as the hiker's description of his surroundings is updated. The hiker is walking out under his own power but can't say exactly which trail he's on. Rescuers have deployed to the head of the Bear Canyon Trail, but Demarest decides to drive farther south to Lower Skunk Canyon. “I've got a hunch,” he says.

Pressed about the unsettling lack of a command structure, Demarest just grins: “The truth is, we're so darned experienced we don't need it.” History backs him up. The weekend before, for instance, a climber fell off a rocky outcrop near Elephant Buttress up in Boulder Canyon. The victim called in the accident on his cell phone, the 911 dispatch paged RMR, and five minutes later the first rescuer was at the base of the climb. Within a half-hour, 20 more volunteers and the group's four-by-four vanÔÇöa Swiss Army knife of a vehicleÔÇöarrived with enough rescue, first-aid, and computer mapping equipment to outfit an expedition. Two rescuers scrambled up to the ledge with a first-aid pack, and one stabilized the victim, who had a head injury, while the other scouted an evac route and radioed for a litter and oxygen. Above and below, RMR members fixed ropes, a litter team swiftly assembled, and the injured climber was strapped in, lowered 300 feet, and carried through Boulder Creek a quarter-mile to an ambulance. All told, the victim was evacuated in less than 90 minutes.

While they specialize in high-angle evacs, over the years RMR has found hundreds of lost hikers and led the country in locating wrecked planes. In 54 years of technical operations it has incurred only one serious injury among its rescuersÔÇöa broken leg. “Our most common worker's comp claim,” Demarest jokes, “is poison ivy.”

Demarest turns on a winding paved road up into the broad tawny meadows at the base of Boulder's Flatirons, beautiful jagged slabs of upthrust sandstone. He jogs up a dirt trail behind some high-end redwood-sided mountain homes. Sure enough, here comes the hiker, looking dazed, his shirt in shreds. But Demarest is too lateÔÇöthe hiker is already being helped by two RMR rescuers who have somehow beaten Demarest up the trail. The man is shaken up, they say, but unbloodied. He was lucky: A black bear sow had shoved him onto the ground after he'd gotten too close to her cub, looked him in the eyes, and hustled away. “You see,” Demarest beams. “They know. Nobody needs to order anybody anywhere.”

ÔÇöPeter Heller

The Jed Zone

No publication arouses as much antici-pation among the editors in our office as the annual Accidents in North American Mountaineering. Each year, ANAM is filled with tragic accounts of mishaps in the mountainsÔÇöbut the esteemed report is also salted with enough cautionary tales and strange twists to make it a must-read source of indelible lore. (And, truth be told, of ghastly humor.) We caught up with longtime Accidents editor Jed Williamson at his office at Vermont's Sterling College.

OUTSIDE: So What's the primary purpose of publishing these reports?

Williamson: Education. It's a tool by which people can think about their climbing. While the data isn't so much statistical, it can show trends.

One of which is the increase in rescues initiated by cell phones. Do you think people have a responsibility to use available technology?

Technology shouldn't substitute for having the right gear and making reasonable judgements. One time people called a ranger saying, “We need to know how to get to a certain trail. We have a GPS with us.” The ranger says, “Great. Get that out and get your map out.” And they say, “Oh, well, we don't have a map.” You follow my drift?

Any other trends you're seeing?

Well, there's the conversion to climbing protection that costs about 45 bucks apiece. I talked with some of the climbers whose reason for injury is because protection pulled out. I started asking, “Are you putting it in all the way?” A lot of them sheepishly say, “Well, no. I was afraid I might not be able to get it back out.” They didn't want to lose money. That's a false economy!

Last year, you published an incident about a guy trying to climb Denali carrying a bamboo pole to keep from falling into a crevasse…

Oh, yeah. That was a case where the guy had no experience whatsoever. But these are the people that the park service has to deal with. There was once a kid who wrote to the park, “I'm planning to climb Mount McKinley. What I'd like to know is, One, Is there snow on it all year round? Two, Will I need to make camps along the way? Three, Should I bring grommets with me?” We had no idea what “grommets” meant.

Is there anything you won't print? Like that frightening tale about Tom Hornbein and the beer can?

Well, I actually put that one in the book. I wrote, “The individual used a Foster's beer can as a pee can, and got his member caught in there.” And to conclude, I wrote, “All members of the expedition have recovered.” This summer, Hornbein admitted he'd pulled a fast one on me. But it was a hell of a good story.

ÔÇöChris Keyes

Hey, Wanna Get Lost? No Problem!

Just commit these eight blunders to memory.

1. Fail to pay attention:╠ř“One of the main reasons people get lost is that they just don't keep looking around and striving to maintain a constant awareness of their surroundings,” says Rocky Henderson, president of the Mountain Rescue Association. “I call this the 'head-in-the-cockpit syndrome'. My advice? Be aware of your surroundings, and try your best to save the extraordinarily stupid moments for when you're at home sitting in front of the television set.”

2. Leave behind the Ten Essentials:╠řSays Charley Shimanski, Education Director for the Mountain Rescue Association: “Whenever you pack a pack, be sure you have the Ten Essentials [map and compass, flashlight/ headlamp, extra food and water, extra clothes, sunglasses, first-aid kit, pocketknife, waterproof matches, fire starter, emergency shelter]. If you have all of these things, chances are good you'll have what you need in an emergency.”

3. Don't learn how to read a map and compass:╠ř“I run into people all the time who have a map but really just don't know how to use it,” says veteran tracker Hannah Nyala. “Don't bother bringing it if you don't know how to read it.”

4. Panic:╠řSays Nyala: “When people get lost, their brains start running so fast they forget the simple things like putting one foot in front of the other. This leads to injuries that just compound the problem of being lost.”

5. Succumb to summit fever:╠ř“This is actually a cultural problem,” says Daryl Miller, lead climbing ranger at Denali National Park. “The first question everyone, climbers and non-climbers alike, asks after a trip is, 'Did you summit?' Not, 'Did you enjoy the journey?' Weather and other hazards aren't the real problem, they only compound problems that begin with bad decisions that start with pushing for the top.”

6. Enter a cave without the right equipment:╠ř“We have a name for the people who go caving with inappropriate safety gear, clothing, no backup light, and inappropriate footwear: We call them 'flashlight cavers,'” says Art Fortini of the National Cave Rescue Commission. “Falls, more than getting lost, are typically the leading cause of injury. In many cases, simply having both hands free and using proper footwear can prevent trouble.”

7. Don't tell a responsible person where you're going:╠ř“This may be one of the simplest precautions you can take,” says Fortini. “But for some reason, it's the one thing people often neglect or forget to do.”

8. Move too quickly:╠ř“When people discover they're lost, their biggest mistake often happens within the first 15 minutes,” says Shimanski. “That's why I have a general rule that if you're ever lost, you should STOP: Sit. Think. Observe. Plan.”

ÔÇöNick Heil

Uncle SAR Wants You

While a handful of full-time search-and- rescue jobs exist, roughly 95 percent of all SAR personnel are volunteers. Jonesing to join the ranks, either as a volunteer or a professional? Contact your county sheriff or state police for info on local SAR groups. Or get in touch with the umbrella agencies below, which can help whether you're looking to lend a hand or fancying a career with a national organization.

:╠řProvides instruction materials, standardized tests, and accreditation programs for local SAR teams, plus education in all aspects of mountain safety. Also offers SAR contact info for 90 units in the U.S. and Canada on its website.

:╠řOffers training in everything from treating hypothermia to technical rope skills. Also has information on certification for SAR dogs.

:╠řHolds cave-rescue training seminars for cavers with all levels of experience and provides contact info for local cave SAR groups around the country. Also call the .

:╠řOffers full-time and volunteer ranger positions in parks and monuments nationwide; SAR training programs are not offered through the NPS.

:╠řProvides contact information for tracking groups nationwide.

:╠řOffers full- and part-time positions. Provides training nationwide in maritime safety and rescue operations.┬á

and :╠řOffer information and training for aspiring EMTs and Wilderness First Responders.┬á

ÔÇöKi Bassett

Lost and Found: Reports from the Field

Burning ropes, 400-foot free falls, illicit drug use, and other scary (but true!) tales (and barroom-worthy scuttlebutt) from the veterans who were there.

Star Search:╠řWhen an early-September blizzard left five climbers missing on Wyoming's 13,770-foot Grand Teton, park rangers Renny Jackson and James “Woody” Woodmencey slogged up 5,000 feet, breaking trail in knee-deep snowdrifts. They reached the Lower Saddle at 11,600 feet, and, faced with 100 mph gusts, they settled into a crude hut, certain that the next morning's mission would be a body recovery. That is, until Woodmencey stepped outside to shine a beacon for a second team of rescuers who were scheduled to meet them at the saddle. Glancing upward, he thought he saw a star above the peak. “Being a meteorologist,” quips Jackson, “Woody determined it was not where a star should be. He flashed his light up, and got a blinking response.”

After the other team arrived, with high winds still pummeling the mountain, the rangers crossed into the icy Wall Street Couloir, where they established voice contact with one of the climbers. By that time, another victim had already skidded over the edge and died far below, and as the rangers moved upward, they unknowingly passed two corpses lying in hypothermic repose. The rescuers discovered Paul Johnson perched on a cliff band and Greg Findley, who'd shined the headlamp, 165 feet below him. They raised Findley to the cliff band and all six spent the night there before descending on ice-covered ropes to the Lower Saddle, where a helicopter picked them up. “I was worried about Findley,” says Jackson. “But he was doing OK for a guy who was encrusted in snow and ice.”┬áÔÇöRob Story

The Lazarus Principle:╠ř“Our team once spent six days looking for a 69-year-old woman on Mount of the Holy Cross, Colorado. She'd gotten separated from her group and while she was moving through a boulder field, she'd slipped and fallen 70 feet. The temperature dropped into the twenties each night, and after six days the rescue squad assumed the worst. I told the sheriff to cancel the search, and I was walking toward the briefing room to tell the woman's family that she was gone when I got a call: The last helicopter searcher had seen a flash of color on the mountainside. The semiconscious woman rolled over at the exact moment that the helicopter flew past, and her arm dropped from behind a boulder and into the open, so that the red sleeve of her parka was visible. We'd been over that area three or four times, had search dogs within 50 feet of her, and we'd never had any indication of her. Now I never give up on searches.” ÔÇöTim Cochrane, Vail Mountain Rescue Group

Murphy's Lawyers:╠řOne morning, while hanging out in his Yosemite Valley cabin, ranger Butch Farabee heard two people screaming for help in the mountains above. A climber had fallen while rapelling on Glacier Point ApronÔÇöa 300-foot 5.6 route on the south side of the ValleyÔÇöand was now stuck (one broken collarbone later) with his girlfriend on a ledge the size of a kitchen table. After spotting the two with his telescopeÔÇöwhich “was strong enough that you could read someone's underwear label from a mile away”ÔÇöFarabee teamed up with Yosemite climbing legend Ron Kauk. The pair was lowered by helicopter to the Apron; then they rappelled down to the climbers. Says Farabee, “I was strapping up the guy's shoulder when we got a radio call: 'Do you know there's a fire above you?'” The victims hadn't put out the fire from their bivy the night before and the helicopter had stirred up the embers. Farabee worried that the safety ropes were in danger of burning. The helicopter returned to attempt a longline rescue, but it was too windy for the pilot to get close enough to them without driving a rotor blade into the cliff. Farabee and Kauk had no choice but to jumar up the route to the ledge below the fire and haul up the victims, moving quickly before the fire got out of control. They made it to the top of the Apron and were flown down to Yosemite Valley. “There were 300 people there clapping for us,” says Farabee, “which, of course, is a great way to end a rescue.”┬á

Granny on the Lam:╠ř“I once tracked a woman in Joshua Tree. She'd started hiking with her grown grandchildren, gotten tired, and turned around. But when her family returned to the campground, she wasn't there. From her point last seen, I cut for signs and eventually found the place where she veered off the trail. By examining her footprints, I could see where she stopped and adjusted her stance, where she looked at a barrel cactus that'd been busted by bighorn sheep, and where she watched a phainopepla bird eat mistletoe berries. I began calling her Grandma. It's good for a tracker to establish a cognitive closeness to the subject. I could tell within a few paces where she was lost: Her prints became frantic. I saw where she sat down and drummed her fingers on the ground. I could clearly see her confidence level eroding. She'd forgotten she'd crossed into another canyon instead of turning back. Several hours later, I got a radio call that she'd found the road and had hitched to the visitor center. She was fine, despite doing the very worst thing for a lost person to do: keep moving. We'd intimately shared a path for a few hours, yet never met.” ÔÇöHannah Nyala, former National Park Service Tracker

Joint Task Force:╠ř“Back in the early 1970s, hikers in Yosemite found a skull of a guy who'd disappeared in '66. He'd worked at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, and there was a theory that he'd been killed because he had top nuclear secrets. After the skull was discovered, his wife said, 'If you find anything more, please bury it there.' Several months later, a hiker found a knuckle. He was a hippie, and this was when drugs were rampant in Yosemite. He took me to the knuckle, and we soon uncovered about half the bones. We buried what we could, made a small stone cross, and then went down to the river to clean up. The hippie pulled out a bag of weed and asked, 'Do you mind if I toke up?' I was a ranger and a former highway patrolman, but this guy had just helped me bury bones. So I said, 'Today's a freebie. But if I see you smoking tomorrow, I'm gonna take you to jail.' He said OK, and lit up.” ÔÇöButch Farabee, retired Yosemite climbing ranger

Drag Race:╠ř“Cave rescues don't happen that often, but when they do, the logistics are daunting. Radios don't work, so you have to send notes on paper with runners; helicopters are meaningless; hypothermia is always a concern; and routes are often too narrow to get a stretcher in. In 1995, I was part of a rescue in Lechuguilla, a cave that drops 1,567 feet below the New Mexico desert. One of the dozen people in the cave slipped and broke a rib 800 feet down. There were several rope climbs between him and the exit; he attempted the longestÔÇö150 feetÔÇöbut got stranded halfway up in intense pain, unable to go up or go down. When I lowered him back down to the pit he was like an inert sack of potatoes, too weak to do anything, so another rescuer and I formed a new plan. He assembled a team at the top of the pit where they'd be needed, while I left to get backup equipment. A few hours later we were back at the cave with full battle regalia. We used hundreds of feet of rope, made pulleys to set up a mechanical advantage system to lift his jury-rigged litterÔÇöbasically a glorified drag chute of thick polyethylene that wrapped around himÔÇöand set anchors at the top of the 150-foot drop and at three other, smaller drops. Fatigue was the toughest factor. People got hungry, they wanted to sleep, they needed Ziploc bags to shit in and bottles to pee in. From the time we got him off the first rope till we got him out took 17 hours.” ÔÇöArt Fortini, National Cave Rescue Commission

No Batteries Required:╠řOn May 17, 1960, one hour after summiting Mount McKinley, John Day, Pete Schoening, and Jim and Lou Whittaker took a savage 400-foot tumble down the icy West Buttress. The fall snapped one of Day's ankles and shredded the ligaments of the other, and Schoening suffered a bad concussion. Jim Whittaker found Schoening dazed and missing a glove, dangling over a 3,000-foot cliff. They were 17,200 feet up McKinley, in temperatures approaching zero degrees.

Ten days later, with Day's toes going black and their precarious position preventing the more than 65 rescuers on the mountain from reaching them, local heli pilot Link Luckett managed to fly his two-seat Hiller up to 17,200 feetÔÇöafter jettisoning the battery and removing the right-side door. When he landed on the buttress, he yelled to the Whittakers, “Don't put John in yet! I wanna see if I can take off without crashing. I'll be back.” He kept his word, but with Day on board the chopper barely generated enough lift to propel it to the edge of the glacier. “They disappeared over the ice, and we thought they might have crashed,” recalls Jim. “But they didn't.” A few hours later, Luckett came back and retrieved Schoening. The Whittakers descended 2,000 feet to the rescuers' base camp on their own.