Over the past year, highly organized, well-funded teams pulled off an astounding number of firsts, sending a Hollywood director to the deepest spot in the ocean, landing a drone on Mars, and equipping a skydive from the edge of space. Presented here are our adventurers of the year. Enjoy!

Kilian Jornet

Diana Nyad

James Cameron

Erden Eruc

Lakpa Rita

Felix Baumgartner

Bobak Ferdowsi

Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner

Dave Mossop

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Ultramarathoner Kilian Jornet

Spanish ultramarathoner Kilian Jornet is the world’s best at only 25

Kilian's Quest

Kilian Jornet making tracks near Chamonix

Kilian Jornet making tracks near Chamonix Dakota Jones on the Colorado trail by Molas Pass.

Dakota Jones on the Colorado trail by Molas Pass. Anton Krupicka atop Colorado’s 14,728-foot Grays Peak

Anton Krupicka atop Colorado’s 14,728-foot Grays PeakJust after three in the morning last September 18, Spanish runner Kilian Jornet set out from the small Italian town of Courmayeur, at the base of 15,771-foot Mont Blanc, and headed for France. Jornet, who at 25 is the world’s top ultramarathoner, was wearing only running shoes, spandex tights, and a windbreaker. On his five-foot-six, 125-pound frame he carried a small backpack with crampons, some climbing rope, water, and a few other essentials.

Over the next six hours, Jornet ran, scrambled, and climbed more than 12,000 feet up Mont Blanc’s south face. After running past two common stopping points—the Monzino hut, at 8,402 feet, and the Eccles bivy, at 12,631—he traversed along the Innominata Ridge, a technical section of mountain that features an expanse of glacier with a 60-degree slope, where Jornet donned his crampons and used his ice ax. Most climbers who ascend via the Innominata do so over three days, carrying tents and food. Just getting to the summit can take as long as 20 hours, and it’s technical enough that guides often won’t take clients up it. Jornet reached the summit at 10:15 A.M., then took two more hours to run and scramble down the French side to Chamonix. All told he covered more than 26 miles and 24,000 feet of elevation change in eight hours and 43 minutes.

“What Kilian did on the Innominata Ridge is pioneering a new style of alpinism,” says Nebraska ultrarunner Anton Krupicka, 29, a two-time winner of Colorado’s Leadville 100. “To solo that stuff in eight hours—it’s three, four times as fast as anyone’s ever done it. It’s crazy.”

Indeed, crazy may be the best way to describe this hybrid of running and climbing, which doesn’t really have an established label yet. In the past couple of years, Jornet and a cadre of other top ultrarunners have begun using small amounts of alpine equipment to make record-breaking solo ascents of mountains only recently dominated by speed climbers like Swiss mountaineer Ueli Steck and American Chad Kellogg. Last summer, Jornet and Colorado native Andy Anderson, 36, traded speed ascents on Wyoming’s 13,770 Grand Teton, dipping below three hours on a route that often takes 20. In October, Krupicka set a new speed record on Wyoming’s 13,804-foot Gannett Peak. Then, in September, Jornet ran Mont Blanc. So what to call them? Ultrarunners who climb? Climbers who run?

“In the past those were separate sports,” explains Colorado runner Dakota Jones, 22, another of Jornet’s peers. “Now they’re not.”

Traditionally, ultrarunning is defined by distance, not altitude. The guiding mantra is masochism, embodied by the sport’s biggest names, including Scott Jurek, 39, a vegan who has won some of the most grueling 100-mile races multiple times, and Dean Karnazes, 40, known for running 50 marathons in 50 days in 2006. Ultra-distance events are more popular than ever, thanks in part to Christopher McDougall’s bestselling book, : a record 36,000 people participated in them in the U.S. last year.

Mountainous courses have long been a mainstay of competitive ultrarunning—the Western States 100, which climbs 18,000 vertical feet in California’s Sierra Nevada, was first held in 1977. But Jornet and others aren’t just running on mountain trails; they’re charging up peaks along mixed-terrain routes that feature sections where most climbers tie into ropes and swing ice axes. Jornet was born to lead the effort. Raised in the Spanish Pyrenees, he grew up running the trails around his house and backcountry skiing. When he was 18, he took up mountain racing and created a long list of ski-mountaineering and ultrarunning events he wanted to win. Buoyed by a fast, light frame and a strong aerobic capacity—most of his 125 pounds are in his legs, and he has a VO2 max of 92, among the highest ever measured—he quickly started crossing races off his list. He won a series of World Cup ski-mountaineering championships and then, in 2008, at age 21, dominated the prestigious 103-mile (UTMB) race. He has been all but unstoppable since, winning Europe’s SkyRunning mountain ultra-distance series five times and the UTMB two more times, along with the Western States 100 and the Pike’s Peak Marathon—all while crushing it on the ski-mountaineering world-championship circuit.

In 2011, Jornet decided he needed a new challenge, so he focused on solo climbing. He had no desire to become a classic climber; he wanted to develop alpine fundamentals while training his body to tolerate extreme exertion at high altitudes. After Jornet’s Mont Blanc traverse, the alpine-climbing world took note. Steck, himself an accomplished trail runner, marveled at what he might be able to accomplish with Jornet’s endurance. “Can you imagine what I could do if I had the physique of Kilian?” he told Rock and Ice. Still, Steck doesn’t consider Jornet a true peer. “He’s an incredible endurance athlete,” says Steck. “But he’s not an alpinist yet.” For his part, Jornet resists labeling. “I don’t think I do this or that sport,” he says. “I basically just enjoy being fast in the mountains.”

He’s not the only one, which is why some organizers in the U.S. are looking to capitalize on Jornet’s buzz by launching a new generation of mountain footraces. Big Sky, Montana, will hold a 50K mountain run this September, and Jones is trying to get the U.S. Forest Service to approve a similar competition in Telluride, Colorado. Slated for August, the race would include steeper climbs and rougher terrain than events like the Western States. Still, Jornet and his elite peers are more interested in solo speed records, which means their most impressive efforts over the next few years will take place somewhere in the high backcountry, without spectators.

That’s part of the appeal. Jornet and his counterparts are exciting precisely because it’s hard to say what they might do next. Jones is working on his ice climbing. Last year, Krupicka tried resoling his New Balance trail runners with the sticky rubber used on climbing shoes. This summer he’s planning a 90-mile traverse on the Continental Divide in Colorado that will take him over 14 different 14,000-foot peaks. And Jornet has turned his attention to a project he calls : a three-year series of ascents that will include speed-record attempts on peaks ranging from Argentina’s Mount Aconcagua and Alaska’s Denali to, eventually, Everest, via the South Col, in 2015.

“I think he’ll go really fast,” Krupicka says, “and the mountaineering community will be forced to pay attention.”

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Swimmer Diana Nyad

The swimmer continues her quest to swim from Cuba to Florida

FOR THE PAST two summers, Diana Nyad has generated worldwide attention for her dogged attempts to swim the 103 miles from Havana, Cuba, to Key West, Florida. But the most amazing thing about her quest isn’t the mileage she racked up in her four failed bids but the fact that, at 63, she wouldn’t think of giving up. “I’m either going to die or make that swim,” says the Los Angeles–based Nyad, who plans to try again this summer. Nyad, who has been long-distance swimming for much of her life (she swam around Manhattan in 1975 and from the Bahamas to Florida, a distance of 102 miles, in 1979), says each failure drives her more intently to succeed. “We learn something every time we go out,” she says:

1. Eddies suck.

The Gulf Stream is 65 miles wide and flows like a river, at up to five knots, due east. And like any river, it has eddies—massive ones, as large as 50 miles across. “They’re difficult to predict and difficult to get out of,” says Nyad, who swims at roughly 1.5 knots.

2. Man-of-war stings hurt.

“You get nauseous, and it feels like an asthma attack,” she says.

3. Whitetip sharks are like honey badgers.

Unlike tiger and lemon sharks, whitetips are impervious to the fish-repelling electrical field generated by the device her chase kayak drags alongside her. “They don’t care about it at all,” says Nyad, who’s been buzzed but never bitten.

4. Box jellyfish are the worst.

“They’re the perfect lethal weapon,” says Nyad of the sugar-cube-size blobs. Their toxin attacks the nervous system, causing nausea, breathing problems, and even death. Last August, Nyad wore a full-body swimsuit, pulled a nylon stocking over her head, and had a leading box jelly researcher aboard her guide vessel with salves at the ready. Still, her lips were exposed. “I swam for 51 hours,” says Nyad, “and I was stung two nights in a row.”

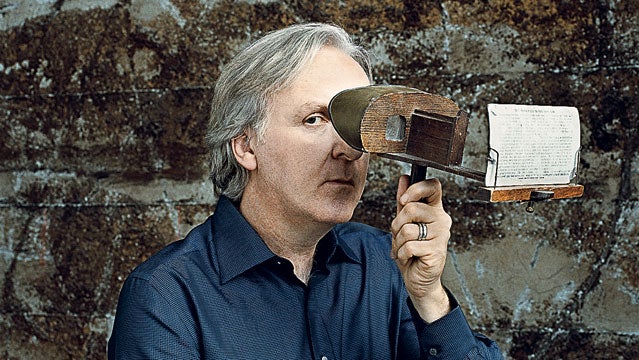

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Director James Cameron

Changing the way the adventure world works

On March 26, 2012, director James Cameron piloted his mini sub, the Deepsea Challenger—which he designed with engineer Ron Allum—to the deepest spot in the ocean, the 6.8–mile-down Mariana Trench. It was only the second time mankind had reached that depth, after Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard made the trip in 1960 in the U.S. Navy’s hollow-steel bathyscaphe Trieste. Bold projects like this used to be possible only through government funding. Now the adventure world is dominated by individuals and companies with deep pockets.

These were the stages of James’s deep sea dive:

Sea level: Two hundred miles off the coast of Guam, Cameron’s support vessel winches the 24-foot Deepsea Challenger into the Pacific.

650 feet: Descending at a rate of eight feet per second, the Challenger moves through the sunlight zone, where most ocean life resides, and into the twilight zone, where light fades and bioluminescent creatures like lanternfish live.

13,000 feet: Lights out—Cameron enters the pitch-black abyssal zone.

19,700 feet: Three-quarters of the ocean floor lies at this depth. The only deeper points are its trenches.

Touchdown: Two hours and 36 minutes after beginning his dive, Cameron arrives at 35,756 feet, where water pressure is 16,000 pounds per square inch. Before collecting sediment samples for analysis, Cameron sends out a tweet: “Just arrived at the ocean’s deepest pt. Hitting bottom never felt so good.”

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Circumnavigator Erden Eruc

After 1,026 days circumnavigating the world, former software engineer Erden Eruc returns home

He wasn’t the first to complete a human-powered global circumnavigation—that title belongs to Briton Jason Lewis, who completed his 46,000-mile voyage in 2007—but the 51-year-old Turkish-American’s silver-medal effort required a level of mental endurance that was borderline pathological. Last July, after 1,026 days and 37,472 miles of hiking, biking, and boating, Erdun Eruc, a onetime software engineer who now lives in Sydney, returned to his starting place, Bodega Bay, California. He had battled the Pacific in a rowboat for 419 days, biked across Australia, rowed the Indian Ocean (a first), trekked across Africa, and rowed from Namibia to Venezuela to the Gulf Coast. After cycling the final 2,389 miles from Louisiana to California, Eruc quietly returned home and faced the shock of reentering everyday life.

“I felt isolated, like I didn’t belong,” he says. “For years this journey defined my existence.” He also burned through most of his life savings. Still, the prospect of financial ruin hasn’t prevented him from plotting even bigger adventures. “If I can finance it, I won’t hold up the future trying to pay back the past,” he says. His next dream? To climb the six highest peaks on six continents. His initial plan calls for making separate self-powered trips to each summit. Look for a small boat rowing toward Everest soon.

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Sherpa Senior Guide Lakpa Rita

Sherpa senior guide Lakpa Rita has been quietly and expertly rescuing Everest climbers for the past 20 years

16

Number of times Lakpa Rita has summited Mount Everest

The Sherpa people of Nepal have only seven first names, which are given for the days of the week. This is just one of the many factors that cause Westerners to overlook their monumental efforts in the Himalayas. But here’s one name to remember: Lakpa (Wednesday) Rita, a 47-year-old senior guide from Alpine Ascents International. During every major Everest event of the past 20 years—including the 1996 disaster, when he saved a not-quite-dead Beck Weathers by helping him down from the South Col—Lakpa Rita has been aiding and rescuing the injured and incompetent alike.

“He doesn’t like to talk much about rescues,” says Everest guide Garrett Madison, who was with Lakpa on Everest last season. “He’s very quiet about his accomplishments.”

“I remember a rescue that I got a lot of recognition for in 2007, when we found a semiconscious Nepali woman at 27,300 feet,” says longtime Everest guide and ���ϳԹ��� correspondent Dave Hahn. “We started dragging this woman down the hill, and Lakpa Rita came up from the South Col. He jumped in and basically left me struggling to keep up. There are probably a lot of other rescues that I don’t even know about.”

Last September, on 26,781-foot Manaslu in the Nepalese Himalayas, a massive avalanche wiped out Camp III, killing 11 climbers. Lakpa, who has summited the highest peaks on all seven continents, was the first person out of his tent in Camp II, rushing to administer first aid to survivors, search for bodies in the avalanche debris, and help coordinate the evacuation of nearly 20 wounded climbers. As usual he faded into the background in the ensuing media frenzy, leaving the sound bites to Western climbers. He did not respond to interview requests.

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Supersonic Man Felix Baumgartner

Changing the way the adventure world works

Pilot Felix Baumgartner of Austria sits in his capsule during the preparation for the final manned flight of Red Bull Stratos.

Pilot Felix Baumgartner of Austria sits in his capsule during the preparation for the final manned flight of Red Bull Stratos.On October 14, Felix Baumgartner, the Austrian skydiver, stepped out of a steel capsule and fell to earth from the stratosphere, topping the previous record for highest parachute jump, which was set by Air Force colonel Joe Kittinger in 1960. Bold projects like this used to be possible only through government funding. Now the adventure world is dominated by individuals and companies with deep pockets.

Here’s a breakdown of Baumgartner’s jump:

127,852.4 feet: After a massive helium balloon lifts him 24 miles high, Baumgartner opens the hatch to his eight-foot-diameter capsule and launches into the stratosphere.

91,316 feet: Fifty seconds into free fall, Baumgartner reaches his top speed of 843.6 miles per hour and becomes the first person to break the sound barrier with his body, that’s caught on amateur video from the ground.

75,000 feet: Baumgartner enters into an uncontrolled flat spin—one of the greatest concerns going into the mission, since G forces can cause blackouts. After 13 seconds he regains control.

8,400 feet: Baumgartner pulls his chute after four minutes and 20 seconds of free fall.

Touchdown: Forty-five miles east of Roswell, New Mexico, Baumgartner lands safely, drops to his knees, and raises a hand in triumph for the cameras.

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: NASA Engineer Bobak Ferdowsi

NASA systems engineer Bobak Ferdowsi on the Mars rover and the mohawk

NASA lost much of its luster when it terminated the manned space shuttle program in August 2011. But when the Jet Propulsion Laboratory landed a car-size rover in the Red Planet’s Gale crater last August—complete with cameras beaming back HD photos—it captivated the nation in a way the administration hasn’t since the Apollo program. And while there were 40 people in the Pasadena, California, control room helping monitor the rover, only one became an Internet sensation and the de facto spokesman for the ten-year, $2.5 billion project: Bobak Ferdowsi, 33, an Iranian-American systems engineer whose mohawk went viral. We spoke with Ferdowsi, who sports a different haircut for each milestone in the project, about what it’s like to inherit the mantle of great explorers.

OUTSIDE: The media latched onto you because of the mohawk. Did the rest of

the team wish they had a funky hairstyle?

FERDOWSI: I don’t think anybody else wanted that haircut. But, in a way, they all had a hand in it. My bosses sent out an e-mail before one of the practice landings and asked the team to vote on the style I should have. I told them their decision was nonbinding.

Past explorers lost life and limb. What are you risking?

Even now, if we’re not cautious, we could end the mission. That’s why we take our job so seriously. The rover is a billion-dollar national resource that we’ve put on the surface of another planet.

What’s the goal?

We want to get to the foothills of Mount Sharp, which is this gorgeous mountain on the edge of the crater we landed in. One of the most amazing things was that first picture on Mars—you could see it in the distance. We’ll have to do some driving to get there. So far we’ve gone only 700 meters.

So there’s nobody raising hell with the rover like a drone go-kart?

There’s nobody driving it around like a rally car, no.

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Mountaineer Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner

Austrian mountaineer Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner won’t stop trailblazing

In 2011, Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner solidified her mountaineering legacy by becoming the first woman to bag all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks without supplemental oxygen. She followed that up in 2012 by completing the hardest line of the season from Everest Base Camp: the rarely attempted Scott Route up 25,790-foot Nuptse, first ascended in 1979 by a team of British climbers. In May, the 41-year-old Austrian joined German David Göttler on the brutally exposed, avalanche-prone line, tackling it in four days. It was just the third successful attempt up the route, which ascends a 5,791-foot wall, and they did it without the aid of oxygen or high-altitude porters. They were also just the 19th and 20th people to reach Nuptse’s main summit. This summer, Kaltenbrunner sets her sights on Denali, most likely via the difficult Cassin Ridge route and the highly technical Moose’s Tooth. “It’s been a dream for me to climb in Alaska,” she says. “I’m very much looking forward to it.”

���ϳԹ���rs of the Year: Filmmaker Dave Mossop

The Canadian filmmaker captivates with his breakout ski film, All.I.Can

Into the Mind

The most impressive ski film of the past year had no plot or script. It was mostly a rambling collection of scenes—lava flows, changing seasons, huck shots—with an intermission for a climate PSA from Aspen Skiing Company scold Auden Schendler. That might not sound so fun, but , from 33-year-old Dave Mossop and his production house, , became a breakout hit at festivals from Banff to Mountainfilm thanks to its stunning cinematography. The street scene featuring JP Auclair grinding on railings and skidding across pavement in Trail, B.C., has been viewed more than a million times on Vimeo alone, and the film’s climax, in which Canadian skier Kye Petersen bombs down Canada’s Mount Ossa, is simply breathtaking.

Mossop, of Whistler, British Columbia, attributes his success to the stagnancy of the ski-film industry. “Audiences seem willing to accept new things,” he says. Mossop has big ambitions for his next film, a ski and travel flick titled that promises a surreal journey through the Himalayas, Bolivia, and the Canadian Rockies. “We’re moving into a world of dream states,” he says. “We’re creating a filmic reality where whether we’re in a real place or not is insignificant.”