Last April, six months before the crash of Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo and the death of test pilot , I took a media tour of , the massive, costly, government-funded facility that’s situated roughly 32 miles southeast of Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. When the crash happened, Virgin Galactic was testing SpaceShipTwo in the skies over California’s Mojave Desert. But the New Mexico Spaceport is where Richard Branson is planning to base his lavish space-tourism operation, which he hopes will eventually take hundreds of paying customers on sub-orbital flights, currently priced at $250,000 a head.

What

Douglas Messier—who witnessed the crash from the desert floor—reports on the warning signs that preceded the disaster, the already rampant finger-pointing, and what it all means for the future of space tourism.Obviously, I had no inkling back then that a test-flight mishap would happen this year. But I can assure you that, even during a simple PR tour that’s designed to be fun, positive, and futuristic, a trip to the Spaceport forces you to contemplate the worst possibility: a catastrophic accident involving multiple fatalities. (Which, under existing plans, would mean up to six people perishing at once. In SpaceShipTwo, a pair of pilots will take four passengers to the edge of space after separating from a carrier aircraft called WhiteKnightTwo.) The Spaceport complex is an amazing place in a starkly beautiful setting, with stunning buildings, a 12,000-foot runway, and distant mountain ranges rising to the east and west. But when you consider the enormous challenge of what’s being planned there, and the negative outcomes that are all too plausible, it’s sobering to see it up close.

It doesn’t help that your drive to the site starts with a spin through classic Cormac McCarthy country—a forbidding desert basin called the Jornada del Muerto, which roughly means “route of the dead man.” The Spaceport was built in the middle of nowhere, in part for a grimly practical reason: if a spacecraft full of passengers explodes in the air, the debris and bodies won’t come hurtling back to earth over a populated area. Nobody wants to see that happen, of course, whoever is on board, but Virgin Galactic is going to be under an especially intense media glare if it ever starts flying passengers. Among those who have signed up for a ride are Justin Bieber, Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, and Stephen Hawking.

The tour began after the members of our little group, in various vehicles, rolled through a temporary checkpoint, parked, and went inside the smaller of the two most notable buildings at the site: the , a pod-shaped structure that houses the (NMSA), the state agency that administers the site. After admiring the Spaceport’s Oshkosh Airport Fire Truck, we gathered inside the first-floor media center—a lonely spot, since nothing much is happening at the Spaceport yet, so there’s nothing to write about or broadcast—and listened to an introductory talk by Christine Anderson, a retired civilian employee of the Air Force who serves as the NMSA’s executive director.

As Anderson explained, the Spaceport currently has two “tenants”: and (Elon Musk’s company, which has set up a limited operation there to test a reusable rocket). Occasional, smaller-scale rocketeering is already happening at the Spaceport’s launch site four-and-a-half miles to the southwest—including blastoffs by , a company that sends cremated remains into space—but Virgin Galactic is the big enchilada. Until they start doing business, the Spaceport is like an expensive new international airport that’s only being used by guys flying Cessnas in and out. This state of relative idleness is nerve-wracking for those of us who live in New Mexico, since the Spaceport, which cost a whopping quarter of a billion dollars to build, was paid for primarily by state and local tax money.

After laying out the basics, Anderson took us upstairs to show us NMSA’s mission control room, which was a surprising sight, because it’s so simple and austere. Inside a compact space that overlooks the runway, there’s not much to see other than a white-topped oblong desk, two rolling chairs, a few monitors, red curtains, and red portable sunscreens. When most of us think “mission control,” we recall images from old NASA launches—a cavernous room full of blinking consoles and white-shirted engineers and scientists. This was more like looking at the Borgsjö office suite in an IKEA showroom.

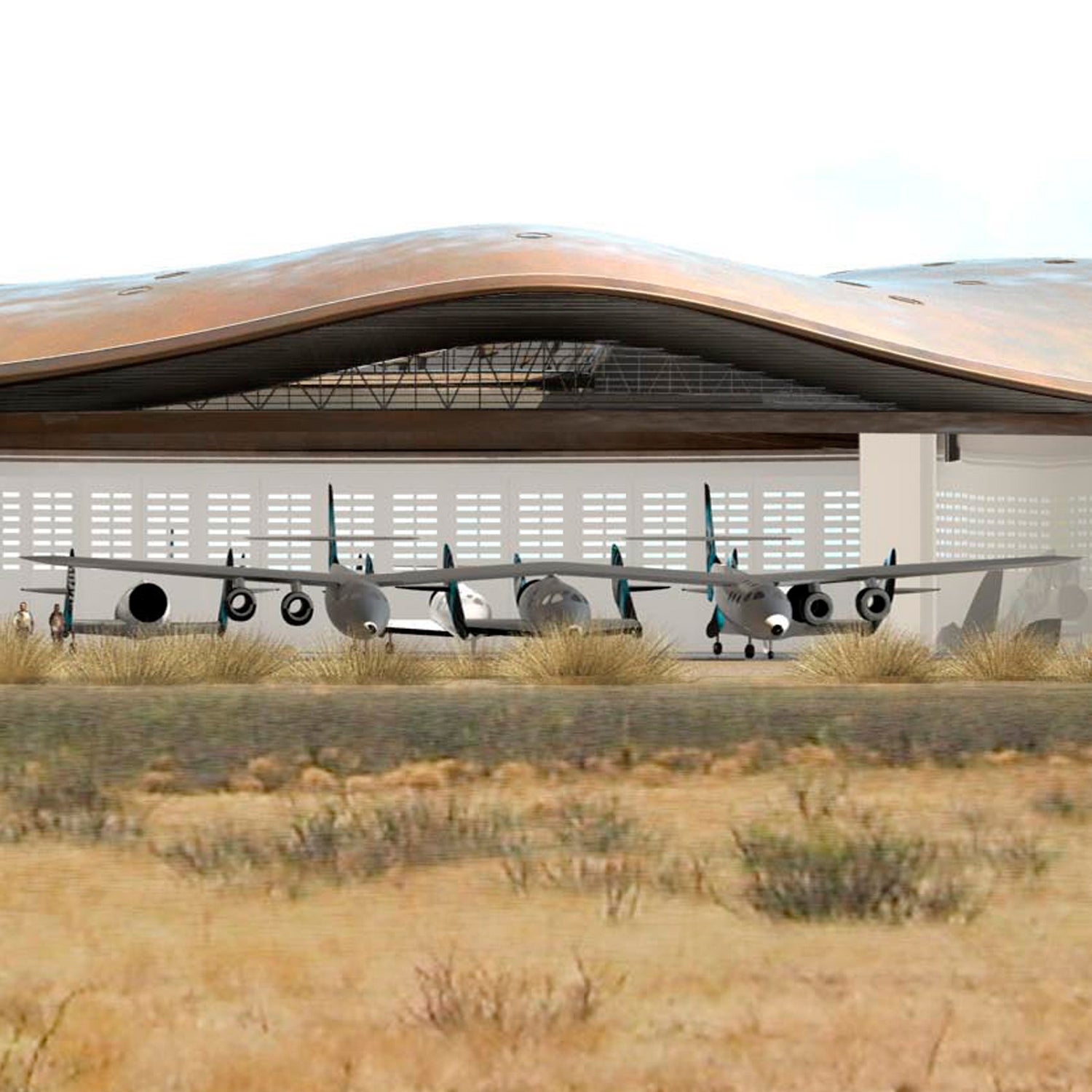

No doubt, things will be more lavish just to the south, where Virgin Galactic is based. Virgin occupies the Spaceport’s signature structure, the so-called Virgin Galactic Gateway to Space, a giant, architecturally breathtaking building that, from an aerial view, looks like a Manta ray-shaped Transformer. It cost a fortune to build and was dedicated in high style back in October of 2011. Branson was on hand for that event—champagne in hand, Virgin Galactic clients at his side—and he along with members of a dance company called Bandaloop. The governor of New Mexico, Susana Martinez, was there, too, talking about what a mighty economic engine the Spaceport is going to be.

“It’s about jobs and helping people meet new challenges and fulfill dreams,” she said. Branson called the Spaceport “a 21st century building for a 21st century business.”

Maybe, but for several years now, the takeoff date for that first, historic Virgin Galactic flight—with passengers aboard—has been pushed back again and again, and the disaster on October 31 will only delay things more. During my tour, Anderson was asked about the timetable, an inevitable question that she probably doesn’t love having to field. “It’s hard to throw a dart at a calendar and say ‘that’s it,’” she said, although she did maintain that “we’re in the ramp-up period now.”

Prior to the SpaceShipTwo crash, Branson was saying that the first flight would happen in February 2015, but that date seems impossible in light of what just happened. Nobody knows how long the accident will delay progress, but chances are good that it will be quite some time before the Spaceport starts seeing flights. (My hunch is that the delay will be measured in years, not months.) And as a story in The Economist , the mishap could give the federal government an opening to establish a greater regulatory role in what Virgin Galactic does, under the terms of the 2004 .

[quote]The Spaceport was built in the middle of nowhere, in part for a grimly practical reason: if a spacecraft full of passengers explodes in the air, the debris and bodies won’t come hurtling back to earth over a populated area.[/quote]

“[The act] prohibits the transportation secretary (and thereby the FAA) from regulating the design of operation of private spacecraft—unless they have resulted in serious or fatal injury to crew or passengers,” the story says. “That means the FAA could suspend Virgin Galactic’s license to fly. It could also insist on vetting private manned aircraft as thoroughly as it does commercial aircraft. While that may make suborbital travel safer, it would also add significant costs and complexity to a nascent industry that has until now operated largely as the playground of billionaires and dreamy engineers.”

At the Spaceport, our group wasn’t allowed inside the Gateway to Space. Instead, we were carpooled over for a look at the big runway and the Gateway’s east-side exterior, a dazzling facade of tall, gleaming glass panels under a copper-colored roof. As we milled about in front of it, taking “reflection selfies,” we were told not to get too close, because Virgin Galactic employees were inside, working away on futuristic interiors like the second-floor “mission control center” and a third-floor “astronaut lounge,” where citizen-spacemen will hang out before boarding a flight.

We were supposed to take this news as a positive sign—it’s all happening soon!—but I couldn’t shake a feeling of doubt that launches would take place in 2015. Standing there on a vast expanse of white concrete, I tried to visualize Justin Bieber coming out of the main hangar—presumably wearing a nifty, Bieber-scale flight suit designed for him by Virgin Galactic—and giving a thumbs-up as he headed off for his date with sub-orbital destiny. It all seemed so unreal. Would any of these grandiose things really happen soon? Would they ever happen? Should they?

More knowledgeable people than me are debating those questions right now. In the wake of the crash, fierce arguments have shaped up about whether Branson, as a self-anointed space pioneer, is a visionary or a huckster, with that “Virgin Galactic is building the world’s most expensive roller coaster, the aerospace version of Beluga caviar.”

I’m not qualified to comment about the future of commercial space tourism, but I’ve always thought Branson is both a visionary and a huckster, in the same shaggy-haired package. After all, the Spaceport only happened because two high-energy egotists with power and money—Branson and former New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson—had a mind-meld in 2005 and decided that a blank spot near the would be a perfect place to usher in the future. Not many people could turn such a far-fetched notion into reality. For better or worse, Branson managed it, pushing through a project whose history dates back to 2004.

A main catalyst for all this was the successful flights that year of Burt Rutan’s , which won the by reaching the edge of space, and returning safely, twice in a two-week period. The Virgin Group, Branson’s company, had sponsored the final X prize-winning flight, and it subsequently licensed technology developed by Mojave Aerospace Ventures, a Paul G. Allen-owned company that had worked with Rutan’s company, , to develop SpaceShipOne. Virgin Galactic grew out of this joint effort.

A few other states that are part of the commercial space race going on now—like California and Texas—are basing their operations at existing facilities that have grown more organically, driven by demand and commerce. (The very busy , for example, was originally the site of a small desert airfield that first opened in 1935.) Branson’s and Richardson’s big idea, though, was to go all-in from the start.

Steve Landeene, a former executive director of the Spaceport Authority, told New Mexico legislators in 2010 that the Spaceport was not a “build it and they will come” project, but that’s precisely what it was. Spaceport officials commissioned top designers and construction experts—, , and —to create a facility that, through its very fabulousness, would attract a host of other companies to what Branson and Richardson had envisioned.

When the was made in December of 2005, the accompanying rhetoric about opportunity, scale, and future growth was confident and blaring. Virgin Galactic said it hoped to start ferrying passengers by late 2008 or early 2009. Will Whitehorn, the company’s president back then, said Virgin Galactic would be doing two or three suborbital flights per day by 2011, sending passengers on two-and-half-hour trips that would include five minutes of tethered weightlessness.

Rick Homans, secretary of the New Mexico department of economic development under Richardson, told reporters, “We’re giving birth to a whole new industry.” Richardson’s office said that spaceport-related activity would generate up to $550 million a year in due course, and additional big promises piled up: the Spaceport would create thousands of jobs, touch off a real-estate boom in southern New Mexico, bring in hordes of new tourists who wanted to gawk at the facility, and put New Mexico at the forefront of an industry with as much potential for wealth-generation as Silicon Valley.

[quote]In the wake of the crash, fierce arguments have shaped up about whether Branson, as a self-anointed space pioneer, is a visionary or a huckster.[/quote]

Back in 2006, there was even serious talk of a Rocket Racing League operating at the Spaceport, which one New Mexico newspaper raptly described as “a fantastical new sports organization that plans to pit rocket planes flown by former F-16 pilots against one another on a virtual racecourse in the sky.”

“It’ll have the same impact that NASCAR had on Charlotte, or Indy racing had on Indianapolis,” one booster of the league said. “ … The tourism, merchandizing—hats, pins, bomber jackets, posters, you name it—all of that can be distributed here. What that equates to is hundreds of millions of dollars in sustainable business opportunities.”

None of that has happened yet. What has happened, in broad strokes, are three things. First, the Spaceport got built, and the state of New Mexico—now under the rule of Susana Martinez, a Republican who probably never would have built it in the first place—really has no choice but to keep it going and hope for the best. Second, Virgin Galactic has enjoyed considerable success in signing people up who are willing to put money down for a berth. To date, the company has collected more than $89 million in deposits from approximately 800 people who want to experience space flight.

And third, there was a multi-year legislative drama over liability issues, which could have had serious fallout for the entire enterprise. Before this dispute was finally resolved in 2013, Virgin Galactic made it clear that, if the issue wasn’t settled to its basic satisfaction, it might be forced to take its business to another state. Needless to say, that caused a lot of tension in the Land of Enchantment.

The problem was this. When Virgin Galactic and New Mexico forged their original agreement, the company angled for favorable terms on the liability front, as any outfits that sell high-risk activities—from downhill skiing lift tickets to guided whitewater trips—tend to do. In 2010, legislators passed a that offered Virgin Galactic limited protection from tort claims in case of an accident.

So, if you were to sign up for a Virgin Galactic spaceflight someday, you’ll be required to sign a standard liability waiver that says, basically, that you understand that space flight is an “inherently risky activity.” You’ll acknowledge that if you die or are injured in a flight, you or your survivors won’t have a claim if your death or injury happened as a result of the inherent risk.

This doesn’t mean Virgin Galactic got a blanket pass. The law says that you may have a claim in the event of gross negligence or “willful and wanton disregard” for safety. What that means in practice will be worked out if an accident happens—would pilot error count as gross negligence?—but the more immediate problem in New Mexico, circa 2010, was that the bill didn’t include any protection for manufacturers and suppliers, threatening to disrupt the necessary feeder chain of parts and equipment to the Spaceport.

It took a few years to work that problem out, because the kept lobbying against the bills that emerged, wanting to keep the window for potential lawsuits as wide as they could. This angered many people, especially politicians and editorial writers in southern New Mexico. In early 2012, after that year’s bills went down to defeat, a writer for the Las Cruces Sun-News who had voted against the legislation. The writer seemed to think that all personal-injury lawsuits were inherently bad.

“Perhaps each summer as she is planning the family vacation the primary factor in her decision is the tort laws in each state she is considering visiting,” he wrote of the senator. “ ‘I’m sorry kids, but the trip to Disneyland is off,’ she might explain to her disappointed brood. ‘If little Billy gets decapitated while on the log ride at Splash Mountain, we wouldn’t be able to collect a fair and just compensation for our damages.”

Fortunately, everything worked out all right in the end: the legislation was expanded in 2013 to include suppliers, so Virgin Galactic didn’t have to demonstrate its deep commitment to New Mexico by moving its operations somewhere else, leaving us with an empty $200-million Potemkin Village.

Though the future still looks pretty uncertain near the route of the dead man, at least Virgin Galactic and New Mexico are still going forward, together, with this wobbly partnership intact.