The ‘Into the Wild’ Bus Was a Pilgrimage Site in the Wilderness. Can It Hold Up in a Museum?

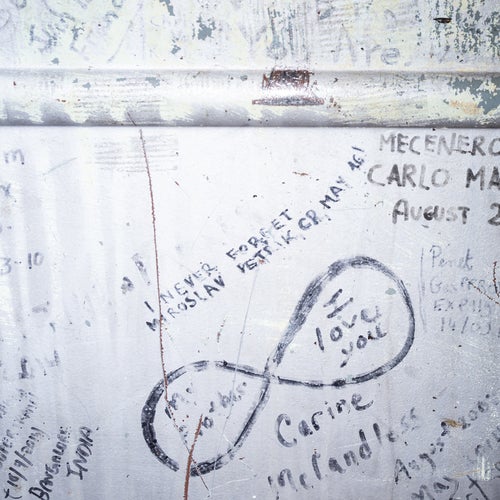

The rusty coach where Chris McCandless spent his final days captured the imagination of people all over the world and inspired hundreds of seekers to make dangerous treks to reach it. Now a dedicated team of curators in Alaska have given it new life as a fascinating exhibit—one that tells the story not just of McCandless, but of modern Alaska.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

On June 18, 2020, Carine McCandless got a call from Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources. Corri Feige, the commissioner at the time, wanted to give her a heads-up: the abandoned bus where Carine’s brother, Chris, had briefly lived and then died was at that moment dangling in midair below a Chinook helicopter, on its way to a flatbed trailer and then to storage in a government facility. The bus made famous by Into the Wild was finally being hauled out.

Carine didn’t have a clue that this might be coming, but she wasn’t entirely surprised. The bus, which sat roughly 20 miles down a rough 4×4 trail from the nearest highway, had been a source of concern to Alaskan authorities for years. Too many visitors, inspired by her brother’s story, had gotten into trouble while attempting to visit the site; too many formal and informal rescues had been necessary. In the previous decade, in separate incidents, two young women died on their treks. Both drowned while attempting to cross the cold, fast-moving Teklanika—the same river that had barred Chris, who was 24 when he died, from retreating to the highway as his food supply ran out.

In the eerily quiet early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, it seemed that someone in the local government had decided that now was the time to remove the temptation of the bus for good.

Carine understood why she hadn’t been given more warning. “The commissioner didn’t know me,” she says. “She didn’t know if I was going to contact a bunch of people and tell them to go surround the bus and sing ‘Kumbaya.’ ” Carine wouldn’t have done that, but she didn’t blame the state for holding its cards close.

The commissioner let her know that the department intended to wait a few days to announce the removal so the family could digest it privately. But even in the relative emptiness of rural Alaska news travels fast, and a famous bus in flight is hard to miss. As the two women talked, Carine’s phone began to ping. And ping. Text messages and social media notifications poured in—an experience shared by other people with a connection to the story. (A short while later, Eddie Vedder, the Pearl Jam front man who created the haunting for the 2007 movie version of Into the Wild, told Carine: “My phone hasn’t blown up this fast since the Cubbies won the World Series!”) Even before Carine checked any of those messages, she had a feeling that the news was out.

Sure enough, a resident of the Healy area, Melanie Hall, had gone for a walk on Stampede Road—the paved portion of the historic overland trail that leads to where the bus sat for 60 years—when she spotted a helicopter with an enormous load. That looks like a bus, she thought as it flew closer, and moments later she knew: it was the bus. By the time Hall made it to a nearby gravel pit where the Chinook set the large vehicle down, another neighbor had arrived, and so had the borough mayor. As the bus was loaded onto a long trailer, Hall snapped photos she later posted on Facebook. A friend reposted them, and from there the pictures were shared and shared. The images went viral, and the state government began fielding media inquiries about the removal.

The Department of Natural Resources didn’t have much to say at first, except that the bus was being moved to an undisclosed location, its long-term fate also under wraps. Feige, the commissioner who’d contacted Carine, issued a statement. “We encourage people to enjoy Alaska’s wild areas safely, and we understand the hold this bus has had on the popular imagination,” it said. “However, this is an abandoned and deteriorating vehicle that was requiring dangerous and costly rescue efforts, but more importantly, was costing some visitors their lives. I’m glad we found a safe, respectful and economical solution to this situation.”

That night as I packed for a canoe trip, I scrambled to put together a news item for ���ϳԹ��� Online. “There’s something strange and bittersweet about knowing the story is over now,” I wrote.

But I was wrong. A new chapter in the long, layered story of Bus 142 had just begun.