The true great American pastime is bad-mouthing people from different parts of the country. We love to denigrate others whose realities in some way seem inferior to ours—and at no time is this habit more pronounced than when we’re talking weather. Late-summer heat brings out the worst of our mockery. “Why do those Northerners need a heat advisory for temperatures cooler than our average high?” Southerners deride. Of course, it also happens in the winter. Citizens of Denver, Colorado, roll their eyes when a dusting of snow shuts down schools in New York City.

This is not because Northerners in general and New Yorkers in particular are wimps. There really is a massive difference between weather alerts depending on where they’re issued. Let me explain.

The sends out dozens of watches, advisories, and warnings to alert us of hazardous weather and help us make decisions to stay safe. The alerts range from the mundane (a fog advisory) to the most urgent (a tornado warning).

Some of these alerts—typically those for the most extreme weather, like tornados—are the same no matter where you are in the country. Take a severe thunderstorm warning, for example: Authorities will issue one for a storm capable of producing hail the size of quarters or larger and/or wind gusts of 60 miles per hour. Those conditions will produce an alert whether you’re in Seattle, Washington, or Mobile, Alabama.

Then there are the relative alerts that vary county by county. A winter weather advisory is a relative alert. It takes only a dusting of snow in Pensacola, Florida, to trigger a winter weather advisory, but it takes four inches of snow in 12 hours to meet the criteria for one in Cleveland, Ohio. Much of that reasoning can be chalked up to infrastructure: Cleveland has the recourses to clear its streets after a blizzard. Pensacola, not so much.

Extreme cold and extreme heat are relative, in part, because we’re all acclimated to different temperatures. It’s easier for someone in North Carolina to suffer through three months of heat and humidity than it is for someone in Atlantic Canada to deal with it for a few days. “Stifling” is the default setting in Tampa for much of the year. If that city followed the same heat advisory guidelines as Ann Arbor, Michigan, or Burlington, Vermont, Tampans would basically live under a permanent it’s-too-hot-out warning.

A heat advisory is issued when an expected period of hot temperatures—either air temperature or heat index (the temperature you actually feel, taking humidity into account)—could pose a risk to those who are sick, elderly, or working outside for extended periods of time. An excessive heat warning is issued when dangerously hot temperatures are in the forecast that could cause heat-related illnesses even in healthy individuals.

The heat index routinely climbs above 100 degrees during the summer months in Miami. Using New England’s criteria, a heat advisory would be issued for Miami almost every day for months on end. But residents of the city are acclimated to the heat. Even vulnerable populations—such as the elderly and outdoor workers—mostly know how to handle the heat. On the other hand, wind chills dipping into the lower thirties are all it takes for a wind chill advisory in Miami. It takes a wind chill of minus 15 degrees and minus 24 degrees for at least three hours for NWS Boston to issue a wind chill advisory.

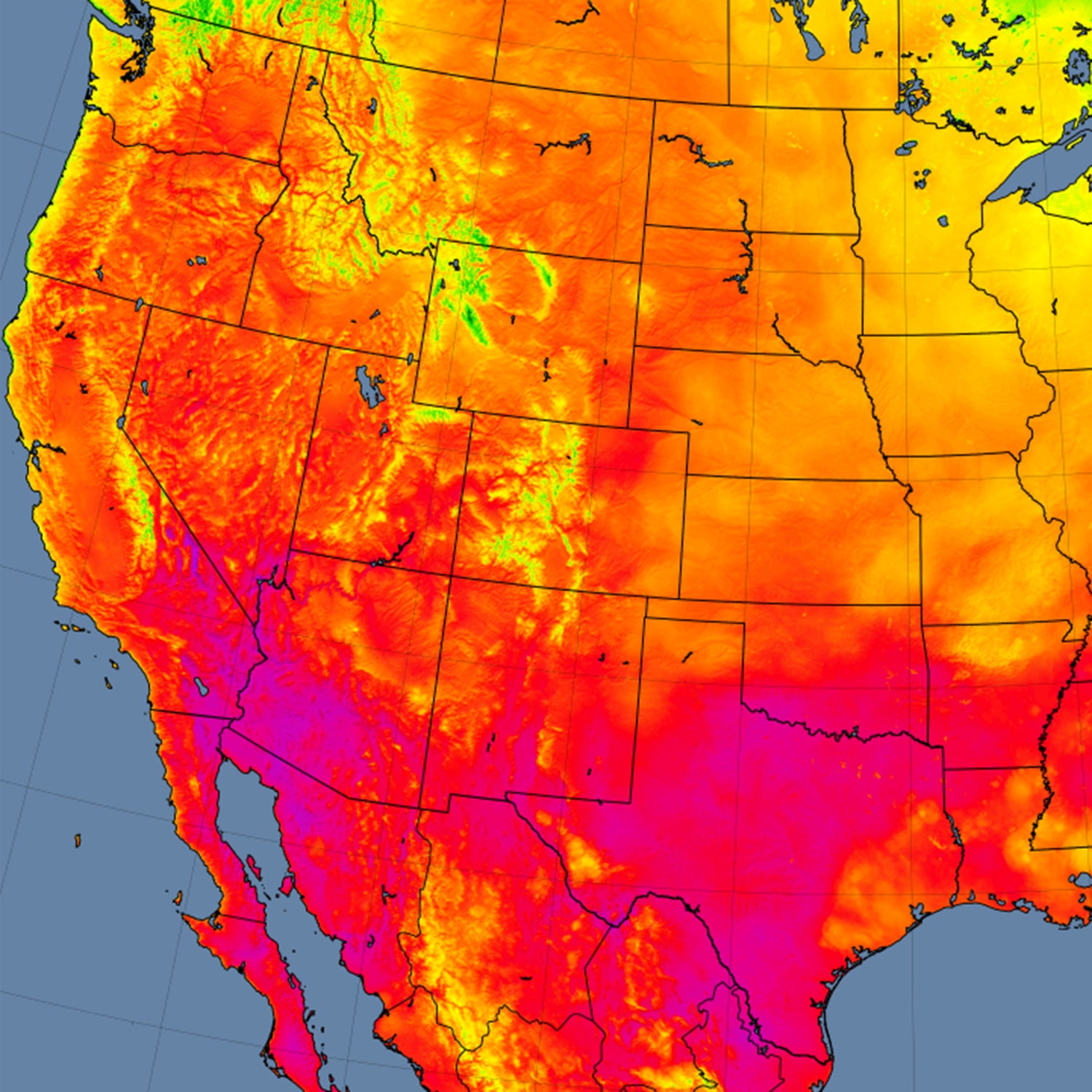

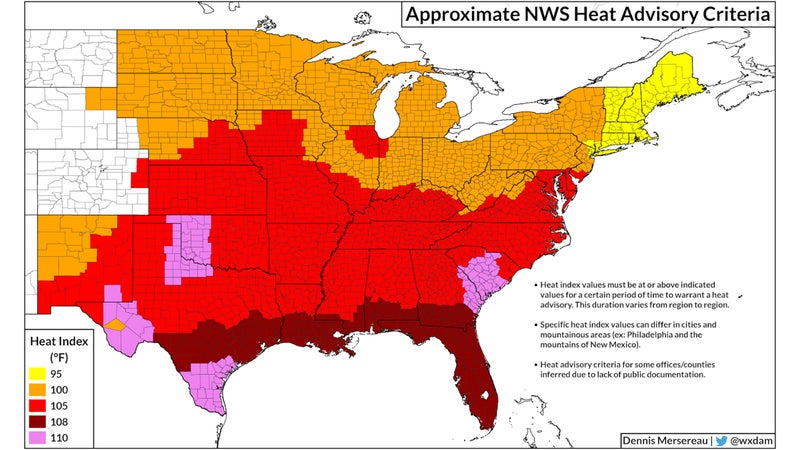

I did my best to map out the heat index required for a heat advisory for areas east of the Rocky Mountains. Many regional NWS offices—especially in the South and East—have their criteria helpfully laid out in various places online (see , , and ). Some of the heat index requirements on the above map are inferred based on the text of past heat advisories and the requirements of the surrounding offices.

So, let’s get into the data. It takes a heat index of 95 degrees or higher for a heat advisory to be issued in much of New England. The heat index (or air temperature) required for a heat advisory slowly rises the farther south you go. The criteria reaches 108 degrees along the Gulf Coast and 110 in desert areas of the southern plains. (The 110-degree requirement in parts of South Carolina and Georgia is due to these areas routinely seeing some of the hottest and muggiest days along the East Coast.)

The bottom line: It’s all a matter of what you’re used to. Get over it, wimps.