A lot of what you need to know about the hunt for Forrest Fenn’s treasure is in the numbers, but the numbers are pretty fuzzy. We know there’s , written by Fenn, containing nine clues that—correctly deciphered—lead to a bronze chest containing gold and jewels worth perhaps two million dollars—but that’s a guess. No one really knows what it’s worth.

Nor do we know how many people have gone out looking for it. Fenn himself is the best source of hunter-numbers, and his figures vary widely: from 65,000 to 100,000 to 250,000. Whatever the real number of seekers, two of them have now died in pursuit and New Mexico Police Chief Pete Kessetas is .Ěý

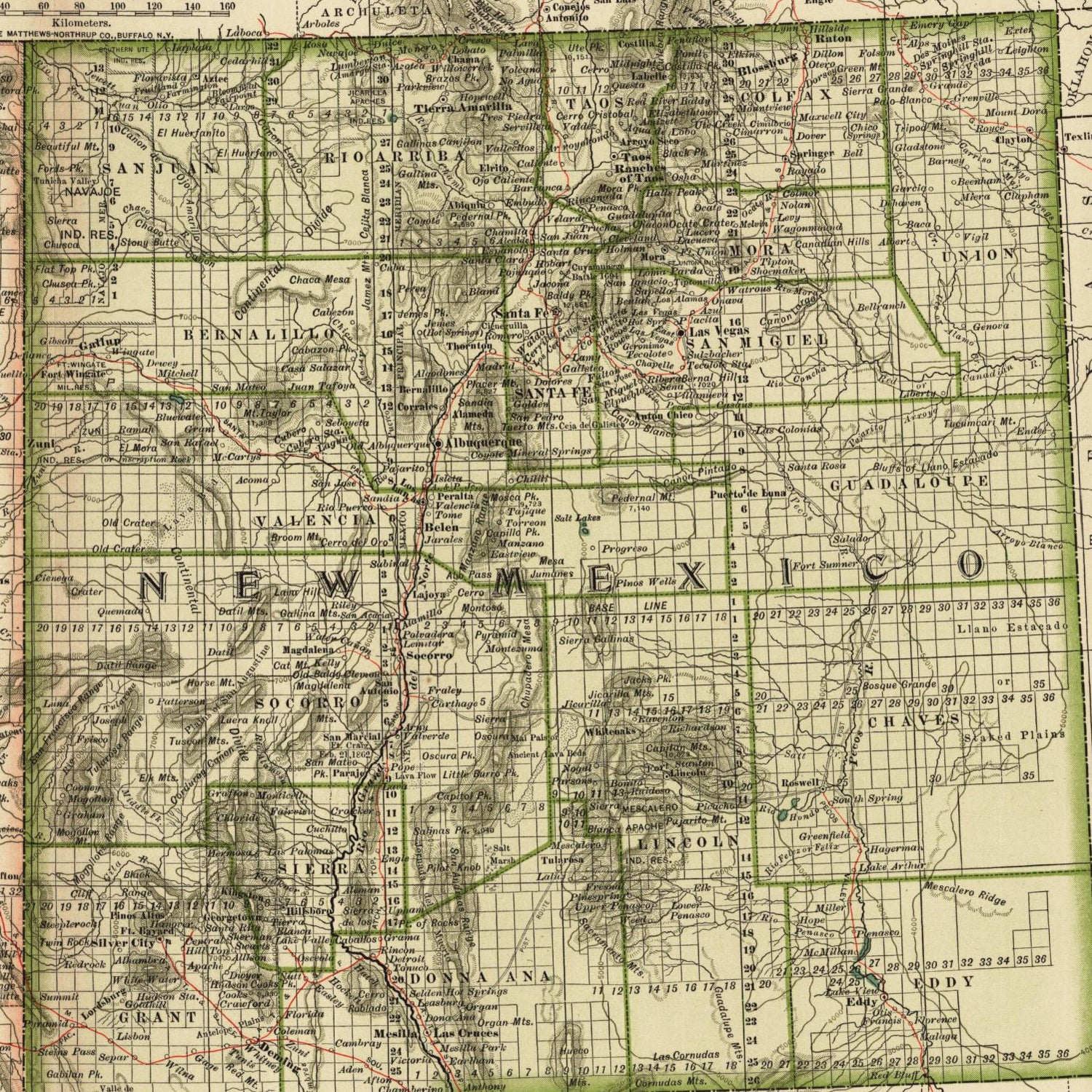

Randy Bilyeu disappeared in January 2016 and his body turned up in July of that year. was found on June 18, just four days after his family reported him missing. Both men were in their 50s, traveling alone near rivers in New Mexico. Wallace’s family called it “God’s plan,” Bilyeu’s ex-wife Linda that “only one man has the power to stop the madness.” Meaning Fenn.

In fact, over the last week, as once-fawning media coverage turned critical of his seven-year-old stunt, Fenn said that he was and was considering calling it off but “had not decided either way.”Â

The two deaths are undeniable tragedies, but calling off the hunt would be a mistake. Whether you’re hunting for treasure or backcountry powder stashes or monster trout on remote streams, there’s some risk anytime you go outside. And assuming the rough accuracy of Fenn’s middle hunter-number, treasure hunting is not much more dangerous than walking down the street in an American city (1.6 deaths per 100,000).

If you compare treasure deaths to outdoor sports, it resembles SCUBA diving (roughly 2 per 70,000) and American football (2 per 100,000). Surfers die at about the same rate, too, but mostly tourists (2.38 per 100,000), not locals (0.28 per 100,000).

The problem with these comparisons, however, is that none factor in the psychology of treasure hunting. The unavoidable rush of thinking you’re on the right track. Gold fever. Police Chief Kassetas said the hunt has “created an environment where people are making poor decisions.”Â

This is true on many fronts. The hunt can be addictive and life consuming. Â It has ruined marriages and emptied retirement accounts. But more than poor decisions, treasure hunting imposes a different logic on the wilderness; it changes priorities. Would you cross that river? No? Would you cross it for a million dollars? I thought so.

That attitude has landed some people in trouble. Fenn treasure hunter Madilina Taylor, of Lynchburg, Virginia, prompted three search and rescue efforts in the same part of Wyoming in a span of four years. The first time she spent four days lost in the woods, the second time she broke her ankle. Still she went back again. After three days, her parked car drew searchers out looking for her.ĚýIn 2015, Seattle treasure hunter Darrell Seyler, who I profiled for şÚÁĎłÔąĎÍř in 2015, was arrested and banned from Yellowstone National Park after search and rescue teams picked him up from the banks of the Lamar River twice in two weeks. Because of the ban, Seyler was actively avoiding park rangers on his second trip, and tried to refuse rescue when they did show up.

The two deaths are undeniable tragedies, but calling off the hunt would be a mistake. Whether you’re hunting for treasure or backcountry powder stashes or monster trout on remote streams, there’s some risk anytime you go outside.

And where a normal hiker would leave word with friends and family—or at least a note on the dashboard—treasure-focused trips are often shrouded in secrecy. With millions up for grabs, some hunters don’t leave good information on where they are going or their planned route for fear of someone poaching their interpretation of the clues.Ěý

Still, if you look at search and rescue numbers—and these stats are even fuzzier—treasure hunters don’t seem to initiate search-and-rescue operations any more frequently than other outdoor sports.ĚýBy way of comparison, from 2005 to 2015 canyoneering in Zion National Park resulted in 221 search and rescue activations—just under two per month. Eleven people died canyoneering in that same time span. Treasure hunting can’t touch that.Ěý

A few days ago Fenn said—to almost no one’s surprise—that he wouldn’t be canceling the hunt. But he may issue some sort of clue or statement to make it safer. This would be in addition to the clues he’s already given and statements he’s already made—“The treasure is not in a dangerous place,” and “Don’t go somewhere an 80-year-old man couldn’t go.”

Fenn has also said previously that he devised the hunt “for every redneck out there with a pickup truck, six kids, just lost his job, his wife, and lacks adventure.” The original idea behind the treasure hunt, he says, was to get people outside, off their screens, into nature.

But send enough people into the woods looking for adventure and some of them are going to perish. The sad message of these two deaths is that Fenn’s scheme seems to be working.