Can a Young American Entrepreneur Succeed Where Europe Has Failed?

As each week brings fresh reports of African and Middle Eastern migrants and refugees dying on the Mediterranean in overcrowded boats, a self-made Louisiana millionaire and his Italian wife have taken to the sea to save them.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

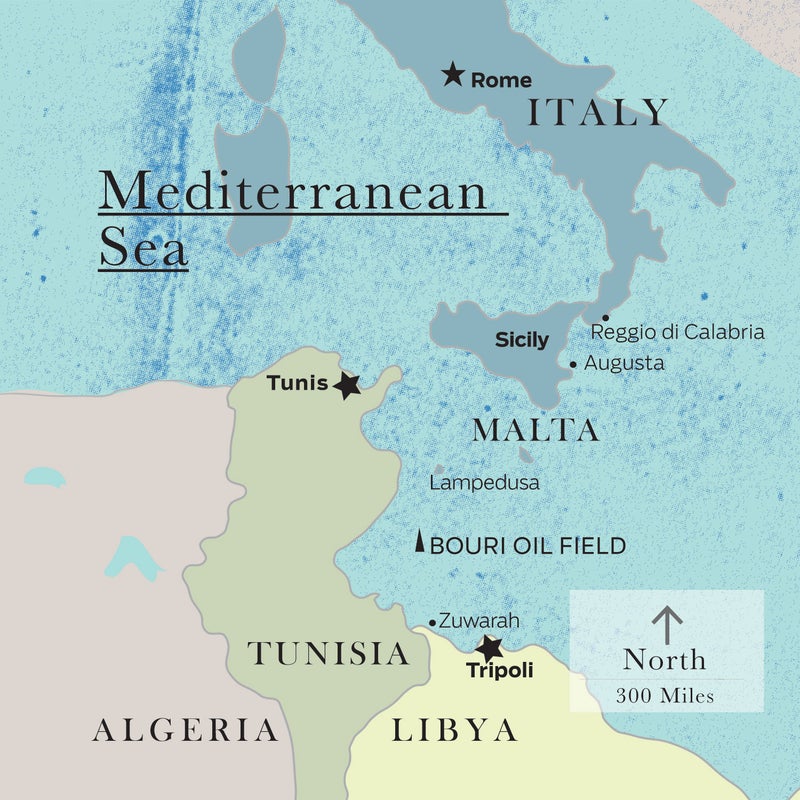

Three days after boarding the 131-foot rescue vessel MV Phoenix in Augusta, Sicily, I was standing on the shipŌĆÖs top deck on a warm June dawn, watching the rotor blades of a blue-and-orange-striped Camcopter S-100 drone shudder into motion. We were a few miles southeast of the Bouri Offshore Field, a patch of deepwater oil wells and drilling platforms jointly owned by an Italian company and the Libyan government, in the heart of the Mediterranean Sea. Lit at night by natural-gas flares and heavily trafficked by naval ships, merchant vessels, and maintenance boats, the oil field has become a beacon for refugees fleeing by sea from war and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa and Syria. Last year, 219,000 of them crossed the Mediterranean in rickety fishing boats and open dinghies, a massive flotilla organized by smugglers along the coast of lawless Libya. In their desperate attempt to reach European shores, refugees have drowned by the thousands.

The Phoenix had arrived in the vicinity of Bouri the previous night, after a 30-hour sail from the east coast of Sicily. Now we had entered a patrolling pattern. We were waiting for either a summons to action from the Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) in Rome, run by the Italian coast guard, or for visual contact with a refugee-filled boat by one of the PhoenixŌĆÖs drones. Because those vessels are often unseaworthy, and the conditions aboard are so wretched, the MRCC encourages ships equipped for rescues to intercept the migrants as soon as they exit Libyan waters and transport them to southern Italy, the closest country that will accept them. There, theyŌĆÖll remain in detention centers while their applications for political asylum are processed.┬Ā

ŌĆ£We consider a boat that is overcrowded to be in imminent danger,ŌĆØ the founder of this private rescue venture, a 34-year-old American entrepreneur named , had told me earlier. ŌĆ£When you have a boat that is equipped for ten fishermen and you have 400 people on board, including women and children, without life jackets, this boat needs to be rescued.ŌĆØ

Born and raised in Lake Charles, Louisiana, the son of an oil and gas engineer, Catrambone started a war-zone insurance company, , that provides kidnapping, terrorism, and death and injury coverage to journalists and military contractors. Based on Malta, the MediterraneanŌĆÖs only English-speaking country, it had $10 million in revenues last year. In 2013, Catrambone poured $8 million of his personal fortune into creating the (MOAS), the Malta-based NGO that deploys the Phoenix. He spent two months last year aboard the ship. During that time, the Phoenix participated in nine rescue operations and came to the aid of 3,000 migrants, carrying them to Italian ports or transferring them onto naval vessels. This spring, in its first 60 days of a six-month season, the Phoenix helped rescue 5,597 more people, and by August, the number had climbed to 8,696.┬Ā

Catrambone, however, remained on Malta this year to run his insurance business, leaving shipboard operations in the hands of his wife and partner in the venture, 39-year-old Regina Egla Catrambone, a tireless, take-charge Italian who has thrown herself into the rescue effort. On this journey in early June, there were 23 of us aboard the refitted trawler, including a Spanish captain, Gonzalo Calderon, his six-person crew, and a three-man search and rescue team made up of former members of the Armed Forces of Malta. There were also six doctors, nurses, and logisticians from Doctors Without Borders, as well as two pilots and an engineer from the Austrian defense contractor Schiebel to operate the PhoenixŌĆÖs two drones.┬Ā

The S-100ŌĆÖs blades scythed the air as it rose and hovered above the landing pad. Banking left, it hurtled at 140 miles per hour toward the Libyan coast. In a cramped control room, the two young drone pilots and the engineer clustered around a monitor, receiving high-definition images from a sensor mounted beneath the aircraftŌĆÖs nose. Around midmorning, the usual routine aboard the PhoenixŌĆöa game of Texas Hold ŌĆÖEm on the lounge conference table and chef Simon Templer, an old friend of CatramboneŌĆÖs from New Orleans, puttering around the galley preparing lunchŌĆöstopped suddenly as word spread through the ship: possible rescue. The drone had spotted a boat about 35 miles off the Libyan coast. The only question, Regina explained as the captain opened the throttle and sped south, was whether the MRCC would order an Italian naval vessel to handle the pickup or the Phoenix would be given the job.┬Ā

ŌĆ£Last time,ŌĆØ said John Hamilton, a rangy, sunburned member of the Maltese rescue team, ŌĆ£the migrants had no food or water for 12 hours.ŌĆØ Simon Bryant, an Alberta physician on a six-month Doctors Without Borders contract, turned to David Johnston, a grizzled logistician from New Zealand. ŌĆ£Time to get changed,ŌĆØ he said, and the two men disappeared below.┬Ā

This year is shaping up to be an unprecedentedly active one for ŌĆ£irregular migrantsŌĆØŌĆöa description adopted by the United Nations to avoid stigmatizing them with the term illegalŌĆöjourneying across the Mediterranean Sea. In 2009, , the EUŌĆÖs border patrol, 11,000 people made the perilous journey from the beaches of North Africa to Italy and Malta. Two years later, the Arab Spring unleashed instability throughout the region, and the number of migrants crossing from Libya or neighboring Tunisia . Since then a devastating civil war in Syria, radical Islamic terror in Nigeria and Mali, forced military conscription in Eritrea, and the beginning of a third decade of chaos in Somalia have driven those numbers ever higher. Some refugees come from as far away as Bangladesh, driven by economic misery to make marathon odysseys by land and sea before arriving in North Africa. By the end of 2015, this yearŌĆÖs numbers could exceed 250,000 people.

The deepening woes of Libya, the main launching point for migrant ships, have facilitated the exodus. Operating in the anarchic country with impunity, human traffickers charge refugees between $500 and $2,000 for a journey that typically starts in Tripoli, where the migrants are warehoused for weeks and sometimes months before being trucked to beaches west of the capital. Some of these smugglers are astute businessmen who aspire to provide a safe service for their clients. (ŌĆ£I even heard about one smuggler who allows kids under five to ride for free,ŌĆØ Catrambone told me.) But the majority are unscrupulous operators who show migrants large and safe boats in Libyan ports, then pack them instead onto derelict fishing vessels or open inflatable dinghies with no safety equipment and no crew. The migrants are given a plastic bottle of water each and maybe a single compass for the two-day journey. ThereŌĆÖs often no going back: dependent on rapid turnover and determined to prevent word from spreading about the bait and switch, the smugglers will typically force migrants to board the craft at gunpoint. The boats are piloted either by volunteers among the migrants or by a captain, hired by the smugglers, who avoids capture by leaving the boat in the middle of the journey and jumping to a smuggler mother ship. The boats are abandoned at sea and either recovered by fishermen and resold to smugglers or destroyed by EU naval forces.┬Ā

The refugees have good reason for hesitation. The crossing from Africa to Italy is now, according to the UN, ŌĆ£,ŌĆØ with a record 3,419 migrants perishing in 2014, and another 2,000 by August 2015. On an icy February night, three of four inflatable rubber boats filled with migrants capsized in frigid, storm-tossed waters off the Libyan coast. , including 29 who died of hypothermia during the rescue of 106 survivors. Two months later, a 60-foot fishing boat full of migrants capsized when it at night and the passengers all rushed to one side. A Bangladeshi survivor that smugglers had locked hundreds of people, including dozens of women and children, in the hold. Twenty-eight refugees survived.

In October 2013, Italy launched a $10-million-per-month rescue operation called Mare Nostrum, the ancient Roman name for the Mediterranean. The Italian Navy deployed an amphibious assault carrier, two frigates, and two search and rescue vessels just beyond Libyan watersŌĆöand the first year. Like MOAS, Mare Nostrum operated under the assumption that every migrant journey is a dangerous one, and its rescues targeted not only foundering vessels but also those that seemed to be in no imminent peril.

ŌĆ£ChristopherŌĆÖs philosophy is carpe diem,ŌĆØ says Regina. ŌĆ£If you have the capability, the skills, and the money, why do you need to wait? In the meantime, how many more people will die?ŌĆØ

But the program faced a backlash from conservative Italian politicians, who protested that Italy was unfairly shouldering the burden of the migration crisis. According to European Union policy, the country where a migrant first lands is obliged to handle his or her request for asylum; as a result, tens of thousands of refugees are awaiting processing in Italy. If their requests are rejectedŌĆöas happened in 21 percent of the cases in 2013ŌĆöthe migrants are dispatched to expulsion centers to await deportation. Many refugees, of course, leave Italy long before that point, making it across EuropeŌĆÖs porous borders to Germany, Sweden, and other countries, where they either work as undocumented aliens or apply for asylum there.┬Ā

Last October, Italy replaced Mare Nostrum with the far more modest . Overseen by Frontex, Triton is backed by European leaders like UK Foreign Office minister Joyce Anelay, who argued that Mare NostrumŌĆÖs ambitious sweep had that encouraged migrants to cross.┬Ā

Triton costs less than a third of what Mare Nostrum did, and it mostly patrols an area 30 miles off ItalyŌĆÖs coast. But , the number of migrants has increased sharply. After the drowning deaths of those 300 migrants last February, Nils Muiznieks, commissioner for human rights at the Council of Europe, , ŌĆ£The EU needs effective search and rescue. Triton does not meet this need.ŌĆØ

Into that multinational mess came the Catrambones. The couple first met in 2006 on a beach in ReginaŌĆÖs hometown of Reggio di Calabria, on the toe of Italy, where Chris had gone to seek out the birthplace of his great-grandfather, who immigrated to America in the late 19th century. They got married in 2010 and live in Malta with their teenage daughter, Maria Luisa.┬Ā

In July 2013, the couple were cruising the Med on a rented yacht. The trip was, in part, CatramboneŌĆÖs birthday gift to himself after a profitable year. ŌĆ£I love to take my family out and get away and enjoy life, and I convinced Regina, ŌĆśLetŌĆÖs go out and explore these waters around our home,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ he recalled.┬Ā

One day near Lampedusa, an Italian island south of Malta that has become a purgatory for tens of thousands of migrants, Regina was sunning on the top deck when she noticed a winter jacket bobbing in the water. The Catrambones asked their yacht captain, Marco Cauchi, a search and rescue commander moonlighting from the Armed Forces of Malta, about the incongruous piece of clothing. It was, he replied, almost certainly the jacket of a refugee. Cauchi told them how, during one military rescue, heŌĆÖd watched a migrant sink beneath the waves a few feet from him. ŌĆ£There were 29 people on this boat that capsized, and most could not swim,ŌĆØ he told them. ŌĆ£I saw those big eyes open, and I saw him go down so fast. I couldnŌĆÖt reach him. It stayed with me always.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£They came in two nights ago,ŌĆØ Mahmoud told me. ŌĆ£They said, ŌĆśYou will go to Italy on a very nice boat. No problems.ŌĆÖ And they told us it would take about ten hours, but I knew they were lying.ŌĆØ

Just a week before the coupleŌĆÖs cruise, Pope Francis had ŌĆ£a change of attitude toward migrants and refugeesŌĆØŌĆöa shift away from fear toward building international cooperation. Regina, a devout Catholic, had taken the popeŌĆÖs words to heart and has since enlisted the archbishop of Malta as a supporter. She has proved a vital ally as her husband developed a plan to buy a boat and ply the Mediterranean, doing the job that governments seemed reluctant to take on. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm basically the operations guy,ŌĆØ says Catrambone. ŌĆ£Regina brings in the humanitarian element.ŌĆØ┬Ā

He recruited Cauchi as well. ŌĆ£I said to Marco, ŌĆśIf I do this, will you come on board with me?ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ Catrambone told me. ŌĆ£And he said, ŌĆśYouŌĆÖre crazy, but if you do it, I will.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ┬Ā

Catrambone decided to bypass applying for grants or government aid and financed the venture out of his own pocket. ŌĆ£ChristopherŌĆÖs philosophy is carpe diem,ŌĆØ says Regina. ŌĆ£We both believed that something has to happen now, and that if you have the capability, the skills, and the money, why do you need to wait? In the meantime, how many more people will die?ŌĆØ

Just the night before we arrived, the ship steamed into Augusta, Sicily, packed with 372 refugees, the culmination of the largest rescue operation in MOASŌĆÖs short history. It began the morning of June 6, the 71st anniversary of D-Day, when the sea was calm after five days of dangerously high swells. Sure enough, as Ian Ruggier, another Maltese army vet who serves as chief of planning and operations, told me, the MRCC radioed early in the morning with a report of migrants in trouble and directed the ship to a GPS point 30 miles off Zuwara, a beach west of Tripoli that is the most popular launch point for smugglers. Soon, Ruggier spotted a two-deck fishing boat packed with nearly 600 people. Suddenly, a second vessel overloaded with refugees emerged out of the mist, then a third, listing badly, two bilge pumps furiously pumping out water. ŌĆ£If this one had gone over, it would have been a tragedy,ŌĆØ Ruggier told me. ŌĆ£You had 500 people in the hold, and they would have had to climb out of a single two-square-foot hatch.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Ruggier jumped into one of the PhoenixŌĆÖs rigid-hulled inflatable boats (RHIBs) and raced for the vessel in distress. He had just reached the stricken boat when a fourth emerged out of the fog, and a fifth. My God, he thought. There must be 2,000 migrants in an area the size of two soccer pitches.┬Ā

Alerted by MRCC, support vessels began arriving. RHIBs from half a dozen ships darted among the refugee boats, distributing life jackets, taking on passengers, speeding across the water, off-loading them onto military ships and the private rescue craft. The Phoenix helped rescue 2,200 people, taking 372 aboard. By one oŌĆÖclock, the PhoenixŌĆÖs two decks were packed.┬Ā

Ruggier has intercepted pirates in the dangerous waters of the Gulf of Aden, off the coast of Somalia, and run rescue operations in Maltese waters, but never on this scale. ŌĆ£It didnŌĆÖt feel like a rescue,ŌĆØ he told me. ŌĆ£It was more like a military exercise.ŌĆØ

In late March, as the Catrambones were preparing for the six-month rescue season, I made my first trip to Malta, the densely packed island nation of 423,000 where they live. A bastion of Christianity during the Crusades and a vital Allied supply station in World War II, the former British colony has been reborn as a global financial center and a popular location for Hollywood filmmakers, who like its generous tax breaks and generically Middle Eastern look. ItŌĆÖs also smack in the middle of the European debate over migrants. As I taxied down to Marsa, the grimy commercial port, I passed a barracks surrounded by barbed wire and filled with sub-Saharan refugees. MaltaŌĆÖs government says it is sympathetic to the migrantsŌĆÖ plight, but after accepting about 19,000 in the past decade, it insists it has room for no more.┬Ā

I found Catrambone on the aft deck of the Phoenix, surrounded by the sounds of drilling, hammering, and scraping. The hull was getting a new paint job, and the crew was blasting off the rust. ŌĆ£As soon as the boat came back in October, we started doing work. ItŌĆÖs a big steel boat, and every single structure needs to be in perfect shape for the season,ŌĆØ said Catrambone, a shambling man with tousled black hair, a Lincoln-esque black beard, and a trace of Louisiana drawl. Recently, after the venture began attracting media attention he hired Robert Young Pelton, the veteran war journalist and author of The WorldŌĆÖs Most Dangerous Places, as a strategic adviser.┬Ā

He led me up a staircase to the upper aft deck and pointed out two RHIBs mounted snugly on metal cradles. ŌĆ£Feel this!ŌĆØ he urged, running his hand along one of the double-hulled, 20-foot dinghies, each equipped with two 70-horsepower outboard engines. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs got foam filling, so even if you puncture it, it will still float.ŌĆØ CatramboneŌĆÖs team had just moved the cradles to a lower position and installed two large pipes to guide the craft gently into the water. ŌĆ£Before, we were using a crane,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£In Force 4 winds, it was highly dangerous.ŌĆØ

The last time Catrambone threw himself into the business of boat renovation, the circumstances were rather different. In 2005, he was working as a freelance insurance-claims investigator after earning a degree in criminology at McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana. ŌĆ£He had this Volkswagen Passat with tinted windows, and a video camera, and weŌĆÖd go places and heŌĆÖd videotape people through his window,ŌĆØ recalls Templer, the chef, who lived in the same apartment building in New Orleans. Catrambone was ŌĆ£kind of neurotic,ŌĆØ Templer remembers. ŌĆ£He was like Kramer from SeinfeldŌĆöthis awkward, geeky type, but cool and laid-back at the same time.ŌĆØ

That September, Catrambone was on a job in the Bahamas when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans. Homeless, he set up shop in a three-cabin boat in a marina on Saint Thomas, in the U.S. Virgin Islands, and invited Templer and another dislocated friend to join him. With $20,000 in pooled compensation from FEMA, the trio leased a decrepit double-decker paddle-wheel boat and turned it into Cajun MaryŌĆÖs Riverboat Lounge, a floating bar and restaurant. ŌĆ£It was, in our way, our mourning for and tribute to a city we loved so much,ŌĆØ said Catrambone.┬Ā

Around that time, he got a call from G4S, a huge private security firm based in the U.S. It offered him a different sort of insurance-related assignment: locate medical treatment in Dubai for a U.S. contractor who had suffered a herniated disk there. That job led him within the year to northern Iraq, where insurance providers for big security companies were struggling to provide decent hospital care for contractors injured by roadside bombs. Catrambone assembled a network of secure hospitals in Iraqi Kurdistan, then did the same in Afghanistan. Soon he started his own war-zone insurance company, and Tangiers International, named for his favorite North African city, took off. By the time he was 26, he was a multimillionaire.┬Ā

At the end of 2013, Catrambone left Tangiers in the hands of his subordinates and began combing through online catalogs searching for a ship broker.

ŌĆ£Christopher is like a hurricane,ŌĆØ says Regina. ŌĆ£Standing in the eye, itŌĆÖs very calm for you, but for the people around you, he can be a disaster. HeŌĆÖs blowing around, people think he doesnŌĆÖt have a plan, but heŌĆÖs very disciplined when he needs to do something.ŌĆØ┬Ā

He ultimately tracked down the Phoenix in Norfolk, Virginia. It was love at first sight. Built in 1973 and originally used as a fishing trawler, then later as a scientific-research vessel, the ship had a steel hull, a deep draft, and a propulsion system built by W├żrtsil├ż, a Finnish company known for its icebreakers. ŌĆ£She was a badass little boat,ŌĆØ Catrambone says. He bought it on the spot for $1.6 million, spent $3.5 million more on a refit, and sailed it back across the Atlantic himself, with Cauchi at the helm and Templer in the galley. At one point the Phoenix struck something, possibly a container. ŌĆ£We heard a noise like boom-boom-boom, and then it stopped,ŌĆØ Cauchi recalled. He feared that the boatŌĆÖs new $1 million propeller had been destroyed. In fact the collision did break off a chunk, but Catrambone wasnŌĆÖt fazed. ŌĆ£He was a mad dog,ŌĆØ said Templer. ŌĆ£He was like, ŌĆśLetŌĆÖs go! LetŌĆÖs go!ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

When the Phoenix launched in August 2014, European diplomats and journalists were dubious. ŌĆ£They did not give us a lot of respect,ŌĆØ Catrambone said. ŌĆ£They suspected we were rogue Greenpeace-type activists causing trouble.ŌĆØ

CatramboneŌĆÖs doubts grew as well. ŌĆ£After five days at sea, we were frustrated,ŌĆØ he told me. ŌĆ£I was saying, ŌĆśThis is all a lie, the migrants are not even coming.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ Then, on day seven, the Phoenix carried out a double rescue of a fishing boat packed with about 300 Syrians and then an inflatable dinghy filled with sub-Saharan Africans. The MRCC took note and gave the Phoenix temporary command of three other vessels. MOAS had proved itself legit. By the time the mission ended in October, Catrambone said, ŌĆ£we didnŌĆÖt want to leave.ŌĆØ They stopped only because the boat was in dire need of repairsŌĆöand because the effort was draining the CatrambonesŌĆÖ finances.┬Ā

Indeed, last March, Catrambone doubted whether heŌĆÖd be able to deploy the drones in 2015. Earlier the previous year, he had struck a deal with Hans Georg Schiebel, owner of the Austrian military contractor Schiebel, for the pair of Camcopter S-100ŌĆÖs, pilotless mini-choppers that can fly 380 miles without refueling and are used by navies around the world. Schiebel initially wanted to sell the drones to him for $5.5 million, but Catrambone persuaded him to lease them for last yearŌĆÖs abbreviated three-month rescue season at $400,000 per month. ŌĆ£I told Hans, ŌĆśShow the world that this drone can be used for peaceful purposes,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ he recalled. ŌĆ£Hans said, ŌĆśDeal.ŌĆÖŌĆØ For this yearŌĆÖs season, Schiebel agreed to lower the monthly rate to $300,000 and kick in the last two months for free. But $1.2 million was still way too high for CatramboneŌĆÖs budget.┬Ā

Now, after burning through much of his fortune, Catrambone was looking for donations. Doctors Without Borders had given $1.6 million; GermanyŌĆÖs Oil and Gas Invest was paying for the boatŌĆÖs fuel. But he was short the $1.8 million for the drones. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre going to have to crowdfund for it,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£Organizations like Doctors Without Borders are just not into paying for drones.ŌĆØ┬Ā

A few weeks later came good news: Avaaz, a global activist organization, had agreed to kick in $500,000 for the two S-100ŌĆÖs. Catrambone would raise the rest just in time for rescue season.┬Ā

Now those S-100ŌĆÖs were proving to be critical assets. Hours after the drone launched from the PhoenixŌĆÖs helipad, Regina and I stood on deck, scanning the southern horizon. The Nafus Mountains rose up before us, about 30 miles away, wrapped in a dun brown desert haze. Regina guessed that the swells hitting the beaches of Zuwara would be about 18 inches highŌĆöperfect conditions for smugglers to launch their vessels.┬Ā

Approaching slowly across the water, a distant white speck came into our line of vision. Slowly, the dot took shape: a white inflatable dinghy, about 25 feet long, with a single outboard motor, packed with what looked like about 100 people.

The ship buzzed with anticipation. On the aft deck, Bryant, the doctor from Al-berta, zipped up his white protective suit and slipped on surgical gloves and rubber boots. The rest of the medical team, similarly attired, brought up 100 small blue bags from the hold, each containing socks, a towel, white coveralls, two bottles of water, and a package of protein bars. Cauchi, Ruggier, and three crewmen lowered an RHIB into the water and sped toward the tiny craft.

From several hundred yards away, I watched the rescue unfold: The RHIB approached the dinghy slowly, careful to avoid exciting those inside and causing the fragile craft to tip over. Cauchi, speaking English through a megaphone, reassured the migrantsŌĆöall of them, it seemed from my vantage point, sub-Saharan. The team passed out orange life jackets, loaded small groups onto the RHIB, and ferried them to the Phoenix. One by one, the migrants bridged the narrow gap between the boats and unsteadily boarded the bigger ship. Four young Somali women in head scarves, the first to set foot on the Phoenix, collapsed on the deck and clasped their hands in prayer. Soon the deck was filled with refugees from Somalia, Nigeria, Eritrea, Mali, and other blighted corners of the continent, 77 men and ten womenŌĆöweary, grateful-looking people whose ordeals over recent weeks and months could scarcely be imagined.┬Ā

With a blue MOAS baseball cap pulled low over her brow, Regina moved confidently among the refugees, bending down to reassure a worried-looking 15-year-old Ethiopian boy traveling by himself, searching for a Nigerian who had been punched in the eye during his voyage. The Phoenix was waiting for communications from the MRCC, which would either order it to take the migrants to a port in Sicily or tell it to remain in the area on patrol. ŌĆ£We have such a small group, we would rather continue,ŌĆØ Regina told me. ŌĆ£But we are in their hands.ŌĆØ┬Ā

ItŌĆÖs this work with the refugees that has been most fulfilling for Regina. In 2014, she shopped the markets of Malta for sacks of rice and vegetables and, working as TemplerŌĆÖs assistant, cooked hot meals in the shipŌĆÖs cramped galley for hundreds of hungry people. ŌĆ£We were using the cover of an oil container like a tray, and I was going up and down with the tray covered with rice and tomatoes,ŌĆØ she said. This year sheŌĆÖs spent dozens of hours in the onboard clinic. ŌĆ£I remember this Somali lady, she was with her two-and-a-half-year-old son,ŌĆØ she told me. ŌĆ£They had been 12 hours in an open boat. We took him from the dinghy, and he was not responsive.ŌĆØ Regina carried the boy to a bed, where a doctor administered an IV. Soon he was smiling, active, and playing with a Scooby-Doo doll and a toy Ferrari.┬Ā

As the crew awaited its orders, I fell into conversation with Abdisamat Mohammed Mahmoud, a 25-year-old Somali with a long, angular face who was leaning against the rail, staring into the sea. Born and raised in MogadishuŌĆöŌĆ£I cannot remember a moment of peace there,ŌĆØ he saidŌĆöhe had fled Somalia as a teenager and lived for six years in refugee camps in northern Kenya, where he taught himself English and Arabic. He and his wife had left to find work in South Sudan and, in April 2015, when the new country became too unstable, moved on to Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, with a plan to cross the sea to Europe. Smugglers packed them on a truck for the grueling weeklong journey through the desert to Libya. When they reached Tripoli, he was separated from his wife and held in a basement cell for 51 days while he waited for his family in Nairobi to wire $500 for the crossing.

ŌĆ£They came in two nights ago, and they said, ŌĆśLetŌĆÖs go,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ he told me. ŌĆ£They said, ŌĆśYou will go to Italy on a very nice boat. No problems.ŌĆÖ And they told us it would take about ten hours, but I knew they were lying.ŌĆØ The truck pulled up to the beach, and the migrants were ordered out, at gunpoint. ŌĆ£Most of the Somalis had never seen the water until that night. The women were crying,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£When I saw the boat, I was shocked. I thought, ŌĆśThey have cheated us.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ Unlike on the big fishing vessels, which usually have experienced captains, migrants aboard dinghies are generally told to aim for the Bouri Offshore Field and left to their own devices.┬Ā

The migrants, Mahmoud said, had pushed out to sea at around five oŌĆÖclock that morning. They carried a compass, which turned out to be broken, and had a half-liter bottle of water each. People cried, moaned, and prayed. ŌĆ£Some really thought that this was the last day in the world. I was telling them that we will be rescued, and that we will eat our breakfast in Italy,ŌĆØ he said.

Italy is obliged to keep the migrants until their applications for asylum are processed. ŌĆ£But they are not strict,ŌĆØ Casini said. ŌĆ£They don't always take fingerprints. So the migrants hope to slip through.ŌĆØ

TheyŌĆÖd been afloat for about eight hours when Malshak Adano, a 32-year-old Christian fleeing the violence in northeast Nigeria, saw the Phoenix in the distance and began shouting and waving. Then, as Adano himself told me, ŌĆ£a man with a megaphone said, ŌĆśDonŌĆÖt be afraid, weŌĆÖre giving you life jackets, weŌĆÖre going to protect you.ŌĆÖ I thought, God has answered my prayer.ŌĆØ

The next morning we passed Malta. The MRCC had dispatched orders to sail for Pozzalo, on SicilyŌĆÖs southern coast, and off-load our 77 passengers. A dozen Somalis crowded the starboard rail, silently absorbing their first view of Europe. Soon Mahmoud began peppering me with questions. Was Sicily an island? How far was it from the mainland? How long would it take to reach Rome? His first mission, he told me, was to find his wife. Once reunited they would make their way to Finland, which has a large Somali community, crossing the European UnionŌĆÖs generally porous borders. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖve heard that they have jobs there,ŌĆØ Mahmoud said.┬Ā

In fact, while Scandinavian countries have strong economies and have generally been more receptive than other nations to migrants seeking political asylum, a backlash is growing: in 2012, a parliamentary aide suggested on her blog that migrants wear armbands, and last May, a Helsinki city councillor called for the ŌĆ£forced sterilizationŌĆØ of African males.

We arrived in Pozzalo late in the afternoon. Mahmoud peered uneasily over the gangplank at the handful of Italian policemen milling around the port. Then, resigned to the uncertainty that awaited him, sure at any rate that the worst was behind him, he walked down the plank and was ushered to a medical screening tent. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre grateful to all of you!ŌĆØ Mahmoud shouted as he left the boat.┬Ā

What happened to the migrants next would depend largely on their resourcefulness, Gabriele Casini, a communications officer for Doctors Without Borders, told me as we stood on deck, watching. The Italian government is obliged by EU rules to keep them in the country until their applications for asylum are approved or rejected. ŌĆ£But they are not strict,ŌĆØ Casini said. ŌĆ£They donŌĆÖt always take fingerprints, so the migrants hope to slip through and reach Germany or the Scandinavian countries.ŌĆØ The two of us watched Mahmoud board a bus to a reception camp and gave him a final wave. ŌĆ£In these centers they are free,ŌĆØ Casini told me. ŌĆ£They can take off.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Perhaps Mahmoud would get to Finland after all.

As this latest group of refugees confronted their new lives in Europe, Europe continued to dither over how to deal with them. In June, EU leaders hashed out a modest scheme to share 60,000 Syrian and Eritrean asylum seekers over the next two years, though the United Kingdom refused to go along. Italy has warned that without a fair deal, it would start issuing temporary visas for migrants to travel beyond its borders. Meanwhile, as word of the dangers of the Mediterranean crossing spreads, migrants from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East are increasingly gravitating to an alternate route, traveling overland to Western Europe through Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans.┬Ā

ŌĆ£How pathetic is it that one motivated family can change something and all these entities donŌĆÖt?ŌĆØ Catrambone asked me one afternoon back in Sliema, Malta. The voyage was over, and heŌĆÖd picked me up at my hotel in his black Range Rover. As Buena Vista Social Club blared on the stereo, Catrambone navigated through the sun-splashed streets of this densely populated Maltese tourist town on our way to lunch at the Malta Royal Golf Club, a British-built oasis that dates back to the 1880s. It was a strange choice for a man who lately has dedicated himself to the refugees of the world. But Catrambone doesnŌĆÖt make any secret of his love of the finer things in life. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm a member, I think, but I just havenŌĆÖt had time to play golf,ŌĆØ he said as he dug into his jeans pocket and fumbled for his ID card at the entrance gate.┬Ā

Over cappuccinos on a terrace, we talked about the future of his rescue operation. With donations flowing to MOAS, the Catram-bones are ready to step back and pass on the operation to the crew. ŌĆ£We kickstarted it, and now with these guys on their own, the model is complete,ŌĆØ he told me. ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre saying, Take it over.ŌĆØ┬Ā

For the moment, Catrambone has returned to running Tangiers InternationalŌĆöhe recently purchased MaltaŌĆÖs biggest aviation insurance broker, making Tangiers the insurer of Air Malta and several other airlines. Business remains in his blood, itŌĆÖs clear, but he isnŌĆÖt ruling out another humanitarian project.┬Ā

ŌĆ£There is a level of civic-mindedness among millennials,ŌĆØ said Catrambone, one of the oldest members of that post-Gen-X generation. ŌĆ£They want free rice and open borders for everybody. They are thinking about solutions that benefit society as a whole, not themselves.ŌĆØ┬Ā

He stood up and stretched his long frame. ŌĆ£When you reach this point in your life, you realize what youŌĆÖre good at,ŌĆØ he said, displaying his customary mix of charming guilelessness and brash self-confidence. ŌĆ£I realized that I was good at doing the impossible.ŌĆØ

Contributing Editor Joshua HammerŌĆÖs book will be published by Simon and Schuster in April 2016.