I’ve been working up here for 11 years. We used to have the world-record wind speed, 231 mph, back in 1934. Then a . We still have the highest in North America. Right now, it’s a balmy minus 5 degrees, and the winds are only 40 mph. It’s not a bad day.

We’ve seen snow up here every month of the year. We’ve had winds over 100 mph every month of the year. We can get gnarly weather even in summer. It’s not a tranquil place.

We work eight days on and six days off. When we’re working, we live here. We ride a snowcat up here. That takes an hour and a half to eight hours, depending on visibility. Sometimes we turn around.

I work the night shift, from 5:30 p.m. to 5:30 a.m. Every hour, we go out to read the instruments. Then we send that data to the National Weather Service, and we make forecasts. Working nights has its challenges: I work alone. You have to watch your step. You don’t want to slip and knock yourself out.

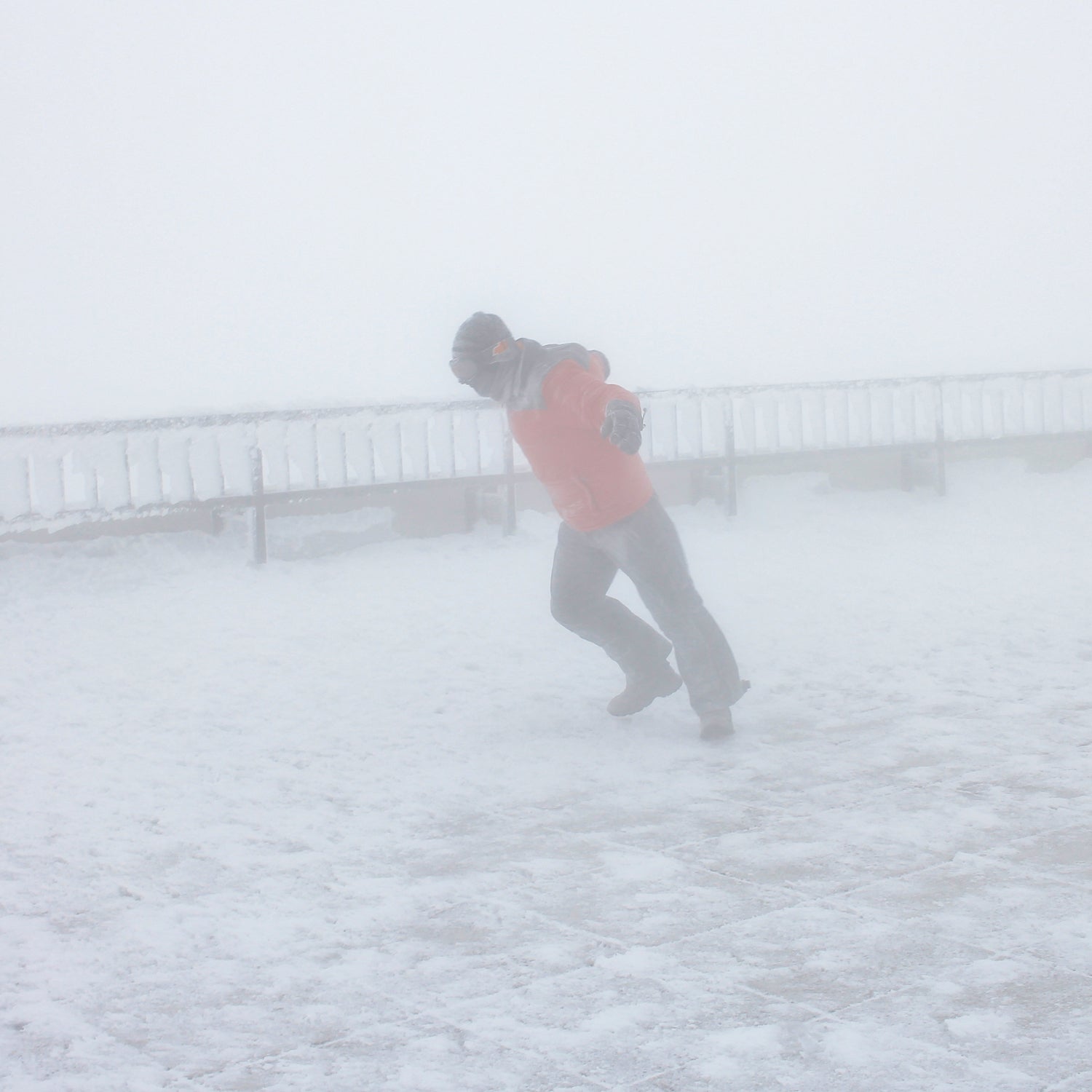

We wear rated to minus 40, sometimes with three pairs of wool socks. We wear two or three insulating leggings below a good pair of . We wear three top layers and a down jacket with a windproof shell. We use two or three balaclavas to make sure no skin is exposed on our face, and then a good pair of goggles. We usually wear two pairs of gloves. We definitely suit up. Tonight will drop to minus 30 with winds of 50 to 70 mph, which means exposed skin could see frostbite in five minutes.

���ϳԹ���, we measure temperature, visibility, cloud height, sky condition, precipitation, and ground condition. In winter, we have to climb our tower to de-ice the instruments. The tower is three stories high and gets a lot of rime ice from frozen fog, which looks pretty but clogs the instruments. Once an hour, we break off the ice. Rime ice comes off easily with the whack of a crowbar. Glaze ice, which is clear, takes longer.

The most extreme condition here is the wind. The highest I’ve experienced is 158 mph. I was up the tower, de-icing the instruments. I was relatively safe, but I could still feel the force. The closest thing to it is skydiving.

Most people can’t stand upright in wind above 112 mph. People worry it will pick them up like . But you’re leaning into it, so the first thing to go is your feet. You fall, and you slide. Rime ice is a frictionless barrier. Eventually gravity and friction slow you down. Then you have to get to safety. It’s like a riptide. Don’t go head-on into it—zigzag to the lee of a building. I’ve been knocked down several times, and I’ve slid a couple hundred feet. We call it the crawl of shame.

Up here, we’re not just looking at the weather on screens like other weather jobs. We’re getting out and feeling it. Some people go storm chasing, but here the storms come to us.

It feels like a lighthouse. When it’s undercast and we’re surrounded by clouds, we can look out and see two or three peaks poking up. It looks like the Hawaiian Islands in a sea of clouds.

Interviewed by Jacob Baynham.