While rowing across the Pacific in 2008, wind pushing him and waves battering him, Italian explorer ��felt an unsettling lack of control.��

Playing in his mind was the story of another Italian explorer, Umberto Nobile, who crashed his zeppelin north of Svalbard after a 1928 polar expedition. Seven men died. The survivors, including Nobile, spent a month wandering the free-floating pack ice, at one point shooting and eating a polar bear, until their rescue. How people react to unpredictable situations fascinates Bellini, a dedicated student of psychology. In the Arctic Ocean, unpredictable situations are a way of life.��

“All adventure is based on hypothesis, which can be very different to reality,” says Bellini. “An adventurer must adapt himself to the environment he faces.”��

����������Ծ�’s newest adventure��highlights and relishes that lack of control. Sometime next winter, he plans to travel to Greenland’s west coast, pick an iceberg, and live on it for a year as it melts out in the Atlantic.��

This is a precarious idea. Bellini will be completely isolated, and his adopted dwelling is liable to roll or fall apart at any moment, thrusting him into the icy sea or crushing him under hundreds of tons of ice.��

His task: experience the uncontrollable nature of an iceberg at sea without getting himself killed. The solution: an indestructible survival capsule built by an aeronautics company that specializes in tsunami-proof escape pods.

“This adventure is about waiting for something to happen,” says Bellini. “But I knew since the beginning I needed to minimize the risk. An iceberg can flip over, and those events can be catastrophic.” Icebergs tend to get top-heavy as they melt from their submerged bottoms, so flips can be immediate and unpredictable. And, of course, so is the weather.

Bellini spent two years searching for the appropriate survival capsule, but most were too heavy to plant on a berg. But then, in October, he contacted aeronautical engineer Julian Sharpe, founder of , a company that makes lightweight, indestructible floating capsules, or “personal safety systems.”��

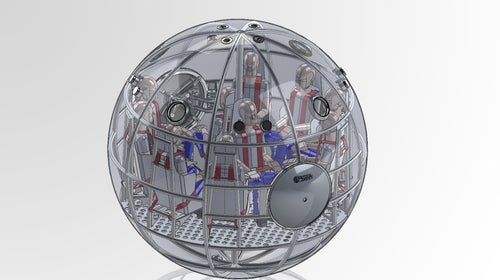

They can hold from two to��ten people, depending on the model, and are made from aircraft-grade aluminum in what’s called a continuous monocoque structure, an interlocking frame of aluminum spars that evenly distribute force, underneath a brightly painted and highly visible aluminum shell. The inner frame can be stationary or mounted on roller balls so it rotates, allowing the passengers to remain upright at all times.��

Inside are a number of race car–style seats with four-point seatbelts, ��facing either outward from the center��or inward around the circumference, depending on the number of chairs. Storage compartments, including food and water tanks, sit beneath the seats. Two watertight hatches open inward to avoid outside obstructions. Being watertight, it’s a highly buoyant vessel, displacing water like a boat does.

“I fell in love with the capsule,” says Bellini. “I’m in good hands.” He selected a three-meter, ten-person version, for which he’ll design his own interior.��

Sharpe got the idea for his capsules after the 2004 Indonesian tsunami. He believes fewer people would have died had some sort of escape pod existed. With his three-man team, which includes a former NOAA director and a Boeing engineer, he brought the idea to fruition in 2011. Companies in Japan that operate in the line of fire for tsunamis��expressed the most interest. But Sharpe hopes the products will be universal—in schools, retirement homes, and private residences, anywhere there is severe weather. The first testing prototypes of the capsules, which range from $12,000 to $20,000, depending on size, were shipped to Tokyo in 2013. Four are in Japan;��two are in the United States. His two-person capsule is now for sale; the others will follow later this year.��

“Right now there’s only horizontal and vertical evacuations,” Sharpe said. “We want to offer a third option: riding it out.”

The company intends to rely on an increasing market for survival equipment as sea level��and the threat of major storms��rise. Sharpe designed the capsules to be tethered to the ground using 20 to 50 meters of steel cable and to withstand��a tsunami or storm surge. Each will have a water tank and a��sophisticated GPS beacon system in case the tether snaps. Survival Capsule advises storing seven to ten days of food in each capsule.��

The product appeals to Bellini because it’s strong enough to survive a storm at sea��or getting crushed between two icebergs. It will rest on top of the ice using either its own weight��or a specially designed stand that will detach if the berg rolls. The circular shape is crucial for avoiding a crushing blow. The capsule will just roll off any incoming mass, and the water will provide an equal and opposite reaction to any force exerted on the capsule. “A multicurved surface is almost uncrushable,” Sharpe said. “If you imagine shooting an arrow at a wooden ball, unless you hit dead center, it’ll ricochet.”

The capsule is strong enough to survive a storm at sea��or getting crushed between two icebergs. It will rest on top of the ice using either its own weight��or a specially designed stand that will detach if the berg rolls.

The basic model ensures survival, but there’s more to life on an iceberg than just surviving. You can add windows, extra space, and other modular additions, even surround sound and color options. “You can trick your crib out all you want,” Sharpe said. And that’s exactly what Bellini plans to do. He doesn’t have a layout yet, but he has hired Italian designer Pietro Santoro to customize his ten-person pod. He will remove the other nine seats for extra room.��

Other than modifications to keep him safe and healthy, the capsule is basic, Bellini said. It will carry 300 to��400 kilograms��of food, a wind generator, solar panels, and an EPIRB beacon so rescuers can find him. He’ll have Wi-Fi to update his team and the public. The layout will consist of a work table, electronic panels, and a bed. “A foldable bed,” Bellini added. “I want to have room to work out.”

Bellini will spend almost all of his time in the capsule with the hatch closed, which will pose major challenges. He’ll have to stay active without venturing out onto a slippery, unstable iceberg. If it flips, he’ll have no time to react. He’s working with a company to develop nanosensors able to detect movement in the iceberg��so he has advance warning of a flip. “Any step away from [the iceberg] will be in unknown territory,” he said. “You want to stretch your body. But then you risk your life.” He fears a lack of activity will dull his ability to stay safe. “I cannot permit myself to get crazy,” he said. “I need to keep my body fit, not for my body, but for my safety.” He is working on a routine of calisthenics that can be done in the capsule,��and he might��install a stationary bike, most likely a .��

Lack of sunlight is another challenge of spending a year in an aluminum sphere. It will be winter in the Arctic, with maybe five hours of light each��day. Bellini and Sharpe are working on a lighting system that will simulate natural light, allowing Bellini to get vitamins and maintain his circadian rhythm.

����������Ծ�’s model is in development, and he expects it to be ready in about a year. He plans to write during his mission��and will bring plenty of nonfiction books, especially psychology.

The capsule won’t ease his isolation, maybe his greatest challenge, but Bellini��remains undaunted:��“It’s the key to the inner part of myself.” The first step is relinquishing control.