In a House by the River

Sixteen years ago, the man who helped raise Megan Michelson was shot to death at a remote kayaking lodge in Northern California. Michelson embarks on a painful search to find out what happened, and why.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

For nearly 50 miles, the road bends with the river—first the South Fork, then the Main Salmon. Cecilville Road was nothing but one lane with a few pullouts in 1991, so locals used CB radios to avoid collisions. I was nine then, and sandwiched between my mom, Evans Phelps, and my stepdad, Jerry Davidson, on the bench seat of Jerry’s white Toyota pickup. “What’s your handle?” Jerry asked, passing me the mike.

“This is Kayaker Nine,” I announced. Jerry was teaching me trucker slang, and Mom laughed. “We’re heading downstream on the South Fork at mile 11. Over and out.”

“You’ve got a future in radio, kid,” Jerry told me, cracking sunflower seeds in his teeth. He cranked up Tom Petty’s “” on a mix tape my mom had made, and we sang along. Jerry was tall and strong, wearing sunglasses attached to a cord around his neck. Mom’s dark, wavy hair hung to her chin, and her legs were lean from cycling.

Somewhere up the road was our cabin on California’s Salmon River, one of the very few undammed rivers in the state and a spot so remote—deep in the 1.7-million-acre —that electricity still doesn’t reach it. The closest town, Forks of Salmon, consists of a post office, a tiny elementary school, a herd of wild ponies, and an oak-shaded picnic table that serves as the local pub. Fewer than 100 people lived out there then, and fewer now: gold miners, pot growers, Native Americans, hippies who come to stay at the nearby Black Bear Commune, and, thanks to the world-class whitewater, a handful of kayakers.

A couple of miles downstream from Forks, Jerry turned left at the wooden sign marking the entrance to Otter Bar Lodge, the whitewater kayak school where he had met my mom. The lodge shared a road with our cabin—a small, wood-framed loft with a gas stove and no walls, perched on a cliff overlooking a quiet bend in the Salmon.

That year, I took a boogie board down a mellow stretch of river, roasted marshmallows, and swam in the ponds while Mom and Jerry kayaked. It was one of the last times that things were really good.

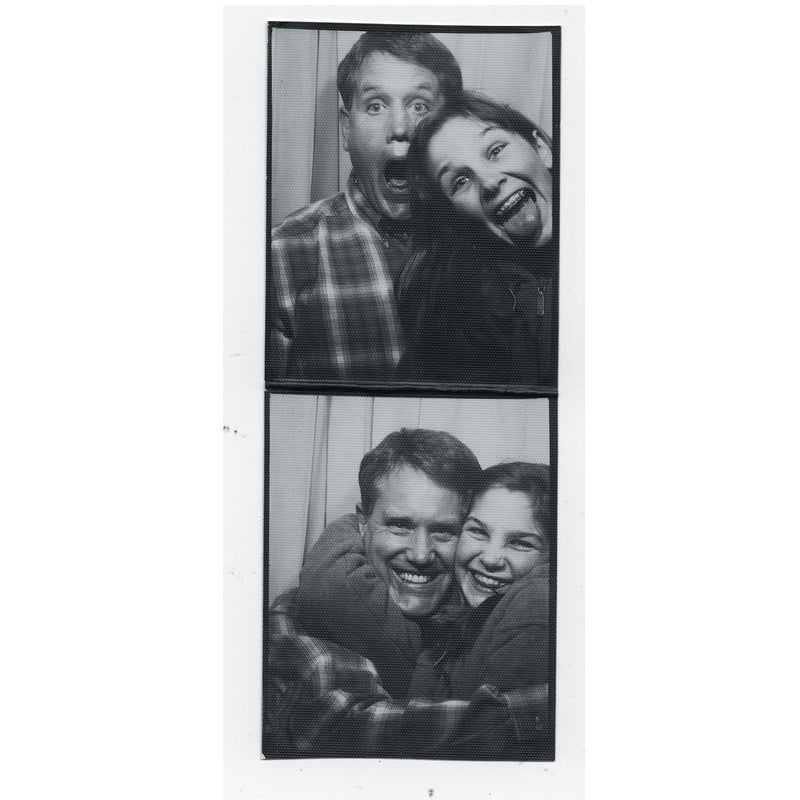

On our first night at the cabin, Jerry and I carved our names into the picnic table out front. Jerry used his middle name, Raymond, which was also his trailer-park alter ego. When he and Mom—married for two years at that point—went on vacation, they used to make home videos pretending to be Marge and Raymond, a redneck couple out for a good time. Our Christmas card that year featured the whole family, including my 15-year-old brother, Miles, and 13-year-old sister, Erin, dressed in rags in front of a dilapidated shed. It read, “Merry Christmas. How was your year?”

It was all an act, of course, but the kind that softens the truth by exaggerating it. You see, Jerry had a violent side that came out when he drank. One minute he’d be playing fetch with our dog, the next he was shattering plates. I only remember snippets of the fights—of him smashing a dresser and hitting Mom in the face with a full Diet Coke can, blackening her eye. Once he got so mad at Miles that my brother ran out of the house and then moved back to Dad’s place a few weeks later.

Jerry had been drinking on February 18, 1995, the night he died just a few hundred feet from our cabin. He was alone there that weekend; my mom and I were skiing in Tahoe. I was 13, old enough to feel the calamity of his death but too young for anyone to entrust me with the details. At the time, Mom told me Jerry had gotten into a fight and that his body had been found in the doorway of the Otter Bar owners’ private residence. The few times I asked for specifics, Mom’s response was short: “You don’t want to know.”

But I’m 28 now, and I do want to know. Jerry was flawed, but he wasn’t a monster. He raised me from age four to 13, and even though his death gave my family a twisted kind of peace, I still loved him. I want to know what happened to him and, more important, why. Over the years, I’ve looked up the stories from the Siskiyou Daily News. The first articles ran the day after the incident:

Jerrold Raymond Davidson, 40, was shot after an argument over a trespassing incident. John Douglas Greiner, 35, was arrested after he called 911 and reported that he had shot Davidson. Greiner reportedly was care-taking [the] property at Otter Bar Lodge. The victim owned the property next door and reportedly spent weekends there.

Another headline appeared 38 days later, when Greiner, who goes by J.D., was released from jail: “Murder Charges Dismissed Against Salmon River Man.”

Last summer, when I went to Mom for answers again, she agreed to talk. We decided there was only one place to do it.

It’s a sticky afternoon in June when we arrive at Otter Bar, two kayaks stacked on the roof of my Subaru. Peter Sturges, the lodge’s owner, is pedaling his mountain bike up the driveway when we pull in. He doesn’t recognize me at first, but he sees my mom in the passenger seat and swings off the saddle.

“That’s Megan, all grown up,” she says.

“Of course,” says Peter. “Welcome. The river is running great right now.”

In her prime, Mom paddled Class V. She’s 60 now, graying and showing the sun and wear in her hands, but still shockingly fit.

The last time I was here was five years ago, but Otter Bar has a timeless gloss to it: a white clapboard lodge surrounded by green lawns, with two small ponds where instructors teach kayak roll sessions. It’s edged by giant firs and a river that still supports healthy salmon runs. It’s a wildly beautiful landscape darkened by the cloud of what happened to my family here.

That night Mom and I set out lawn chairs on the bluff overlooking the river and drink chardonnay from plastic wineglasses. We both know what we’re here to discuss, but there are barriers that must be moved. She’s survived the deaths of a child and a husband, as well as her younger brother to the first AIDS outbreak among San Francisco’s gay community. I think we’re both pondering the sanity of her unloading the weight onto me. Finally she sighs, gulps some wine, and begins to talk.

In 1980, my parents’ third child, a girl named Macey, born two years before me, died of SIDS at three and a half months. I’d known this was an inflection point in their marriage. Afterwards, Mom would go to the basement, where Macey’s baby clothes were stashed, and sob. My dad, Steve Michelson, went back to work, perhaps too quickly, at the San Francisco video-production company he and Mom had started. It was a multi-million-dollar operation that produced national TV programs, commercials, and even segments for the Olympics. “That business was your dad’s mistress,” my mom says.

They tried to save their marriage. My own birth, in 1982, was one attempt to fill the void. They tried in other ways, too. In March 1984, after reading a story in this magazine about a new lodge called , Mom booked a week of kayak lessons for both of them. They returned the following two summers. On their third trip, in June 1986, my dad left Otter Bar early to finalize the sale of their company, and Jerry, a substitute instructor, arrived. He flirtatiously mistook Mom for a former Miss Florida, who was also a guest that week. Mom says there was something electric about their connection. This is the first time she’s told me how it all happened.

Jerry was 31 then and had a square jaw and an athletic build. “Can I share your pillow with you tonight?” he asked her. “I’m a married woman,” she responded, but she still gave him her phone number when he asked for it over milkshakes the next day.

Jerry called Mom at home a few days later and invited her on an overnight trip down the Class III Chili Bar stretch of the South Fork of the American River. She asked a friend to take care of us. I was four, my sister was eight, and my brother was ten. “I just want to have some fun,” she told her friend. She told Dad she was going kayaking but didn’t mention Jerry.

They met by the river, ate pizza, and set up camp. “Are we going to have an affair?” he asked. “I certainly hope so,” she replied. When she returned home at 1 a.m. the following night, Dad asked, “How was the boating?”

A few months later, after 16 years of marriage, my parents got divorced. I barely remember it, but it was a big deal for my brother and sister. Mom moved us from the Bay Area to Nevada City, a sleepy Northern California town known for its proximity to gushing rivers. I spent occasional weekends and holidays with Dad and, oddly enough, he went on to date that former Miss Florida. But what I remember most about that time is Jerry. My earliest memories are of him teaching me to throw a softball and make grilled cheese sandwiches.

And I remember that he made Mom ridiculously happy. Her notes in the margins of an old, weathered copy of A Guide to the Best Whitewater in the State of California, which she gave me, read like diary entries: “January 9, 1987. Middle Fork of the Smith River. Evans’s first adventure into winter boating. I like winter boating, kissing in the eddies and riding bikes for the shuttle. We’re still smiling the same at each other. I love Jerry.”

In 1988, Peter Sturges offered to sell 10 of his 40 acres to his best client—my mom—for $150,000. With some of the proceeds from the sale of the video company, she tells me, she bought the property that she and Jerry named Outer Bar. That she paid for the property always bugged Jerry. Mom had grown up in a world of boarding schools and trips to Aspen. Jerry came from a middle-class family and wanted to pull his weight. So Mom let him design the cabin—without exterior walls, like he wanted—and that seemed to placate him.

They got married in May 1989, and for their honeymoon they bused 14 members of our family to Otter Bar for a week of rafting and kayak lessons. A home movie shows me, at age seven, sitting in a kayak in the pond. “Did you go boating today, Megan?” Jerry asks me. I had rafted that day, clinging to the boat with all my might, but I pretended that I had kayaked. “Yeah, I kayaked,” I said. “How did you handle that big rapid? Straight down the middle?” Jerry joked. “Yeah, straight down the middle,” I giggled.

Then things started to corrode. The fights usually happened late at night. Yelling and loud thuds from their bedroom, followed by unexplained bruises and broken furniture. My mom was mortified when my sister and I would see it. Sometimes she’d apologize to us the next morning.

During one particularly bad fight, Mom threw their wedding album into the fire. I couldn’t stand the sound of their rage, so I walked into their bedroom in the middle of one ferocious war and asked Jerry if he wanted to play cards. That seemed to ground him, at least momentarily. Mom says I always had a calming effect on him.

By 1993 Jerry had undergone knee surgery and quit his job as a physician’s assistant, and he was clearly depressed. He drank more, saw a therapist, and put on weight. One day, I wore my hair down with the top half pulled into a barrette. “I like your hair like that,” Jerry told me. “I want you to wear it like that at my funeral.”

In the fall of 1994, just a few months before his death, Mom finally told him to move out. He packed his things and got a job in Medford, Oregon. After he died, Jerry’s sister found a journal in his apartment, which Mom copied and gave me earlier this summer when I told her I wanted to write about Jerry’s death. One late entry read, “How long can I sit here and not blow my brains out? What’s the reason for being here? Life goes on and I go down, down to the depths of such despair.”

Fortunately for my family, the last time we saw Jerry he was the gentle, sweet man Mom had first met. Two days before he died, Jerry showed up unexpectedly in the middle of the night. He brought Mom two dozen roses for Valentine’s Day and a note that ended, “Let us put all our troubles behind us. The new, improved Jerry wants peace, love, and kindness, especially with you.” The next morning, he drove me to school and gave me a bigger-than-usual hug at the curb of my junior high.

The following week, I cried while putting my hair half up for his funeral.

The morning after our beach-chair chat, Mom and I are floating in a calm eddy near the shore. Just downstream, the Salmon drops into Indian Crossing, a rapid that requires a clutch move to avoid a nasty keeper hole. Keepers are made when the river dumps over a boulder and forms a chaotic vacuum at the bottom. Water, and by extension boats and people, that should be flowing downstream are instead sucked back upstream in an indefinite cycle. Not far below the rapid is the take-out at our porch.

“Go right down the middle,” Mom says. “Just above the hole, brace hard with your right blade and cut left.” Then she arcs into the current with me on her tail. We both run a clean line, maneuvering around the chaos.

After we peel off our wet gear, I walk over to Otter Bar and knock on Peter and Kristy Sturges’s door, which is just next to the lodge where the guests stay. Originally from Rhode Island, Peter moved here in 1972 from Alaska, where he’d been working as a commercial fisherman. Kristy was a local schoolteacher. They got married and bought the property on the Salmon River in the early eighties. They raised their two children here, and their son, Rush, has gone on to become a well-known kayaker and action-sports filmmaker.

Peter, now 61, invites me into their kitchen. For an awkward moment, I pause in the doorway, knowing that this is where Jerry took his last breath. In front of me, there’s an old gas stove and a cluttered countertop. To my left, a staircase leads up to the home office where J.D. placed the 911 call that night. Kristy has found the typed 911 transcript in her filing cabinet and hands it to me. I take a seat on the couch and flip cautiously through the first couple of pages.

J.D.: I have a man in my house that will not leave.

DISPATCHER: Okay, he’s trespassing?

I’ve asked him to leave several times, and he thinks it’s funny. He’s laughing at me. I think he’s maybe slightly intoxicated.

Okay, what is your name, sir?

I’m J.D. Greiner. I’m staying at Otter Bar Lodge.

Okay, and who’s the man?

He’s the next-door neighbor who has assaulted me before.

Peter is leaning over an armchair with the afternoon light filtering through the windows. I stop reading and ask him when things went bad with Jerry. He tells me that Jerry had worked at their doctor’s office in Arcata and they all became friends. J.D., who did odd jobs around Otter Bar, met Mom and Jerry in 1989, when they hired him to do some work around the property.

J.D. and Jerry became pals and occasionally boated together. The first time they quarreled was when they were building the septic system for the cabin. The engineers had screwed up the leach lines, and Jerry angrily blamed it on everyone else around him. J.D. had pulled Mom aside and asked, “Are you going to be OK driving home with him?” She said she’d be fine.

Before the house was built, there was another incident, Peter says. A few kayak instructors camped on our property, later telling Jerry that Peter had told them it was fine. (Peter had in fact instructed them otherwise.) “Jerry called me and he sounded uptight,” recalls Peter. “Jerry said, ‘I hear you’ve been renting out my place.’ He sounded like a completely different person. That was the start of this whole thing. That’s what set Jerry off. I had the feeling that I was going to be dealing with a nightmare for a while.”

Jerry became increasingly upset over an access issue on the property. The ten acres that Mom had bought included the shared driveway that accessed both properties. Peter had an easement, of course, but Jerry would often place large stones along the driveway, marking our property line.

Jerry got confrontational after that, and Peter claims he threatened to bomb the lodge and turn him in to the county for illegal construction projects. J.D. and Jerry were still friends, but that all changed one day a few months before Jerry’s death, when he padlocked the gate at the top of the driveway. Lodge guests had no way of getting in.

J.D. often carried a gun, and that day he had a .357 caliber revolver on him. He fired a shot, either at the lock or at a squirrel, depending on whom you ask. “J.D. is a gun guy,” Peter tells me. “Which isn’t that rare up here.” Jerry heard the shot and became irate, blasting J.D. for having a gun on his property. Then Jerry knocked him to the ground and kicked him.

After our talk, I leave Peter’s house and sit outside on a rock wall to finish reading the 911 transcript alone. A few pages in, Jerry gets on the phone to talk to the dispatcher.

JERRY: This man drove across my property. He fired a weapon at me this past summer.

DISPATCHER: What do you want from J.D. today? I mean why did you come over to his house and knock on the door?

I did not come over to his house.

All right. Are you not—

This is not his property. He’s not on his own property.

Okay, Jerry, why don’t you just hang up the phone and go home then.

Well, I don’t know, this is my property—I have as much right to be in this place. I mean he’s stirred the pot, he’s definitely stirred the pot.

I can’t tell from the written transcript if Jerry is angry or drunk, and the audio file has long been discarded. But Mom remembers listening to it after the incident. “Jerry sounded pretty calm to me,” she says. “I didn’t know how drunk he was until the autopsy came back.” His blood alcohol level was .22 percent, nearly three times the legal driving limit.

Jerry gets off the phone, and the dispatcher talks to J.D. again.

DISPATCHER: We’ve got a unit en route.

J.D.: I’ll just stay on my side of the room and he stays on his. Jerry, leave.

J.D.

Go away, Jerry.

Keep the situation under control.

I’m trying.

Disconnect the phone and go outside until we can get a deputy there.

Ow … ow … He just kicked me in the balls.

J.D., just leave the house. Hang up the phone and seek safety. Go upstairs and lock yourself in a room. Do that, okay?

Leave, Jerry. Ooooooh. He’s on one side of the door, I’m pushing against it [heavy breathing]. Come on, Jerry [heavy breathing].

Then the line goes dead. Nearly two minutes later, J.D. calls 911 again.

J.D.: Oh man. Send a coroner, please.

DISPATCHER: What happened?

He was beating me back.

What do you mean, send a coroner? Mr. Greiner.

I had to shoot him.

By the time I was 14 and in eighth grade, it was just me and Mom in the big empty house in Nevada City. My brother and sister were both in college, so when Mom went away on yet another of her weeklong kayak trips that spring, it was just me. One of my sister’s friends was staying with me, but she used the grocery money to buy beer.

I never told my mom how much her absences upset me. I wrote diary entries about how I felt totally alone in the world, which is probably what every 14-year-old girl feels. But Jerry was dead, and my mom wasn’t around to talk about it. I began shutting her out, giving her the silent treatment even when she was around.

Later that spring, Mom held her annual kayak party. The place was overrun with Toyota trucks, ratty tents, and dirty shirtless guys wearing Tevas. Everyone was drinking beer or some cocktail involving Red Bull. I invited some of my friends, and we wandered in awe as strangers smoked pot on my trampoline and skinny-dipped in the swimming pool. By the time I was 17, my mom’s younger guests began hitting on me and my friends. After one of her epic parties, a drunk twenty-something stumbled into my room and asked for my friend Hilary, who was sleeping over. I kicked him out.

And it wasn’t just the parties. Our house was continuously infested with freeloading boaters who smelled of mold, ate our leftovers, and brought me presents in an effort to seduce my single mother. I hated kayaking—hated how it had torn my family apart and turned my mom from a successful businesswoman into a hard-partying widow who occasionally hucked herself off waterfalls.

The fights usually happened at night. Yelling and loud thuds from their bedroom. During one particularly bad fight, Mom threw their wedding album into the fire.

I became a case study for the effectiveness of reverse psychology in parenting: the more she rebelled, the straighter I became. She smoked weed several times a day; I refused to touch the stuff until my last year in college, when friends finally persuaded me to nibble a pot brownie. Most of all, I refused to let her teach me to kayak.

“After Jerry died,” my mom says now, “the only way I could make it stop was to go kayaking. Because then I had to think about the river and it took my mind off everything else.”

While I was struggling with the loss of Jerry and Mom’s frequent disappearance, she met Dieter King. I was 17. He was some kind of California whitewater pioneer. When he moved in, I packed up my things and lived in the apartment above the garage.

Mom was happier, but this all seemed too familiar. I still can’t bear the sound of even mild argument. Raised voices cause flashbacks to the fights, the broken glass, the house-shaking tremor of Jerry’s body moving toward hers. Dieter seemed like a gentle man—he is—but I didn’t want to risk it. I stayed above the garage until the fall of 2000, when I left for Middlebury College, in Vermont. It was the farthest place I could find from California.

Eventually I did learn to kayak. At Middlebury, I hiked and skied—and met some of the school’s young kayakers, who made the sport seem, well, fun. In 2004, after graduating and moving back to California, I mentioned that I might want to try kayaking. Mom did the only logical thing and signed me up for a class at Otter Bar.

The night of the shooting, J.D. was arrested and charged with first-degree murder. Desperate for help, he called his fishing buddy Eric Bergstrom, a local criminal defense attorney. Bergstrom’s case was so weak—J.D. having confessed to shooting an unarmed acquaintance—that if Peter Sturges hadn’t put up the cash to hire Michael Thamer, a respected private defense attorney who’d moved to the area from Orange County, J.D. would likely be serving a life sentence.

I meet Thamer at Nordheimer Campground, a couple of miles downstream from Otter Bar. He’s wearing canvas pants and a Wilco T-shirt from a 2004 tour. He’s 54, a year younger than Jerry would have been. When he refers to Jerry as my father, I don’t correct him.

“I never met your father,” Thamer says, sitting at a picnic table. “When I met John Greiner for the first time, he was in custody. John is a quiet, reserved, different person. Anyone who wears a gun is a different kind of person. But when you’re a couple hours away from 911 out here, people think they need to protect themselves.”

Thamer tells me that, according to the police report, Jerry went to Nordheimer Campground hours before he was shot, and on his way home he drove his truck into a tree, where it was later found by a sheriff. Earlier that afternoon, Jerry had met up with his friend Bill Wing, an outfitter and early manufacturer of polyurethane rafts, who was leading a group of hemophiliacs down the river. “Jerry didn’t seem drunk when I saw him,” Wing says when I call a few weeks later. “Sure, he was going through some problems. He seemed stressed. But he was as friendly as ever.”

Wing testified before the grand jury—one of the few who defended Jerry—and he still thinks there’s something fishy about how the case played out. “The police didn’t do a very good job investigating,” he says. “To do what J.D. did was way over the top. Jerry was murdered. That’s what I felt.”

According to Thamer, that’s what investigators originally believed, too. “The police came and in a matter of moments they decided what happened,” says Thamer. “Was Jerry armed? No. Were there any visible wounds on Greiner? No. They see that Greiner shot someone between the eyes with a .357 and that the victim is unarmed. So they arrest Greiner for first-degree murder.”

The case was the biggest thing to happen in Siskiyou County in ages. “Rare Slaying Rocks Isolated River Town,” blared the Sacramento Bee. Some reports even likened the trial to the still-recent 1994 O.J. Simpson ordeal. “It totally shocked everybody,” said Gladys Stanshaw, the local postmaster.

Two weeks after the shooting, the headlines got interesting again: “New Evidence Found in Salmon River Case.” I ask Thamer what it was. “This is indelicate,” Thamer says. “Do you really want to hear this?” I nod. None of this has been easy to hear.

Thamer’s investigator, Woody Schamel, found some cranial fluid and blood from Jerry’s head above the door in the Sturgeses’ kitchen, which placed Jerry inside the house. The original investigators had simply noted that his body was in the doorway. Schamel also found an indentation on the kitchen wall where the door had slammed the phone into the drywall—breaking the receiver and disconnecting the first 911 call—which showed that Jerry had forced his way in. Thamer tells me that, under California law, if someone who doesn’t live in your house uses force to get in, it’s legal to kill him if you fear for your own life. Lucky for J.D., Thamer proved that Jerry had crossed the magic line.

A handful of witnesses testified before the grand jury, including Peter, my mom, and Bill Wing. Mom says she was ready to defend Jerry on the witness stand, but then she learned how intoxicated he’d been when he died. In the hearing, Thamer asked her whether Jerry was suicidal and wanted this to happen. “I told them Jerry didn’t do this on purpose,” she says. “He wouldn’t have done that. But in some ways, I think he did want to die.”

Thamer presented the evidence they’d found at Peter’s house, as well as a few other damning details: Jerry’s police record contained incidents of threats and battery; he’d stopped taking his antidepressants; he’d driven his truck off the road that night; and of course, there was the 911 call. A day and a half later and less than two months after the shooting, the grand jury decided that J.D. had acted in self-defense.

It’s my last day at the Salmon, and there’s one person left on my list—the only man who knows what happened in those two minutes between 911 calls.

J.D. isn’t in the phone book, he doesn’t have an e-mail address, and Google shows no record of him. But Peter makes a few calls and sends me to T&T Construction, in the town of Orleans, about 20 miles downstream from Forks of Salmon. During the drive, I nervously rehearse what I’m going to say. “Hi, I’m Megan. You killed my stepfather. Got a minute to chat?” I consider turning back but don’t. When I ask for J.D., the man behind the counter points me toward the mill yard out back.

When I spot him, he’s hunched over a saw, guiding planks of redwood across a whirring circular blade. He’s five-nine, maybe 160 pounds, wearing Levi’s, work boots, and a T-shirt. He has a full beard and long gray hair that sticks out the back of his baseball cap. He’s 51 now, and the sun and labor have left their marks on him.

Once J.D. spots me, he shuts down the saw and walks over. It turns out Peter called to tell him I might show up.

“Hi. Sorry to interrupt. Are you J.D.?” I ask.

“It’s been a long time since I’ve seen you,” he says.

“I must have been too young,” I say, embarrassed that I don’t remember. “Do you have a minute?”

He nods, pauses, and offers: “I think the man your mom first met on the Salmon River is a different person than he was at the end.”

“Are you willing to talk about it?”

He nods again and we sit on a sap-covered log. I don’t know where to begin, so, thankfully, J.D. takes over. Once he starts talking, he doesn’t stop for a long time. He’s not the reclusive man people have made him out to be. He’s talking about how he and Jerry were friends once, how they used to paddle together, but there’s really only one story that I’ve been waiting more than 15 years to hear.

“That night in February …”

“I was just sitting down to eat a bowl of ice cream and there was a thud at the door. And there’s Jerry. He has this look on his face, like there’s something up. I was talking to him in a normal voice, and he starts ranting and raving about me doing this and that. And I say, ‘None of this is true. You’ve got to leave.’ And he says he doesn’t have to leave. So I walk upstairs and grab the cordless phone and punch 911. The look on his face when I called 911 was like ‘You’re calling the cops on me?’ And then he says real quiet, ‘You’re dead.'”

J.D.’s recollection matches the transcript, but then he gets to the part where the phone gets crushed behind the kitchen door.

“Jerry kicks the door so it jams my hand back. I can hear the screen door breaking off the hinges. I’m like ‘Jerry, come on. You already hit me, and now you’re breaking Peter’s door. This is enough.’ He has this real demon-looking face. The phone is jammed between the door and the drywall. I back up into the kitchen, where I left my .357 on the countertop, in a holster. So I pick up the gun, flick it open with my thumb, and I take the speed loader—put it in, twist, lock, load. And I’ve got it down like this.”

J.D. holds his thumb and forefinger like a gun near his waist. “And Jerry goes, ‘Oh, you got your gun.’ And I say, ‘Yeah, and you just saw me load it. I’m through, Jerry; just leave.’ And he looks at me right in the face and goes, ‘I’m going to shove it up your ass.’ And he starts stepping forward. So I let one go and caught him right up in the left part of the forehead. He did a 180, took a step, and sat down.”

I’m feeling dizzy, and I can barely comprehend the fact that, for my benefit, J.D. is getting down on the ground to act out Jerry’s 190-pound body falling—his left leg underneath him and his upper body collapsing forward. I feel a sense of curdling sadness settle over me. This is how Jerry left the world: not gracefully or heroically but with a hollow-point smashing through his head. No fairy dust or white light. Just the cold tile of Peter’s kitchen floor.

I hate J.D. for telling me this. I hate him for pulling the trigger instead of running away. I write the word coward in my notebook next to his name. I can’t stand how small and worn out he looks, the smell of sawdust and sweat coming off his skin. And I can feel a sudden urge to leave and speed down the twisting roads.

But I’ve seen for myself how a dozen or so beers could transform Jerry from a loving father to a screaming, baseball-bat-swinging maniac. Mom would have killed him herself if he’d ever touched us.

Once J.D. is done talking, I hammer out a choppy goodbye—”Thanks,” I say, awkwardly and regrettably—and run for my car.

Mom and I don drytops, helmets, life jackets, and spray skirts at the put-in of a Class IV section called Butler, on the Salmon’s main canyon. The granite walls sling upward on both sides of the river.

“I paddled this stretch the day I met Jerry,” Mom tells me. “It’s one of my favorites.”

The canyon walls have been polished smooth over the centuries, and the river, now joined by two tributaries, flows heavier than it did upstream on the South Fork. I tell her that worrying about the rapids feels joyfully distracting. She says she understands, and I feel some of the old bitterness wash away. Coming out here, I’d kind of hoped to vindicate the man who raised me, but instead I feel a new sense of understanding for my mom, who did the best she could no matter how life and the people in it failed her.

Mom is happy now. She and Dieter have been together for more than ten years, and she owns a successful motel in Nevada City.

Later in the summer, a few weeks after our return from the Salmon, I will find a note I once wrote, crammed into a box at the top of a closet. It’s dated February 20, 1995, two days after Jerry’s death: “I pray each day that I will not forget the happy times. Jerry must stay in my mind always. I write this down privately in order to remember how I feel and how much I love him.”

During the drive, I nervously rehearse what I’m going to say. “Hi, I’m Megan. You killed my step-father. Got a minute to chat?”

It’s like a message my 13-year-old self wrote to my 28-year-old self. Don’t forget: who you are now is partly who Jerry helped you become: writer, kayaker, cyclist, triathlete, telemark skier. When he wasn’t destroying himself and the people he loved, Jerry was the ultimate adventure dad.

Back on the river, things flow as they should between mother and daughter. We’re finally headed downstream again. Mom gives me tips on getting through each rapid—pointing out the nasty holes and the sketchy eddy lines. She is part guide, part mentor, part friend. At the take-out, we change and she offers me a beer from the cooler in the car.

The cabin has walls now. Soon after Jerry died, Mom decided to add them to block the wind and rain. On my last night there, she tells me how, when the walls were being built, she put a small box between the wood and the insulation near the front door. Inside, she placed a handful of Jerry’s ashes, a photo of the two of them, and a note written on lined yellow paper. “I put the box there for the people who decide to update this house 100 years from now,” she says. “Then they’ll know who built this house and everything that went along with it.”

I ask my mom if I can see the box, somehow break into the wall and read the letter and see his ashes. “No,” she says. “It’s not really for you. It’s for the next generation to discover.”