Rafael Mora and Fernanda Sandoval had spent the past three months hearing testimony related to the murder of their son, Jairo Mora Sandoval, an environmental activist who was killed while protecting endangered sea turtle eggs. Fernanda, 54, and Rafael, 62, were required to attend each day of the trial, making a three-hour trip from the family farm. Now, two years after the crime, a three-judge panel would deliver a verdict.

Delays had drawn out the trial, and a crowd packed the courtroom as the judges called the final session to order on January 26. Marched into the room with their hands shackled, each of the seven defendants looked haggard and anxious. They had been in preventative detention for more than a year since their July 2013 arrest.

Most observers thought they’d be convicted—cellphone transcripts, geolocation data, and eyewitness evidence all appeared to place them at the crime scene. So when the judges announced a verdict of not guilty, citing flaws in the prosecution’s case, Rafael Mora and Fernanda Sandoval were grief-stricken. They ran crying from the courtroom with arms wrapped around one another.

“It is the job of the investigators and the prosecution to properly manage a case to eliminate doubt, not create it,” said Judge Yolanda Alvarado.

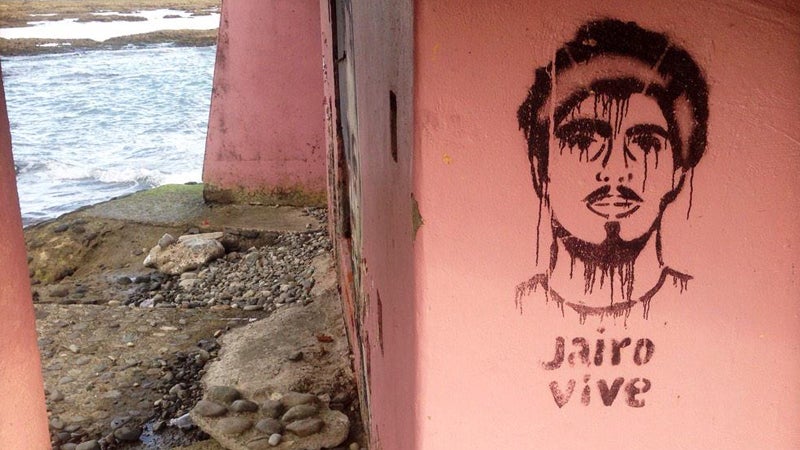

Down the road and near the shore, Mora’s 26-year-old face was stenciled in black paint on an abandoned building. Accompanied by the words “Jairo Vive” (“Jairo Lives”), this stamp has become a tribute to the environmentalist.

At the time of his murder, Mora worked for an NGO called , which focused on protecting the eggs of highly endangered leatherback sea turtles. Along with teams of volunteers—many of whom were American college students—he conducted patrols on Moín Beach, on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast. Located just outside Limón, the most dangerous city in Costa Rica, this 15-mile stretch of beach is a haven for drug activity. It’s also a leatherback nesting ground from February through July. The turtles provide an additional source of revenue for the beach’s criminal element. The poached eggs sell for about $1 on the black market.

Police presence was minimal on the beach, so Mora and his teams of volunteers provided the most effective protection for the turtles. They’d try to grab newly laid eggs, then move them to a hatchery. On the night of May 30, 2013, Mora left the wildlife sanctuary to patrol for turtles and never returned. His naked and beaten body was found facedown the next morning on Moín Beach. An autopsy revealed that he had been dragged behind a car through the sand until he died of asphyxiation.

Mora’s death shocked Costa Rica, a country known worldwide for its pristine green image. There were protests in the capital, and environmental groups vowed to protect the turtles of Moín in Mora’s stead.

When seven men were arrested for the murder on July 31, 2013, environmentalists were hopeful. The suspects were Héctor Cash, Enrique Centeno, William Delgado, José Bryan Quesada, brothers Darwin and Donald Salmón, and the group’s ringleader, Felipe Arauz. The men allegedly comprised a well-known poaching gang. According to Vanessa Lizano, owner of the Costa Rica Wildlife Sanctuary and one of Mora’s close friends, the men had brought an unpredictable and violent element to the beach.

“Up until the last few years, we really had a friendly relationship with most of the poachers,” Lizano said. “Those guys were the only group that ever gave us any trouble.”

Another poacher, Róger Salguera, corroborated Lizano’s theory. He claimed to have seen Arauz in Moín on the night of Mora’s murder. During the trial, Salguera testified that he passed by Arauz’s car parked on the beach sometime after midnight. He spotted tire tracks and something in the sand up ahead but was chased off by a masked man before he could tell what—or who—it was.

Other evidence also seemed to link the accused to the crime. Investigators were able to place each of the suspects’ cellphones on Moín Beach at the time of the murder through geolocation. The Judicial Investigation Police (OIJ), Costa Rica’s version of the FBI, obtained hours of recorded telephone conversations in which the defendants allegedly discussed killing Mora. The OIJ’s case file contains transcripts of text messages from Darwin Salmón to Quesada that appeared to make the prosecution’s case: “We dragged him behind Felipe’s car and you know it.”

[quote]The [investigators’] case file contains transcripts of text messages from Darwin Salmón to Quesada that appeared to make the prosecution’s case: “We dragged him behind Felipe’s car and you know it.”[/quote]

But at the trial, nearly all of this evidence was either lost or excluded. A preliminary court judge misplaced a disk containing telephone conversations. Another set of phone conversations was excluded when the prosecution failed to properly preserve the privacy of the accused by not filtering out discussions unrelated to the case. Two vials of cologne that had been used to identify Donald Salmón mysteriously disappeared from the evidence room. And the prosecution failed to log the telephone conversations into evidence at the beginning of the trial. Ultimately, judges ruled the OIJ’s telephone investigation inadmissible. As a result, the detectives were unable to prove that the defendants were on the beach on morning of May 31, 2013.

With almost no evidence remaining to link the defendants to the murder, the three-judge panel acquitted all seven suspects, though Cash, Centeno, Quesada, and Donald Salmón will still go to prison for a separate rape and robbery conviction that was made during Mora’s trial. In her closing verdict explanation, Judge Yolanda Alvarado delivered a critique to the prosecution and investigators.

“Unfortunately, the management of evidence broke the chain of proof in this case,” Alvarado nearly shouted into the courtroom.

The verdict has reopened the wound of Mora’s murder within Costa Rica’s environmental community. There is no double jeopardy in Costa Rica—defendants can be tried up to three times—and Mora’s family’s lawyer has promised to file an appeal.

On Thursday, hundreds of protesters gathered in the capital, and environmental groups are again calling for action on Moín Beach. But the outrage has meant little at the scene of the crime. Nobody has stepped up to take Mora’s place.

“My parents have been fighting to try to stay, but I don’t think this is a fight we are going to be able to continue,” Lizano said. “When you get beat up too many times, you start to give up. I don’t believe in this government. There’s no justice here.”