The California Lake Killing Everything Around It

What's that smell? It's a teeming avian sanctuary—and a sump of troubled waters. It's a mess that we created—and a puzzle we can't solve. It's California's Salton Sea, a hypersaline lake that kills the very life it shelters.

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up! .

The water's edge at the south end of North Shore—a shuttered, graffiti'd, ruined resort town which, as you might have guessed, lies near the north shore of California's Salton Sea—was no different than usual, the beach comprising not sand but barnacle shells, fish bones, fish scales, fish corpses, and bird corpses, its accompaniment an almost unbearable ammoniac stench like rancid urine magnified. Fish carcasses in rows and rows, more sickening stenches, the underfoot crunch of white cheek-plates like seashells—oh, rows and banks of whiteness, banks of vertebrae; feathers and vertebrae twitching in the water almost within reach of the occasional half-mummified bird. Meanwhile, the dock was crowded with live birds—long-necked white pelicans. Their coexistence with the dead birds was jarring, but then so was the broken concrete, the private property sign, the half-sunk playground slide.

It had been worse in other years—seven and a half million tilapia (African perch) died on a single August day in 1998—but this evening it happened to be better. Oh, death was there, but matter had been ground down to submatter, just as on other beaches coarse sand is gradually ground fine. The same dead scales, the barnacles licked at by waves of a raw sienna color richly evil in its algal depths, set the tone, let's say: crunch, crunch. Without great difficulty I spied the black mouth of a dead fish, another black mouth, barnacles, a dead bird, and then, of all things, another black mouth.

The far shore remained as beautiful as ever. When each shore is a far shore, then the pseudo-Mediterranean look of the west side as seen from the east side (rugged blue mountains, birds in flight, a few boats) shimmers into full believability. Come closer, and a metallic taste alights upon your stinging lips. Stay awhile, and you might win a sore throat, an aching compression of the chest as if from smog, or honest nausea. I was feeling queasy, but over the charnel a cool breeze played, and a family approached the water's edge, the children running happily, sinking ankle-deep in scales and barnacles, nobody expressing any botheration about the stench or the relics underfoot. Could it be that everything in this world remains so fundamentally pure that nothing can ever be more than half-ruined? Expressed in the shimmer on the Salton Sea—sometimes dark blue, sometimes infinitely white, and always pitted with desert light—this purity is particularly undeniable.

Honeymoon paradise and toxic sump. Teeming fishery stinking of dead fish, bird sanctuary where birds die by the thousands. (What choice do the birds have? are gone!) Lovely ugliness—this is the Salton Sea.

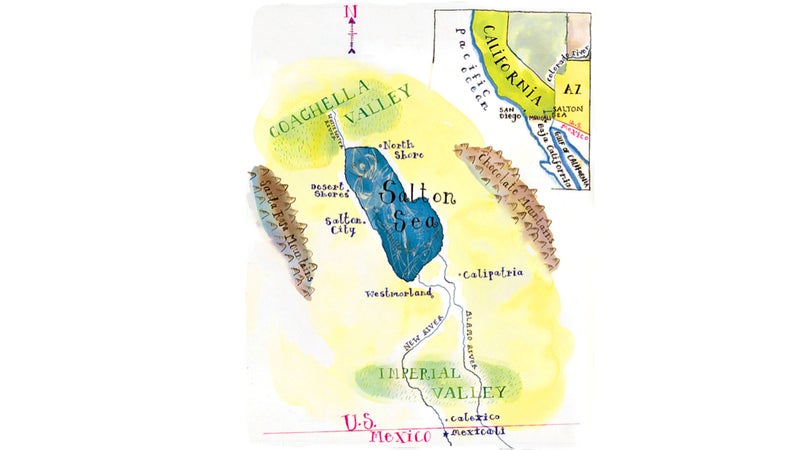

If you are confused, so is everybody else. in 1905–1907, when an attempt to divert the Colorado River (and, incidentally, to steal a lot more of Mexico's water) sent a series of floods into the salt-caked basin of California's Imperial Valley, the new sea kept rising, for like all seas it has no outlet. Farms, saltworks, and pieces of towns went under, and by the time the leak was plugged in 1907, the sea covered 500 square miles. Experts predicted evaporation within 20 years. And the water level did go down, at first. But a century later, it still takes up 380 square miles.

In the beginning it was a freshwater realm; trout survived here as late as 1929; a National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1930. Tourists came right away, but the golden age of fishing and waterfowl hunting that old-timers remember started to fade in the 1960s, when the sea began to stink a trifle and the resorts began to board up their windows. Ecologists were already warning that if the salinity—fed by irrigation runoff from the Colorado Desert's salt-rich soils, souvenir of a prehistoric ocean—continued to increase, the sea would become a wasteland. It did rise, of course, and the sea itself crept higher, too; Salton City and Bombay Beach lost houses beneath these strange reddish-brown waters.

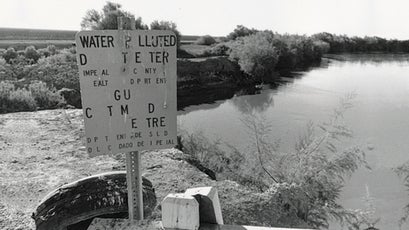

Where were those waters coming from? From the Alamo River, 52 miles of irrigation runoff in whose bamboo rushes Border Patrol agents now play out their pretend-Vietnam cat-and-mouse exercises; from the rather irrelevant Whitewater River, trickling in from the northwest; and from the New River, with its reputation for filth, gathering sewage, landfill leachate, and industrial waste in the Mexican boomtown of Mexicali before turning north to receive fertilizers and pesticides from Imperial Valley fields, meanwhile picking up a little more salt and a little more salt.

The great die-offs began in the 1990s—150,000 eared grebes in 1992, 15,000 pelicans in 1996, fish by the millions, tilapia and croaker and corvina that had been stocked back in the fifties. Environmentalists raised alarms about the dead birds, the algal blooms, the hypersalinity, and the selenium, a naturally occurring trace element that in high concentrations can be deadly to plants and animals. They studied the sea, but none came to the same conclusions, or they came to no conclusions at all. The only thing everyone agreed on was that the sea was now 25 percent saltier than the ocean itself, and that it would only get saltier until the birds and fishes still surviving there were gone.

They say that as California goes, so goes the nation. And to me the Salton Sea emblematizes California. What can we do about it? What should we do? What does it “mean”? I decided to undertake a course of aquatic exploration. I would ride the New River from its source in Mexico to the Salton Sea, which I'd never heard of anybody doing. How navigable the river was, how dangerous or disgusting, not a soul could tell. My acquaintances in Imperial County said that yes, it did sound like a stupid thing to do, but probably not that unsafe; the worst that would likely happen to me was sickness. The U.S. Border Patrol advised against it, incidentally promising me that should I cross into the United States by means of the New River, I'd infallibly get arrested.

North of the border, the New River curves and jitters for 60 miles in a backward S to a sort of estuary on the southern shore of the Salton Sea, equidistant from the towns of Calipatria and Westmorland. On a map of Imperial County, the towns and road-crossings of its progress are traced in blue, right down to the last demisemiquaver. But immediately south of Calexico's stubby fan palms and pawn shops, there runs a heavy line demarcating the end of California and the beginning of Mexico, and of the state of Baja California. Here the New River becomes the Río Nuevo, and vanishes upstream from all but one of the maps I've ever seen, each time in a different way.

My plan was to cross from Calexico into Mexicali, hire a taxi, and get the driver to take me to the source of the Río Nuevo—wherever that was, but according to most accounts, just a few miles outside of town. Then I would rent a boat and ride downstream. But once I arrived in Mexicali and sought to zero in on the mysterious spot (excuse me, señor, but where exactly does it start?), people began to tell me that the river commenced right here, in Mexicali itself, in one of the city's industrial parks, where a certain Xochimilco Lagoon was fed by a secret spring. Moreover, the municipal authorities of Mexicali were even now pressing on into the fifth year of a very fine project to entomb and forget the Río Nuevo, sealing it off underground along a concrete channel below the median strip of a new highway, whose name happened to be Boulevard Río Nuevo—a hot white double ribbon of street adorned with dirt and tires, an upended car, broken things. Along its median they'd sunk segments of a long, long concrete tube that lay inconspicuous in a dirt trench; and between some of these segments, where the tube had been buried, were grates. Lifting the grates revealed square pits, with jet-black water flowing below, exuding a fierce sewer stench that could almost be some kind of cheese.

Not far from the border, a yellow pump truck sat roaring as its hose, dangling down into the Río Nuevo, sucked up a measure of the effluvium of Mexicali's 750,000 people. This liquid, called by the locals aguas negras, would be used in concrete mixing. What treasures might the river gather here on its way to the United States? Bacteria that could lead to typhoid, hepatitis, amoebic dysentery, perhaps a few other things, says the Environmental Protection Agency. (Well, the kids have respiratory problems just from living here, said one señora who lived a few steps away. They have coughs, she said, and on the skin some pimples and rashes.) Beside the truck were two wise shade-loungers—the temperature was 114 degrees—in white-dusted boots, baseball caps, and sunglasses. I asked what was the most interesting thing they could tell me about the Río Nuevo. They conferred for a while, and finally one of them said that they'd seen a dead body in it last Saturday.

One of the men, José Rigoberto Cruz Córdoba, was a supervisor. He explained that the purpose of this concrete shield was to end the old practice of spewing untreated factory and municipal sewage into the river, and maybe he even believed this; maybe it was even true. My translator, a man who, like most Mexicans, does not pulse with idealism about civic life, interpreted the policy thus: They'll just go to the big polluters—American companies or else Mexican millionaires—and say, “We've closed off your pipe. You can either pay us and we'll make you another opening right now, or else you're going to have to do it yourself with jackhammers and risk a much higher fine.” No doubt he was right, and the clandestine pipes would soon be better hidden than ever.

The generator ran and the Río Nuevo stank. The yellow truck was now almost full. Smiling pleasantly, Señor Cruz Córdoba remarked, “I heard that people used to fish and swim and bathe here 30 years ago.”

That night, at a taxi stand in sight of the river, the cab drivers sat at picnic tables, and the old-timers told me how it had been 25 years ago. They'd always called it the Río Conca, which was short for the Río con Cagada, the River with Shit. The river was lower then, and they used to play soccer here; when they saw turds floating by, they just laughed and jumped over them. The turds had floated like tortugas, they said, like turtles; and indeed they used to see real turtles here. Now they saw no animals at all.

For three or four languid days, I sat in the offices of Mexican civil engineers, telephone-queried American irrigation-district officials, and then, in the company of various guides and taxi drivers, went searching for the source of the Río Nuevo. Sometimes the street was fenced off for construction, and sometimes the river ran mysteriously underground—disappearing, say, beneath a wilderness of pemex gas stations—but we always found it again, smelling it before we could see it. At Xochimilco Lagoon, liquid was flowing out of pipes and foaming into the lagoon's sickly stinking greenness between tamarisk trees.

But the lagoon was not the source, because there was no single source; the Río Nuevo drew its life from a spiderweb of irrigation drains and sewers and springs and lagoons, most of which ultimately derived from the Colorado River. Easing my way past the sentry at a geothermal works, I discovered waters of a lurid neon blue; what had stained them? That water entered the Río Nuevo, and so did this channel and that channel and that channel drawn on the blueprints of the engineers. From a practical point of view, the end came when I peered into the stinking greenness of Xochimilco Lagoon and the taxi driver appropriately said, “The end.”

I'd already realized that my plan to raft the Río Nuevo was shot. Early one evening, the heat stinging my nose and forehead deliciously, I had gone to the river, peered down one of the square pits, and wondered whether I would stand a chance if I lowered myself and a raft into it. The current appeared to be extremely strong; there was no predicting where I'd end up. At best I'd drift as far as the border, five miles away, and be arrested. Should there be any underground barrier along the way, my raft would smash into it, and I'd probably capsize and eventually starve, choke, or drown.

While I considered the matter, my latest taxi driver stood on a mound of dirt and recited “El Ruego,” by the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral. Thus Mexico, where the most obscene feculence cannot prevail over art. It was settled. Since I couldn't spend my own death benefits, I decided to begin my little cruise in the USA.

How many Río Nuevos, how many Salton Seas on this planet already lay poisoned—if they were poisoned—for the long term? The Aral Sea? Love Canal? Lake Baikal? Would their new normality become normative for the rest of us? How bad off is the Salton Sea, really?

“Stories of a polluted Salton Sea are greatly exaggerated,” a recent brochure from the Coachella Valley Historical Society informed me. In 1994 the author of the pamphlet, “Salton Sea: California's Overlooked Treasure,” had taken a drive around the sea with her husband and experienced “a wonderful sense of what is right with the world.” Five years later, the authors of an alarming and beautifully photographed volume titled described that same idyllic sea as “a stinking, reddish-brown sump rapidly growing too rancid for even the hardiest ocean fish” and “a death trap for birds.” The New River, in particular, “claims the distinction of being the filthiest stream in the nation,” the authors wrote. And as Fred Cagle, head of the California Audubon Society's Salton Sea Task Force, told me: “Nine million pounds of pesticides a year on Imperial Valley fields have got to go somewhere!”

I decided to ride the New River from its source in Mexico to the Salton Sea. The Border Patrol advised that if I tried crossing into the U.S. that way, I'd infallibly get arrested.

There you have it, but according to that confederation of counties and water districts called the what you have is no more than “Myth #5: The Sea is a Toxic Dump Created by Agriculture.” According to the SSA leaflet “Myths and Realities,” “Pesticides are not found at any significant level in the Sea.” Moreover, selenium levels are only one-fifth of the federal standard, and (if I may quote from the rebuttal to Myth #4), “Water carried by the New River from Mexico is not a major contributor to the Sea's problems.” Still, the leaflet freely if euphemistically confesses the “bird disease outbreaks,” “fluctuating surface levels” (which I take to be a tacit reference to the half-buried houses, or to the mostly submerged Torres-Martinez Indian Reservation on the northwest shore), and “nutrient-rich water, algal blooms, and fish kills” (symptoms of what ecologists call eutrophication, which occurs when too much sewage or detergent or fertilizer enters a body of warm water and algae rushes in to exploit, growing like crazy, sucking up all the oxygen, and suffocating the fish). The leaflet acknowledges only one cause for these problems, the one everybody agrees on: salinity. Needless to say, salinity cannot explain algal blooms. As the leaflet reminds us, “We do not know all there is to know about the Sea.” There again you have it.

Not that we haven't tried: Is there an agency in the area—international, federal, state, tribal, or local—that has not dipped its sample vials in the waters of the Salton Sea and the New River, looking to discover its secrets? U.S. Fish & Wildlife, the Imperial Irrigation District, the Twentynine Palms Band of Luiseno Mission Indians, the Regional Water Quality Board, the University of California-Davis—all of them and more have monitored selenium levels and nutrient levels and oxygen levels, testing for this and for that. Did their data overlap? No one knows, there was no clearinghouse, they didn't have the funding, that person no longer works here. But in 1998, Congress passed the Salton Sea Reclamation Act, which provided for the Salton Sea Restoration Project, which will conduct more studies. That same year the University of Redlands created the Salton Sea Database Program, whose aim is to collate that lost information and map the environment of the sea. Then will we know?

As for the pelicans, the grebes, and the other birds, they continue their tragic dramas. Whether they get sick from eating the dead fish or from something else entirely nobody knows, but they keep dying—from avian cholera, botulism, and Newcastle's disease. No matter that scientists haven't pinpointed the cause: If you walk the crunching beaches of North Shore, you cannot help but have a feeling that something about the Salton Sea is causing these die-offs, with their increasing if unpredictable frequency.

“We seem to have far too many of these,” admits Tom Kirk, the executive director of the Salton Sea Authority. “But keep this in mind, Bill. Twenty thousand birds died at the Salton Sea last year. That's less than 1 percent of the bird population.”

José Lopez, and ex-marine with a cheerful, steady, slightly impersonal can-do attitude, clerked at the motel where I was staying in Calexico. When I told him that nobody seemed willing to take me on the New River or even to rent me a rowboat, he proposed that I go to one of those warehouse-style chain stores which now infested the United States and buy myself an inflatable dinghy. I asked if he would keep me company, and he scarcely hesitated. “Anyway,” he said, “it will be something to tell our grandchildren.”

The store sold two-person, three-person, and four-person rafts. I got the four-person variety for maximum buoyancy, selected two medium-priced wooden oars, paid $70, and felt good about the bargain. I'd prevailed upon José to bring his father over the border from Mexicali; the old man would drive José's pickup truck and wait for us at each crossing of the road, always going ahead rather than behind, so that if we had to walk in the heat we'd be sure of which direction to go. If we waved one arm at him, he'd know to drive to the next bridge. Two arms would mean we were in trouble.

I worried about two possibilities. The first and most likely but least immediately serious was that we might get poisoned by the New River. The second peril, which seriously concerned me, was dehydration. Should we be forced to abandon the boat in some unlucky spot between widely spaced bridges, it wouldn't take long for the heat to wear us down. It was supposed to be not much over 110 degrees, so it could have been worse.

José was behind his desk at the motel on the eve of our departure, laboriously inflating the dinghy breath by breath whenever the customers gave him a chance. This was the kind of fellow he was: determined, optimistic, ready to do his best with almost nothing.

At seven the next morning, with Imperial County already laying its hot hands on my thighs, the three of us—José, his father, and I—huddled in the parking lot of a supermarket, squinting beneath our caps while José's father stick-sketched in the dirt, making a map of the New River with the various road-crossings that he knew of. We were just north of the spot where the river comes through a gap in a wall that marks the border; across the highway, a white Border Patrol vehicle hunched in the white sand, watching us.

The first place that the old man would be able to wait for us was the bridge at Highway 98, about a mile due north but four miles' worth of river, thanks to a bend to the west-northwest. The next spot he could guarantee was Interstate 8, which looked to be a good ten miles from Highway 98, if one factored in river bends and wriggles.

Sheep-shaped clots of foam, white and wooly, floated down the river. Still, all in all the water didn't smell nearly as foul as in Mexicali. We dragged the dinghy out of the back of the truck, and José, who from somewhere had been able to borrow a tiny battery-powered pump, tautened his previous night's breath work until every last wrinkle disappeared. From the weeds came another old man, evidently a pollero—a coyote, or smuggler of illegal immigrants—who laughed at the notion that José and I were going to be literally up Shit Creek.

We dragged our yellow craft down a steep path between briars, and then the stench of the foaming green water was in our nostrils as we stood for one last glum instant on the mucky bank. I slid the dinghy into the river. A fierce current snapped the bow downriver, and I held the boat parallel to the bank as José clambered in. Then, while José's father gripped it by the side rope, I slid myself over the stern and felt José's trapped breath jelly-quivering flaccidly beneath me. I had a bad feeling. The old man pushed us off, and we instantly rushed away, fending off snags as best we could. There was no time to glance back.

Shaded on either side by mesquite trees, paloverdes, tamarisks, bamboo, and grass, the deep-green river sped us down its canyon, whose banks were stratified with what appeared to be crusted salt. An occasional tire or scrap of clothing, a tin can or plastic cup wedged between branches, and once what I took to be the corpse of some small animal, then became a fetus, and finally resolved into a lost doll floating face down between black-smeared roots—these objects were our companions and guideposts as we whirled toward the Salton Sea, spinning in circles because José had never paddled before in his life.

Every now and then I'd see us veering into the clutches of a bamboo thicket or some slimy slobbery tree branches, and I'd drop my notebook or camera and snatch up my oar, which was now caked with black matter (shall we be upbeat and call it mud?). Then woody fingers would seize us, raking muck and water across our shoulders as we poled ourselves away. The first drops on my skin seemed to burn a little bit, but no doubt I was imagining things.

José kept spraying me by accident. There was not much to do about that; certainly I couldn't imagine a gamer or more resolute companion. He was definitely getting tired now, so I laid down my notebook between my sodden ankles and began to paddle in earnest. We were passing a secluded lagoon into which a fat pipe drained what appeared to be clear water. We sped around a bend, and for no reason I could fathom the stench got much worse—whiffs of sewage and carrion, as in Mexicali. I vaguely considered vomiting, but by then we were riding a deeper stretch that merely smelled like marsh again. The water's green hue gradually became brown, and the white foam, which occasionally imitated the faux-marble plastic tabletops in some Mexicali Chinese restaurant, diluted itself into bubbles. Everything became very pretty again with the high bamboos around us, their reflections blocky and murky on the poisoned water. Occasionally we'd glimpse low warehouses off to the side.

Another inlet, another pipe (this one gushing brown liquid), and then we saw a duck swimming quite contentedly. Black-and-white birds, possibly phoebes, shrieked at us from the trees. I got a beautiful view of garbage snagged under dead branches.

The heat was getting miserable, and my end of the boat, having punched into one bamboo thicket too many, hissed sadly under me, sinking slowly. Since the boat featured several airtight compartments, I wasn't too worried, but I didn't really like it, either. Meanwhile the river had settled deeper into its canyon, and all we could see on either side were bamboos and saltcedars high above the bone-dry striated banks. A wild, lonely, beautiful feeling took possession of me. Not only had the New River become so unfrequented over the last few decades that it felt unexplored, but the isolating power of the tree-walls, the knowledge that the adventure might in fact be a little dangerous, and the surprisingly dramatic loveliness of the scenery all made me feel as if José and I were explorers of pre-American California. But it was so weird to experience this sensation here, where a half-mummified duck was hanging a foot above water in a dead tree! What had slain it?

At midmorning the river, now a rich neon lime, split into three channels, all of them impassable due to tires and garbage. Above us, José's father waited at the Highway 98 bridge. I called it quits.

Even after taking a shower my hands kept burning, and the next day José and I still couldn't get the taste out of our mouths. We used up all his breath mints lickety-split; then I went to Mexicali for tequila and spicy tacos. The taste dug itself deeper.

Poor José only got $100. I had to give Ray Garnett, formerly the proprietor of Ray's Salton Sea Guide Service, $500 before he'd consent to take me down the last ten-mile stretch of the New River. Ray had been a fishing guide for decades. Now that he was retired, he still went out on the Sea pretty often, to keep even. He called the Salton Sea the most productive fishery in the world.

“How about the fish, Ray?” I asked.

“I've been eatin' 'em since 1955, and I'm still here, so there's nothin' wrong with 'em,” he replied.

As a matter of fact, he thought the Salton Sea must have improved, because he used to get stinging rashes on his fingers when he cleaned too many fish, and that didn't happen anymore.

About the New River, Ray had very little information. He'd never been on it in all his 78 years, and neither had anybody else he knew. That was why he was willing to hazard his $800 aluminum water-skimmer with its $1,200 outboard motor on a cruise. He was even a little excited. He kept saying, “This sure is different.”

Ray preferred corvina to tilapia, and he brought some home-smoked corvina along in the cooler. Probably I was imagining the aftertaste.

Stocky, red, hairy-handed, round-faced, Ray did everything slowly and right, his old eyes seeing and sometimes not telling. We put the boat in near Westmorland, and the river curved us around the contours of a cantaloupe field, with whitish spheres in the bright greenness, then the brown of a fallow field, a dirt road, and at last the cocoa-brown of the river itself, whirling us away.

The New River's stench was far milder here, the color less alarming; and I remembered how, when I'd asked Tom Kirk of the Salton Sea Authority how much of the Salton Sea's sickness came from the New River, he'd promptly answered, “People point their fingers at Mexico and at farmers. The perception that the Salton Sea is Mexico's toilet is unfair.”

Maybe he was right, God knows. Maybe something else was causing the fish deaths and the bird deaths.

“You think there are any fish in this river, Ray?” I asked.

“Flathead catfish. I wouldn't eat 'em. One time we did core samples of the mud in these wetlands. It has just about everything in it.”

“Like what?” I asked, but Ray stayed silent.

A little later, he said, “Must be something wrong with this water, 'cause I don't see any bullfrogs. I been watchin' the bank. No turtles, either. Bullfrogs and turtles can live in anything.”

Swallows flew down. The river was pleasant, really, wide and coffee-colored, with olive-bleached tamarisk trees on either of its salt-banded banks. We can poison nature and go on poisoning it; something precious always remains. There is always something that our earth has left to give, and we keep right on taking.

Lowering our heads, we passed under a fresh-painted girder bridge that framed a big pipe. There was a sudden faint whiff of sewage, but the river didn't stink a tenth as much as it had at the border, let alone in Mexico. Passing a long straight feeder canal with hardly any trash in it, we found ourselves running between tall green grass and flittering birds. To the northwest, Villager Peak in the Santa Rosa Mountains was a lovely blue ahead of us.

“Have another piece of that corvina,” Ray said.

The river was pleasant, really, wide and coffee-colored. We can poison nature and go on poisoning it; something precious always remains.

Now there were just hills of bamboo and grass on either side, like the Everglades. Four black-winged pelicans flew together over the grass. The sunken chocolate windings of the New River seemed to get richer and richer. But another smell began to thicken. “The sea's right on the side of these weeds here,” Ray was saying.

“What's that smell, Ray?”

“I think it's all the dying fish, and dead fish on the bottom. It forms some kind of a gas. It's just another die-off. It's natural.” Was it? Ducks were flitting happily, and we saw dozens of pelicans as we came out into the sea.

“You get away from the smell when you get out here fishin',” Ray said, and he was right. Out on the greenish-brownish waves—”That's algae bloom that made the water turn green. Won't be any fish in here today”—the only odor was ocean.

“They've had studies and what have you ever since the late fifties,” Ray sighed. “In 1995 we put 420 hours in and didn't catch a fish. But in '97 and '98 they started coming back. Whether the fish have gotten more tolerant or whether it's something else, I don't know.”

Deep in an orangish-green wave, Ray thought it best to turn around. As we approached the river we grounded on a sandbar.

“If you don't mind getting your feet wet,” Ray said, “it sure would make things easier.”

We pushed. From the shore came a sickening sweet stench of rotting animals, and I soon had a sore throat and my eyes began to sting. When I left him, Ray gave me a kind and gentle smile, and an entire bag of smoked corvina.

“No face which we can give to a matter will stead us so well at last as the truth.” That is what Thoreau wrote when he was measuring and meditating upon Walden Pond. “For the most part,” he continued, “we are not where we are, but in a false position. Through an infirmity of our natures, we suppose a case, and put ourselves into it, and hence are in two cases at the same time, and it is doubly difficult to get out.”

Throughout my researches into the New River and the Salton Sea, I found myself similarly in two cases at the same time. My fault lay in this: I had drunk in a certain doctrine, whose sources are as obscurely ubiquitous and whose substance is as tainted as New River water: that only an “expert” has the right to judge the acceptability of the water of life. The only way I could think of to decide the matter was to abrogate my own judgment and pay technicians to analyze a water sample from the river, and another from the sea. And then I'd know, because a printed report would tell me. But I already knew the truth. The Salton Sea is ghastly. The New River is ghastly.

Squatting over the stinking green water a few steps from the spot where José and I had launched our dinghy, I lowered sterile sample bottles one by one in my latex-gloved hands, standing partly on a fresh human turd to avoid falling in. The chemical odor seemed more dizzying than usual. What was it? I was hoping to find out. I was angling for your basic herbicide-pesticide sweep, including the chlorinateds (EPA method 8151); a CAM-17 for heavy metals; a full method 8260, needless to say, with MTBE and oxygenates; a TPH (that's total petroleum hydrocarbons to you); a surfactant; and a diesel test while I was at it. Originally I'd craved a fecal coliform count so badly I could taste it, but Tom Kirk had told me that the levels of fecal coliform, high at the border, dipped and then rose again at the mouth of the Sea, thanks to all the birds. So to hell with it.

I took my Salton Sea sample up in North Shore. It seemed like a good place because it was far enough away from the New River to reflect the base level of filthiness, so to speak, and it was also good on account of all those fish bones and salt-stiffened feathers. There was only one dead bird on the beach this time, a fluffy little baby. On the pier a man was fishing, perhaps not impressed by the selenium health advisory strongly suggesting that no one eat more than four ounces of Salton Sea fish-meat per two weeks.

I got my two water samples analyzed at California Laboratory Services in Sacramento. Sample one was the New River. Sample two was the Salton Sea.

“On the chlorinated acid herbicides, your 2, 4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid took a hit on sample one,” said the lab man. “On sample two, everything was non-detect. Let's see now, your diesel in the very first sample took a very small hit; the second sample was non-detect. For metals your first sample showed beryllium and zinc, and your second had barium and selenium. Both samples were well below the maximum legal contaminant levels on all that. We ran the 8260 for volatiles plus oxygenates. Both samples were clean.”

I inquired how my samples compared to other water they'd tested.

“Relatively clean compared to other wastewater samples,” the lab man said. “They're certainly not nearly as nasty as some of our samples from Brazil, Singapore, and China.”

I called up the Audubon Society man, Fred Cagle, who'd always struck me as extremely levelheaded and independent. “Do these results surprise you?” I asked him.

“Not at all.”

“Well, is the New River the most polluted body of water in North America, or one of the most polluted, or what?”

“It's been getting cleaner,” he said. “But it still gets that reputation. It depends on who you talk to. They've found cholera, TB, all that kind of crap.”

“What about the metals and organics, from pesticides?”

“It varies tremendously. We've taken hundreds of samples, and they all come out different. The stuff in the sediments may not be soluble; there are just so many variables. Of course you can't figure it out. Scientists can't figure it out.”

“And those nine million pounds of agricultural chemicals you mentioned, where do they go?”

“Some of them break down, some of them get oxidized by bacteria. But we don't know that. Scientists get confused too.”

“Would you agree that the Salton Sea is the most productive fishery in the world?”

“It's the most productive fishery, but it's also the most limited fishery. All the fish are artificial. We're getting right close to the edge of the salinity window. And why spend $100 million to save a $10 million fishery? Tilapia are an amazing fish. You know, they're a freshwater fish, and in 30 generations they've modified themselves to live in the Salton Sea. But has anybody told you about the parasite levels on those fish? They're enormous. Parasites are in their lungs, everywhere. The people who eat those fish might not enjoy them as much if they knew that.”

“I still have a little smoked corvina left,” I said. “Maybe I won't send it to you.”

“Good idea.”

From the mouth of the New River, on the southern edge of the Salton Sea, it's a straight shot halfway up the sea's west coast to Salton City, followed by Salton Sea Beach, then the nearly defunct Sun Dial Beach, and finally Desert Shores, where beside the rickety dock stinking white fishes gaped in the sun, swirling with each algal wave. A couple backed their boat down the boat ramp, the man steering, the woman craning her head with extreme seriousness. Fish corpses squished beneath their wheels. Meanwhile, Salton City's attractions included a broken motel with drawn-in palm fronds and shattered windows. Emblems of stereotypical cacti and flying fish clung to the motel just as a fool clings to his dying love; its customers were heat, rubble, and cicada song.

The article on California in the 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, published in 1911, states that irrigation along the Colorado River, which naturally bears only desert vegetation, has made it a true humid-tropical region, growing true tropical fruits. Wasn't that the golden age? Actually, the golden age hasn't ended even now. Looking around me at the Salton Sea's green margins of fields and palm orchards, I spied a lone palm tree far away at the convergence of tan furrows, then lavender mountains glazed with confectioner's sugar; this is the landscape where all is beauty, the aloof desert mountains enriched despite themselves by the spectacle of the fields.

Fertilization, irrigation, runoff, wastewater—the final admixtures of all these quantities flow into the Salton Sea. I couldn't condemn the state of the Sea without rejecting the ring of emerald around it. About the continuing degradation of that sump, José Angel of the Regional Water Quality Board very reasonably said, “It's a natural process because the sea is a closed basin. Pollutants cannot be flushed out. You could be discharging Colorado River water directly into the Salton Sea, or for that matter distilled water into the Salton Sea, and you would end up with a salinity problem, because the ground is full of salt! The regulations do not provide for a solution to this. You have to build some sort of an outlet.”

Will they? Are they? The Salton Sea Restoration Project, that congressional marriage of the Salton Sea Authority and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, attended by a wedding party of some dozen other agencies, is following the favored bureaucratic course of studying the problem some more, and maybe some of its proposed alternatives will even do something: evaporation ponds, fish harvesting, carcass-skimming barges, wetlands habitats, displacement dikes, diverted Colorado River inflows, desalination ponds. But what about the salt and chemicals rolling in from the fields? “What can you do?” Angel had asked me. “Because fertilizers have a legitimate agricultural use.”

I could see that legitimate agricultural use, reflected in the stylized elegance of a palm grove's paragraph of tightly spaced green asterisks and in the ridge-striped fields south of Niland, where sheep and birds intermingled, the cotton balls on their khaki-colored plants so white as to almost glitter. And in a brilliant green square of field, a red square of naked dirt on the left, a double row of palms in between, with their dangling clusters of reddish-yellow fruit. Legitimate use, to be sure, from which I benefited and from which bit by bit the sea was getting saltier and fouler with algae and more selenium-tainted, creating carrion and carrion-stench, which kept seagoers away.

Legitimate use made the half-scorched rubble of the Sundowner Motel, whose rusty lonely staircase used to offer a vantage point across the freeway to Superburger and then out to the sparse pale house-cubes of Salton City. On a clear day one could see right across the Salton Sea from those stairs, but if there was a little dust or haze, the cities on the far side faded into hidden aspects of the Chocolate Mountains' violet blur, and then the stairs too were carried off by the myrmidons of desert time. Meanwhile the Alamo flowed stinking up from Holtville, with its painted water tower, and the Whitewater flowed stinking, and the New River bore its stench of excrement and something bitter like pesticides. And Imperial County flowered and bore fruit. Through that lush and luscious land, whose hay bales are the color of honey and whose alfalfa fields are green skies, water flowed, 90 percent of it not from Mexico at all, carrying consequences out of sight to a 380-square-mile sump.

From a distance it looked lovely: first the hand-lettered sign of may's oasis, then the Salton Sea's Mediterranean blue seen through a distant line of palms, and then the smell of ocean.

Novelist William T. Vollmann wrote about the Canadian Arctic in the July 1999 issue of ���ܳٲ������.��