In the first hours there was nothing, no fear or sadness, no thought or memory, just a black and perfect silence.

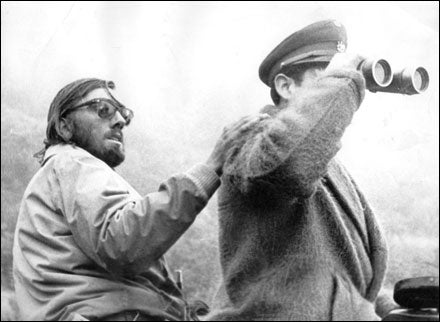

Q&A with Nando Parrado

To read a very personal Q&A with the hero of the Alive story, .Miracle in the Andes

Miracle in the Andes

Miracle in the AndesThen light appeared, a thin gray smear of daylight, and I rose to it like a diver swimming to the surface. Consciousness seeped through my brain in a slow bleed; I heard voices and sensed motion all around, but I could see only dark silhouettes and pools of light and shadow. Then, vaguely, I sensed that one of the shadows was hovering over me.

“Nando, podés oírme? Can you hear me? Are you OK?”

As I stared dumbly, the shadow gathered itself into a human face. I saw a ragged tangle of dark hair above deep brown eyes. There was kindness in the eyes-this was someone who knew me-but also something else, a wildness, a sense of desperation held in check.

“Come on, Nando, wake up!”

Why am I so cold? Why does my head hurt so badly? I tried to speak these thoughts, but my lips could not form the words. Carefully I reached up to touch the crown of my head. Clots of dried blood were matted in my hair; I felt rough ridges of broken bone beneath the congealed blood, and when I pressed down lightly I felt a spongy sense of give. My stomach heaved as I realized that I was pressing pieces of my skull against the surface of my brain.

“Is he awake? Can he hear you?”

“Say something, Nando!”

“Don’t give up, Nando. We are here with you. Wake up!”

All I could manage was a hoarse whisper. Then someone spoke slowly in my ear.

“Nando, el avión se estrelló! Caimos en las montañas.”

We crashed, he said. The airplane crashed. We fell into the mountains.

“Do you understand me, Nando?”

For more than two days I’d languished in a coma, and I was waking to a nightmare. On Friday the 13th of October, 1972, our plane had smashed into a ridge somewhere in the Argentinian Andes and fallen onto a barren glacier. The twin-engine Fairchild turboprop had been chartered by my rugby team, the Old Christians of Montevideo, Uruguay, to take us to an exhibition match in Santiago, Chile. There were 45 of us on board, including the crew, the team’s supporters, and my fellow Old Christians, most of whom I’d played rugby with since we were boys at Catholic school. Now only 28 remained. My two best friends, Guido Magri and Francisco “Panchito” Abal, were dead. Worse, my mother, Eugenia, and my 19-year-old sister, Susy, had been traveling with us; now, as I lay parched and injured, I learned that my mother had not survived and that Susy was near death.

When I look back, I cannot say why the losses did not destroy me. Grief and panic exploded in my heart with such violence that I feared I would go mad. But then a thought formed, in a voice so lucid and detached it could have been someone whispering in my ear. The voice said, Do not cry. Tears waste salt. You will need the salt to survive.

I was astounded at the calmness of this thought and the cold-bloodedness of the voice that spoke it. Not cry for my mother? I am stranded in the Andes, freezing; my sister may be dying; my skull is in pieces! I should not cry?

Do not cry. . . .

The story continues in the May issue of ���ϳԹ���.