Looking over his daughter’s first captured fox in the film , Rys Nurgaiv says: “To be sure, this is no ordinary bird. This was a tough endeavor.”

Nurgaiv Aisholpan, a Kazakh teenager living in rural northwest Mongolia, made headlines around the world in 2014 when, at the age of 13, she became the youngest winner of the region's annual . She was also the first female eagle hunter to compete.��

Aisholpan grew up with the sport: her father is a master eagle hunter. The Eagle Huntress, an upcoming documentary directed by Otto Bell and narrated by Daisy Ridley, follows her for about a year, from the early training days and the capture of her eagle, and culminates in her first successful hunt. The movie, released in New York and Los Angeles on November 2, and is being rolled out to other cities .��

Eagle hunting has been passed down from father to son for generations and remains a staple element of Kazakh culture. Hunters capture an eaglet from the nest before they can fly away, then spend three to four months training and developing a close bond with the bird. Once trained, the hunter and his (the field is dominated by men) eagle work as a team for seven years, when the eagle is then released to the wild to repopulate.��

For many in the eagle-hunting community, Aisholpan's desire to break into this traditional boy’s club was seen as an affront to their way of life: there have only been a handful of documented female huntresses in history. “Women are supposed to stay indoors and quarrel for the gifts after parties,” one male eagle hunter says in the film, “while men are meant for the outdoors and we quarrel for the catch.”

Far more interesting than these elders, however, are Aisholpan’s parents, Nurgaiv and Almagul. Both are concerned with the community's disapproval of their daughter’s ambition, but they are uncompromisingly supportive. “I believe it is a woman’s right to choose—there are so many strong eagle hunter men,” Almagul explains early in the film.��

We spoke with Bell about his relationship with Aisholpan and her family, the challenges of filming birds of prey in action, and the film's impact so far.

OUTSIDE: Aisholpan’s parents really opened up to you. How did you build a relationship with them?

OTTO BELL: What I would call the basic rapport came really quickly because the Kazakh nomads of northwest Mongolia, they're very warm and welcoming. Even if you stopped and asked for directions, you're probably going to have tea, and the food is laid out, and it's just very welcoming by nature. But then in terms of that next level, that just honestly took time. I did probably seven or eight visits over the course of the year. I would go to school with Aisholpan, and they could see I was around for the long haul. Over time, they could see that my interest in their family and their history was genuine.

The first visit you had with the family was also the day you filmed the scene where Aisholpan captures her eagle from a nest on a cliff around a hundred feet off the ground near her home.��

It was kind of thrown together, but we also planned out the angles, because we knew we were only going to get one chance. So we put three angles on it. I had my cameraman Chris Raymond with me and he was at the bottom of the cliff filming the wide shots.��Asher Svidensky, who took of Aisholpan that inspired the documentary, was also with me on that first trip.��At that time, he had never shot video, but he did have his Canon DSLR, so we put it onto video mode and I said, “Look, just keep it steady and keep it in focus.” He and I went up to the top and we filmed Aisholpan getting the rope on so her father could hold her as she climbed down to the nest, and then we're like, “Okay wait, wait,” you know, like the universal hands up sign for wait, and then we scrambled down the side of the cliff to a ledge that was next to the nest, and that's how we got the sideways angle. And then, finally, we put a GoPro underneath her cardigan—that's when it became less about me making a film. It actually became about me telling her story because I was there for that first step.

The hunting scene is so powerful. How did you set up the shots you wanted while not interfering with the hunt?

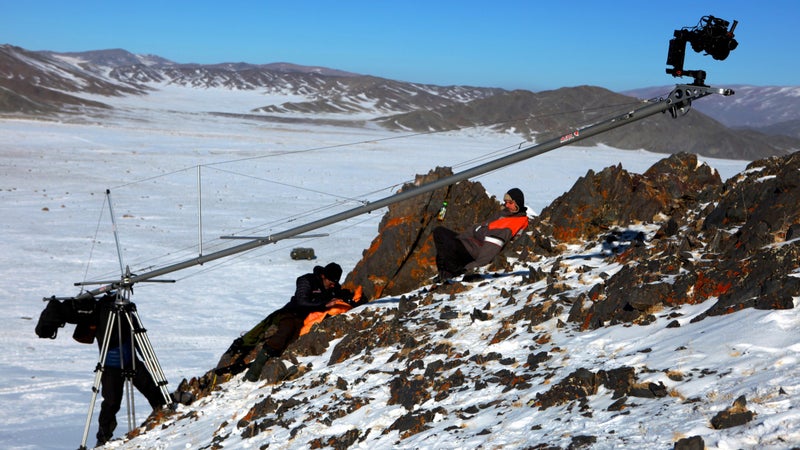

That sequence was really tough, because it was so cold. It got down to about minus 50 degrees. We could only film for about two or three hours a day when the sun would come up over the mountains and it would warm up to about minus 20, minus 25. That's when the equipment would come back to life, LCD screens would work, we could get the drone up in the air, your hands would stop sticking to metal. Things like that.��

We set aside five days to film that final sequence and it ended up taking us about 22 days. It was hard, it was tough, but the thing that saved us, honestly, was her father. His ability to read the landscape and to understand what was likely to happen was amazing. I mean it was almost eerie at times—like he was almost preternatural. He would position us, he would point to where we should set up, like if anything is going to happen in this gully, if there's anything in here, it's likely going to pop out here, so you should be over there.

What has surprised you the most about the public's reaction to the film?

I've been really pleased with how younger audiences have responded to it. The thing that's really surprised me though has been how quickly people see the universal messages in it. I thought I was making quite an exotic film about a little-known tradition in a foreign language. I didn't think that people would just go, “Oh yeah! It's a story about a dad and his daughter,” or, “Oh yeah! Girls should be able to do whatever they want.”

Was there pushback from the elders after Aisholpan caught her first fox? Did they believe that she had actually done it?

I wanted to finish the film with her private victory, simply because she didn't need the community's validation to pursue her dream. Their acceptance wasn't the crucial factor in her happiness. She just wanted to go out and hunt successfully with her dad. That private victory was important, but since that happened, yes, she's been out with her dad and his friends hunting and they spread the word that she's legitimate, that she's a genuine article, that she can hunt successfully.��

Do you think she’ll continue to be an anomaly or have you seen interest from other women who want to practice eagle hunting?

She was asked to lead the Kazakh New Year parade in recognition of what she's accomplished, and at this year's eagle festival, which just happened in October, there were actually three more eagle huntresses there. I don't know if they all competed, but it's happening.��

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.