A funny thing started happening around here a few years ago: kids. Colleagues, contributors, athletes they all started having them. And everybody seemed to be struggling with the same question: How do I raise an active kid while still doing all the stuff I love? So we started asking around. Among other surprising truths, here's what we learned: Hauling two babies on a Third World sojourn isn't (necessarily) insane. There's plenty of adventure to be had in the suburbs. Being forced to run as a child isn't such a terrible thing. Basically, that we should live like we always have just with more gear.

Rock Hounds

Explore your own backyard.

We never went to Disneyland. We never left the state, Oregon, except once to visit Yosemite another time, Yellowstone. Our vacations were more expeditions. Weekends, summers, we would fill the back of our Ramcharger with picks, shovels, trowels, paintbrushes, fly rods and tackle boxes, a canvas tent, and balled-up, twined-up sleeping bags that looked like pupae. The cooler we set in the cab to pull cold Cokes and summer sausage from as we drove into eastern Oregon to rock-hound and fossil-hunt. On the console rested Forest Service maps, roadside geology books, and my father's .357. One time I asked him why he kept it there and he said, “Because you never know.” We drove to the Ochocos, to Christmas Valley, to the Malheur refuge. We hiked canyons where we spotted western rattlers twisting along dry riverbeds, a cow carcass ravaged by coyotes, and basalt walls splashed with pictographs, etched with petroglyphs. We drove over cattle guards and along dirt and cinder roads and parked in the shade of gnarled juniper trees that seemed to twist upward in despair.

The air was hot and dry and smelled of sage. Our lips cracked and bled. We uprooted petrified logs, hunks of obsidian, quartz, agate, opal, jasper, nests of thundereggs and mudballs. We chipped away at the fossil beds outside of John Day and stacked in our truck squares of volcanic ash with bones and leaves imprinted on them. With these we decorated our house, jeweling every windowsill and bookshelf, every dresser and hutch. Once, we unearthed a deer skull encased in pink crystals and later set it in the center of our dining-room table like a sugared ham.

I used to complain. When my friends went to Florida and California and Mexico, and when I unrolled my sleeping bag in the sand and lay my scabbed, muddied body down on it, I wondered aloud why we couldn't be more normal, why we couldn't climb on airplanes and fly to faraway places and return with T-shirts advertising the name of some themed restaurant. My father would respond only by looking at me with hooded eyes.

I have still never been to Disneyland.

—Benjamin Percy

Shut Up and Eat Your Jellyfish Tentacles

Feed their fearlessness.

We were at a fancy ryokan resort in the mountains near Nagano, Japan, when the waiter arrived with the restaurant's signature dish. He flashed a slightly awkward smile as he set the big platter down before my wife and me and our three young boys.

“Basashi,” he said, with a grand gesture.

“Basashi!” we all repeated with gusto. It sounded delectable! So we gamely tucked in. It appeared to be some sort of meat. It tasted good, but it glistened in the light, and its consistency was slightly strange. For a split second I thought of the movie Soylent Green.

“Basashi, you rike?” the waiter asked.

“Hai,” I said, “but what is it?”

“Horsu,” he said. “It is raw horsu meatu.”

Slathered with enough wasabi, the cold, bloody horse mush went down just fine. Butit was only the first course in a meal that included jellyfish tentacles, still-squirming river fish, squid, pregnant snail, and fried locust. (Mmmm, crunchy!) And our boys ages 2, 4, and 7 at the time ate all of it. Ranging over the planet, we've been able to dangle before their minds the concept that taste is relative, that what we think is “normal” isn't. Star fruit in Costa Rica, poi cakes and a whole hog baked in the ground on Maui, escargots and beef tartare burgers in Paris these and other uncommon ingestions made big splashes on their imaginations. But it's not just the weird and striking discoveries; it's the grace notes. At the butcher shops in County Clare, Ireland, the farmer's name, address, and phone number was right there on the tray. That raising and butchering animals could be proud and personal professions, not some anonymous faraway industry, was paradigm-shifting for my boys.

A few months after the basashi, we were in a restaurant on Sado Island, off the mainisland of Japan. The waiter lit Bunsen burners beneath five moist abalones on the half shell. Soon there was a crackling sound, and I realized the large mollusks were not only fresh but alive: They jerked spasmodically at being cooked in their shells. After a few minutes of torture, my abalone rose up in one final death shudder and then fell, flaccid and ready to eat. The boys found this spectacle mildly distressing, but they got over it. The stuff was delicious.

—Hampton Sides

Lost in the Woods

The 'burbs ain’t so bad.

Indians on the one side, pioneers on the other. My dad's stories of our Native American and European ancestors worked an easy sorcery on my Huck Finn brain when I was a kid. The narrative backdrop was always the wilderness of the virgin South, which I had a stunt-double parcel of right around the corner and down the hill, a modest green paradise overhung with bluffs,engraved with streams and creeks, pocked by pools and ponds, and everywhere harboring fortresslike stands of ancient elms, oaks, and hickories all a-wiggle with grapevines. But we didn't live deep in the sticks or anything; this was just the suburban flank of Memphis, Tennessee, surely the chlorophyll capital of the USA.

So into the woods I went dreaming, whenever I could, on bike or on foot, all year long and in any weather, with friends or alone but always armed with the tools of target= practice, bushwhacking, and whittling. Primitive mechanical engineers, we fashioned tackle and maneuvered stout windfallen timber to bridge any water we couldn't make like Tarzan across. In summer, a lone great blue heron and hosts of catfish, crawdads, and dragonflies kept us company as we swam the pools and fished miles of meander with homemade “baitcasters,” lost to the world of couches and cartoons.

It may have been a long-distance hike to the market or school or library from my house, but it was just a hop, skip, and a jump into another realm.

—Jeremy Spencer

Pack Mentality

The tribe knows best.

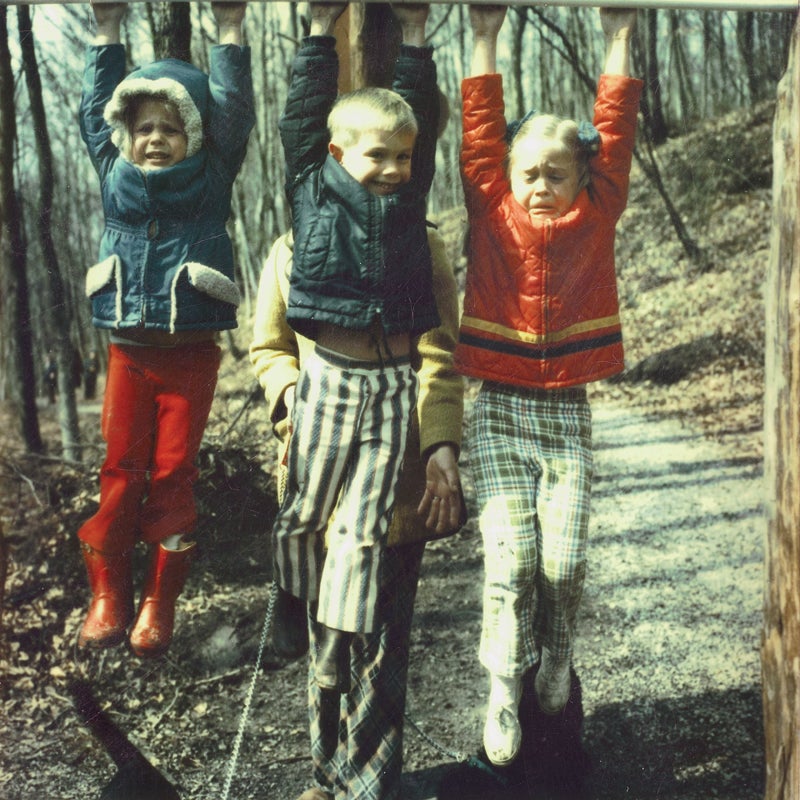

My wife, Kir, and I have a tribe of kids: Chapin, 12, Lacey, 10, Natalie, 8, and Teagan, 2. We're obviously part of the problem. I think it was inevitable Kir's the oldest of four, I'm the fourth of five but mostly I know that our happy towheaded family is the result of a series of spontaneous, perhaps even ill-advised decisions. (I'm still not sure how Teagan was conceived on a backcountry hut trip with 18 friends.) But we wouldn't have it any other way. We ski, hike, climb, ride, travel, and paddle together. Snotty noses, skinned knees, and tangled hair strangers run as we approach.

Here's how it works: We have no choice. At times it's managed chaos; control is frequently lost. We try to balance needs, and the kids know that sometimes their siblings come first. Kir is a master planner, and the house rule is always pre-pack the night, day, or week before to stay alive.

A successful tribe must have a hierarchy built on trust. This means giving kids freedom to teach and lead their kin, and it begins with the first kid. When he was just 12 days old, we hiked Chapin up Colorado's Mount Sopris in a sling. He weighed a scooch over five pounds, and Kir nursed him in a talus field. Later, we stopped at Thomas Lakes and skinny-dipped. I suppose that counts as his baptism. By the time Lacey and Natty came along, Chapin was a skier. He watched Auntie Tort and Uncle Fletch race in the 24 Hours of Aspen downhill and forgot how to turn. Thus the girls learned to ski, shrieking joyously as they chased Chapin. We shrieked at all of them to slow down.

Here's what I know: Our philosophy of family experience won't change. The best example of parenting we can think of is to keep living by letting our kids take the sharp end and lead routes at City of Rocks State Park, cliff-jump and play in the mud on river trips, and sleep on the trampoline and listen for the neighborhood bear. Yes, leaving the tribe in charge can be scary. Watching a video my son made of himself jumping his bike over his sisters brought mixed emotions: terror, anger, pride (when he cleared them), and, finally, laughter as the girls jumped up and danced, gap-toothed smiles and faces beaming in the sun. It's inverse parenting. The more freedom we give them, the more the tribe thrives.

—Penn Newhard

Runs in the Family

Lead by example.

Dad's dad was a West Pointer just like him, which made Dad a second-generation hardass. But when not wearing his aviator sunglasses and spit-shined combat boots, he would pull on his running shoes. He'd discovered running while getting in shape for Vietnam. There, he chugged in those combat boots around hilltop fire-support bases surrounded by Vietcong. He never stopped when he returned home, rabbiting to the front of the pack of America's new jogging craze as he pounded around the streets of the different Army bases where we were stationed.

One day Dad decreed that my two sisters and I should love running, too, never mind thatI was eight years old and as wobbly as a new foal. He made us compete in footraces. To earn our candy money, we kept a logbook of our runs on a one-mile course around the officers' housing area at West Point.

He was the horrible love child of Bill Rodgers and the Great Santini, and we had every right in our thrumming hummingbird hearts to despise running. But a strange thing happened on the umpteenth trip around the block: We got hooked. Maybe it was the early addiction to running's cocktail of serotonin and endorphins. Maybe it was the places running could take us: When Dad was transferred to Italy, we slapped down the cobbled streets of London and Paris's Fourth Arrondissement with him, saw the world at an eight-minute-mile pace. Or maybe it was my father headed out the door, day after day, rain or shine, and how he always returned with a beatific look on his sweaty face. He knew something special, and we wanted in on it.

—Christopher Solomon

India Jones

It’s a kid, not an anchor.

When my wife, Jess, and I announced we were taking our babies with us on a three-and-a-half month meander through India, the reactions ran from “You're crazy!” to “But they won't remember anything” to “Don't you know they can die over there?” Eight weeks into our trip, our kids have not died. In fact, our six-month-old son, Rohan, has learned to roll over and sit up and has said his first word (“Mama”) over here. Our 18-month-old daughter, Gwen, thinks that 2,000-year-old Jain temples were carved for her to play hide-and-seek in.It's not like we just jumped on the plane and showed up. Before we left, we made lists of health questions and interrogated our pediatrician to the point of fatigue. Our son's formula alone filled a 72-inch duffel. Two more duffels we filled with 350 diapers, 800 wipes, 70 ounces of SPF 50 sunscreen, mosquito nets, deet-free organic repellent, Bio Gaia (for diarrhea), powdered Pedialyte, medical records, emergency-travel-insurance cards, clothes, bibs, toys, binkies, blankies, and ga-ga's. (Don't ask.) While Amundsen opted for dogs and Scott for ponies, Jess and I have brought a Sit-N-Stand LX double stroller.

Our small caravan attracts more attention than any passing camel train. Indians love our children, barraging us with endless requests to kiss them, take their photographs, bless them, decorate their foreheads with tikka, pass them around the train from lap to lap. Even in cosmopolitan downtown Delhi, we were mobbed like Bollywood stars.

Though it's true that the days of Jess and me riding on top of the bus are on hold, the journey goes on inside it. Often we skip the temples for playtime in local parks. We nap in the hot afternoons and, at bath time, keep the water out of the children's mouths. Our sightseeing checklists always begin and end with hydration. At home, Jess and I had sketched out a languorous journey that took in only those sights with reliable infrastructure and emergency facilities. But the children have handled India so well, we've gone farther afield than we'd planned. We passed on the 12-hour Jeep ride from Jammu to Srinagar in favor of the30-minute flight, but while unpacking in our woodstove-warmed houseboat at last, with the surrounding Himalayas covered in snow, we understood that life with kids can include all this. “These are the golden years,” an elderly man whispered as I tucked Gwen in next to me on the overnight train to Jaipur. “Later they do not always want to be beside Daddy.” I know this trip will be hard to match; the kids will be this little only once, after all. Even now, Jess and I are thinking of the days when we'll tell them what we did how we took them to India in diapers and crossed the vast country on these rocking trains, the two of them asleep in our arms.

—Tony D'Souza

Girls Like Slingshots, Too

Make it up as you go.

The knife-throwing phase of my childhood was a bit weird, I'll admit. So were the blowguns and compound bows. That was definitely not how the other children in my class spent time with their parents. But it sure was a helluva lot of fun. For my father, James Dickey best known for his novel Deliverance the routines of suburban life tended to get a little dull in the hinterlands of South Carolina. If there was one thing he liked to do, it was to bring a healthy (sometimes notorious) dose of creative chaos to places he felt were lacking in it.

Dad grew up during the Depression and, fortunately, held on to an old-fashioned “get off your ass” sense of play. He'd take me out on the lake behind our house in his old Grumman canoe to look for snakes and box turtles, set up elaborate scavenger hunts for my birthday or Christmas gifts. It wasn't long before I knew how to throw a football, what to look for in a good knife, and how sextants were used for celestial navigation. Never did it occur to him that I wouldn't enjoy things like that because I was a girl, and so it never occurred to me, either.

Of all our hours together, though, the ones I remember best are those he spent reading to me from classic adventure novels like Mutiny on the Bounty and The Call of the Wild. Merely reading a book was never enough; he used maps and references to crawl right up into it. We spent an entire day once trying to crack the code in Edgar Allan Poe's story “The Gold Bug.” Those were the kind of tales, I think, that he hoped would inspire me to get out and explore our strange, mysterious world. As it turned out, he was right.

—Bronwen Dickey

The Black Sheep Chronicles

Never give in.

When my husband, Shawn, and I were still young, living in Alaska and wearing Carhartts and Gramicci, we talked about breeding an outdoor family. He was a raft guide. I worked as a backcountry ranger in Denali. The next year, we got married in a Colorado meadow. These days, Shawn's a cat-ski guide and I write. We live in Colorado on two wooded acres surrounded by a singletrack maze with our sons, Scout, 9, and Hatcher, 7. That's us, the perfect outdoor family except Hatcher hates being outside.

Scout's first real expression was a scream of glee on a chairlift in Montana, and he learned to breastfeed in a front pack while I hiked in Colorado's Berthoud Pass backcountry. Hatcher had the added advantage of stowing away in my parka during snowstorms, but his first word wasn't powder; it was vacuum. As a three-year-old, his coat of choice was not a Patagonia puffy; it was a smart, black velvet tuxedo jacket from the Gap. His profession of choice? Actor. His dream destination? New York City. Shawn and I dealt with our son's indiscretions by shoving his feet into ski boots and letting him wear the tuxedo jacket under the puffy.

As he's grown older, Hatcher has continued resisting our lifestyle. The new mountain bike Santa brought him sits in the mudroom, dirt free. He can spin a dozen 360s off the couch but can't seem to muster the strength to hike the half-mile to the mailbox. And what Hatcher lacks in VO2 max, he makes up for in manipulation: Every weekend, we hit the nordic track at Eldora Mountain, but not ten minutes in he'll fall to the ground, complaining of piranhas eating his leg muscles.

In the summer, when we go hiking in the nearby Indian Peaks, Hatcher insists on bringing along three stuffed animals. I think it's because he knows they'll leave no room in his pack for layers, a sleeping bag, or even water. Shawn deals with him by barking like a drill sergeant and rewarding his efforts with a constant stream of ZBars.

I take a different approach. I think of the sitcom Family Ties and ask myself if the Keatons ever asked young Alex to abandon his dreams of becoming a Republican. Knowing the answer, I take my son's pack and load it on top of mine. If he keeps complaining about piranhas, I pick him up and carry him. I can handle piranhas.

—Tracy Ross

Action Father Figure

Never give in.

It's hard to beat correspondent Mark Anders in the Fun Dad department. Living on the coast of North Carolina, he religiously surfs and takes his sons Luke, 7, and Nicholas, 4 on his 16-foot skiff to fish, hunt crabs, and play pirates on nearby islands. Here he attempts, with wife Ilene's help, to find out what their adventures with Dad have taught them.

Dad: Nicholas, what's the most fun thing you can do outside?

Nicholas: Ummm, run.

Luke: Run is a good idea.

D: Luke, what's your favorite piece of gear?

L: Dog. They're fluffy and they can keep you warm if you're in a tent, and they're just like blankets.

D: Good job, Luke. [Nicholas runs away.] Hey, Nicholas, come here. What's your favorite piece of gear?

N: You.

D: Why am I gear?

N: Because I get to play with you.

D: Hey, Luke, can you come over here and help me? [Both boys run away.] Listen, guys, this thing is for a magazine, and

Mom: Mark, you need to try again later. This is so not the time. They're tired and grumpy, and you're way too formal.

[Five hours later, over a dinner of macaroni and cheese…] D: Guys, if you could do any sport in the world, what would it be?

N: Skateboarding.

L: Surfing.

D: Why?

L: Because you can be awesome.

D: What should moms and dads do to get their kids to go outside?

N: Push them out! Roll them out with a truck!

L: Slap them in their tenders!

M: [Under her breath] I hope no one ever reads this…OK, what would be a fun way to get you out?

L: Get the dog to go out.

D: What's the best thing I can do to get you guys outside?

L: Well, it's a hard question. I love you and I go anywhere that you go.

D: Oh, that's a good answer.

M: That is the answer.

First Encounters

Grizzly Adams Family

“There's a bear!” This simple exclamation triggered the angriest parental outbust of my youth. At least, that's how I remember it. I was seven years old, sitting in the backseat of our family station wagon, driving through Yellowstone for the first time. We'd set out from Boston weeks before, and for several days my parents had lured us through the hot and featureless Midwest with the promise of grizzly bears. But the Yellowstone of my parents' imagination the one from the fifties, when visitors watched grizzlies from bleachers at the dump no longer existed. Bears were wild again by 1980. For my father, this must have been a tense realization; he'd overhyped the bears. So we set out on a silent drive through the park, our collective eyes peeled, and my attempt at tension relief did not go over well. There was no bear, and we never saw one. But does it matter? I've been back three times.

—Christopher Keyes

Snake!

The first naked man I ever saw was standing in Tennessee's Elk River, drinking Bud from a can resting on his gut. Imagine a dozen young girls, on an overnight canoe trip from Camp Riva-Lake, strung out along a mile of green water. We were 11 and 12 and canoed like silent Indians: We had wicked J-strokes and could empty a swamped boat over our heads treading water just like our mothers and aunts could when they were girls at camp. In this very river, in fact, my mother had flicked a water moccasin from her canoe with her paddle. I'd been spooked by a different kind of snake, but I giggled and kept on paddling. Today, kids are watched so closely, there's no room for snakes or girls alone in boats. But back then, we had sunburns and BLTs and a whole day and night of freedom ahead of us.

—Elizabeth Hightower Allen

Time Traveler

Now and then I find myself driving across the Mississippi River. It's happened four times, but the drive that propelled me on all subsequent journeys? I don't remember it very well. I was six, my sister three. My father, a dancer, booked a western tour. My mother, an actress, unbooked her summer schedule. They loaded a van and drove west from Nyack, New York. I remember a great chasm in the earth in Arizona, the red emptiness of Utah. I remember watching the world move through the sepia filter of the van's dirt-crusted windows for what felt like a year. I remember, believe it or not, the Alamo. I recently called my dad to pit my memory against the facts. “How long was that trip?” I asked. “Six, seven months?” He said, “Six weeks.” That's all it takes. Six weeks.

—Abe Streep

Leave Big Trace

When I was ten, Dad decided we should go backpacking. My brother and I didn't know what that meant, and neither did Dad. For a two-night outing in the Sierras, we brought a set of kitchen pots and pans, a ten-pound car-camping tent, enormous sleeping bags, leaky air mattresses, books, cameras, journals, a quart of bug juice (for the bugless time of year), two cheap spincasting rods, a briefcase-size tackle box (saltwater lures, jars of bait), and one giant inflatable raft with oars. It was a longer hike than we'd thought. We dragged our overstuffed, external-frame packs to an 11,000-foot lake, puked through the night from the altitude, and stumbled down miserably at sunrise. But for a sheltered kid, that first, short glimpse of true alpine scenery ice-carved cirques and marshy lakes, distant and enticing peaks set the hook for good.

—Justin Nyberg

The Love Boat

Because my parents would've had to eat the cost of the pre-paid trip, they let me go on a monthlong sail-and-scuba voyage along the Caribbean's Leeward Islands despite a recent diagnosis of mononucleosis and a leprous-looking rash caused by a misappropriation of antibiotics. (Thanks, Dr. Dad!) I boarded the 50-foot catamaran, Magic, with the caveat thatI wouldn't hit the water too hard and bust my inflamed spleen. True to myth, salt water soon cured all, and Evan, one of us nine 15-year-olds on board, offered to share his sleeping bag after mine came untethered from the trampoline and blew into the sea. We “fell in love” the way only teenagers in a tropical paradise could: navigating coral walls on night dives, picking bones out of fresh-caught fish, and brushing our teeth under a starry ceiling, all suntanned and salt-crusted.

—Jennifer L. Schwartz

Camps That Kick Ass

My parents were reasonably earthy, but I'm convinced my passion for the outdoors came from Manito-wish, a Wisconsin summer camp that, like any real camp, includes a true wilderness trip. If you're at all concerned that your child is becoming a thin-skinned lily-dipper, consider booting your beloved into the wild with a trustworthy guide, of course. Here are our five favorite spots.

Camp Manito-wish YMCA, Boulder Junction, Wisconsin

Every kid starts out canoeing. But as you get older, the options become longer up to 50 days and the destinations more exotic, including places like Nunavut (canoeing), Ontario (sea kayaking), and Alaska (backpacking). Ages 10 19; one-, two-, and four-week sessions;

KieveWavus, Nobleboro, Maine

The structure is very similar to Manito-wish's (above). Daily programs include the usual fun stuff tennis, sailing, riflery, etc. but every camper must also go on canoeing, sea-kayaking, or backpacking trips of increasing length. Ages 8 15; ten- and 26-day sessions;

Shaffer's High Sierra Camp, Sattley, California

Kids can either choose to do a little bit of everything or sign up for “program tracks” that specialize in mountain biking, backpacking, riding horses, or rock climbing. Ages 8 17; one-to-eight-week sessions;

Camp Cheley, Estes Park, Colorado

Cheley is a big commitment it only offers four-week sessions but kids get the full Colorado experience, including raft trips down Poudre Canyon, top-roping at on-site rock faces, and, for the older kids, a shot at summiting a fourteener like Longs Peak. Ages 9 17;

Camp Mondamin, Tuxedo, North Carolina

While backpacking and canoeing trips remain a focus at this 88-year-old institution, it's expanded its repertoire over the years to include things like tubing, rock climbing, and mountain biking. Boys only; sister camp is Camp Green Cove (). Ages 6 17; five-day and three- and five-week sessions;

—Sam Moulton

Folk Wisdom

���ϳԹ��� parents weigh in.

“You hear so many people say how they used to run, ski, bike, camp, etc. before the kids came along. Why stop? Make it work. We don't watch TV. We rarely go to the movies. We get out there and do the things we love. This is what our kids know.” —Steve Yore, ���ϳԹ���'s Fittest (Real) Athlete

“Scrap the crap and fill the fruit bowl. Don't even keep junk food in your house. And take kids shopping at a natural market. Let them choose healthy foods. You'll get better buy-in, and they won't feel like it's something you're pushing on them.” —Dean Karnazes, ultramarathoner and founder of the Karno Kids foundation (motto: “No child left inside!”)

“Giving kids the freedom to choose what they want to do is the only way to go. Our oldest son, George, started on skis and then chose to snowboard on his own. Family surf and snowboard trips give us time together and are clearly the purest and best times of my life as a parent.” —Jake Burton Carpenter, founder of Burton Snowboards

“Loosen up on the reins. Let your kids explore and try sports you're not familiar with. Encourage this. Overbearing and overprotective are all over. Be supportive and happy and let them be.” —Conrad Anker, climber and alpinist, is planning a family trip to Montana's Bob Marshall Wilderness

“Get your kids up and moving by joining them and creating challenges for each other. 'Race you to the other side! Try to jump over this! I bet I can kickflip before you!' (Oh, wait, maybe that's just for me.) Bottom line: Engage them instead of just telling them—and let them discover it at their own pace.” —Tony Hawk, skateboarder, entrepreneur, and Kids for Peace's 2009 Peace Hero

“Let your kids define their own dreams! Hopefully our children will reach far beyond our vision of what's possible.” —Lynn Hill, climber, is working on a video project about the techniques, culture, history, and psychology of climbing