ONCE UPON A TIME NOT SO LONG AGO, in a gold-mining town in the foothills of the Sierra mountains, an unlucky baby was born. It was hard for the doctors to tell that the baby was unlucky, because everything about him looked fine. He had blond hair and sumo-wrestler thighs and catlike blue eyes that crinkled into slits when he smiled. But this baby was unlucky because he was born with something extra in his blood, a chemical called meth-amphetamine. The doctors were not optimistic. They predicted the baby would grow up small and skinny, that he would probably have trouble learning things, and maybe worse.

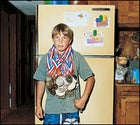

Lucky guy: Roger at home in Placerville, California, weighed down by 89 of his snowboarding medal

Lucky guy: Roger at home in Placerville, California, weighed down by 89 of his snowboarding medal Sky’s the limit: Trampoline action in Roger’s backyard

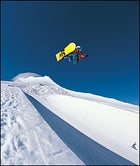

Sky’s the limit: Trampoline action in Roger’s backyard High on the slopes of Oregon’s Mount Hood

High on the slopes of Oregon’s Mount Hood Wacth this! Roger cavorting in the family garden

Wacth this! Roger cavorting in the family garden Roger at eighteen months

Roger at eighteen months In the Sierra, age six

In the Sierra, age six Sporting a mohawk at seven

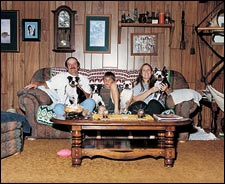

Sporting a mohawk at seven Pause, then play: from left, Dave, Roger, and Terrie Carver, with Black Jack, Longtail, Bubba, and Wilma

Pause, then play: from left, Dave, Roger, and Terrie Carver, with Black Jack, Longtail, Bubba, and Wilma The mother was allowed to keep him on two conditions: She promised not to take the methamphetamine anymore, and she promised to meet with her probation officer every couple of weeks. The arrangement seemed to work for a few months. Then, suddenly, it didn’t. The mother missed her appointments. The police came to check on the baby, and they saw that now he even looked unlucky. His sumo-wrestler thighs were lean. His eyes seemed stunned and blank. When they undid the baby’s diaper to change him, they saw that his hipbones stuck out.

So the baby went to a new family, a couple who could no longer have children of their own. The people weren’t rich, but they had a good place to live, with tall oak trees and a pond with fish and a basketball hoop and a tree house. They loved the baby. They nursed him back to health, and as soon as they could they adopted him.

Seasons passed, and the baby grew into a boy. He did turn out smaller and skinnier than other kids his age, and he also turned out to have a terrific amount of energy. He slept little. He jumped off tall furniture. At two, he could hurl a baseball with surprising accuracy, beaning unsuspecting adults between the eyes. The energy made him fun to be around, but it also got him into trouble—with teachers, with other kids, with everyone. His parents tried hard to find something that would suit the boy’s restless nature, things like music, karate, soccer, and baseball. But nothing seemed to fit. The parents felt like they were fighting against the methamphetamine. They felt trapped. They wondered if the boy would always be unlucky.

Then one winter, just after he turned five, the boy took a trip into the Sierra mountains to try something new. And just like that, all at once, everything seemed to begin.

“WATCH THIS!”

Roger Carver is in his backyard in Placerville, California, climbing a dilapidated skateboard halfpipe with a basketball under his arm. The ramp is ten feet tall, and its plywood skin has peeled away to reveal the dinosaur ribs of its wooden innards. Roger wants to see if he can make a shot—not a regular basketball shot, but a “hekka-far shot.” Hekka-far is what you call a really far shot, the kind of shot fans take at the halftimes of NBA games to win a million dollars. Roger, who is 12, has short blond hair and cheeks flushed bright pink. He has spent the last four hours bouncing on a trampoline, climbing a tree, fishing for bass, spinning the basketball on his finger, practicing a new 360 grab move on his skateboard, and hopping around the yard in quick, froggy jumps. He is not tired; Roger is never tired, except at night after he takes his white pill, and sometimes not even then.

He reaches the top and stands in the sunlight. The ball looks large compared with the rest of him. Roger is a shade over four-foot-six and weighs 76 pounds, though he’s pretty sure he’s gained a little lately and now is up to 79, seriously.

“Don’t you go and fall, Roger,” his mother, Terrie, warns in a fierce voice.

“Mo-om!” Roger says exasperatedly. “I’m not going to fall.”

His voice is the first thing you notice about Roger Carver. It’s high and lilting, a voice his parents liken to that of a cartoon chipmunk. Roger does not care for the sound of his voice, but it doesn’t stop him from using it all the time: doing impressions, sound effects, and, most of all, singing. Roger has always liked to sing. Up and down the radio dial he goes, producing clear, trilling versions of Creed, Blink-182, Santana, Pat Benatar. Heart-breaker, dream maker, love taker, don’t you mess around with me. He likes to sing while he’s snowboarding, made-up songs that flow to a fast and unfollowable rhythm—boom a bappa boombamboom bappa boom bappa bop.

No, Roger Carver will not fall, because he was born with hekka-good balance. How good? Well, you can add it up: There’s the 19 national snowboarding championships he’s won over the past six years in the sport’s five events (halfpipe, slopestyle, slalom, giant slalom, and boardercross). There’s the fact that he hasn’t been beaten in the slalom or giant slalom since he was seven. There are the four snowboarding videos and the movie with Michael Keaton (which was kind of lame but which you might have heard of anyway, called Jack Frost). There are the dozens of boxes of free clothes and equipment, and the photos in Transworld Snowboarding. But the most impressive thing about Roger’s balance is that he never seems to fall. If they gave a medal for not falling, Roger would win every time. When people try to describe it, they make comparisons: He is like a rag doll. He is like one of those weeble-wobble toys that always bounces back. They make comparisons because merely telling the story doesn’t capture the sheer impossibility of it. Like the time this year at the nationals when he caught an edge and shot 50 feet off the course, then somehow turned, nailed the gate he’d missed, and went on to win. Or the nationals slalom race when he beat all but five of the men in the 30- to 39-year-old division and everybody made a big deal out of it because he’d just turned eight.

There are tons of stories like that.

There are other stories, too, ones that don’t have anything to do with snowboarding but with the other stuff Roger does. Because Roger is always doing something. He is always skateboarding or doing tricks on his mountain bike or jumping really high on a trampoline, higher than Jason or Chad or Josh or Ethan or any of the other kids in his sixth-grade class. If you spend any time with Roger, you get the distinct impression that he could never not be doing something. Like right now, for instance, as he stands on top of the broken-down skateboard ramp and throws the basketball at the distant hoop. He watches it fall perfectly through the net and sends that high voice ringing across the yard.

“Did you see that? Did you?”

WHEN GROWN-UPS, in particular coaches and national- team organizers, talk about Roger, their voices get high and excited, sort of like his. They talk about the Olympics and sponsorships and careers. They say that snowboarding is the hottest sport in America, and that whoever turns out to be the hottest kid in the hottest sport—well, that kid is going to be very hot indeed. They talk about Shaun White, that freckly 16-year-old Californian who reportedly earned close to a million dollars last year, along with two automobiles he wasn’t old enough to drive. They talk about Roger and they use phrases like “a younger Shaun” and “cross-marketing” and “magazine kid.” They say all those things while at the same time pointing out the dozens of roadblocks that stand between any 12-year-old and greatness. Roger, they say, is one of a handful of promising snowboarders, the majority of whom, if history is any guide, are as famous at this precise moment as they will ever be.

But in the end, they believe in Roger. The scope of his accomplishments, his foundling status, his blue-collar background, the kismet of his last name—all of it tells them that this isn’t about talent or potential, it’s about destiny. These grown-ups, like all grown-ups, hold in their hearts the idea of the Wonder Boy, and they want Roger Carver to be that boy. (The deeper truth is, we want to be that boy, and this is the closest we’ll come.)

But ask Roger about the future and his eyes rake the ground. He says something like, “I want to go into the Coast Guard, you know, so I can drive boats.”

What else?

“Getting a new four-wheeler would be cool. Or winning a truck.”

What else?

He thinks. A game board of lines forms on his brow.

“I want new tires for our four-wheeler trailer. So I can haul my stuff and friends around. You know, to do things.”

That’s it?

He thinks.

“That’s it.”

Roger may be 12, but he knows that being the Wonder Boy is a complicated job. He knows this partly through his parents, self-sufficient and resolutely undreamy people whose voices do not get excited when they talk about their son’s snowboarding future. But mostly he knows it through experience. He knows how sneakily the forces of destiny operate, how they slip invisibly into your blood, how they can catch you by surprise.

“I really don’t know why I’m good at snowboarding,” he says. “It’s just luck, I guess. I mean, I just got into it, and then here I am.” He laughs, an incredulous chirp. “Roger Carver.

“I know my life is my real life,” he continues. “I know I’m not living a ghost life, but still, sometimes it feels weird. I mean, who am I? Sometimes I think about it and it’s like, how can that be? To go from that life to this.” He shakes his head. “The odds must be one in a million—no, make that a billion. One in a billion.”

IF YOU COULD GET a hekka-strong microscope and take a picture of a single molecule of methamphetamine, you would think that it looked a little bit like a tadpole. There’s a ring of six carbon atoms at the head, then a tail made of four other carbons and a nitrogen, the whole thing buzzing with energy. And that’s the way it works in the body—it buzzes through the blood up to the brain, and when it gets there the drug plays a trick. It tricks the brain into releasing dopamine, which is the stuff that makes you feel pleasure and allows you to concentrate.

If you were a baby and you had a lot of methamphetamine in your blood (and the doctors said that Roger had a lot), your brain might be different afterward. Researchers aren’t yet sure exactly how or why, but methamphetamine exposure seems to be associated with a number of conditions, including paralysis, cerebral palsy, seizures, short-term memory loss, social problems, attention disorders, and hyperactivity.

One theory is that methamphetamine reduces the brain’s ability to produce dopamine on its own. Without enough dopamine, the world seems dull. You get bored, and because you’re bored you do crazy things, like yelling or jumping up and down or not keeping your hands to yourself. “The pleasure you or I would get out of lying in bed reading a good book, they get by jumping off a bridge,” says Paul Brethen, director of the Matrix Institute, a drug-treatment-and-research organization near Los Angeles. “They need to be out on that cutting edge because it’s the only thing that makes them feel alive. Or they take pills.”

Roger takes blue pills called Adderall, which are amphetamines, and white pills called clonidine to help him sleep. He takes two blues when he wakes up, two more at noon, and one and a half whites before bed. Taking the pills makes him feel good. But so does not taking them.

“I feel more energized right away,” Roger says. “It makes me feel like…’Take the chance.’ Take the chance—like, raising my hand or yelling or something. Like I’m not choosing it, but I am, automatically. I don’t like it, either. I get in trouble for it and it’s not cool and everybody thinks I’m a bad person.”

But right now, Roger is feeling OK. It’s a perfectly blue May afternoon, and he’s in his front yard. Standing still. This is worth noting because it doesn’t happen very often. You can sense the effort behind it in the tensed way he holds his arms, in the silent brushing of his sneaker against the dirt, and mostly in his eyes, those feline, slightly hooded blue eyes, which flicker as if he has a secret he can’t wait to tell.

“Come on,” he says. “I’ll show you some things.”

If possible, Roger looks skinnier up close than he does from a distance. His shoulders seem broader, his arms more dangly, his neck more fluted. His body resembles that of a basketball player who has unexpectedly shrunk to half size, an impression reinforced by his wardrobe of loose T-shirts and shorts. The T-shirt fits well enough, but the shorts are held up with a belt, the end of which hangs below Roger’s knees like a vestigial tail. This puzzles Roger, who’s positive he’s been gaining weight.

“See?” he says, pulling up his shirt and gathering a half-inch of skin between his fingers. “I’m starting to get a belly.”

“Right,” says his friend Cody, who has come over to skateboard.

“No, really,” Roger persists. “It’s true.”

Roger lives with his parents in a modest one-story cedar- shingled house on the hilly outskirts of Placerville, population 10,000. It’s a hobbity, fifties-era house with plywood countertops and a hammock chair and four wild-eyed Boston terriers that patrol the living room. It is small, which is fine, because the Carvers spend most of their time outside, either in the garden or by the fire pit or sometimes, on hot summer nights, sleeping on the trampoline. Privacy is no problem—their six acres are bristly with trees and bordered on the north by a tall wooden fence. To Roger, the best part about home is the skate park, a vast, curvilinear moonscape of concrete. No one else Roger knows has a skate park in his yard—never mind one built by his father. His eyes dwell on the half bowl, the rails, the pyramid. He looks at it so intently that he doesn’t hear his mother approach, her sandals crunching on the pale gravel.

“Did you take your pills today?” Terrie wants to know.

“Yes!”

“Did you pick up your fishing rod?” his father, Dave, calls from the workshop. “I thought I saw it out there on the grass.”

“I did!”

TERRIE, WHO IS 42, has long hair and slate-blue eyes, and works summers in the office of a photography studio. Dave, 47, is tall and mellow, with an angular face and big, watery eyes. He’s co-owner of a concrete company in town. Standing shoulder to shoulder, they vaguely resemble the couple in American Gothic, emanating the same brand of capable, pitchforked watchfulness. They watch Roger all the time, making sure he has all his gear, making sure he’s watching his money, making sure he isn’t doing anything too dangerous. They’ve built a framework of rules around him, a clear set of dos and don’ts that reside in their eyes as surely as if they were chalked on the skate-park concrete. Be polite—always thank your coach at the end of the day. Wear your helmet when you’re boarding, even if nobody else does. Don’t talk back. Don’t brag. Don’t lose the gear your sponsors send—if you do, pay for the replacement. And of course, don’t forget to take your pills.

“If he misses one, you know,” Terrie says. “He’ll walk in that door moving twice the normal speed, talking back, and he’ll be doing that laugh.”

“If I hear the laugh, oh my God, it’s all over,” says Trevor Brown, his alpine coach at the Heavenly Ski and Snowboard Foundation. “Instead of going 100 miles an hour, he’s going 300. Then it’s Tasmanian devil time.”

“The laugh,” Dave says, nodding. “You could do anything to him and he’ll just keep laughing at you—I mean, it’s like Jekyll and Hyde. Without the pills, he’s a different kid.”

“I tried homeopathy, herbs, everything,” Terrie adds. “But when we tried the pills, they worked, and so he takes them. We literally couldn’t live without them.”

Terrie and Dave talk like this in front of Roger. They don’t do this to be cruel or show-offy; it’s just family policy. Within the Carver house, the most important rule is to Put Everything Out There. So they do, even when those things are embarrassing. Like Roger’s problems in school (“Math is a huge struggle,” Terrie says. “He has trouble following patterns”). Or his outbursts in class, or the recent fine-tunings of his medication. All are discussed in clear, impersonal voices, as if they were chatting about the weather. Listening to Terrie and Dave talk to Roger is to hear one message repeated over and over: “Yes, your brain is different.” And you hear its implied corollary: “Get used to it.”

“They’re always reminding me of stuff,” Roger says in the living room. “I think they’re good parents—not too overprotective, not too underprotective.”

“They’re pretty cool,” Cody agrees, flopping on the couch and closing his eyes. Roger looks at his friend sympathetically. Roger is one of those kids who has lots of friends instead of one best friend—partly, it seems, because he tires them out quickly. He watches Cody for a second, then turns away.

“So,” he says, “want to see my room?”

IT’S A COZY, cavelike space, a cluttered mix of dark and light. A sheep skull gazes from the paneled wall. A toy monkey grips a trapeze. Glinting armies of rocks are deployed on two large shelves. The sun catches a bright square of yarn that Roger crocheted when he was younger. (“I was into that for a while,” he explains.) The only clue to Roger’s sporting life is the snowboards stacked like cordwood at the foot of his bed. If you ask why he keeps them here and not in the shed or the garage, he will shrug his thin shoulders.

“I dunno,” he says. “Maybe I just like having them close.”

Roger begins to unstack the snowboards, laying them gently on the bed, where they tilt and slide as if they might suddenly do a trick on their own. When he’s finished, there’s a bright pile of 22 boards, from the new jet-black K2 Zeppelin (K2 has been Roger’s board sponsor since he was seven) to a dinged-up purple board barely half its size. He unearths the Barney-colored plank, holding its edges with his fingertips.

“This is really, really old,” he says. “See?”

If you ask him how he got started snowboarding, Roger will tell a story. He was five. Dave and Terrie’s biological son, Dustin, was 15. Roger liked Dustin a lot, and Dustin liked snowboarding a lot. So …

“I was on the hill,” he says, “and this instructor was trying to tell me something about keeping my arms straight and I just took off and went schkeewww, schkeewww, schkeeewww. Then my mom saw me and was kinda surprised.”

What happened next?

“For the first year I followed Dustin and his friends around, and they were really nice to me and let me come and everything. Then a whole bunch of stuff happened.”

What kind of stuff?

He hesitates. His knuckles work a quick rhythm on the purple paint.

“You know,” he says. “A lot.”

Officially, Roger’s career began with his fifth-place-overall finish in the United States of America Snowboard Association’s seven-and-under division in 1997. Then came three straight years in which Roger won the alpine/freestyle combined titles and began to receive some benefits of his newfound stature: sponsorships, invitations to K2’s summer house in Mount Hood, getting sent by RipCurl to the Whistler Camp of Champions, the nonspeaking role as a flame-haired snowboarder in the Keaton movie. (“It was fun, sort of, but mostly boring,” Roger remembers.) Then the last two years, in which Roger won the overall alpine and finished third in combined. Meanwhile, the sport exploded. Participation in the USASA nationals went from 600 to 1,200; corporate sponsorship went through the roof; and along came the inevitable rise of formalized coaching programs built to churn out camera-ready superstars.

From their sleepy Placerville outpost, Roger’s parents regard the frenzy with stolid bemusement, not noting the economic changes so much as the cultural ones, namely the appearance of what they call “soccer parents”—that well-dressed, energetic breed who badger coaches, suck up to sponsors, and get, as Dave puts it, “a little overinvolved.” Roger has snowboarded with several Tahoe-area teams over the past few years, most recently at Heavenly. These teams are made up of kids from Roger’s age on up whose parents pay around $1,500 for them to snowboard every weekday from December to March and to race in USASA events on weekends. Other top kids attend elite sports-oriented academies like Vermont’s Stratton Mountain School ($26,000 a year in tuition). But the egalitarian South Tahoe scene suits the Carvers, who homeschool Roger during the season and enroll him in the local public school the rest of the year. For nationals, which in past years have taken place in Telluride, Colorado, and Waterville Valley, New Hampshire, they plan a family vacation. Dave and Terrie hear about other snowboarders getting private coaches and it makes them smile, not just because of the expense.

“Truth is,” Dave says, “I don’t think one person could keep track of him.”

“He’s a maniac on the hill. He never gets tired and he never wants to quit,” says Kyle Frankland, who coached Roger for two years on the Donner Summit Snowboard Team. “He won’t eat, he won’t drink, he’ll just keep making turns.”

ROGER’S TURNS, like all true athleticism, look ludicrously simple. When he’s on his board he is relaxed, his hands loose, the fingertips slightly curled. As the turn initiates, his knees bend slightly and he seems to hang over the snow, a marionette suspended by invisible wires of speed and centripetal force. Watching him, you’re struck less by his speed than by the stillness that lies at the center of each turn. Riding a rail, the coaches call it, because that’s exactly what it is—locating an invisible curve of steel beneath the snow and following where it leads.

“It’s not something you can teach; it’s something he was born with,” says Trevor Brown. “When he turns he doesn’t let it break loose, he doesn’t skid or scrub, he just…he just”—Brown searches unsuccessfully for a less corny word—”carves.”

Roger has come up with a theory of why he is so good at snowboarding. He thinks there might be a part of him that’s like a robot, that behaves as if it were programmed, generating tricks and turns as his other self pushes the buttons.

“Something in my mind tells me to do these things,” he says. “It’s not me, it’s my body, seriously. My body just does it. It’s weird—it, like, commands me, almost.

“It’s hard to explain,” he continues. “Maybe what my birth mom did, you know, making me drug-exposed, maybe it makes me better and maybe it doesn’t. I mean, maybe what she did deformed me in a way—or maybe it deformed me in a good way. I’ll never know—and I never want to know.”

Roger says that a few times—that he never wants to know about his past. But even so, he often ends up talking about it, about his birth mother. It becomes clear that his mind is circling this subject as it circles everything.

“Sometimes I try to imagine what she looks like,” he says. “Mom says she looks like her, but taller. I dunno. I have three other brothers and sisters. They’re older, and I guess I look like them.”

He fusses with his belt, jamming the tail into his pocket, pulling it out.

“I sometimes talk to my sister, on the phone. She wants to snowboard, too—they live a couple towns over, I think. With my grandma.

“I talked to her a few times. Not in real life, but on the phone. She’s, like, really nice. She’s interested in talking to me, which is really good.”

He shakes his head.

“It’s weird,” he says. “It’s all really weird.”

Roger knows about methamphetamine. He knows it’s a problem around Placerville and other places—he’s heard about the labs in the woods, about people being afraid to camp down by the Cosumnes River, and he’s seen the skinny, intense people walking around town. Knowing helps, but it creates tangly questions: Why did my mom do drugs when she was pregnant? What did it feel like? Why couldn’t she quit? Didn’t she love me?

“We tell him that drugs mess people up,” Terrie says. “They might not be bad people, but when they do those kinds of things you don’t want to be around them.”

“He always says, ‘Tell me the truth,'” says Dave. “He doesn’t want any B.S.”

“The truth is, these pills are part of his life forever,” Terrie says. “What his mother did changed him, period, and he has to know that. He has to know the story behind everything. So we tell him.”

When Roger asks why Terrie couldn’t have any more kids after Dustin, he hears the story about the ovarian cyst and the emergency hysterectomy. When Roger asks about his birth father, he hears the story about the drug smuggler who went to prison. When Roger asks about Terrie’s childhood, he hears about a teenager who found out that the man she’d been calling Dad for 16 years wasn’t her actual father, and he hears his mother’s fierce voice say, “You’re not going to have any surprises like that.”

So Roger listens to the stories and his mind keeps churning, pushing for more, and eventually Terrie and Dave are left with the last story, the only story that means anything. They tell him about the baby in the hospital, the unlucky boy whose hipbones stuck out. They tell him about the little kid who could hit people between the eyes with a baseball, whose mother took him to a mountain one day and then turned to see him flying down it. They tell him the story and Roger listens and tries to feel his way along.

THERE’S A GAME Roger likes to play in the car called Name That Song. You hit the seek button and see who can name the artist first. If you do, you get a point.

“It’s a good game,” he says. “You’ll like it.”

Driving with Roger is fun and a little tiring. It’s fun because he’s always looking out the window and noticing things you might not. It’s tiring because, at the same time, he’s fiddling with the air vents and the fan, turning on the hazard lights, leaning over to check the speedometer.

“Britney,” he says, and hits the button.

“Train.” Click.

“Destiny’s Child.”

To this soundtrack, you move along the roads, tracing in and out of canyons, up and down steep hills under a dome of California sky. You drive through tunnels of trees, past sprawling vineyards and rusting mansions of corrugated metal. You see streets: Glory, Magic, Paydirt, Serendipity. You see people: An elderly jogger. A couple pushing a double stroller. A man walking a black dog.

“I want to get off my pills someday,” Roger says. “I think if I stay around regular people a lot, maybe that will help me. I met a guy one time who used to take pills, and now he doesn’t. He controls it with his mind—you know, just by thinking about it real hard. I guess that’s what I want to do in the future. But it’s really hard to know what’s going to happen. You know, who knows, really?”

When you ask them about the future, Roger’s parents express a similar feeling.

“We’ll probably do snowboarding again next year,” Terrie says. “Then, nationals are in Maine, at Sunday River. That would make a fun trip.”

What about further down the line?

“Too soon to say,” Dave says. “Way too soon.”

“We don’t think about it,” Terrie says firmly. “I’m not saying Roger couldn’t go pro or do the Olympics. I’m just saying that if he doesn’t, or if he decides to quit tomorrow, it will be fine with me.”

“He could, too.” Dave says. “He could walk in the door and announce that he’s done. He did it with soccer and trick-or-treating. Just came home one day and said, ÔI’m not doing that anymore.’ And he didn’t.”

Roger clicks to a Tom Petty song. It’s a good one, so he takes his finger off the button and lets the song play out. His hands tap the dashboard and his body rocks back and forth in the seat, and when the chorus comes he can’t hold it in anymore. He sucks in a deep breath and just belts it out in that chipmunky voice—Yeah, I’m free, I’m free fallin’!

When it’s over, he’s quiet for a while. Then Roger notices something.

“There,” he says, tapping on the glass. “There’s a mountain over there with a cool story.”

Let’s hear it.

“It’s an Indian place and it’s really old. The story is that if an Indian brave was sad because something bad happened—like they couldn’t get married or if their wife died or something—they would climb up to the top by themselves and just jump off, and on the way down they would magically change into some animal before they hit the ground—you know, a hawk or a bear or something that was their true spirit.”

Roger thinks about this. He futzes with the air vent some more, looks at the green world speeding past, punches the seek button.

“That’s a good story,” he says.