AFTER MORE THAN THREE and a half hours in the deer blind, gazing silently over acres of auburn forest and dried brush and gashes of mud as black as the Mississippi night, the only sign of wildlife we'd seen all afternoon was a plump blue jay nesting under a bush. The wind was picking up and the temperature was dropping. We knew it wouldn't be long before we'd have to call it a day.

Donnell Adair, the 23-year-old former high school football player I was sharing the small wooden blind with, snapped a quick scenery shot with his phone. “You gotta be careful,” he said in the hushed tones men use in blinds. “As soon as you're looking down, sending a picture to your girl, that's when your deer pops up.”

He sent the picture. Still no deer.

Donnell made the same trip last year but never got a chance to shoot his gun. He was hoping to avoid the same fate this year. As the sun began to set, he looked disappointed. It was the week before Christmas and we were in Louise, a small town in the heart of the flat, alluvial, portion of northwest Mississippi known as the Delta. I was on a hunting trip with Donnell and his father, Donny Adair, the founder and president of the African American Hunting Association, a Portland, OregonÔÇôbased group that promotes participation in outdoor sports through a Web site and a small-budget TV show. Every winter, Donny and Donnell fly from Oregon to Mississippi to see Donny's in-laws, get together with other black outdoorsmen, and hunt the magnificent whitetail bucks that grow wide and tall in the soybean fields and backwoods down here.

The Adairs want you to know that, yes, black people in America do hunt, though they can seem as rare in the hook-and-bullet world as they do on ski slopes. Though African Americans make up nearly 13 percent of the U.S. population, they account for only 2 percent of American hunters.

Donny wants to change all that. A jovial, bespectacled municipal-diversity coordinator with a magnetic personality, he feels passionately that hunting could help fix some of the problems in the African-American community. “If kids are in the woods with their fathers,” he says, “they aren't running in the streets, dealing drugs, getting into trouble.”

He also thinks marketing the outdoor life to minorities could be a very lucrative businessÔÇö”a growth industry,” he likes to call it. Always ready to promote his cause, Donny offered to show me a classic hunting experience in the place he calls his adopted home. Earlier that day, at a greasy-spoon caf├ę in nearby Anguilla, we got together for lunch with our unofficial guide for the week, Darnell Berry, a self-described “grizzly bear of a man” with a hearty preacher's voice. He's one of the members of the local hunting club. Over purple soda and a plate of deep-fried chicken gizzards, Darnell said he was confident Donny and Donnell would soon know the joy of harvesting a Mississippi buck. He'd seen plenty frolicking across his property recently.

“They're movin' through!” Darnell proclaimed. “Another fella I know just got a nine-pointer. Beautiful animal.”

Darnell led us toward the club's “lodge,” which is situated on a muddy road in a fairly remote part of the state. To get here, I'd flown in to the nearest major airport, about 100 miles away in Jackson, then driven west on U.S. 80 for a stretch and turned north before hitting the Mississippi River town of Vicksburg, passing through counties whose names sounded Faulknerian: Yazoo, Issa┬şquena, Sharkey. I crossed a section of the Delta National Forest, took unpaved farm roads for about five miles, past gray cypress trees that seemed to climb out of the swamp, and looked for a small clearing with a tiny shed and a propane grill. The patch of land belongs to the Beaver Dam Hunting Club and serves as base camp for hunts in nearby public forests.

The six or so African-American men who founded the club are old-school southern outdoorsmen who can shoot, string up, skin, and butcher a deer before lunch. During last year's trip, as Donny was wrestling his foot out of some mud, Darnell took down a thick eight-point buck at 250 yards, in the rain. Here, when a member of the group kills a deer, everyone celebrates. Five or six men might pile into the back of a pickup and drive around town, showing it off. That night someone makes deer stew and brings it up to the clubhouse for a feast. To get to our stand, Donnell and I rode on the back of a four-wheeler for a mile or so, ducking thorny branches as it splashed through chilly mud puddles. All afternoon we sat 20 feet above the ground, in a stand made of warped plywood and sliding windows taken off an old school bus. We stayed perfectly still, listening for the crunching of leaves. We watched the waves of brush, the trail along the tree line, a patch of bright winter-green grass in the clearing.

Nothing. “That's why they call it hunting,” Donnell said, “and not shooting.”

DONNY ADAIRÔÇöA 60-YEAR-OLD man with diabetes, living in the largest city in OregonÔÇömight seem like an unlikely champion for African Americans in the outdoors. But when he's not at work or with his wife and kids or doing play-by-play for Jefferson High School basketball games, Donny is fishing. Or hunting. Or talking about hunting and fishing.

When Donny goes to expositions and trade shows around the country, he says he's generally one of only two or three African Americans in attendance. Sometimes he's the only one. “It can be a little lonely walking around for six hours and not seeing a face that looks like yours,” he says. “It starts with kids. Not enough boys and girls in the African-American community grow up learning to hunt and fish, taking hunter-safety classes, enjoying the pleasures of the outdoors.”

Donny didn't grow up hunting, either. As a boy, he occasionally went fishing with his grandfather and uncle, but for most of his life he only dreamed. When he married Linda Faye ChocolateÔÇöthe daughter of a southern hunter who took Donny into the foldÔÇöhe quickly grew to love the time he spent trekking through the mud, the gratification of procuring food for his family, the special way men feel when they hunt together.

“It dawned on me that a lot of good could come from black folks going out into the woods,” he says. “You're bonding with your friends and family. You learn to respect the power of a gun. It's also a tradition. A lot of African Americans, especially in the South, have been hunting for food since they got here, before the Civil War.”

There are a number of reasons more African Americans don't hunt today, but, says Donny, it mainly comes down to land access. “In most places,” he explains, “black people just don't have a place to go hunting or fishing.”

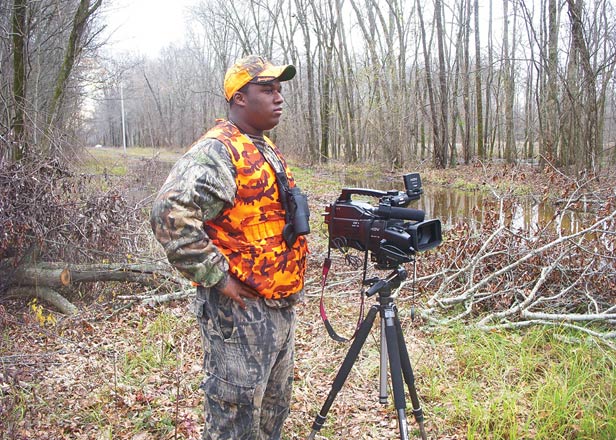

Donny wanted to make sure the outdoors were part of his sons' lives. He took several hunter-safety and master-hunter classes. When Donnell was six, he got to shoot one of his father's guns. By age eight, Donny's other son, Kenny, was a decent fisherman. In 2008, Donny started the African American Hunting Association. Later that year, he bought a hi-def camcorder, asked his sons to help film and a friend to help edit, and started producing a labor of love called The African American Hunting Association Outdoor Show.

For each episode, Donny and Donnell, and sometimes Kenny, travel somewhere new to hunt or fish, often in the Northwest. In one episode, they hunt pheasants in western Oregon. In an episode coming out this fall, they hunt waterfowl around the Willamette River Valley. Right now, the only place to see the show is , but Donny says he's in negotiations with Comcast to broadcast it regionally. He's also working to get sponsors.

Odds are that Donny Adair will never become Oprah in camo, but it would be nice if more people got a chance to see his spirited, smiling face. The opening credits feature Donny's very recognizable silhouette grooving in front of a snowy cabin. The theme song, written and performed by Kenny, is a rap with these lyrics:

It's The African American Hunting Show!

Takin' back the tools that we were given befo'.

It's The African American Hunting Show!

Goin' back to the woods with guns, rods,

and bows!

So let's go! Let's go!

The highlight of season one was the Mississippi trip. In addition to hunting, Donnell interviewed his grandfather, Percy Chocolate. Percy has lived around northwestern Mississippi his entire life, working up until recently as a laborer on a huge Delta farm. He has a first-grade education and has never had a driver's license. From his early twenties on, he fed his wife and three daughters with his rifle. If it wasn't a deer he brought home, it was a rabbit or a squirrel or a fat raccoon.

On our first morning, over a breakfast of eggs, bacon, biscuits, and grits at the home of Donny's sister-in-law, Percy told Donnell and me what it was like for a black man to hunt in those parts 60 years ago: risky. He didn't own land, obviously, so he poached. If the game warden had ever caught him, he would've gotten a trip to jail and a serious beating, and his gun would've been confiscated.

Percy said he would go out only at night, taking the bulbs out of his taillights so the game warden couldn't see him braking. Sometimes he'd be walking with a doe over his shoulder and hear the warden's truck. He'd throw the deer in the ditch and lie on top. “Those white bellies are bright as a piece of paper at night,” he said, adjusting his worn Dallas Cowboys cap and looking off. “Sometimes I could feel the gravel kicked up from the truck tires on my back as he drove on past me.”

It was a cold morning. Sitting, rubbing his hands together in front of a propane heater, the old man was imagining himself stepping through the muck, his eyes scouring the landscape for prey. But he has gout now, and his feet can't take being out in the cold.

“I could still pop it,” he says, referring to his legendary aim. “I could still get that buck. One shot. That's all it'd take.”

FOR OUR SECOND try at a deer, Donny, Donnell, and I woke up at 4:30 and drove through the misty darkness to a piece of Darnell Berry's land, near Anguilla. Most properties along the way had signs made of rotted wooden pallets and rusted oil drums. Some read, POSTED: NO TRESPASSING.

Donny parked his rented Ford Focus at the edge of a muddy bean field. We slogged across, a few hundred yards, and waited quietly as the morning sun lit up the sky. Donnell had decided he wasn't going to be choosy about his deer. He wanted the celebration, the pride of feeding his loved ones with his rifle, just like his grandfather.

“It doesn't have to be a buck,” he said. “I'll take a doe. I don't have to have horns.” But for hours, as the sun arced ever higher, warming the loamy, wet air, we didn't see a single deer.

We did see some white hunters driving by in two hunting-customized golf carts. Each had special mud tires, a large brush guard on the front, and an extended bed built to hold a pile of deer carcasses. They nodded as they passed.

This is not unfriendly country, but these counties, which produced blues icons like Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson, have a history of dark and often violent race relations. It's a region where plantation lifeÔÇöfollowed by sharecropper lifeÔÇöpersisted for 150 years, leaving a residue on every aspect of existence.

In many of these little towns, there are old, white two-story houses with remnants of slave quarters still standing out back. The history lingers in the way white hunters and black hunters don't speak to each other much at the burger joints in town. People get along OK, but there are still two separate worlds here.

As the old traditions slowly crumbled, so did the thriving agriculture business, the lifeblood of the Delta economy. Now this is one of the poorest parts of the country. The farther you get from the quaint grocery stores and town squares, the more you see dogs running in the streets, homes cobbled together from pieces of corrugated steel and salvaged wood, families living in shacks 15 feet from the edge of a swamp.

Hard times often breed community, of course, and that's certainly true for the hunters Donny knows. That night, he made his “world-class chicken vegetable soup.” In a giant pot, he brewed an olfactory-tingling concoction that could warm an entire adult body within seconds. We brought the pot up to the Redbone Cafe, a modest building in the middle of a town called Cary, with unfinished walls, a front door that sticks, and a slanting pool table.

Donny started dishing out bowls to the handful of men sitting at the bar, talking about the improbable run of the New Orleans Saints. Then phone calls were made. Within half an hour, there was a line of muddy pickup trucks parked out front. Everyone had one or two cold cans of Budweiser (except Donny, who sipped juice), and someone put on Keith Sweat's greatest hits. Soon, some of the men called women they knew and there was dancing around the pool table. An hour later, the giant pot was empty and Donnell was listening to hunting stories from the local men. Donny sat behind the homemade wooden bar, cleaning off a few drops of spilled soup. He nodded at the crowd dancing and sharing beers, the smiling faces.

“This is what it's all about,” he told me. “People, the community, getting together. You don't even need a reason. This is the best way to get through life. It's how people survive when things get hard. You celebrate whatever you can, even if it's just my delicious chicken soup.”

THE NEXT MORNING, Donny interviewed me for his show, Donnell pointing the camera while Donny asked me what I thought of everything we'd done. It's funny: For the entire trip, I was the only white guy in a group of African Americans and there was never an awkward momentÔÇöuntil I was interviewed on camera. Even now, I'm not sure what I said as I nervously stammered and rambled on. Afterwards, Donnell told me not to worry. “We'll fix it all with Hollywood magic,” he said.

Donny is only a few years away from retirement, and he'd like to promote his cause full-time someday. In the meantime, he likes to look at Donnell, a college graduate, dressed in camouflage, rifle in hand, anxious to get a deer. “He's the future of America,” Donny told me.

Of course, in places like Mississippi, regardless of race, hunting is a timeless way of life. In the isolated wooden thickets, in the corners of the soggy cotton fields, at the end of the long, bumpy roads. The men here will find a spot to look over the land. They will sit quietly with a gun. They will wait. And life will be OK.

On this trip, Donny and Donnell didn't kill a deer. We saw plenty as we drove around, but there never was one on display during a hunt. In the end, Donnell was undaunted. “It would be nice, but I'm not gonna get too down about it,” he told me. “I've got plenty of years of hunting ahead.”