How 1,600 People Went Missing from Our Public Lands Without a Trace

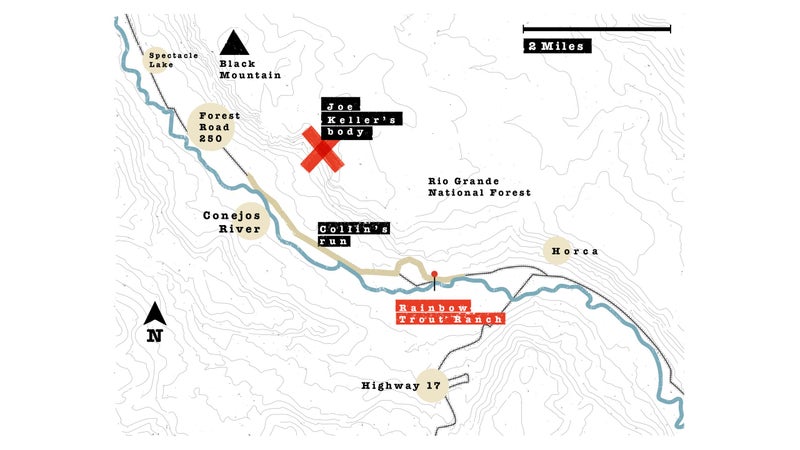

When 18-year-old Joe Keller vanished from a dude ranch in Colorado's Rio Grande National Forest, he joined the ranks of those missing on public land. No official tally exists, but their numbers are growing. And when an initial search turns up nothing, who'll keep looking?

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

July 23, 2015 was the eve of Joseph Lloyd Keller’s 19th birthday. The Cleveland, Tennessee, native had been spending the summer between his freshman and sophomore years at Cleveland State Community College on a western road trip with buddies Collin Gwaltney and Christian Fetzner in Gwaltneyâs old Subaru. The boys had seen Las Vegas, San Francisco, and the Grand Canyon before heading to Joeâs aunt and uncleâs dude ranch, the , in the San Juan Mountains in southwestern Colorado.

The ranch is in Conejos County, which is bigger than Rhode Island, with 8,000 residents and no stoplights. Sheep graze in the sunshine; potatoes and barley are grown here and trucked north to Denver. Three new marijuana dispensaries in the tiny town of Antonito lure New Mexicans across the nearby state line.

ConejosâSpanish for ârabbitsââis one of the poorest counties in Colorado. Itâs also a helluva place to get lost. While its eastern plains stretch across the agricultural San Luis Valley, its western third rises into the 1.8-million-acre Rio Grande National Forest, which sprawls over parts of nine counties. Go missing out here and your fate relies, in no small part, on which of those nine counties you were in when you disappeared.

Joe, a competitive runner, open-Âwater swimmer, and obstacle-course racer, and Collin, a member of the varsity cross-Âcountry team at Division I Tennessee Tech, had been running together often during their trip. Neither was totally acclimatized to the altitudeâthe ranch sits just below 9,000 feet. Joe was a bit slower than his friend. He suffered from asthma as a three-year-old but had kicked it by age 12. The workout would be routine: an hourlong run, likely along Forest Road 250, which bisects the ranch and continues into the national forest, following the Conejos River upstream.

Joe left his phone and wallet at the ranch house. He wore only red running shorts, blue trail shoes, and an Ironman watch. Shirtless, with blond anime hair and ripped muscles, he looked more like a California lifeguard than a Tennessee farm kid.

4:30 p.m. The friends started out toÂgether. Neither runner knew the area, but old-timers will tell you that even a blind man could find his way out of Conejos Canyon: on the south side, runnerâs left, cattle graze in open meadows along the river. On the north side, Âponderosa pines birthday-Âcandle the steep tuff until they hit sheer basalt cliffs, a massive canyon wall rising 2,000 feet above the gravel road toward 11,210-foot .

As the two young men jogged by the corral, one of the female wranglers yelled, âPick it up!â They smiled and Joe sprinted up the road before the two settled into their respective paces, with Collin surging ahead.

The GPS track on Collinâs watch shows him turning right off Forest Road 250 onto the ranch drive and snaking up behind the lodge, trying to check out three geologic outcroppingsâFaith, Hope, and Charityâthat loom over the ranch. But the run became a scramble, so he cut back down toward the road and headed upriver. A fly-fisherman says he saw Collin 2.5 miles up the road but not Joe. Collin never encountered his friend; he timed out his run at a pace that led to puking due to the altitude.

No Joe. Collin moseyed back to the ranch house and waited. An hour later, he started to worry.

The search engaged about 15 dogs and 200 people on foot, horseback, and ATV. An infrared-equipped airplane flew over the area. A $10,000 reward was posted for information. How far could a shirtless kid in running shoes get?

When Joe didnât show up to get ready for dinner, Collin and Christian drove up the road, honking and waiting for Joe to come limping toward the road like a lost steer. At 7:30, a small patrol of ranch hands hiked up the rocks toward Faith, the closest formation. By 9:30 there were 35 people out looking. âIf he was hurt, he would have heard us,â recalled Joeâs uncle, David Van Berkum, 47. âHe was either not conscious or not there.â

âThe first 24 hours are key,â says Robert Koester, a.k.a. Professor Rescue, author of the search and rescue guidebook . Koester was consulted on the Keller case and noted that, like most missing runners, Joe wasnât dressed for a night outside. Plus, he says, it wouldnât have been unusual for a young athlete like Joe to switch from run to scramble mode. âHeading for higher ground is a known strategy for a lost person,â he says. âMaybe you can get a better vista. And based on his age, it might just have been a fun thing to do.â

Around 10 p.m., the Van Berkums called the Conejos County Sheriffâs Department, and sheriff Howard Galvez and two deputies showed up around midnight. It was now Joeâs birthday. At this point, the effort was still what pros call a hasty searchâquick and dirty, focusing on the most logical areas.

It was a warm night, and everyone still expected Joe to find his way back at daybreak, wild story in tow. That morning, as ranch employees and guests continued the search, Jane Van Berkum, 48, alerted Joeâs parentsâZoe, 56, and Neal, 59. Zoe and Jane are sisters, originally from Kenya; their family, British expats, left the country in the 1970s. It took the Kellers and their 17-year-old daughter, Hannah, less than 24 hours to get to the ranch from Tennessee, flying into Albuquerque, New Mexico, and renting a car for the three-and-a-half-hour drive north.

The family arrived at 2 a.m. In the morning, at 6 a.m., the professional search began: starting at what searchers call the point last seen, the ranchâs big ponderosa pine gate, a deputy fire chief from La Plata County named Roy Vreeland, 64, and his Belgian malinois scent dog, Cayenne, picked up a direction of Âtravel, which pointed up Forest Road 250. More dogs arrived from Albuquerqueâand identified different directions of travel or none at all. Additional firefighters drove over from La Plata ÂCounty. Everyone on the groundâas is largely the case with search and rescueâwere volunteers.

There was nothing to go on. In that first week, the search engaged about 15 dogs and 200 people on foot, horseback, and ATV. An infrared-equipped airplane from the flew over the area. Collinâs brother Tanner set up a GoFundMe site that paid for a helicopter to search for five hours, and a volunteer flew his fixed-wing aircraft in the canyon multiple times. A guy with a drone buzzed the steep embankments along Highway 17, the closest paved road, and the rock formation Faith, which has a cross on top. A $10,000 reward was posted for information. How far could a shirtless kid in running shoes get?

But after several days, volunteers began going home, pulled by other obligations. The few who remained did interviews, followed up on leads, and worked teams and dogs. But the search was already winding down. âWe had a very limÂited number of people,â one volunteer told me. âThatâs fairly typical in Colorado. You put out calls and people say, âWell, if he hasnât been found in that time, I have to go to work.â â

The absence of clues left a vacuum that quickly filled with anger, resentment, false hopes, and conspiracy theories. A tourist with a time-stamped receipt from a little gift shop in nearby Horca swore she saw two men on the road but later changed her story. A psychic reached out on Facebook to report a vision that Joe was west of Sedona, Arizona. There was even a theory that heâd been kidnapped in order to have his organs harvested and sold on the black market. âWe feel like heâs not in that area, heâs been taken from there,â Neal Keller would tell me months later.

âIâm a scientist,â Koester says. âIâm fond of Occamâs razor.â Thatâs the principle that the simplest explanation usually holds true. âYou could have a band of terrorists tie him to a tree and interrogate him. Is it possible? Yes. Is it likely? No.â

Joe Keller had just joined the foggy stratum of the hundreds or maybe thousands of people whoâve gone missing on our federal public lands. Thing is, nobody knows how many. The National Institute of Justice, the research arm of the Department of Justice, calls unidentified remains and missing persons âthe nationâs silent mass disaster,â estimating that on any given day there are between 80,000 and 90,000 people acÂtively listed with law enforcement as missing. The majority of those, of course, disappear in populated areas.

What I wanted to know was how many people are missing in our wild places, the roughly 640 million acres of federal landsâincluding national parks, national forests, and Bureau of Land Management propÂerty. Cases like 51-year-old , who, in 2013, vanished from a short petroglyph-viewing trail near the gift shop at Coloradoâs Mesa Verde National Park. , a 22-year-old rafting guide, who was wearing a professional-grade personal flotation device when he disappeared in 2015 in Grand Canyon National Park during a hike after setting up camp. Ohioan , who vanished from the PaÂcific Crest Trail last fall. At least two people have recently gone missing outside the national forest where I live in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. There are scores more stories like this.

The Department of the Interior knows how many wolves and grizzly bears roam its wildsâcanât it keep track of visitors who disappear? But the government does not actively aggregate such statistics. The Department of Justice keeps a database, the Â, but reporting missing persons is voluntary in all but ten states, and law-enforcement and coroner participation is voluntary as well. So a lot of the missing are also missing from the database.

After the September 11 Âattacks, InÂterior tried to build its own dataÂbase to track law-enforcement actions across lands managed by the National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Indian Affairs. (The Forest Service is under the Department of Agriculture.) The result, the ÂIncident Management Analysis and Reporting System, is a âlast year, only 14 percent of the several hundred reportable incidents were entered into it. The system is so flawed that Fish and Wildlife has said no thanks and refuses to use it.

That leaves the only estimates to civilians and conspiracy theorists. Aficionados of the vanished believe that at least 1,600 people, and perhaps many times that number, Âremain missing on public lands under circumstances that defy easy explanation.

Numbers aside, it matters tremenÂdously where you happen to disappear. If you vanish in a Âmunicipality, the local police department is likely to look for you. The police can obtain Âassistance from the county sheriff or, in other cases, state police or university law enforcement. If foul play is Âsuspected, your stateâs bureau of investigation can Âdecide to get involved. Atop that is the FBI. With the exception of the sheriff, however, these Âorganizations donât tend to go rifling through the woods unless your case turns into a criminal one.

But all those bets are off when you disappear in the wild. While big national parks like Yosemite operate almost as sovereign states, with their own crack search and rescue teams, go missing in most western states and, with the exception of New Mexico and Alaska, statutes that date back to the Old West stipulate that youâre now the responsibility of the county sheriff.

I thought that in the wild, someone would send in the National Guard, the Army Rangers, the A-Team, and that they wouldn’t rest until they found you. Now I’m not so sure.

âThere are no federal standards for terrestrial search and rescue,â Koester says. âVery few states have standards. A missing person is a local problem. Itâs a historical institution from when the sheriff was the only organized government.â And when it comes to the locals riding to your rescue, Koester says, âThereâs a vast spectrum of capability.â

Take : it has just one full-time law-Âenforcement officer, who wasnât given clearance to talk to șÚÁÏłÔčÏÍű. Ranger Andrea Jones of the 377,314-acre Conejos Peak district, where Joe disappeared, did lament to me that sometimes she discovers cases in the Âweekly newspaper. âOn occasions when we initially learn about a search and rescue in the forest from the Âlocal media,â she explained, âitâs difficult for us to properly engage, communicate, and offer available knowledge or resources.â

But wherever you are, once a search goes from rescue to recovery, most of those resources dry up.

On August 4, 2015, after Joe had been missing for 13 days, Sheriff Galvez pulled the plug on the official search. What had Âbegun as a barnyard musical was now a ghost story. The riverâalready dropping quicklyâhad been searched and ruled out. Dog teams had scratched up nothing. Abandoned Âcabins had been searched and searched again. âI mean, we checked the pit toilets at the Âcampgroundsâwe did everything,â Galvez said. âWe even collected bear crap. We still have it in the evidence freezer.â

Galvez had been elected sheriff only nine months earlier, and while he had years of law-Âenforcement experience, he had no background leading search and rescue operations. One responder told me that by the time he arrived on the second day of searching, tension was already rising between Keller and Sheriff Galvez. Keller felt that Galvez wasnât doing enough; Galvez felt that Keller was in the way, barking orders and criticizing his crew.

When dogs and volunteers start to go back to their lives and the aircraft return to the hangar, a missing-persons search can look eerily quiet. âFor a lost person, the response is limited to five days on average,â Keller told me. âThere needs to be a plan for applying resources for a little bit longer.â

The Keller family hired two private investigators, who turned up nothing. Zoe Keller told me that it was a waste of $800 a day; one of the investigators told me heâd never had a case with less to go on. The reward was raised from $10,000 to $25,000 and then to $50,000, but as David Van Berkum said, âThere just isnât a sniff of anything.â

Two weeks after Joeâs cold vanish, Alamosa County undersheriff Shawn Woods, who had been called in to assist by the ColoÂrado Bureau of Investigation, told Keller about a tracker he knew named Alan Duffy. A 71-year-old surgical assistant, Duffy became interested in bloodhounds when his 21-year-old brother, David, disappeared in the San Gabriel Mountains in 1978; he was found dead of gunshot wounds six weeks later. Duffy has since taken his dogs to search JonBenĂ©t Ramseyâs neighborhood and to track stolen horses in Wyoming. Calling in Duffy was a wild card, as are so many things in a case like this.

On August 15, Duffy loaded three-year-old R.C.ânamed after Royal Crown Cola, on account of his black and tan coatâinto his Jeep and drove 300 miles from Broomfield, Colorado, to the Rainbow Trout Ranch. A deputy gave him a scent item, one of Joeâs used sock liners. âThatâs as good as underwear,â Duffy said.

Duffy will tell you that bloodhounds are out of fashion. âThey fart and they drool,â he said. Theyâre susceptible to disease, they die young, and you canât let them off a lead Âunder any circumstances. âEverybody wants a shepherd,â he says. But going old-school has its advantages. âWhoâs gonna find you? Itâs not a shepherd. Itâs not a Mexican Chihuahua. Itâs not a pig. You know how they say a great white shark can smell a drop of blood in Âwater five miles away? Thatâs a bloodhound.â

R.C.âs trigger word to sniff for a living person, as opposed to human remains, is find. For search and rescue assignments, R.C. wears his orange harness, with Duffy holding the lead. After four hours of searching, Duffy switched R.C.âs harness to his black collar and told him, âWeâre gonna go gizmo,â the dogâs cue for cadaver mode.

Four and a half miles up Forest Road 250, at Spectacle Lakeâa murky pond, reallyâR.C. circled, tugged at vegetation on the bank, bit at the water, then jumped in and sat in the shallows. âHe wouldnât leave,â Duffy said.

Duffy wasnât convinced, necessarily, that a body was in the lake, and he explained that scent is drawn toward water and believed that there was a corpse somewhere nearby. Rain or critters could have deposÂited cadaver material in the lake, enough to set off alarms in R.C.âs snout. But at four and a half miles from Joeâs point last seen, the lake was at the far end of the ground gameâs probabilities. Duffy offered up a few more scenarios, some of which upset the Van Berkumsâsuch as when he told them that R.C. had picked up human-remains scents under buildings on the ranch. But with few other sources of help, desperation had led to Duffy. âAt least he was trying,â Joeâs mom, Zoe, told me. âHe could have been right.â

Continued searches in August turned up nothing. Neal Keller was commuting back and forth between Tennessee and Conejos County, searching every moment he could. In October 2015, when he and the sheriff were no longer on speaking terms, he urged the county commissioners for more help, including a dive team to search Spectacle Lake. âI, as the father of a missing boyâmy only son, actuallyâwould like to have as much resources as could possibly be made available,â he told the officials.

Keller was feeling the stress. He lost 15 pounds from hiking and scrambling in the altitude. Just before Thanksgiving, he, ÂDavid Van Berkum, and a small posse spent two days searching the snow-covered scree west of the ranch. It was the area that seemed most logical, but itâs mean terrain. âWe went in there because that area was likely the least searched,â he told me. No Joe. Keller would have to spend the long ColoÂrado winter still not knowing.

The canyon now belonged to the snowmobilers and coyotes. Next seasonâs fly-fishers and ranch guests wouldnât show up in any numbers until the snow melted in spring.

I first stepped through the missing-Âpersons portal back in 1997, when researching updates on Amy Wroe Bechtel, a runner whoâd vanished in the Wind River Range of Wyoming, where I lived.

My intrigue only grew. I tend toward insomnia and the analog, and each night in bed I listen with earbuds to Coast to Coast AM on a tiny radio. The program, which explores all sorts of mysteries of the paranormal, airs from 1 to 5 a.m. in my time zone. Itâs syndicated on over 600 stations and boasts Ânearly three million listeners each week. Most of the time, the talk of space aliens and ghosts lulls me to sleep, but not when my favorite guest, David Paulides, is at the mic.

Paulides, an ex-cop from San Jose, California, is the founder of the . His obsession shifted from Sasquatch to missing persons when, he says, he was visited at his motel near an unnamed national park by two out-of-Âuniform rangers who claimed that something strange was going on with the number of people missing in Americaâs national parks. (He wouldnât tell me the place or even the year, âfor fear the Park Service will try to put the pieces together and ID them.â) So in 2011, Paulides launched the , which catalogs cases of people who disappearâor are foundâon wildlands across North America under what he calls mysterious circumstances. He has self-published six volumes in his popular , most recently Missing 411 Hunters: Unexplained Disappearances. Paulides expects , a Âdocumentary codirected by his son, Ben, and featuring Survivorman Les Stroud, to be released this year.

Last May, I met him at a pizza joint in downtown ÂGolden. The gym-fit Paulides, who moved from California to Colorado in part for the skiing, is right out of central casting for a detective film.

âI donât put any theories in the booksâI just connect facts,â he told me. Under âunique factors of disappearances,â he lists such Ârecurring characteristics as dogs unable to track scents, the time (late afternoon is a popular window to vanish), and that many victims are found with clothing and footwear removed. Bodies are also discovered in previously searched areas with odd freÂquency, Âsometimes right along the trail. Childrenâand remainsâare occasionally found improbable Âdistances from the point last seen, in improbable Âterrain.

Itâs tempting to dismiss Paulides as a crypto-kookâand some search and rescue professionals doâbut his books are extensively researched. On a large map of North America on his office wall,

Paulides has identified 59 clusters of people missing on federal wildlands in the U.S. and southern Canada. To qualify as a cluster, there must be at least four cases; according to his pins, you want to watch your step in Yosemite, Crater Lake, Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and Rocky Mountain National Parks. But then, it would seem you want to watch your step everywhere in the wild. The map resembles a game of pin the tail on the donkey at an amphetamine-fueled birthday party.

Paulides has spent hundreds of hours writing letters and Freedom of Information Act requests in an attempt to break through National Park Service red tape. He believes the Park Service in particular for fear that the sheer numbersâand the ways in which people went missingâwould shock the public so badly that visitor numbers would go down.

Paulides brought along a missing-persons activist named Heidi Streetman, an affiliate faculty member at Denverâs Regis University who teaches research methods. After reading the Missing 411 series, she became frustrated that there was no searchable Âdatabase for families of the disappeared. In 2014, she floated a petition titled It now has over 7,000 signers, with a goal of 10,000.

Streetman, a spirited 56-year-old who spent her childhood camping all over Colorado, is beset with the case of Dale ÂStehling, a 51-year-old Texan who vanished on on a 100-Âdegree Sunday afternoon in June 2013. The trail is rated moderate, but it was hot and Stehling didnât have water. At the petroglyphs, where he was last seen, there is an intersection with an old access trail, where his wife, Denean, believes he may have left the main trail. âIf there was a way to get lost, Dale would find it,â she says.

But even if Stehling had taken the wrong, overgrown path, he surely would have realized his mistake and backtracked. Maybe he collapsed in the heat. But rangers searched that area extensively on foot, with dogs, and in helicopters with firefighting crews. They sent climbers rappelling down cliffy areas and collected a whole trunkâs worth of knapsacks, cameras, purses, wallets, Âwater bottles, and binocularsânone of them Stehlingâs. The park superintendent, , a 32-year Park Service veteran, still holds search and rescue training exercises in the area, just in case they come across a clue. âThe thing that gets me,â he told me, âis in all my years with the Park Service, I donât recall five cases like this.â

It’s hard to put your hunches and suspicions to rest. We’ll never know for certain what happened to Joe Keller.

Itâs not likely that legislation would help the Stehling family, but an amendment to an existing law recently made it easier for volunteer search and rescue outfits to access federal wildlands with less red tape. The issue of permit approval is largely one of liability insurance, but the expedited access for qualified volunteers to Ânational parks and forests, and now they can search within 48 hours of filing the paperwork. More such laws would make things easier for experts like , 63, a retired Michigan State Police detective who now specializes in backcountry search and recovery. Neiger lauds Streetmanâs database and wants to take it further. Heâd like to see a searchable resource that gives volunteers like himself the same information that government officials haveâincluding case profiles, topo maps, dog tracks, and weather.

On February 4, 2016, Keller went to Denver to attend a ceremony for the inaugural . With families of the missing gathered around them, legislators passed resolutions creating the annual event. Keller stood in the capitol, listening as his sonâs name was read aloud. It was one of 300.

In late May 2016, I visited Conejos ÂCounty. A month earlier, two Antonito men had been reported overdue from a camping trip to Duck Lake, less than three miles southwest of the Rainbow Trout Ranch, during a spring storm that dumped two feet of wet snow. Teams were called in from MinÂeral and Archuleta Counties, along with the ski patrol, based 100 miles west on Highway 17. One of the men managed to struggle back to Horca; the ski patrol eventually found the frozen remains of the other.

The search had also resumed for Joe. Earlier in May, more than 30 volunteers, including Keller, Collin, and 11 dogs from the nonprofit , had spent about a week crisscrossing Conejos Canyon. The mission was to either find a needle in a haystack or to significantly reduce the probability that the youth was in a 2.9-mile ÂraÂdius of the point last seen.

The search was organized by the , a Minnesota nonprofit that, since 2007, has helped more than 40 families with loved ones missing on public land. It was created by David Francis, a retired Naval Reserve captain, after his 24-year-old son, Jon, disappeared in Idahoâs Custer County in 2006. in a deep ravine the next year by paid members of the Sawtooth Mountain Guides. âCuster County is the size of Connecticut,â Francis says. âThe search and rescue budget was $5,000. If you go missing in a poor county, youâre gonna get a short, somewhat sloppy search. In my mind, thatâs the national disgrace. Everybody knows someone with cancer. But itâs a minority who know someone gone missing.â

The May search for Joe turned up no sign. But bushwacking off the Duck Lake Trail, about three and a half miles southwest of the ranch, Keller and Gwaltney came upon a sleeping bag, a cook pot, a tarp, and some bug sprayâthe gear of the lost campers.

One sunny afternoon, I went looking for Sheriff Galvez and found him outside the Conejos County Jail, on the north side of Antonito, directing inmates in orange jumpsuits as they planted flowers. He wore jeans and a gray canvas shirt, with a pistol on his belt and reading glasses propped on thick salt-and-pepper hair. It was clear that heâd rather orchestrate landscaping details than talk with the press, but who can blame him? The department has taken a beating on Facebook, Websleuths.com, Dateline, and the . It would be one of our only conversationsâas this article went to press, Galvez didnât return repeated calls and e-mails from șÚÁÏłÔčÏÍű.

âItâs been a rough year and a half,â he told me. After the Keller search and the hunt for the Duck Lake campers, he said, âI donât agree that I should be in charge of search and rescue on federal lands. Iâm thinking of going to the state senators and saying Iâd like to be backed out of that, because I donât have a $90 million budget.â The starting salary for his five deputies is $27,000. âItâd be more Âeffective, I think,â he said. âWeâre a small department, a small community. I hear stuff like, âI canât go, my equipment broke down.â â

Frustration between Galvez and Keller had continued to roil. âWe had dogs, hikers, aircraft,â the sheriff said. âHorseback, drones, scent dogs, Âcadaver dogs. We had so many resources, it was unÂreal. When searchers took a break, he criticized all the resources. Cut everybody down.â

âThis is an ongoing investigation for a missing person,â he continued. âWe have no evidenceâheâs just missing. It looks more like that than anything else. Over 18, you can run away all you want. If Joe was to call us, show me some proof heâs OK, Iâd close it up.â

Before I left Conejos County, I took a run up Forest Road 250. I parked at a turnout in front of a massive ponderosa pine with Joeâs missing-person poster stapled to it, then jogged down to the point last seen and tried to retrace his run. Based on the varying sniffer-dog evidence, some figure that he ran up the road a ways, rounded the first or second bend, then got into trouble. I Âslowly shuffled upriver. A truck or SUV passed every three minutes or so. Locals told me that in July, the traffic on Forest Road 250 is even heavier. Wouldnât someone have recalled seeing Joe if heâd stayed on the road? After my run, I rinsed my face in Spectacle Lake; according to Duffy, R.C. could tell him Iâd been here.

On Wednesday, July 6, John Rienstra, 54, a search and rescue hobbyist and endurance runnerâand a former offensive lineman for the Pittsburgh Steelersâ in a boulder field below the cliff band.

âI heard there had been a lot of searching for two and a half miles,â Rienstra said. âI started looking for rapids, cavesâcliffs, of courseâand right at two and half miles, there is a place to pull off the road, and there were cliffs close by. It took me about an hour to get up there to the base of the cliff, and I went left until I ran out of room. Then I turned around and went back toward the ranch on the base of the cliffs and found him.â The area was too rugged for horses or dog teams. When the Colorado Bureau of Investigations came to retrieve the remains, they packed horses in as far as they could, then had to reach Keller on foot.

Joeâs body was 1.7 miles as the crow flies from the ranch. Searchers had been close. In November 2015, Keller and David Van Berkum had come within several hundred yards. âI regret not searching there on the 25th of July,â Keller told me. âThatâs where I wish Iâd started. What part of here would take a life? Itâs not the meadow on top; itâs the cliff.â

âHindsight is always 20/20,â Jane Van Berkum wrote me recently. âBut since there was a blanket of snow, I am not sure they would have found him even if they had chosen to go higher. But it is painful to think that they were that close.â Every day, she said, she and her husband had searched for Joe as part of their ranch activities. âI have sat on the cliffs many times since he went missing and scanned below over and over, and I never saw him,â she said. âThat tortures me.â

The preliminary cause of death, according to David Francis, was âblunt force trauma to the head.â Jane told me he also suffered a broken ankle. It appears that Joe scrambled up and then fellâperhaps the lost-person behavior laid out by Professor Rescue, Robert Koester. Occamâs razor wasnât as dull as it had seemed for most of a year.

Still, Joeâs death remains a mystery to his mother. âThe events do not fit for a one-hour run before dinner,â Zoe says, âafter they had just driven 24 hours straight to get to Rainbow Trout Ranch.â The boys hadnât slept in over a day. Joe had just split wood with his uncle Davidâs 75-year-old father, Doug Van Berkum. She canât see her son running up to the canyon rimâshe insists that he did not like heights and was not a Âclimber. âThere is something we still do not know about what happened, is how I feel about it.â

Itâs hard to put your hunches and suspicions to rest. Weâll never know for certain what happened to Joe Keller. Weâll know even less about what happened to a lot of other people missing in the wild.

One question I had early on was, Are you better or worse off going missing in a national forest than from a Walmart parking lot? I thought I knew the answer. You can see an aerial view of my firewood pile from space on your smartphone. I thought that in the wild, someone would send in the National Guard, the Army Rangers, the A-Team, and that they wouldnât rest until they found you. Now Iâm not so sure.

Correspondent Jon Billman () wrote about mountain-biking legend Ned Overend in March 2016.