IT WAS FEBRUARY 2004 IN SUNNY BAGHDADback before everything totally hit the fan in Iraq and nation building still seemed like an iffy but viable concept. My friend Jeff and I were in our office at the city’s convention center, a cavernous building tucked inside the Green Zone, the walled-off seat of power, money, and assumed security where the United States government based its postwar reconstruction.

Babylon by Bus

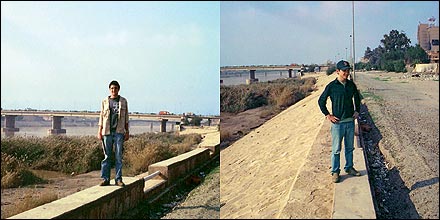

The Jordan-to-Iraq Express, stopped for repairs outside Fallujah, Iraq.

The Jordan-to-Iraq Express, stopped for repairs outside Fallujah, Iraq.Babylon by Bus

Children on the streets of Sadr City.

Children on the streets of Sadr City.Babylon by Bus

Children and aid workers on the streets of Sadr City, one of Baghdad's poorest neighborhoods.

Children and aid workers on the streets of Sadr City, one of Baghdad's poorest neighborhoods.Babylon by Bus

All aboard for Babylon!

All aboard for Babylon!Babylon by Bus

Children on the streets of Sadr City.

Children on the streets of Sadr City.Babylon by Bus

Aid workers on the streets of Sadr City.

Aid workers on the streets of Sadr City.We had shown up in Baghdad a few weeks earlierunannounced, carrying backpacks, and lacking any real qualificationshoping to volunteer somehow. On our first day of job searching, we’d lucked into work with the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), the U.S.-led agency that ran the reconstruction from just after the invasion’s end, in May 2003, until Iraq’s interim government started taking over, in June 2004. Our assignment was to help oversee the distribution of humanitarian aid, but on this afternoonafter making our runswe were back in the office writing field reports.

That’s when an Army private walked in and introduced himself. His name was Ricky Skyler, but all his friends back in Arizona called him Sky. He spoke in a slow, low, mumbly monotone. After a little small talk, he got to the point.

“All the people in my unit suck,” he said. “I hate the Army. Do you guys have access to any drugs?”

“Huh?” It was a bold question.

“Drugs… You guys look like you might have some.”

We did? Well, we did.

“Uh, we don’t really have any good drugs,” Jeff said. “Just a little Valium, some weird painkillers… but we could get hash in a couple of days, I guess.”

“I’m a straight candy raver,” Sky said.

We didn’t know that was still popular.

“Out west, there’s still these crazy raves,” he went on. “Popping pills in the desert under the stars with my girl. That’s my shit.” Hmmm.

We liked this guy. His honesty was refreshing, and he seemed totally helpless. Medium-tall and thin, with dirty-blond hair and an innocent baby face, Sky was a normal 20-year-old who’d joined the Army and ended up going nuts. He hated the military, with its power-hungry sergeants bossing him around.

Jeff gave Sky some painkillers; I gave him Valium. Then Jeff took him to meet an Iraqi we knew who could get just about anything. That was day one. By day three, Sky was a full-fledged member of our crew. In return for the drug hookup, he treated us to huge meals at the al-Rashid Hotel’s restaurant, one of the Green Zone’s finest dining establishments. Sometimes he’d blow his whole paycheck.

Like us, Sky hung out at malls in high school, and we bonded over appreciating the great Arizona shopping palaces. Jeff and I had been through a few when we visited the state to play poker at Casino Arizona.

“Guess I’m the only cool soldier around, huh?” Sky asked Jeff one day.

“Well,” Jeff said, “you’re definitely the only one to just walk up and ask for drugs.”

Adapted from Babylon by Bus, by Ray LeMoine and Jeff Neumann (with Donovan Webster), to be published August 8 by The Penguin Press.

DURING OUR THREE-MONTH adventure in Baghdad, Jeff and I were often asked, “What the hell are you guys doing here?” The answer was complicated, but for starters, we sincerely wanted to go over there and help. The less exalted motive stemmed from our shared hatred of the New York Yankees.

Jeff and I, both in our twenties, are Boston-area college dropouts. We’re also Red Sox fans to the point of painful cliché, and since 1999 the Sox had provided us with decent money selling YANKEES SUCK T-shirts outside Fenway Park. A friend and I started making them that year; they’ve been a Fenway staple ever since.

For Jeff and me, the actual road to Baghdad had started in section 336 of Yankee Stadium on the night of October 16, 2003Game 7 of that year’s American League Championship Series between the Sox and the Yankees. The Sox were ahead going into the eighth inning. But then the Yankees rallied to tie, and in the bottom of the 11th the Pinstripes prevailed when Aaron Boone blasted a game-winning home run into the left-field stands, not far from where we sat.

The next afternoon, hungover and heartbroken, Jeff and I woke up in our Brooklyn loft. (Weary of Boston’s post-college social scene, we’d migrated to New York in 2003.) We retreated to the rooftop, which offered a great view of Manhattan.

“Must we endure another painful winter?” Jeff said. “I can’t. I have to leave.”

“New York?”

“The whole East Coast. America, even. I’m over it. I don’t know. Maybe go to the Middle East.”

For the past few years, thanks largely to our YANKEES SUCK income, Jeff and I had used the off-season to travel. We’d already been to some 60-odd countries each, but we’d grown tired of the Lonely Planet vibe. We never wanted to meet another Dutchman who liked Goa trance music and Ecstasy; we were sick of Thailand’s fake exoticism, Guatemala’s “culture,” and beaches in remote backpacker hot spots.

Having grown up in the D.C. area (Jeff) and Massachusetts (me), we have politics in our blood, so we wanted to go somewhere that mattered, a place where we could observe, firsthand, that holographic concept known as the Global War on Terrorism. Thus, through a combination of political curiosity, a willingness to work for nothing, and our enduring love of bad schemes, we got serious about going to Iraq. I recall saying to Jeff, “We can stay home and do nothingblow money at bars and sleep until noon. Or we can go see what interests us most.”

“You’re right,” he said. “Hemingway didn’t stay home. Orwell didn’t.” A date was set. We’d spend New Year’s 2004 in Tel Aviv, then press on to Iraq.

ON JANUARY 16, 2004, we boarded a bus in Amman, Jordan, bound for Baghdad. At the Iraq border, we were surprised to learn there wasn’t any securityno razor wire, no armed guards. Inside a grim little blockhouse, a pair of bored-looking passport clerks moved through the harshly lit room as if underwater. They stamped our passports without looking up, and away we rolled. After 24 hours of intermittent engine failures and sightseeing opportunities that included burned-out tanks, our voyage ended around 4 p.m. at Baghdad’s central bus station.

There, chaos ruled. Hundreds of minibuses were coming and going across a huge swath of pavement. As we grabbed our luggage, a female Iraqi who spoke English offered to share a cab. We told her we wanted to go to the al-Rashid, a hotel inside the Green Zone that was one of the few places we knew by name.

“That’s Saddam’s house,” she said. “Now, Mr. Bush house!” Her head was wrapped in a flowery scarf, face showing. She looked flinty, but she was laughing at her own joke.

Our taxi let us out at one of the GZ’s major checkpoints, the al-Rashid Gate. What had once been an ordinary road was now a no-man’s-land, protected by a machine-gun tower, nests of looping concertina wire, and mega-sandbags called Hesco barriers. Through an opening in the loops of wire, a youngish blond woman emerged. She saw us and came over.

“Backpackers in Baghdad?” she said with a giggle. “Wow, now I’ve really seen it all. Where are you guys going with those big packs?”

We explained our mission. “Can we stay at the al-Rashid?” Jeff asked.

“No,” the woman said, smiling at our sublime ignorance. “It’s been closed since Paul Wolfowitz was rocket-attacked there last fall. C’mon, I’ll take you guys to a hotel.”

The woman, whose name was Marla Ruzicka, had a driver, a casually dressed Iraqi man, and we all packed into his car. Before long we were stuck in traffic on a bridge that spanned the mud-brown Tigris River, the waterway that meanders through Baghdad’s center. Marla told us she’d been in the city since the U.S. invasion and was in Afghanistan before that. She was 27 and had grown up in California. She was the founder of a nongovernmental organization (NGO) called the Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict (CIVIC), whose job was keeping track of civilian casualties in war zones.

“How much money do you want to spend on a hotel?” she asked.

“Cheap,” Jeff replied.

Marla led us to an affordable place called the al-Rabei. After settling in, we cracked open a bottle of whiskey. That night, from our room’s balcony, Baghdad looked like a sparsely populated desert, thanks to the electrical grid being down. Two Black Hawk helicopters circled in the dark sky, reminding us that this was indeed a war zone.

“Mission accomplished, amigo,” I said to Jeff. “From a Brooklyn roof to a Baghdad balcony.”

“Cheers,” Jeff said. We passed out soon after that.

THE NEXT MORNING, we woke up to an extremely loud explosion. A suicide car bomber had hit the Assassins’ Gate checkpoint, which is about a half-mile away from the al-Rashid Gate. Curious, we got dressed, hiked to the scene, and saw things we wished we hadn’t. There was a deep crater, smoldering cars, a blood-splattered passenger bus, and body bags filled with corpses. Twenty-five people had been killed, more than 100 injured. It was our first taste of the incomprehensible gravity and danger of a place we’d entered by choice.

Stunned, we headed north, and before long we came to a very different street scene: lively blocks full of Internet cafés, CD stores, juice stands, and black-market money changers. We ducked into a café, fired off e-mails, and drank gallons of complimentary Iraqi tea amid the shop’s deafening Arab pop.

We’d given ourselves two weeks to find jobs. That afternoon, we set off for the

The center housed such noble operations as USAID, MCI, and Royal Jordanian Airlines. It also contained Coalition offices with names like Human Rights, Detainee Issues, and Alhurra, a U.S.-funded/Arab-anchored TV network.

Jeff and I split up; I headed for an office called NGO Assistance. When I walked in, I saw a dark-haired American woman in desert-camo fatigues talking to an office full of Iraqi women. She looked surprised to see me. I said hello, then asked, “Do you need any help? Like with work here?”

We swapped introductions. She was Army Sergeant Jody Lautenschlager, and her job was helping NGOs coordinate their activities in Iraq, which (I would later learn) involved a range of projects related to distributing material aid to the country’s citizens. “We actually do need some help,” she said, looking me over. “Do you have any experience in development and aid?”

“Sure,” I said, semi-lying. “I was just in Palestine, with the Red Crescent.” (While visiting the West Bank, Jeff and I spent a night hanging around with a Red Crescent ambulance crew.)

Jody said the two people who’d been heading up the NGO Capacity Building initiative were leaving. Then she said something about capacity building and civil societyto which I nodded, as if I understood any of what she was talking about.

“There is no doubt in my mind that I can handle the job,” I said. There was a lot of doubt. “My friend Jeff is here with me. He could fill the other position.”

“Great,” she said. “When can you guys start?” She grinned. “Oh, and we can’t pay you.”

“When can we start? Now. And about the money, that’s fine.”

We exchanged e-mail addresses, and that was that: Jeff and I were working for the Coalition.

NOT COUNTING ITS LOCATION, the Green Zone isn’t all that different from any big office park in America. There are the hotshots who have it wired, eternally lost souls, and lots of other people who seem smart enough but spend most of their time wondering how they ended up there.

Over time, we met an amazing cross section of soldiers, from terse Marine Corps officers to talky Civil Affairs reservists, from confident airborne troops to addled infantry recruits. The most impressive, by far, were the elite fighting forces like the 82nd Airborne company that guarded the convention center, fresh off a tour in Afghanistan. The least impressive was Sky’s unit, which was responsible for communications inside the Green Zone. Mostly, these soldiers staked out the chow line at the al-Rashid mess hall. Three times a day they ate like starving vultures.

Sky worked in a small boxchoked with radio equipmentthat was mounted on top of a Humvee and parked behind the convention center. “This place sucks,” he said as he gave us the grand tour one night. “People just call in and yell at me.”

We both felt awful for Sky. He’d just arrived in Iraq, so he wasn’t going anywhere soon. His boredom turned intoa desire for steroids, after he met a couple of Iraqi bodybuilders who worked in the convention center. “I need steroids,” he told us one night at dinner, in his typical blunt fashion. “Can you guys get some for me?”

We’d never bought steroids before, since we had little interest in shrinking our dicks and wrestling in front of a mirror. Finding a connection in Baghdad’s black market was easy, though, and Sky soon had his supply. As his muscles grew, he seemed to become a little prouder of being a soldier. Still, that didn’t stop him from regularly drinking on the job. One night, he was so “completely bombed” when he went on shift that he fell flat on his ass in front of a superior.

“He picked me up and threw me in the radio box and said, ‘You have to work,’ ” Sky complained. “I had to sit in there for 12 hours trying not to throw up.” Occasionally, Sky went off on tangents, talking about how many rounds per second his weapon could fire. When we pointed out that he sounded crazy, he agreed. “I was under psychological observation back in the U.S.,” he said. “I told the Army shrink at Fort Hood that I wanted to kill myself and other soldiers and that I didn’t want to go to Iraq.”

“Jesus,” Jeff said. “What did he say?”

“He said, ‘You’re going to Iraq, soldier.’ “

ONCE WE GOT JOBS, life in Baghdad settled into a basic routine. By day, we workedmoderating regular open-house meetings for Iraqis, international NGO employees, and military personnel; studying the database for Iraq’s reconstruction; and deciphering the blizzard of acronyms used by the military and CPA. Eventually we started making aid runs and writing up “field action reports” in the hope that, when the time came and Iraqis took over our jobs, they’d have an accurate paper trail to build on. By night, we ate, drank, and socialized with journalists, soldiers, and aid workers.

At $30 a night, the al-Rabei was too pricey for the long haul. So with help from a shady American we called Sketchy Dave, we found an apartment in a building in Karada, an OK neighborhood outside the Green Zone, on the east bank of the Tigris. The building was full of foreigners like us, the majority of them ultra-left militant peaceniks. We didn’t support the warfar from itand our basic take was that the invasion and occupation were grossly mismanaged clusterfucks. But Jeff and I were completely serious about working to make this bad situation a little better. As a result, we tended to find the lefties’ “No blood for oil!” rhetoric just as useless as anything the Bush administration said.

In our building, the most prominent lefty group was Circus 2 Iraq, whose members lived on the floor above us. Led by a young British law student named Jo Wilding, Circus 2 Iraq was composed of Europeans who’d come to Baghdad to make Iraqi kids laugh, a goal they never stopped mentioning.

“Wait, you guys are a circus?” Jeff asked Jo when we first met her, during an impromptu party in their apartment.

“Yeah, a circus. You guys work for the occupation?”

“Yeah,” I said. “We do NGO coordination for the CPA.”

“Why would you work for the CPA?”

“Because it’s our country,” I said.

“You support the war?”

“No.”

“Then how can you work for them?”

“Life is full of contradiction and compromise,” I said. “We’re just trying to help. The Coalition offered us work doing something we could do, so we’re doing it.”

“Nah,” Jo said. She wasn’t buying.

There were other clowns in the room, including Luis, a hash-loving Frenchman. Sensing a political debate brewing, he stepped in to make peace. “Politics are nothing,” he said. “Americans treat politics as an argument, like sport! Always yelling on TV. All politics is really negotiation.”

“So I want to negotiate,” Jo snapped.

“At least we’re doing something besides smoking pot and drinking moonshine,” Jeff said to Luis. “You ever see that movie Shakes the Clown? That’s you guys.”

“Who?” asked one of the clowns, a juggler named Peat.

“There’s a movie about this hard-living clown, starring Bobcat Goldthwait.” Pause. “Never mind.”

“Tell me.”

“Shakes is a scumbag clown, like Krusty.”

“Oh.”

Peat had been a war junkie for years. He said he’d lost a few teeth during an explosion in Northern Ireland, so now he wore dentures. That night he kept saying, “I luvvv chill-druun!” Then he’d take a long swig from a bottle of Jordanian booze, a brand that featured scantily clad girls on the labels. “I’m collecting all the ladies,” he said. “This is Cassandra. Would you like to meet her, boys?”

Truth be told, we drank plenty ourselves, but Jo didn’t. She hacked away busily on a laptop. Her serious, determined attitude slightly cramped the mood. But if not for her motivated spirit, Circus 2 Iraq would never have accomplished anything.

OBVIOUSLY, LIFE IN BAGHDAD wasn’t just clowns and booze. In early February, we left the Green Zone for our first day in the field, which involved distributing clothes collected by a charitable post office in Rhode Island. Jeff took off early for Karada. I went to Sadr Citya huge Shiite slum in the northeastern corner of Baghdadwith an Iraqi we called Mr. Mustachio, a forty-something man who didn’t speak English.

Mr. Mustachio had dark-brown slivers for eyes and an enormous tsunami of black, sculpted mustache. He’d started his own NGO to distribute aid to children in Sadr City. People I trusted vouched for him, so I decided to go along on one of his runs.

Early that morning, I walked through the al-Rashid Gate to his car, a small white station wagon with three of Mr. Mustachio’s friends huddled inside. We traversed Baghdad, and it took only a 40-minute drive to see that the city we worked inthe Green Zone bubble of palaces, restaurants, and fortificationswas not anything like what most Iraqis experienced. Sadr City was an utterly Third World hellhole that squeezed the population of Brooklyn, 2.5 million people, into eight square miles, an area about one-tenth the borough’s size.

As we drove into town, dust filled the air and donkeys munched piles of still-smoldering trash. Young men in stained athletic wear smoked cigarettes and stared at us. Women dressed head to foot in black abayas were orbited by swarms of children. Freelance Iraqi militiamen in black uniforms held Kalashnikovs, guarding mosque gates and patrolling the streets. Every roadside shop sold something dirty, old, or rotten.

There was no sign of the U.S. military or the official Iraqi police. There were a lot of posters of black-turbaned Shiite clerics. The gray-bearded face of Iraq’s most powerful man, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, was ever present. But the most popular poster depicted a white-bearded man, Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Sadiq al-Sadr, the populist cleric who’d been assassinated in 1999, allegedly on orders given by Saddam Hussein. Another featured Muhammad Sadiq’s son, the young, black-bearded Muqtada al-Sadr.

Around Sadr City, Muqtada was emerging as the Shiite version of Che Guevara. His defiant, iconoclastic attitude was striking a chord with the neighborhood’s surplus of young and disenfranchised Shiite men. Already, his meteoric rise was becoming one of the wild cards of the occupation, and it could be linked directly to the country’s demographics.

Iraq is a nation of some 25 million people, with a Shiite majority that was long oppressed by the Sunni Arabs who were in power under Saddam. As is true in many Arab and Third World countries, better than half the population is under 20, and Sadr City itself is jammed with young, poor, frustrated men. In the postwar power vacuum that was Iraq under the CPA, Muqtada filled the paternal role in Saddam’s collapsed state, and he began to cultivate a giant pool of discontented followers awaiting direction. He started speaking out against the Americans just after the fall of Saddam. In mosques, on the radio, in newspapers, he gave poor Iraqis a tangible enemy, answering the question of why life under the Americans wasn’t getting much better.

Of course, the U.S. didn’t intend to be an enemy of the Shiitesif anything, the occupation forces wanted to align with them as a way to offset the Sunnis. But the gulf between CPA intentions and Shiite reality was attractive to Muqtada, a man with a thirst for leadership, especially since that gulf was filled with hopeless people looking for a point to their lives.

MR. MUSTACHIO’S CAR stopped on the side of a bustling main street. A crowd of hundreds waited outside a building. In the sky, I saw minaretsit was a mosque, built into a crowded residential block. The engine stopped and I moved to open the door. Mr. Mustachio motioned for me to wait. The crowd ringed the car. A bullhorn sounded. I popped three Valiums and washed them down with water.

As the bullhorn quieted down, the crowd began to queue at the mosque’s doorstep. Those who didn’t line up, mostly young boys, felt the wrath of a belt or a shoe as two sheiks carved a path to the car to extract us. They kissed me on each cheek, shook my hands, and called me habibi”my friend.” Children grabbed at me. Whacka sandal to the head from a sheik. Undeterred, they kept clawing. Right about then I remembered who I was: a hungover Jew, high on drugs, standing outside a mosque in a dangerous part of Baghdad.

Mr. Mustachio and the sheiks started unloading aid boxes. We climbed a dark staircase packed with children. Old women, their faces and hands tattooed with henna, softly grabbed at me. The stairway led to a dark, musty room lit by a single naked bulb. Everybody was yelling. A sheik stepped up to act as my bodyguard. I dropped behind him.

The boxes were ripped open, and a line formed as free clothing was pulled out. A New England Patriots souvenir jersey was handed to a boy. A pair of shoes went to a little girl, a pair of tiny jeans to another. The crowd got excited; a twisting mosh pit formed. I saw a little girl crying as she was crushed against a wall. A sheik stood on a desk and shouted in Arabic. Calm resumed, and everyone started laughing. The first box was empty.

Then the lull ended and another scrum started. A baby girl, maybe two years old, was hoisted above the jostling people. Wearing a dirty pink jumper, she was screaming, and her red-faced tantrum made her the strangest of crowd surfers. Hennaed hands held the child up.

This went on for another 20 minutes, until all the boxes were empty. We walked out as we’d come in, with a sheik bouncer creating a trail to Mr. Mustachio’s car. By now it was around noon, the sun was cutting straight down through the dusty air, and the frenzied crowd was cheering and saluting. Mr. Mustachio looked to me for approval. I nodded and smiled, and we shook hands.

“Habibi,” he said. After that we beat it back to the Green Zone.

DURING FEBRUARY and into March, the CPA’s house of cards rose higher, only to eventually collapse from the weight of angry sectarian Iraqis, Coalition arrogance, and corruption that plagued all sides. By mid-March, Muqtada al-Sadr had started using his inflammatory newspaper, al-Hawza, to energize a huge slice of Iraqi men against the occupation, and the U.S.-led effort to stabilize Iraq had begun to skid.

We left the country in early April, when we were told by a reliable source that some Iraqis had target=ed us for assassination. (As it happened, we got out on the exact day Fallujah and Sadr City exploded into armed conflict against the Coalition.) During our months in Iraq, Marla Ruzicka, of CIVIC, became a friend of ours, and long after we were gone she continued to be a major force for good in a place where so much was bad. Tragically, Marla’s work came to an end in April 2005, when she was killed by a suicide bomber during a car trip near the Baghdad airport.

As for our pal Sky, things didn’t get any better. He kept doing steroids, kept hating the Army, and kept his eyes on the prize of going home to marry his fiancée. “I just want to kick back in my parents’ basement, smoke a bowl, put on a DVD, and space out,” Sky told us. “This is the worst decision I ever made. You know how some people are just not supposed to be in the Army?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Like me.”

“Well, that’s me a hundred percent, too, man. But it was too late once I realized it.”

This gave Jeff and me an idea. Another friend of ours, a stylish Brit named Inigo Gilmore, was shooting a documentary about life in occupied Baghdad. We decided he should film an interview with Sky, who was a perfect example of a hapless soldier trapped in a war he didn’t want to fight.

A few days later, the interview took place, with Sky providing an impassioned hourlong rant about how the Army had duped him and how his life was hell in half a dozen different ways. Cradling his M-16, Sky issued his cry for help on camera: I told many people I’ve been hearing voices in my head, trying to get them to take me seriously. But these people didn’t take me seriously, and here I am in Iraq…

Later, Jeff and I watched the footage and my stomach dropped. It was horrible, sad. I’d never really seen despair before. From the way Sky talked about killing himself, I could actually see him doing it. And he still had a year to go.