Lost in the Valley of Death

Justin Alexander went searching for higher meaning. No one expected the quest to end in a search for his body.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

Two men said goodbye with a godlike river thundering in their ears. Andrey Gapon, a 47-year-old Russian man, had spent three months on a self-made spiritual retreat in the Parvati Valley, deep in the Indian Himalayas. Walking alongside was an American man, 35-year-old Justin Alexander, a seasoned traveler and experienced outdoorsman whoâd impressed Gapon with his wilderness survival skills, having just spent weeks living in a mountain cave. Now Alexander was embarking on a three-day trek to a holy site called Mantalai Lake, where he would camp under the stars with few supplies.

Gapon offered to go with him, but Alexander said it was a journey he wanted to do with a sadhu, a Hindu holy man who renounces possessions in a search for enlightenment. âI didnât want to persuade him not to go,â recalls Gapon, but he was concerned. Just weeks before, Gapon had also trekked to Mantalai, a cluster of pools murky with glacial flour at the source of the Parvati River. The lake lies in a broad basin relentlessly tormented by winds and subfreezing temperatures. At around 13,500 feet, the icy moraine produces no trees for either shelter or firewood. Alexander didnât have a stove or cooking fuel, so Gapon pressed something into his hand, a fitting parting gift to someone who valued both practicality and minimalism: a red windproof butane lighter.

At the trailhead outside Kalga, a village of guesthouses and orchards where the road fades to footpath, Alexander handed Gapon his iPhone and asked him to take his picture to mark the âbeginning of a spiritual journey.â The men hugged, and Alexander walked up the path into the forest. It was August 22, 2016.

Four days earlier, Alexander had blogged about his plan to meditate, practice yoga, and learn from the sadhu during this journey. The final line read, âI should return mid September or so. If Iâm not back by then, donât look for me ;).â

Alexander didnât return. Somewhere in the high reaches of the Parvati Valley, he disappeared.

There is only one road in and out of the Parvati Valley. Itâs a narrow trackâroughly paved in parts, washed-out dirt in othersâalong which rattletrap buses swerve and screech to a crawl with inches to spare as they pass. Mountains rise up one side, and cliffs drop precipitously down the other, often hundreds of feet to the Parvati River below. The milky blue waters, named after a benevolent Hindu goddess of fertility and devotion, seem inviting but can be a powerful, violent force.

The valleyâs hillside hamlets and postcard mountain vistas attract tens of thousands of tourists every year, but those who come here are different from those who speed through the Taj Majal on a or backpack from vibrant temple to sparkling beach as the mainstay of Indiaâs tourism. The travelers who feel drawn to the , more than a full dayâs bus ride north of New Delhi into the Himalayas, quickly settle into a pace of life common in this remote corner of India: a blur of weeks or months spent meditating, practicing yoga, and consuming copious amounts of hash grown in clandestine plantations or from plants that sprout wild along river and road.

Many see the Parvati Valley as a stage or even the culmination of their quest for enlightenment.

The valley, where gods are said to have meditated for 3,000 years, is particularly alluring to the spiritually curious. Every summer, the valley hosts a , a counterculture congregation that promotes anti-consumerism and utopianism. Many visitors come to venerate Shiva, husband of Parvati and one of the most exalted and popular gods in the Hindu pantheon. Among Shivaâs most resolute followers are the sadhus who dress and live in emulation of the gods, but many Westerners are also lured by his familiar symbolism as the dreadlocked master of meditation and yoga and the supreme renouncer of possessions, and follow suit. Those who follow this path view the Parvati Valley as a penultimate stage or even the culmination of their quest for enlightenment. It is a place where wandering ascetics, New Age neophytes, and determined religious tourists flock, believing that the bumpy road to nowhere instead leads to long-sought answers or higher understanding. While Parvati is purifying water, Shiva is transforming fire.

The valley may appear idyllic, but it holds a dark past. Over the past 25 years, according to both official and unofficial reports, at least two dozen foreign tourists have in and around the Parvati Valley. Among the vanished are people from Canada, Israel, Japan, Italy, Czech Republic, Russia, Netherlands, Switzerland, and Australia. Distraught loved ones post stories of the missing on social media, online message boards, and travel forums with scattered details and few clues.

Many cases reek of foul play. In 1996, Ian Mogford of the UK in the Parvati Valley after reportedly telling his father over the phone that he had befriended a sadhu. âIt is not beyond the realms of possibility that… for some reason my son got attacked and is lying on the bottom of a gorge,â Mogfordâs father told the Telegraph. Others might have been targeted after being caught up in the lucrative drug trade, buying hash at the source and selling it to tourists. After Bruno Muschalik, a backpacker from Poland, in the summer of 2015, his father maintained that local drug mafias were to blame. Some of the missing are ; in 2000, a British man, his fiancĂ©e, and her teenage son were brutally attacked while camping above the Parvati Valley. Only the man survived. Most simply vanished without a trace in this one sliver of the subcontinent.

When a body does turn up, it is often pulled from the torrential churn of the Parvati River, which during the monsoon summer is capable of carrying a person downstream or consuming one in its undertow in a blink. But it is the dearth of bodies that turns the Parvati Valley into Indiaâs backpacker Bermuda Triangle.

In the rest of the country, hotel and guesthouse owners are required by law to log their patrons into an online database, but in the Parvati, the vast majority travel in and out without record. The isolation and lack of regulation only add to the draw. Itâs not difficult or unusual for foreigners to deliberately drop off the radar for the full duration of or even illegally beyond their travel visas. One Israeli man lived in the valley for decades, growing and dealing hash, getting married and having a child, until he was arrested for overstaying his visa.

With conditions ripe for vanishing without trace, a question arises: Did all of these travelers get lost or murdered in the wild, or did some not want to be found?

followed the spiritual crowds to the Parvati Valley, but he never walked the typical path. He was born in Sarasota, Florida, as Justin Alexander Shetler, but later in life began using his middle name as his surname, and moved around the West after his parents divorced. He once called himself reserved and a self-proclaimed loner who found solace in nature, but others knew him as someone who thrived on human connection.

When he was 16, his mother, Suzie Reeb, withdrew Alexander from high school and enrolled him in the Wilderness Awareness School. The nature-based educational program near Seattle, Washington, was co-founded by Jon Young, a protĂ©gĂ© of Tom Brown Jr. who established the internationally acclaimed New Jerseyâbased Tracker School. When Young brought Alexander, a promising survivalist, to the New Jersey school, the teenager arrived with starry-eyed idealism and befriended 22-year-old instructor Tom McElroy. Alexander instantly impressed McElroy with his deep knowledge and dedication, and the pair would head out on expeditions tracking wolf packs on foot. He went on to teach at a childrenâs camp associated with the school.

It is the dearth of bodies that turns the Parvati Valley into Indiaâs backpacker Bermuda Triangle.

Alexander established a reputation for being fearless. When he heard from someone at the Tracker School how to fall safely from a tree, he climbed 50 feet up and let go. The technique is to grab and release branches to gradually slow your fall, but Alexander missed some, rag-dolled the last 20 feet, and slammed into the ground, narrowly avoiding cracking his skull on nearby rocks. âWhen my greater fear told me no, Justin would just go for something,â McElroy says. But Alexander was also adept in the more contemplative forms of awareness, including Brownâs practice of returning to a single square foot in the wild, a âsit spot,â to listen and notice slight changes in the environment. Tracy Frey, who ran the childrenâs camp where Alexander taught and who remained friends with him afterward, saw many teenagers arrive with not only a desire to learn survival skills but also a yearning to tap into a deeper spirituality in nature. Alexander epitomized this. âHis life was about looking for something bigger,â Frey says.

Alexander got his GED and then held jobs as a wilderness EMT and a massage therapist. He also worked at an alternative school in Palo Alto, California, while fronting a Bay Areaâbased band called , which toured as far as Japan. In 2009, he joined a friend in Miami to work for a tech startup focused on luxury goods, which allowed him to travel, eat at Michelin-starred restaurants, and stay in fancy hotels. âHe put aside the nature man and began traveling the world in high style,â Reeb says. But the glitz of the job didnât impress Alexander for long.

In December 2013, at age 32, Alexander announced his retirement. Disenchanted and restless, he sold the majority of his belongings, packed a backpack, and took off. In the first post on his travel blog, , he wrote: âI am running from a life that isnât authenticâŠIâm running away from monotony and towards novelty; towards wonder, awe, and the things that make me feel vibrantly alive.â He spent the next two-and-a half years on the road, backpacking through South America and Asia, and driving his motorcycle around the United States.

On the surface, Alexander embodied the âI quit my job to travelâ trope, and he amassed a horde of followersâmore than 11,000 on his Instagram account alone. Many gravitated to his stories of climbing the Brooklyn Bridge at night, partaking in a shamanistic ritual in Brazil, undertaking a monkâs initiation ceremony in Thailand, and helping build a school in earthquake-wracked Nepal in the spring of 2016. Others were drawn to what his adventures represented: Alexander was minimalist but not rejectionist. His smartphone didnât disgust him; it enabled him to tell his story. And his path appeared to be one not of disassociation but of action, as if he were the protagonist in his own epic novel. But beneath Alexanderâs glamorous tales was a person searching for higher meaning, sometimes at the expense of sensibility. He once said that his life was about âwalking that razorâs edgeâ between living in modern society and a free existence.

âI think he wanted to push himself even beyond his own norm, and it probably snowballed into doing things that were more and more risky,â McElroy says. âEventually he pushed the limits a little too far.â

In mid-June 2016, with thunderclouds disgorging monsoon rain on the subcontinent, Alexander crossed the border from Nepal into India. He arrived in the city of Varanasi, one of the countryâs strongest spiritual magnets, where Hindu pilgrims bathe in the holy Ganges River to have their sins washed away. Alongside, bodies are burned at designated ghats, concrete steps that fringe the river, where fires consume flesh in round-the-clock cremations. To have your remains carried downstream by the holy waters is a blessing that frees your soul from the endless and torturous cycle of reincarnation.

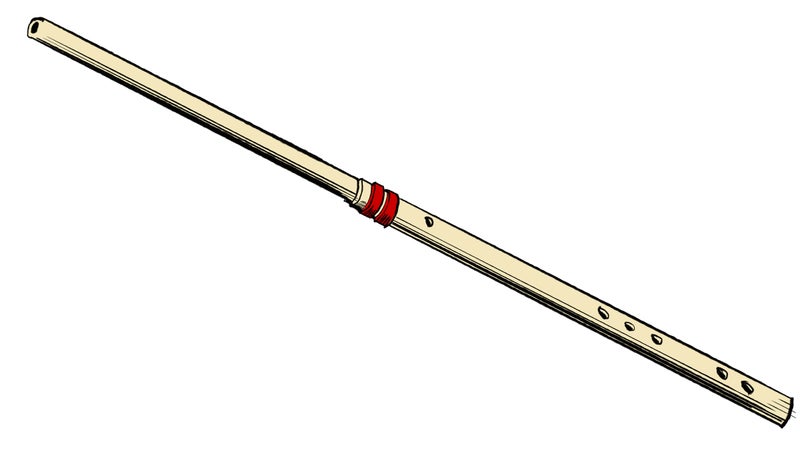

There, Alexander met a dreadlocked foreigner who played a bamboo flute and said, in a thick German accent, that he had been living in India for the past 20 yearsââa simple life, with few possessions,â Alexander wrote online in admiration. It was likely the first foreigner heâd met who had been living in the country long-term.

Beneath Alexanderâs glamorous tales was a person searching for higher meaning, sometimes at the expense of sensibility.

Carrying a flute that he had turned into a walking staff, Alexander headed northwest to the capital of New Delhi, where he bought a used black Royal Enfield Bullet 500 motorcycle and named it Shadow. For years, he had dreamed of driving over one of the highest motorable mountain passes in the world, the 17,582-foot Tanglang La, and into the remote region of Ladakh, the northernmost tip of India. He rode into the foothills of the Himalayas. Midway through the trip, on July 22, he entered the Parvati Valley.

Alexander arrived determined to head into the mountains, not to smoke away the days in some grubby hostel until his visa ran out. He wrote that he was âfeeling the need for some alone time with mother Himalaya.â When he arrived in the valley, he messaged Christofer Lee, a French traveler Alexander had connected with online a year earlier. Lee had been in the Parvati for three months, and the pair now traveled up the valley to Kalga.

Lee remembers discussions with Alexander about whether he was selling his adventures, posting them online for an audience rather than fully living them. âI think he was at a time in his life when he was asking himself some questions and didnât know what direction he wanted to go,â Lee says. But Alexanderâs next step materialized quickly. The day after he drove into the Parvati Valley, he posted on Facebook his plan to hike into the upper valley and live for weeks in a cave, emulating the lifestyle of the sadhus. âItâs something Iâve been called to do for years now. Not to renounce the world or become enlightened but to wander alone in these majestic Himalaya,â he wrote. âP.s. If I get into trouble or begin to starve, I can hike down to a village and get help or eat. I wonât die.â Alexander wasnât after complete solitude, but he wanted the space to quietly meditate and actively test his mettle while living in a cave with few supplies.

On July 28, Andrey Gapon met Alexander in Khir Ganga, a ramshackle camp of wooden pole, tarpaulin, and corrugated aluminum structures that many Parvati Valley visitors see as the end point of their informal pilgrimage. The Russian was instantly drawn to the tall, broad-shouldered American man with an eagle tattoo across his chest who said he was living in the mountains. Alexander led Gapon to his cave, a four-foot-tall hollow hidden above the camp on a forested hillside. The space was cramped, but Gapon remembers Alexander was keeping it âforest clean.â He had collected wood to keep his pit fire rolling each night and had candles to read by in the evenings. Gapon was impressed. Here was a man who wasnât just surviving in a cave but seemingly thriving. âIâve been living in some caves in the Indian Himalayas for the last couple weeks,â Alexander posted online on August 13. âIt was smaller and leaker [sic] than I hoped, so most mornings I hiked an hour down the mountain to sit in the sacred hot springs of Khir Ganga to warm up.â

On one occasion, Alexander told his followers online, shortly after he arrived in Khir Ganga, a sadhu named Sat Narayan Rawat beckoned him into a smoky, stone-walled hut just below the hot springs. The sadhu was short and slim, wore a saffron dhoti (a wrap around his waist), and had long, matted dreadlocks characteristic of Hindu ascetics. Many sadhus live in the valley or accompany travelers there in warmer months, but Rawat stood out because of the large growths on his knees, wrists, and elbows, some as large as a lemon.

To many who lived in the area, Rawat was not an authentic sadhu. Instead, many referred to him as a âbusiness baba.â (Baba is often a colloquial word for sadhu.) These false holy men look and dress the part but wander the country searching not for spiritual enrichment but for cash, drawn from those who are curious enough to pay to be in their presence. Rawat had a reputation in Khir Ganga for petty theft from negligent tourists, and Lee never had a good feeling about the sadhu. âSome babas are very charming and outgoing, but this baba was rough and crude,â he says. âMaybe he was a great person, but there was something that was very hard and very aggressive with this spirit.â He warned Alexander to be careful.

Still, the American man visited Rawatâs hut often. He would sit on mats around the sadhuâs fire pit smoking chillum, watching him perform complicated yoga asanas, and, when a Hindi speaker was present to translate, learning from him. Rawat told Alexander he had cut off his penis in an extreme repudiation of lust. âOver the next two weeks we became friends,â Alexander wrote on his blog. âI think.â

Over his stay in the valley cave, Alexanderâs curiosity in the sadhu way of life turned deeper. âIâve heard stories about the magical powers of these Babas,â he wrote on Instagram on August 15. âThey can see into your soul and know your past and future. They can bless or curse. They are holy men but wild, and are even above the law in India. Police wonât arrest them; even for murder, which happens Iâm told.â Alexander felt a growing fascination with what sadhus represented and how they lived their livesâsolitary and untetheredâand he had come to trust Rawat. âHe says most babas are fake, that they enjoy money, women, and posing for tourist photos for cash; basically fake-holy-man bums. But he assures me that he is the real thing.â

Few countries on earth draw spiritual tourists in such zealous droves as India. They come to sit where the Buddha achieved enlightenment under a bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya; they come to wander Rishikesh, where the Beatles spent weeks in an ashram in 1968 penning songs; and they come for the , believed to be the largest religious gathering on the planet, where in 2013 an estimated 30 million people congregated in a single day. But the country has a way of taking hold of the spiritually curious and turning innocent idealism into devoted fervor. It is a phenomenon known as , not a clinical diagnosis but a spectrum of behavioral changes that range from the benign (disorientation and anxiety) to the extreme (a total detachment from reality).

âIndia inspires in Westerners such intense emotion that it sometimes causes in travelers a kind of delirium, a madness that vanishes spontaneously when they return to their home country,â writes RĂ©gis Airault, a psychiatrist who worked for the French consulate in Bombay and published a book in 2000 called Fous de lâIndeâo°ù Crazy in India. âFor India speaks to the unconscious: it provokes it, makes it boil and sometimes overflow. It brings forth the buried, from the deep layers of our psyche.â

At his center in New Delhi, Sunil Mittal, a consultant psychiatrist and director of the Cosmos Institute of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, sees about one foreign tourist per week that he would describe as having India syndrome. Some arrive with an emotional or psychological issue in their life and succumb to a heady mix of culture shock, overwhelming unfamiliarity, alluring exoticism, and, in most cases, drugs. âItâs like a bomb,â Mittal says. One foreign traveler Mittal treated had been found wandering near the Taj Majal, disoriented and confused. âHe left his backpack, passport, everythingâand just ran away.â Some become so infatuated with India that they find a quiet niche or anonymity among the throng and never return home.

Others deliberately flock to holy centers in India to study meditation, yoga, and spirituality and become enamored of yogis or gurus, often dressing up as a priest or sadhu themselves. âOn the path of a spiritual quest, a person questions all of their ingrained values,â Mittal says. âThis can lead to a state of emptiness, loss of direction, or a sudden feeling of exaltationâand then not knowing how to handle it.â One of the more severe cases he has seen involved a young American woman who had been in India for four months and was found living in an ashram dancing half-naked each night for the attendees. When confronted by Mittalâs team, she was adamant that she was an apsara, a female mythological spirit who tempts yogis and priests to test their resolve.

The majority of cases Mittal sees are the result of foreigners pushing themselves into increasingly dangerous situations, emotionally and physically, on some form of a spiritual quest. For some, enlightenment lies at the end of a hash-packed chillum; for others, at the top of a snowcapped mountain; and for others still, in the quiet company of a holy man who promises wisdom.

After three weeks around Khir Ganga, Alexander emerged from his cave and descended along the forest trail to Kalga, the Parvati River swollen with summer rain below him, determined to take a greater step: higher, in both elevation and hopeful revelation. Rawat had invited him on a âspiritual trekâ toward the riverâs source at Mantalai Lake. âHe wants to mentor me in the ways of the Sadhu; of ShivaâThe First Yogi,â Alexander wrote in his final blog post. âHe follows a strict spiritual routine that I know nothing about, and I am intensely curious… I want to see the world through his eyes, which are essentially 5,000 years old, an ancient spiritual path. Iâm going to put my heart into it and see what happens…Â Maybe Baba Life will be good for me.â In his gray daypack, Alexander packed a kilogram of rice, some oats, nuts, raisins, tea, sugar, and flour. He carried the clothes on his back, a sleeping bag, a machete, and a few other essentials, but no tent or stove. In his hand he clutched his flute-staff.

Wherever her son traveled, Suzie Reeb rarely felt nervous. But this time was different. âThe only time Iâve been freaked out and anxious was when he was in India,â she remembers. They had emailed and messaged frequently while Alexander was traveling, but she had a âforebodingâ feeling about the sadhu. She told her son that she was worried about his plan but didnât try to convince him not to go. âI never wanted to be the kind of mother who projected fear and anxiety onto my child,â she says.

Following her friend online, Tracy Frey had noticed a shift in the tone of Alexanderâs photos and writing. She found his final post âdistressingâ and worried that he was pushing himself too far. âMy worry was that he needed to keep doing more and more, and at some point, thatâs going to catch up to you,â she says. âI was worried because even though Justin has always been a trusting person, heâs also an incredibly good judge of character.â But when Frey read what Alexander wrote about the sadhu before he departed for Mantalai Lake, something was unsettling. âIt didnât feel like he was accurately judging this man.â

Alexander was confident about his journey, but something was weighing on him as well. Before leaving for Mantalai Lake with Rawat, he joked to Gapon, âIf I die, write something nice about me on Facebook.â Alexander mentioned that one day it would be nice if there was a website where peoples' digital trails could serve as a eulogy to their lives. Still, desire for a life-changing experience overwhelmed fear. âI think he came to a point where he realized that just being able to survive in tough conditions is not enough to really be free,â Gapon says. On August 22, the Russian man walked his new friend through the orchards in Kalga to the trailhead above the river, gave him a red butane lighter, and said goodbye.

Above his final blog post, Alexander had attached a video. The eerie series of clips opens with him sitting on a rock, draped in a gray shawl like a monk, surrounded by silhouettes of pine trees fading into the fog. He then walks barefoot through a meadow, drinks from a mountain stream, and lights a fire in his cave before lying down. The next shot is of the Parvati River, thrashing and foaming and spewing mist. The mist fades, and Rawat appears through a cloud of smoke, in his hut, smoking a chillum. The video fades to black.

By the end of September, Alexander hadnât returned from the mountains. His mother, on the other side of the world in Portland, Oregon, started to become concerned. She knew he wouldâve called at the soonest opportunity. Those heâd met in the Parvati Valley were also growing worried. After receiving a message from a concerned mutual friend, Gapon, who had returned to Russia earlier in the month, messaged Lee, who was still in Kalga. The Frenchman hiked three hours to Khir Ganga to find the one person he knew was with Alexander last. He was surprised to find Rawat sitting in his hut.

When Lee and several other friends confronted him, the sadhu became angry, saying, âJustin is crazy.â Rawat claimed the American had left him after they met some trekkers near Mantalai Lake and that Alexander headed higher up the valley with them. Lee didnât believe it, so he immediately filed a police report at the small station nearby.

Reeb didnât believe the story either. She boarded a plane to New Delhi on October 9, connecting with a friend of Alexanderâs, Jonathan Skeels, en route in London. Skeels had briefly crossed paths with Alexander over the July 4, 2015, weekend in Big Sur, California, and had remained in touch with him. Skeels was struck with the manâs gentle character, his compassion, and his adventurous spirit. âJustin led a life that many people wanted to lead,â Skeels remembers. He felt compelled to help search. In India, he and Reeb met with U.S. embassy officials in the capital before traveling north into the mountains. Meanwhile, Lee and a group of Indian trekking guides familiar with the area searched around Khir Ganga on foot.

On October 15, two days after Reeb had filed an official missing personâs report at the district police office in the city of Kullu, near the mouth of the Parvati Vally, Rawat was apprehended and brought before her and Skeels. The sadhu gave a different version of what happened at Mantalai Lake than what he had told Lee in Khir Ganga. Rawat divulged that a third person, a porter heâd hired, had accompanied them to Mantalai. The sadhu now claimed that the last time he saw Alexander was after the trio had stopped for tea on their way down from the holy lake. Rawat sent the porter ahead to begin preparing food, Alexander followed, and Rawat held back because his knees were hurting. When Rawat joined the porter at an old forest service hut, Alexander hadnât arrived. Rather than reporting the American missing to the police, the porter and the sadhu descended to Khir Ganga and said nothing.

Sitting six feet from one of the last people to see Alexander alive, Reeb struggled to keep her composure. In her eyes, Rawat at best knew more than he was saying and at worst might have taken her sonâs life. It had been a month since he was supposed to have returned.

As news spread in the valley of the missing American, three Indian hikers came forward with a lead. On September 3, they said, they had encountered Alexander, the sadhu, and the porter near the murky pools at Mantalai and had taken a picture with the American. They said the sadhu was arguing with Alexander when they first approached, and Alexander told them that he was hungry and tired and wanted to descend. The story contradicted both of Rawatâs accounts.

Three days after Skeels and Reeb filed the report, police and a small search team that included Skeels landed by helicopter along the trail below Mantalai Lake. After two hours, the police flew back to Kullu, leaving Skeels to continue on foot downstream to Khir Ganga. With him was Brijeshwar Kunwar, an engineer from Bangalore who was on holiday climbing a nearby mountain and had offered his skills to help. Most of the trail from the lake is a gradual traverse across moraine and alpine meadow, but there is one section, as the trail approaches the tree line, where it fringes a cliff edge above the river. The Parvati runs fast near its source, especially here, where the valley forces it together into a narrow pinch, and especially in summer. The waters that course from source to valley mouth are perpetually vicious, but when fed by monsoon rains and melting snow, the river morphs into a torrential beast. âItâs like Death Valley,â Kunwar says. âItâs very easy to have accidents in that area, no matter how conscious you are.â

Reeb struggled to keep her composure. In her eyes, Rawat at best knew more than he was saying and at worst might have taken her sonâs life.

The pair leapfrogged along the left riverbank, scanning the boulder-strewn turns and grassy slopes for anything out of the ordinary. At around 4 p.m., Kunwar reached the cliff-edge section of trail above a 100-plus-foot, near-vertical rock slide down to boulders and churning waters. Over the roar of the river, he cried out, âI see the flute!â

Skeels and Kunwar scrambled down the scree and slippery rock to the riverbank. A bamboo flute-staff was stuck upright in the ground just up from the milky waters. Nearby, they also found a black waterproof backpack cover, a gray scarf, and a red butane lighter.

As Skeels searched the valley by helicopter and foot, he couldnât help but imagine his friend calmly stepping out of the mountains, safe and just a little late. Now he knew that might never happen. Staring down at some of Alexanderâs unmistakable belongingsâjust 11 miles from where hundreds of backpackers gathered and reveled in tents at Khir Gangaâwas a crushing moment.

Through their investigation, the police who oversee the Parvati Valley favored explanations that didnât point to another murder of a foreigner in their district. âInitially, my notion was that he had taken some drugs and gotten lost,â says additional superintendent Nishchint Singh Negi, who has dealt with many of the cases in his green-walled office in Kullu. âWe have so many instances of that, people falling in the river.â But after finding out that Alexander had spent so much time with a sadhu, had lived in a cave, and carried a flute-staff, the police included his âdonât look for meâ post in their official report as important context for his disappearanceâthat he could have been yet another foreign backpacker with a case of India syndrome who had dropped off the grid on purpose.

âWhen Justin got lost, there was so much effort to find him,â says Negi, adding that the police had never before used a helicopter to search for a missing foreigner. But according to one person close to the search, the district police were âunequipped and unmotivatedâ to fully investigate and only made an effort to appease the family and the U.S. embassy. âI was fighting for my sonâs life,â Reeb says. âI was fighting for them to consider that he was really missing.â

As the first week of the search continued, the best hope for information remained with the sadhu, who was being held in remand in a cell in the valleyâs small station. Just after 7 p.m. on October 21, the police officer in charge of Rawatâs post stepped outside to relieve himself. According to the official report, when the officer returned, he found that the sadhu had with his dhoti.

Skeels and McElroy thought it was a strange coincidence the sadhu had supposedly killed himself days before his remand was set to expire, in a valley where the police make an effort to avoid drawing attention to the mysterious disappearances of tourists in their jurisdiction. Reeb was devastated. âI felt we lost the last thread of hope of finding Justin and finding out what truly happened.â

After a frantic two weeks of searching, few leads remained. Alexanderâs iPhone, which he used to post on Instagram and Facebook, has never been recovered. Police apprehended and interrogated the porter but released him, his story aligning with Rawatâs revised version of events.

The police effectively closed the case of Justin Alexanderâjust one more disappearance in the Parvati Valley. âWe cannot conclude the possible reason of death,â the final report read, âbut we presume that he might have been abducted by someone with the intention to kill him.â In the district post in Kullu, his name was added to the list of vanished foreigners, status âuntraced.â

After the flute was found, Tom McElroy flew to India to see if his experience in tracking could uncover clues. Looking down the rock slope, he noticed what might have been an impact site near the riverbank, suggesting a fall. Did Alexander slip and tumble into the river? Was he pushed? Or had he simply discarded his flute and butane lighter near the churning waters? McElroy thought of his friendâs legendary survival skills. âYou couldnât help but think that he was going to wander around the corner, all skinny and emaciated, and say, âTom! What are you doing here?ââ Even long after Alexander disappeared, Lee still saw a window of possibility that the American still might reappear. âIf thereâs one guy who could jump through that window, it would be him,â he says.

For some who met Alexander in the Parvati Valley, while it seemed unlikely, it also didnât seem far-fetched that he might have voluntarily disappeared. âThere was a smile,â says Gapon, referring to the winking emoji Alexander used as punctuation at the end of his final blog post. âBut he partly meant it. He was looking for liberation. He was ready to play big, and when you play big, itâs all or nothing.â Skeels, however, thinks that sleeping in a cave in the Himalayas was simply Alexander pushing himself physically, and that the âdonât look for meâ line was written to attract followers.

As a teenager, McElroy remembers, Alexander wanted to live a near-mythological saga. One of his favorite books growing up was Joseph Campbellâs 1949 classic, , in which the author presents an archetypal âheroâs journey.â The first step is a feeling or call to adventure, Campbell writes. When a quest has been chosen, a teacher leads the hero-to-be through a series of tests to a stage of metamorphosis, and then to the apotheosis of the journey: a great realization. Later, the hero returns as a newly made âmaster of two worlds,â spiritual and material.

In the Parvati Valley, this desire compelled Alexander higher. He replaced any form of hesitation with undaunted openness, he papered over any sense of skepticism with blind trust, and he quickly matured any honest curiosity into determined action.

Reeb stops short of revealing some of the things âthat were on his mind and heartâ but says her son was searching for a deeper meaning behind all his years on the road, and what lay ahead. âI think he was on a spiritual quest,â she says. âI mean, he ended up in a cave in India.â

However Alexanderâs journey ended, something happened at Mantalai Lake. In the September 3 photograph taken by the hikers, Alexander is wrapped in his gray shawl. He appears calm and stoic. Maybe Alexanderâs realization wasnât about himself but about the man he trusted to guide himâthat he came to see the holy man as a fraud, unable to offer what he sought. Itâs possible Alexander found what he was looking for: a dreamlike revelation while sitting near the source of a holy river, listening to the minute motions of nature, that showed him the way forward. Or maybe at the end of the trail, he found nothing; that the harder he tried, the more it felt like he was grasping at mistâchasing tendrils higher and higher into the mountains.

Each summer, monsoon rains return to the Parvati Valley, turning the hills lush and the river turbulent. Tourists return as well, despite the valleyâs dark history. The lure of high mountains and high meaning is too strong.

During the frantic October search, Alexanderâs other belongings were found scattered around the Parvati Valley. His large green backpack, containing most of his belongings, was collected at Om Shanti Guest House in Kalga, where heâd stored it before his trip with the sadhu. Heâd packed the bag neatly with some souvenirs, his motorcycle insurance, and his passport. There was a first-aid kit and an extensive array of survival items. Tucked inside was a piece of lined paper on which Alexander had drawn a nag chhatri, a rare trillium flower found at high elevations in the Himalayas that is sought out for its healing properties, a natural panacea. Above the drawing, scribbled in black pen, Alexander had written, âHappiness comes from the freedom and capability to dream a life into reality.â

Shadow, his black Royal Enfield, was found parked just below Kalga. In early November, as the official investigation waned, Skeels drove the motorcycle, with Lee and McElroy following in a support vehicle, along the cliff-cut roads heading out of the Parvati Valley towards the 17,582-foot Tanglang La, the pass into Ladakh, to continue their friendâs journey. Strapped to the back of the motorcycle, with a white star painted over each ear, was Alexanderâs helmet. The Parvati River thundered below.