For the past two summers, I’ve worked as one of four women on a U.S. Forest Service hotshot crew near Mount��Hood, Oregon. Early last season, while we waited for a fire assignment, I was tasked with building shelves for 40 old crew photos dating back to the mid-1970s. As I took the pictures off the wall, I noticed a few women in��early images. With their clothes and faces covered in ash, they were hardly distinguishable from their male colleagues, besides the occasional messy braid or ponytail. Though decades separated us, their expressions were familiar to me—their eyes��creased with joy and exhaustion. I could see myself in them��and in the tired, genuine smiles that can only result from��days of hard work.

When the 2019 fire season ended, I tracked down some of these women and their peers, the first women to hold positions on hotshot crews in California and the Pacific Northwest. Over phone calls and cups of coffee, I asked them to share their memories of the job that united us, despite the decades that separated our time doing it. They laughed as they recalled hard shifts and recounted their experiences working in a field that, prior to 1975, due to few women applying and many supervisors not hiring women, had attracted only men.��

They shared stories of blatant sexism and harassment, but they also shared their triumphs.��I learned about the days that made them feel alive, about the fires and shifts they’ll never forget, about policies they changed for the women who came after them.

Sue Husari

Lassen Hotshot Crew Member, 1976–1977

The two seasons Sue Husari spent as a hotshot led to a 45-year��career in fire management. In 2012, she retired from the NPS Pacific Northwest Region, where she served as the regional fire management officer. “You don’t have many more opportunities to just watch fire burn like you do on hotshot crews, and there’s no better way to learn about fire. It helped me form the basis for my understanding of fire ecology,” she��says.��

Husari was hired to��Lassen, a hotshot crew in Northern California, in 1976. She was the first woman on the crew��and one of the first women on a hotshot crew in the state. “I still don’t know why they decided to hire a woman. It was very unusual,” she says. Still, her experience on Lassen was overwhelmingly positive: Husari��says she wasn’t treated differently than her male colleagues, except that her coworkers often looked out for her, particularly because she was just 21 when she was hired.��

“The guys were a little bit older��and very protective of me,” she says. “Many of them had been in the Vietnam War and had moved up to the mountains when they came home. For them, it was just a job, and they were there, and they liked it, and I was also there, and that was it.”

While she was new to the world of wildland fire, it didn’t take long for Husari to realize that she was well suited for the rigors of hotshotting. “My best attribute for firefighting was endurance, and I think that’s common for most women who do this,” she says, noting that she’d spent her youth and teenage years backpacking in the Sierra Nevada��with her dad. “I wasn’t a natural athlete, but I could hike, I could carry heavy stuff, and I was familiar with the outdoors, so I was good at it.”

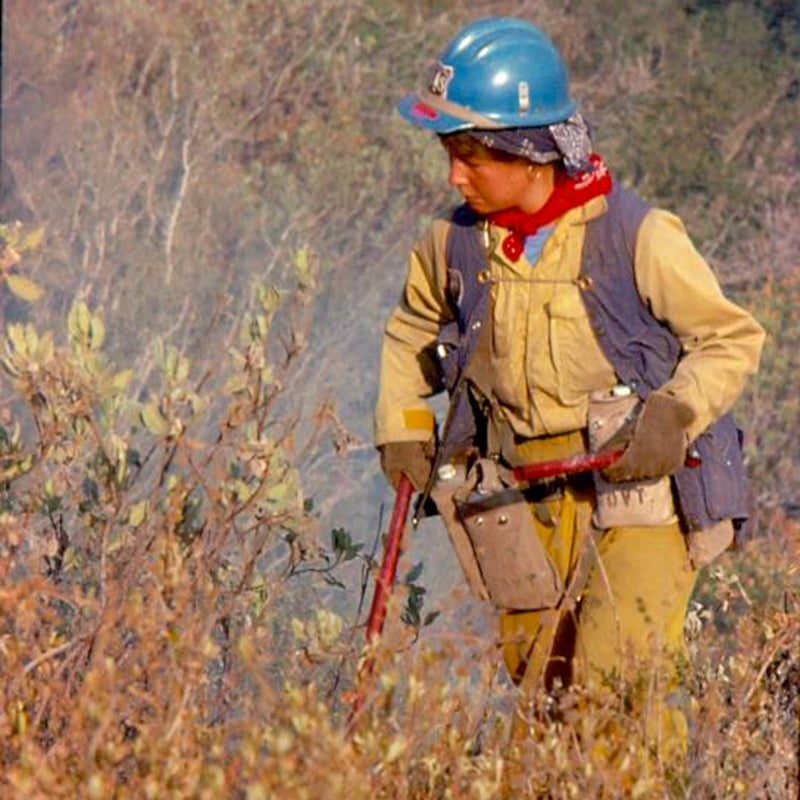

Kimberly Brandel��

Zigzag Hotshot Crew Member and Squad Boss, 1976–1980

Kimberly Brandel was a hotshot from 1976 to 1980, five seasons in a time when it was still rare to hire a woman, let alone retain her for more than a season or two. She was the first woman��hired fulltime��by Zigzag—though some women had filled in for an assignment or two during��earlier seasons—and was one of the first women to work on a hotshot crew in the Pacific Northwest.��

Brandel is refreshingly honest about her first year working as a hotshot��in a world that was still a bit unsure about having women around. “It was the attitude of a lot of men that I didn’t belong there, and that I was never going to be part of the group because they didn’t think I belonged there,” she says.��

A gradual cultural shift in the Forest Service soon contributed to more women being hired to the crew. Even still, it took years to change the perception that women on hotshot crews were tokens—or only there to fill a quota.��“When I started in fire, fire crews were like a pie cut into 20 pieces, and only one piece of that pie was allocated for women. The rest were allocated for men,” Brandel says.��

But the long-held assertion that women didn’t belong on hotshot crews changed dramatically in Brandel’s time with Zigzag.��Another woman came to the crew in 1977, and Brandel eventually moved into a role as squad boss, a leadership position that is still rarely occupied by women. By the time Brandel left to pursue a master’s in fire ecology in 1980, four women appeared in the crew photo, and eight just two years later.��

“Whether you’re in a leadership role or in a capacity to provide input, I think being a woman brings a different perspective,” she says.

Brandel eventually retired from the Forest Service in 2010. Her years of hotshotting greatly influenced��not just her career in fire, but her life in general. “I was always very determined, but I think being a hotshot��made me more determined,” she says. “It gave me more self-confidence��that I could indeed do anything that I set out to do.”

Danah Feldman

Baker River Hotshots, First Female Hotshot Squad Boss (1976–1979, 1982–1984)

“To be honest, if someone had told me what this whole fire thing would require, I would have said, ‘Oh, I can’t do that,’” says Danah Feldman, who worked for the Baker River Hotshots in the late 1970s and early 1980s. “I had no idea what I was getting into, and I wouldn’t have done it if I had. But what fire taught me over and over and over again was how to throw myself into things and just start flapping my wings somewhere along the line.”

Feldman admits she stumbled into the fire world out of a combination of naiveté and curiosity. But within just a season, she had carved out a place for herself on the crew��and made a lasting impression on her team’s leadership.��

“After my first season on the crew, my superintendent, Joe King, gave me a performance award, and I told him I was really surprised,” Feldman says. “And he said, ‘I am, too.��I never thought I’d give a performance award to a woman.’”��

In the mid-1970s, King’s supervisors told him��to hire more women to fill quotas, though they were still skeptical of his ability to retain those women, assuming they’d either quit or be fired soon after starting work. As the first woman King hired to the crew, Feldman vastly exceeded expectations and forever changed—at least on Baker River—how female firefighters and hotshots were viewed by the wildland fire world.��

“[King]��told me that he would never have a fire crew without women on it again,” Feldman��says.��

Feldman fought fire through her late twenties and early thirties��and went on to use her wages to pay for a graduate degree in psychology.��

“I loved the intensity of the work, but what I valued the most about fire was what it taught me about myself,”��she says. “Fire was an essential vehicle for learning how to believe in myself and discover my strength. It forced me, truly, to go beyond what I thought was possible for myself, to raise the bar.”

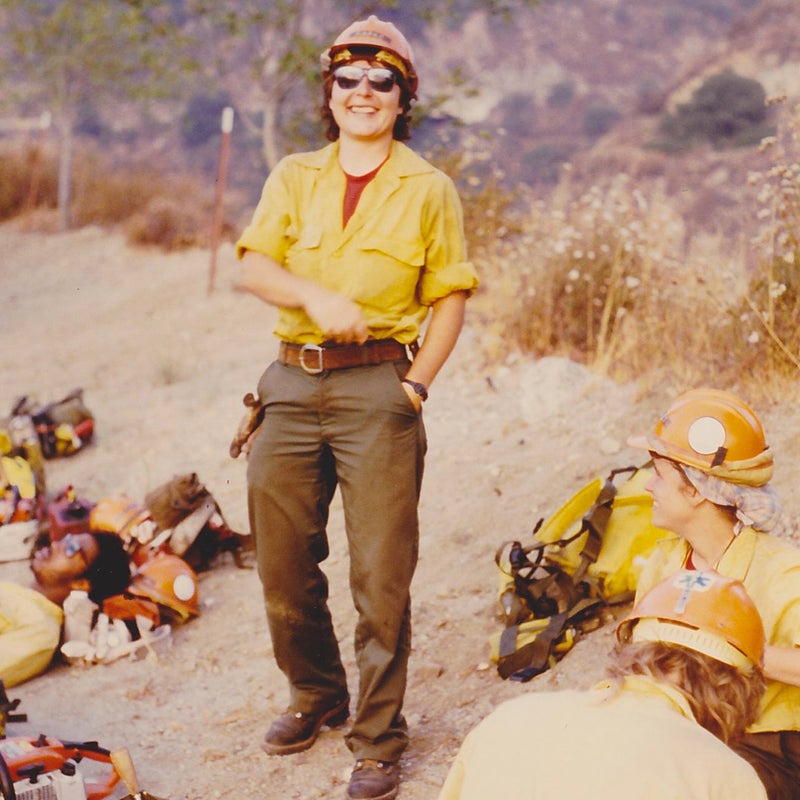

Gina Papke

Zigzag Hotshot Superintendent, 1991–2000

Gina Papke is something of a legend in the fire world. Ask anyone who was on her crew in the 1990s, and they’ll probably tell you that working for Papke made them tough. She had a reputation for pushing her crew members far beyond what they thought they were capable of, whether through long shifts, difficult hikes, or tough assignments in challenging terrain.��

After beginning her career with the Mount Hood National Forest–based��Zigzag Hotshots in 1983, Papke went on to become the country’s first permanent female hotshot superintendent (the highest position on a hotshot crew) in 1991. Only 11 women have since held that position, compared to more than 700 men since hotshot crews were first established in the 1940s—meaning just over 1 percent of superintendent positions on the country’s 110 hotshot crews have been filled by a woman.��

Papke was known for being radically inclusive in her hiring.��She made a concerted effort to continue Zigzag’s long history of seeing the value in including women and other marginalized��people on the crew. Long before such practices were being utilized on other crews around the country, Papke was regularly hiring four to six women to round out her 20-person crew, and up to eight women when there was an influx of good applicants. Even today, it’s rare to find hotshot crews with more than two or three women.

“Women sought me because I was the only female hotshot superintendent, and we were known to be a good crew,” she says. “For me, it was just giving them an opportunity to see what they could do with themselves. Women underestimate themselves, but I knew they’d do well.”