Hear Bill Vaughn read an excerpt from this article on National Public Radio’s

THIS IS THE WAY WE DIE. Middle-aged men with martini bellies shoveling snow off a rink, or charging the net, or sprinting around some steamy track in July, trying to prove something. The bloated heart seizes, the stressed vessel explodes, and suddenly we’re pitched into the abyss, face flat against the ice, the clay, the cinders.

As I lurched into the final lap, the temperature pushing 95, it felt like some street-corner thug was thumping my solar plexus with his knuckles. You gotta problem, Peter Pan? You wanna cha-cha? But this yelling wasn’t coming from some unknown bully, it was coming from the bully I had married, my wife, Kitty. “Run faster!” she shouted as she ran behind me, checking her stopwatch, totally not winded. “What’s wrong with you?”

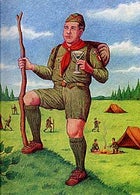

With 100 yards left to go, the pain in my chest moved an octave higher, and my hamstrings began to screech. It was Independence Day, the final day I had allowed myself to attempt a seven-minute mile and reach out at last to grab my dream—the Eagle badge, the highest rank a Boy Scout can earn. If I could somehow stumble across the finish line, at least I could bite the dust in the service of a cause. I could picture it, the heroic plaque bearing my name at the national headquarters of the Boy Scouts of America in Irving, Texas. This Bird Soared, it would say, Better Late Than Never. A year earlier, when I happened upon a copy of what had been the most influential book of my boyhood, misfiled on a shelf of used novels in one of those dusty bookstores that smells of cats, I got the sort of spiritual jolt Christians must experience when they see the Shroud of Turin. Ah, there he was again, unremembered for 40 years: Norman Rockwell’s red-haired, freckle-faced geek in gaiters and a full field uniform, striding across a piney ridge, grinning that infectious grin, one hand raised in good cheer, the other one clutching the 1959 edition of The Boy Scout Handbook.

Rockwell’s portrait of Howdy Doody in khaki would be the first of the many delicious mysteries Scouting would throw my way. In the painting, the Handbook that Howdy Doody is clutching bears a painting of Howdy clutching a Handbook, which also bears a picture of Howdy clutching a Handbook…and so on. I squandered many hours with a magnifying glass and a microscope probing this hall of mirrors to see if it was infinite, one of the reasons my progress through Scouting’s ranks was retarded.

And while other Scouts were rising from Tenderfoot to First Class and Star and Life, or even to the coveted Eagle, I got bogged down in such arcane fixations as the Ner Tamid, a blue-and-white ribbon suspending in bronze the Ark and Eternal Light of the Jewish faith. Not only was I not Jewish, I believed that the “rabbi” you were supposed to consult in pursuit of this beautiful and mysterious religious icon was actually a hutch of rabbits you worshiped, a sort of 4-H project with spiritual overtones.

But for me, then a skinny and vastly ignorant 11-year-old growing up in the boondocks of central Montana, the most intriguing passage in the handbook was titled “From Boy to Man.” Although unencumbered by any explanation of reproduction, here was the first mention I’d ever seen of a phenomenon called nocturnal emissions. It came with an ominous warning, however, resonant of The Mummy’s Curse: “There are boys who do not let nature have its own way with them but cause emissions themselves. This may do no physical harm, but may cause them to worry.” Worry about what, I wondered. And how could you cause such emissions yourself, whatever “emissions” were? Most important, why would you want to?

By the end of my Scouting days at age 13, I managed to advance only to First Class, earning a paltry five merit badges along the way, 16 short of the 21 mandatory and optional badges required for Eagles. Now, standing in the bookstore thumbing through this scuffed and dog-eared handbook, which had belonged to some careless runt named Steve, I inhaled deeply its faint perfume of pine smoke and mildew, and there lifted from my spirit a great rancid aura of regret. I suddenly knew what I wanted. I wanted to finish my career as a Boy Scout. I wanted to be an Eagle.

I DROPPED BY THE office of a poker buddy, a crime attorney we call Loophole, who donates his spare time to a Missoula troop that meets at St. Francis Xavier Church. I was looking for a scoutmaster who would sponsor my rise to the top.

“You want to get involved again, and that’s great,” he said. “So why don’t you just sign up to be a volunteer?”

“Yeah, I probably will,” I lied. “But I want to do this first. So I have more, you know, standing?”

Loophole leaned back in his executive leather chair and arranged his features into the poker face that made him such a shark at our weekly games.

“No can do.”

“What do you mean?”

“There’s a rule. If you don’t get the Eagle by your 18th birthday you can’t ever get it.”

Since Loophole is a lawyer, I didn’t believe him. So I wrote a letter to the Boy Scouts of America. The response was a note from John P. Dalrymple, the director of the National Eagle Scout Association at the time, who confirmed that unbending policy. “We receive a number of requests each year from adults who would like to go back and complete the requirements,” he wrote. “Most had attained the rank of Life Scout and only needed one or two merit badges.”

I decided to forge ahead without the blessings of the BSA. Because I would lack official endorsement, I couldn’t even pursue the Eagle as a Lone Scout, a program for kids living in backwaters like mine. I’d have to do my work as a Virtual Scout. I would enlist Virtual Counselors to oversee my efforts and sign my own forms when I met the requirements. Since I planned to follow the Scouting guidelines used in my day, I returned to that smelly bookstore to search for merit-badge pamphlets from the early 1960s.

While chasing down this vintage literature, I learned that shifting demographics have forced Scouting, like all American institutions, to adapt. When the BSA began losing membership in the 1970s its leaders realized that they needed to cast a wider net, to the burgeoning horde of urban boys whose opportunities to experience the outdoors were limited, for instance. The heart of Scouting is still swimming, fitness, camping, and hiking—the whole summer-camp routine, albeit these days it’s a good deal less demanding of brawn than of brain. To become an Eagle now you must count among your 21 merit badges Communications, Emergency Preparedness, and Environmental Science. No longer are badges offered for Cotton Farming, Small Grains, or Beekeeping, but you can earn optional badges in Cinematography, Crime Prevention, or Truck Transportation. There’s one for Disabilities Awareness. And one for Genealogy, a nod to the Mormons, who command such a central role in Scouting today that their threat to withdraw 400,000 Scouts from the movement may have been a deciding factor in the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the BSA’s ban on homosexual leaders.

I set about recruiting my Virtual Counselors, and I pleaded with Kitty to serve as my Virtual Scoutmaster.

Her eyes narrowed. “What’s in it for me?”

After a good deal of whining, I finally swung the deal by agreeing to a deadline: If I didn’t earn the 16 merit badges I still needed in one year, by the end of business on July 4, I’d give up. I wasn’t worried. True, fewer than 4 percent of all Scouts ever become Eagles. But these tests were designed to challenge the intellectual and physical prowess of an adolescent. How hard could they be?

EIGHTEEN MILES into the big trek—the 20-mile slog that caps the requirements for the Hiking badge—the November rain turned to sleet. My left Achilles had announced a mile earlier that it was working under protest, and if I ever wanted to play tennis again I better cease this nonsense pronto. Even more irksome was the camp smoke rising up ahead in the gathering dusk. Although the route I had mapped out leads into an industrial wasteland surrounding the train yards of Missoula, I figured that in the chill of early winter the hobo jungles here would be deserted.

“Best set yerself,” a voice called out.

He could have been 20, or 60. He had Charlie Manson eyes, hair so matted it had gone to dreadlocks, and the tip of his nose was missing. But the scavenged plywood nailed above him in a clump of haggard cottonwoods was keeping off the weather, and there was a dry lawn chair next to his fire. In my exhausted state it looked like a throne.

“Where you headed?” he asked. If this guy was a bludgeon killer he was certainly pleasant about it.

“Downtown,” I groaned in relief as I sat down, imagining again the cheeseburgers and beer that were waiting for me at my favorite grill, if I could just get there.

“You don’t want to go down there. They got a new loiter law, and you can’t panhandle no more neither.”

I rubbed at the cramp building in my calf and wondered why this hike was causing me such grief. After all, I had polished off with relative ease the five ten-milers also required for the badge. For one of these marches I went on a tour of Kota Kinabalu, the sultry and buggy capital of Malaysia’s Sabah province, carved from rainforest on the north coast of Borneo. On another, I trudged along the Ptarmigan Wall in Glacier National Park, annoying other hikers by singing “I Love to Go A-Wandering.”

After I finished with this litany the man looked at me hard, then reached into a brown plastic garbage bag under his chair. I flinched, thinking that he was going to brandish a tire iron after all. But what he held out was a pint of Lewis & Clark vodka. I took a pull on it.

“I was a Scout,” he said.

This was news that simply clobbered me. By the looks of his rummy eyes the only merit badge he’d ever earned was for Distilling.

“Yeah, had my Star badge.”

I braced for some heart-wrenching tragedy. “What happened?”

He took a hit from the bottle and screwed the cap back on. “Got more interested in 4-H. The steers. And whatnot.”

WHEN I WAS 11, I JOINED the Legions of Pottsylvania, a gang of kids named after the Balkan-style homeland of Boris and Natasha in the animated Rocky and Bullwinkle television show. I eventually rose to the top through seniority and dumb luck displayed during dirt-clod wars with other gangs, and thus became Pottsylvania’s general. But under the autocratic rule of the new supreme commander, defections increased. Finally, Arthur Lemon, my trusted aide-de-camp, announced that he would no longer have any time for Pottsylvania either; he’d joined the Boy Scouts. He was wearing a khaki uniform with a black scarf tied around his neck in a dapper, squared-away manner. There were official insignia sewn to his shoulders, and on his chest flashed a shiny piece of bronze. This was so far beyond our puny efforts to cast Pottsylvania in a military mold that I was instantly smitten with envy.

“You should join,” he said. “I’m gonna ride up there right now.”

“Up there” was a sprawling house on a bluff above the Missouri River owned by a heart surgeon. When David, the surgeon’s son, announced that he wanted to be a Scout, the good doctor decided that rather than ferry the kid into town he’d bring the Scouts to David. So they organized a unit they called the Skull Patrol, and designed a scarf featuring a phosphorescent skull-and-crossbones on a field of black silk.

“So who’s this, Arthur?” The intense block of a man who was shaking my hand spoke like Orson Welles and looked like Jimmy Cagney. He smelled of pipe smoke and horses and bay leaf, and emanated such confidence and goodwill that whatever it was the Boy Scouts were all about, I knew I just had to be part of it.

The following summer the sun sparkled on the impossibly blue waters of Lower Saint Mary Lake on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation just outside Glacier Park, causing the Second Class badge on the chest of my new uniform to flash agreeably. I was kneeling in the stern of a canoe working on the J-strokes you must perform in order to qualify for the Canoeing merit badge. The final test would be the next morning at dawn. I would be asked to name the parts of the canoe, show the counselor all the strokes, and, finally, overturn my boat in these bone-numbing waters and prove that I knew how to right the craft and slosh the water out of it in the single deft move all the candidates had been taught. (Canoeing turned out to be one of the few skills I would ever master.) In the bow, David had turned around to coach me, and to recite an inspirational limerick from the stores of doggerel he had committed to memory. There was a young woman from Kent…

After David’s father abandoned the Skull Patrol and ran off to California with his nurse, I was surprised when my old man caved in to my pleas to serve as our scoutmaster. You’d think my badges would have flowed like wine, but when I went to him for the Painting badge after a bit of labor on our picket fence, he told me that if I wanted it bad enough I’d have to do the house. To this day the smell of paint makes me gag. Also. the color turquoise.

IN A CLEARING NEXT TO Little Back Creek, a streamlet that issues through the riverside half of the western Montana ranchette that Kitty and I call home, I piled brush around the bowed trunk of a massive cottonwood that had keeled over from old age. I built a nest inside this humpback from dead leaves and bunchgrass, and a fire ring outside it from river rocks. My cozy debris shelter would be the headquarters of my battle to prove to Kitty that I deserved the Camping, Cooking, and Nature merit badges. There would be no Gore-Tex tent for me, ma’am, no $300 sleeping systems or propane stoves. For two days I would eat trout from the river and morel mushrooms from the swamps washed down with tea brewed from chamomile I picked myself.

I intended to overachieve in these matters because my struggles with Scouting the past 11 months had surprised and humbled me. Yes, I had qualified fair and square for the dozen merit badges I had tackled so far, but in some cases just barely. Dog Care, for example, administered by our veterinarian. When I was asked to put our red heeler through his paces, Radish crawled under the horse trailer after I ordered him to stay, barked when I told him to sit, and peed on the vet’s truck when I threw a stick for the beast to fetch.

“I’m going to pass you,” the vet said. “But only because you did good on the knowledge part. Maybe you should think about obedience school.”

The pursuit of some other badges had been protracted sieges. My essays about the natural history of our ranchette and the role of forests in the economy ran several thousand words. I sent this complicated project to one of my Virtual Counselors, a forester who happens to be my brother-in-law, and who caretakes a private estate in New Hampshire. He picked it to pieces, scolding me for losing my objectivity about corporate loggers and their running-dog lackeys in the Forest Service. But in the end he gave me my badge.

It took me two warm-weather seasons to complete Lifesaving, partly because I’m a clumsy and inept swimmer who relies almost exclusively on the dog paddle and the backstroke, but mostly because whenever I dove into our lagoon, where I was practicing to save Kitty from “drowning,” water shot up my nose. The Horsemanship badge was relatively easy because I’ve ridden my whole life, and it was Kitty who trained Timer, my mare. But the counselor was my sister-in-law, a barrel racer from Kansas whose rodeo triumphs are family legends. Wilting under her critical glare I blanked on the names of the muscles and bones of the equine hindquarters. Even though my riding test came during a winter freeze, when she finally let me off Timer I was bathed in a nervous sweat.

When it came time to take the test for the Firemanship badge, the counselor I wanted didn’t want anything to do with me. Not only was he a real fireman, he’d been an Eagle himself, and was deeply suspicious of journalists because of widespread criticism of the BSA’s stand on homosexuality.

“I’m not interested in that story,” I tried to reassure him. “I’m only interested in me.”

“Look,” I pushed on, “why would I care? When I was a Scout there weren’t any homosexuals.”

After he turned me down I considered trying to recruit someone from our rural firehouse, but all those guys had been in the crew that had doused a blaze I had caused in our kitchen a year earlier by leaving a pan of cooking oil unattended on the stove. So in the end I had to turn to Kitty to stand in as my counselor.

ON MY SECOND afternoon at camp I waded into the river and cast forth a length of fishing line baited with a newly hatched salmon fry. Kitty had signed off on my Camping and Nature badges, but it was crucial now that I catch a fish. My test for Cooking was scheduled for dinner, and I had nothing to cook except a few morels and a handful of rice. But the fish weren’t biting, and by 5 p.m. I was panicked. Then an old man wandered down the beach from his boat and I learned that the river had been generous to at least one angler that afternoon.

Later, as a great horned owl hooted nearby in the glow of sunset, I poured Kitty another beer and put a stick on the fire. “How’s your trout?” I asked.

“It’s very good,” she said. “What did you catch them on?”

“Oh, this and that. Whatever.”

“No, really.”

“A Jackson,” I mumbled. “And a Hamilton.”

She put down her fork. “You bought these fish?”

“The requirements say to cook camp food. It doesn’t say how to get it.”

We sat in silence for a moment. “So are you going to be able to finish Personal Fitness?” I shrugged. “I don’t know.”

With a month to go it was the only test I had left, but it was proving to be the hardest. When I was rummaging for merit-badge pamphlets I could only find a few editions from the 1960s, forcing me to abide by the contemporary requirements for most of my badges. Unfortunately, I happened to find the 1960 printing for Personal Fitness, which then, as now, is a mandatory badge. But while the modern requirements ask nothing more of a boy than as many sit-ups, pull-ups and push-ups he can do in 60 seconds, the old rules demand that you perform 50 sit-ups, eight pull-ups, and 21 push-ups.

Sir, yes, sir! I managed to finish these tasks in relatively short order, even excelling in the sit-up department by knocking out 100. But while the wussified contemporary badge asks you to write an essay about why tobacco is bad and why you should eat good food, the old rules order you to swim 100 yards, perform an 18-inch standing jump, and run a seven-minute mile. I bought a club-quality treadmill and trained all winter while watching reruns of Rocky and Bullwinkle. I gradually moved from a 12-minute mile to a nine-minute one, and I surprised myself in April by clocking in at 7:16, although I had to grab onto the treadmill’s arms for dear life. But I despaired of ever being able to do better. I told myself that maybe when summer came the sun on my face and the wind in my hair would inspire me, and my little black heart would find the strength it needed to push me home.

SIX MONTHS AFTER my Eagle deadline had passed, the woods were glowing with Yuletide cheer as we gathered around the family’s annual Christmas bonfire for fireworks, singing, and speeches about everyone’s achievements during the year. I was glowing as well, and not just because of the industrial-strength martini I’d served myself at dinner. In the circle were a number of my Virtual Counselors, and they were glowing too. Kitty read the speech I had prepared for her, in which she lauded my true grit and welcomed a new Eagle into the world. And then she surprised me by pinning a tiny gold eagle earring to the chest of my crisp new Boy Scout khakis. Instead of carols this year, I suggested, how about we do a few camp songs instead? After handing around some sheet music I’d copied from the 1963 Boy Scout Songbook, I led a lackluster rendition of “Home on the Range,” and then “Red River Valley.” Halfway through “Waltzing Matilda” slackers began to drift back to the house for a card game. As Kitty left I told her I would stay till the fire burned down. When everyone was gone I opened the songbook and squinted at the words. Except for the baying of a neighbor’s hound, the woods were silent. Under the constellations I sang “Scout Vesper,” to the tune of “O Tannenbaum.”

Softly falls the light of day,

While our campfire fades away…

Have I done and have I dared,

Everything to be prepared?