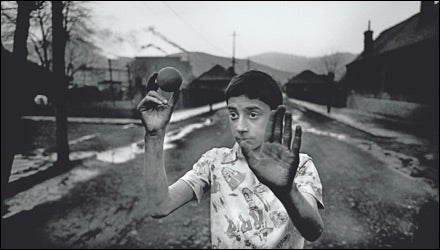

THE BOY HOLDS HIS BLACKENED PALM TOWARD THE CAMERA. Soot rings his eyes. Behind him, two plumes of factory smoke billow into the choked sky. Soon it will begin to rain.

Antonin Kratochvil

Self-Portrait by Antonin Kratochvil

Self-Portrait by Antonin KratochvilWillem Dafoe

Willem Dafoe in New York, 1990 by Antonin Kratochvil

Willem Dafoe in New York, 1990 by Antonin Kratochvil“The raindrops were black,” says Antonin Kratochvil, who took the photograph.

It’s a June morning in Manhattan, and a barefoot Kratochvil, 62, is lounging on a white couch in the Tenth Avenue loft he shares with his fourth wife, Gabriela, and two of his three sons. This is an uncommon moment of repose for a man who’s so tightly coiled and peripatetic that he’s known as “the Bouncing Czech.” Family chaos swirls all around him, the floor a minefield of dump trucks belonging to his 19-month-old son, Gavyn. Gabriela, a willowy blonde 20 years younger than her husband, is simultaneously sautéing chicken at the stove, captioning photographs at her desk, and preparing to wake their teenage son, Wayne.

��

Kratochvil, oblivious, flips through photographs he took in Eastern Europe in 1991, after the fall of Communism. He pauses over this boy with the soot-ringed eyes, who was living in the Transylvanian town of Copsa Mica, one of the most polluted places on earth. “I empathize with people who are being fucked,” he says. “When I photograph them, I am photographing myself.”

Coming from anybody else, that would sound grandiose, but Kratochvil has an innate understanding of what his subjects go through, because he’s lived it. He spent his early childhood in a Czech labor camp and grew up in Communism’s grip. After he fled Czechoslovakia, at the age of 19, he wandered Europe illegally for years, in search of refugee status, was conscripted by the French Foreign Legion, and later deserted the brutal army. He drifted to Amsterdam and then Hollywood and built a career as a photojournalist, doing what came naturally: searching out the places where conflict and suffering were rife.

The world is full of bold photographers who earn their keep by traveling to rough regions. Kratochvil towers above them all, in large part because his extraordinary background gives him a preternatural cool not to mention credibility that can’t be taught. “In what we do, the most important faculties are instinct and intuition,” says photojournalist Chris Anderson, who calls Kratochvil his mentor. “Antonin is the embodiment of instinct. His persona is that of an ogre, but he is frighteningly intelligent, the most astute observer of human behavior I know.”

During his 35-plus years in the field, Kratochvil has traveled to radioactive Chernobyl, blood-diamond mines in Sierra Leone, the Niger Delta, Pakistan in the wake of Benazir Bhutto’s assassination, Darfur, Iraq, and Afghanistan. In the past two years, he’s navigated the Zambezi River to follow malaria’s ravages and been airlifted to remote U.S. military bases in the Philippines to photograph Special Forces units.

In a few days, Kratochvil will travel to Prague to act in a film for the first time, playing the lead role appropriately, an artist in exile in a new project by Czech director Jan Hrebejk. He’s grown his sandy hair long, and a new, grizzled beard sprouts from his round face. He’s missing a chunk of his left thumb. When I ask him what happened, his blue eyes twinkle wickedly. Kratochvil’s device for deflecting serious questions is ribald humor, and he claims he lost the thumb while having sex with a virgin. “She clamped down,” he says.

His two-bedroom loft looked different 20 years ago, when Gabriela first arrived. She met Kratochvil in Czechoslovakia when she was 17 and a close friend of his oldest son, Michael. Their romance started four years later, when she was 21. When she moved to New York to be with Kratochvil, the loft was raw space really raw. There wasn’t much in it but a table piled high with negatives. Kratochvil slept in a sleeping bag. Like a gentleman, he offered Gabriela his spare.

Despite his gunslinger’s slouch toward life, Kratochvil is dead serious about his work and what drives it. His freedom is his god. “I struggled all my life for freedom. I don’t know what the fuck it is besides that it is a responsibility,” he says, meaning responsibility to those he left behind. “I owe it to them because I got out, and I have to go back.” That sounds like survivor’s guilt, but he insists it isn’t. “I have no guilt,” he says. “I’m a different beast.”

BETWEEN THE AGES of two and five, Kratochvil caught rats in a Czechoslovakian labor camp. To count his kills, he cut off their tails and showed them to his father, Jaroslav. He remembers the rodents, but he has no memory of the home where he was born. In 1949, when Kratochvil was two, men in leather coats arrived at his family’s house in Lovosice, in western Czechoslovakia, and beat up his father, an upper-class photographer and artist with social-democratic political leanings.

The apparatchik thugs declared the Kratochvils enemies of the new regime, which had been ushered in the previous year when the Soviet-backed Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seized power. Soon the government confiscated all of the Kratochvils’ possessions and shipped the family to Vinor, a labor camp outside Prague. There, Antonin’s mother, Bedricha, plowed potato fields while his father worked in a tool shop. To survive, they scavenged the dregs of the harvest.

��

Four years later, the Czech government moved the Kratochvils to a Prague tenement building that housed enemies of the state. At night, neighbors threw rocks at their windows. There was no toilet in the apartment, so to get to the bathroom, six-year-old Antonin had to walk down the hall and pass under a looming crucifix lit by a red votive candle’s flickering flame. Kratochvil counts this memory not any scene from a war zone as his most terrifying. Years later, he returned to that apartment, found the dusty cross in the attic, and took it. “I have that little bitch, that little Jesus, at home now,” he says. (He reserves the term “little bitch,” his highest praise, for only a few people, including Christ. Everyone else he calls “baby.”)

Whether it be image or object, Kratochvil handles what unsettles him by possessing it. Other things he’s hung on to: his United Nations Refugee Agency identity card and a length of barbed wire from the Czechoslovakian border, which guards snipped for him as the Iron Curtain was being torn down during the 1989 Velvet Revolution.

When Kratochvil was seven, his father gave him his first camera, a boxy Kodak Brownie, and he took to wandering the woods outside Prague with a young crew of fellow outcasts, photographing his buddies. Because of his family’s status, he had to leave school and start working for the state after ninth grade. He spent his adolescence doing construction full-time in Prague and taking pictures for fun. At 18, he got his girlfriend, Olga, pregnant and married her. She gave birth to a son, Michael. One year later, sick of hanging drywall under Communist rule, he decided to escape. He asked Olga to come with him, but she refused.

So in 1966, at 19 years old, he fled, crawling on his belly under the barbed wire that ran along the border with Austria. He took nothing with him, not even a camera. For the next four years, he moved from country to country Austria, France, and Sweden among them seeking official refugee status. He calls this period his “walkabout.” To eat, he begged, and he often ended up in jail.

In 1969, to get from Italy to France, he swam the Mediterranean for more than seven hours, from Ventimiglia to Menton. While drying his clothes on a beach in Menton, he was arrested and, weeks later, conscripted into the French Foreign Legion, the notorious army made up of foreigners and refugees. The Legion shipped him to the north-central African nation of Chad, where he fought against Libya-backed rebels for a few months. Later that year, while lugging ammunition at a Legion base in Marseille, he stole a length of rope and used it to lower himself off a high wall. He ran to a nearby rail station, hopped a commuter train, and fled toward Holland, which he’d seen only in pictures.

“I’m a professional escapist,” Kratochvil says, grinning. It isn’t so funny at night, according to Gabriela, to wake up and find him peering in your face, trying to figure out if you’re friend or foe.

In 1970, at 22, Kratochvil reached Amsterdam, walked into a police station, and was granted political asylum. Soon after, with little more than a borrowed camera and his middle-school education, he wrangled his way into the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, a prestigious art institute in Amsterdam. While there, he married his second wife, an American named Laurie Ahlman. He graduated a year early with a bachelor’s degree in photography and art history, and the Kratochvils moved to California, where Antonin hit the streets with his black-and-white portfolio.

It wasn’t long before his gritty photos won him consistent freelance work in Hollywood. After a short stint in 1973 as an assistant art director for the Los Angeles Times Magazine, he started photographing album covers for Motown groups like the Pointer Sisters and the Commodores, eventually landing gigs taking celebrity portraits for Premiere magazine. He began a rise to fame, and he loathed it.

“I hated L.A., and the place was changing me,” he says. In 1977, ���ϳԹ��� assigned Kratochvil a photo essay on Route 66. The story never ran, but he took his $5,000 check and a hash brownie a sympathetic editor offered as consolation and set out for a trip around the world that has never really ended. His father, Jaroslav, had recently died, and it was once again time for reinvention. He left Laurie behind, in his mind doing her a favor by giving her the chance to be with someone more reliable. (Laurie still uses the name Kratochvil and is a prominent photography editor. In 1978 Antonin met an American named Jill Hartley, who would become his third wife by common law. She would leave him in 1983.)

“I paid a high price for being free,” he says. “I wasn’t about to give it up for the middle-class trappings of American life.”

IT’S A WARM EVENING, and Kratochvil is waiting outside New York’s United Nations Secretariat, where a retrospective of his work from the past 20 years is about to open. A tall, well-dressed Czech woman in designer flats and a red babushka approaches him. “Are you Antonin Kratochvil?” she asks. He is. She has never seen his work before. “Will you come out to Long Island and take pictures of my house?”

“Sure!” he says. “In this economy, you never know.” He follows her through the metal detector. When she sees his photographs, her face falls. Here is a church full of people during the Rwandan genocide, which Kratochvil witnessed firsthand. Corpses were stacked hip deep, and he had to wade in among the bodies to take this picture, apologizing to the dead for the desecration. As Kratochvil ambles off to greet the ambassador from the Czech Republic, the woman collapses onto a nearby couch. “Sad,” she keeps saying. Sad.

��

Kratochvil specializes in heavy topics the show contained his photographs from the Czech Republic, Rwanda, and Iraq. But he rejects the “war photographer” label outright and hates the self-promotional concept of bearing witness that’s in vogue among some photojournalists. “Antonin detests the notion of self-aggrandizement that photographers make a living off of,” says Gary Knight, a colleague of Kratochvil’s and co-founder of VII, the New York based agency Kratochvil started in 2001 with six other photographers: Knight, Ron Haviv, the late Alexandra Boulat, Christopher Morris, James Nachtwey, and John Stanmeyer. Still, Kratochvil understands strife. He was raised in conflict, and he’s made his name and a very good living by returning to it.

Some of Kratochvil’s most controversial photographs came out of Iraq following the 2003 invasion. He was on assignment for Fortune, but he didn’t embed with the military; he entered the country by driving a rented Mitsubishi across the Kuwaiti border in the wake of an American tank, hiding in the dust. He survived by eating scraps of MREs left behind by soldiers and using tricks picked up over the years. For example: Always park ass-in, so you can get out quickly; to hide film or memory cards in a hurry, turn around and pretend you’re pissing.

The digital images Kratochvil sent back stood out immediately. He was tilting the camera at such a sharp angle that the world looked off balance. I reported from Iraq in 2003, and I remember, upon returning to the U.S., seeing a slide show of Kratochvil’s work at the International Center of Photography, in New York. In frame after frame, the charred ground loomed over oil drums, water jugs, and tank treads. Why, I wondered, given the amount of suffering, had Kratochvil taken so few pictures of people? This topsy-turvy, degraded land mirrored the apocalypse he was trying to evoke. The vertiginous angle was secondary; the ground was his primary concern. As he says, “I love the earth.”

Kratochvil’s work is so distinctive that those who know it don’t need to see the credit on his photos. Ask any of his professional admirers about his style and you’ll hear this refrain: Kratochvil is a photographer’s photographer. And, like the man himself, the work is technically much more careful and considered than it first appears. His influences range from the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch to post World War II street-photography icons like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank. Kratochvil is an art photographer who chooses crisis as his subject: a mutt.

The closest thing he has to a peer is his countryman Josef Koudelka, 71, best known for a series on gypsies he shot in Czechoslovakia in the sixties. One of Koudelka’s most famous photos, of a tear-streaked boy wearing angel wings and riding a bicycle, hangs by Kratochvil’s bathroom. “He’s still alive, baby. That little bitch is still alive,” he says of Koudelka.

The episode that has come to define whatever sets Kratochvil apart his intuition, composure, or, as he calls it, his “loose” occurred in a Croatian refugee camp in 1993. Kratochvil was visiting the camp with British photojournalist Michael Persson, then a 28-year-old hotshot working for the wire service Agence France-Presse. Persson spent the day diligently shooting a series of images he considered newsworthy: breadlines, barbed wire, refugees getting vaccinations. Kratochvil spent the day loafing around, looking at people, and occasionally lifting a battered Nikon, his arms flailing awkwardly as he shot. Looking back now, Persson laughs and says that Kratochvil looked like “a sack of shit sitting on his ass.”

At day’s end, Kratochvil asked Persson what he “got.” When Persson rattled off his list, Kratochvil said, “If that’s what you got, you didn’t get it.” It wasn’t until the two reviewed their images months later that Persson understood: Kratochvil’s pictures of lounging refugees accessed the emotional reality of the camp: boredom, drudgery, and despair, which he intuitively recognized.

Among those who work with Kratochvil, such stories are common. “Antonin swings his arm around and I can’t even tell what he’s taking pictures of,” says Haviv. “Then we go back to the hotel, and I can’t believe he got that. I was standing right next to him.” Kira Pollack, Kratochvil’s photo editor at The New York Times Magazine, says viewers don’t see one aspect of the man’s genius: his 36-photo contact sheets. Whether shooting film or digital, Kratochvil never wastes a frame.

A FEW DAYS AFTER the UN opening, I accompany Kratochvil to a Long Island medical laboratory. He’s been assigned to take a portrait of a scientist researching a cure for Alzheimer’s. As Kratochvil directs, the scientist flattens his face like a fleshy pancake against the lab’s glass door. In his white coat, the brilliant doctor looks like a crazed patient. “Beautiful,” Kratochvil says, snapping away, inches from the pane. They stop in the stairwell.

“This reminds me of Escher,” Kratochvil says, referring to the Dutch artist whose etching of an infinite stairway evokes a man trapped in his mind. We come to a hooded lab station marked HAZARDOUS.

“Can you put your head in there?” he asks.

“No, it’s hazardous,” the scientist answers.

“Are you sure?”

“No! That stuff is yuck!” the scientist snaps. Unruffled, Kratochvil hustles him on to the next shot, seating him near a window and saying that a slash of sunlight against the wall represents inspiration.

After the shoot, we return to Manhattan and drop by VII. There, in a stuffy, windowless office in the back of the slick gallery, a photo too graphic for public consumption hangs above a layout table. The image shows the corpse of a political outcast in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. A rope tail hangs around the man’s neck, his head is skinned to the skull, and his pants are pulled down. Kratochvil took the photo in 2004 on assignment for Time, but the image never ran. It appeared only once, in a show at Manhattan’s Hasted Hunt gallery, where it caused an uproar, especially among parents.

Kratochvil picks up a stack of photo books and glances at the shot. “He was probably raped and tortured before his body was dumped from the car,” he says. He is, for the moment, unmasked by what he witnessed, and his eyes flash in full-blown rage. Gone is the easy, devil-may-care mien, gone the raunch and ribaldry. He is haunted by this decisive moment. What he intended to capture possesses him.

“Since I was little in refugee camps, I’ve seen people hang themselves,” he says. “I don’t close my eyes.”