Since the bathhouse near the cabin where I live in Wyoming is closed for the winter, I haul cold water every day from the creek. The water must be heated for bathing and washing dishes, the stove requires wood, the rounds must be split, and the splitting makes you intimate with an eight-pound maul. Few things calm the mind like an hour with an eight-pound maul.

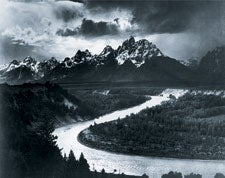

“The Tetons and the Snake River” (1942) by Ansel Adams

“The Tetons and the Snake River” (1942) by Ansel Adams

Around me is the ever-changing sky and the Teton Range, the mountains I love most. The rut is in full force. The bulls bugle, the cows answer with their little barks. The pronghorn are gathering for their journey back to the Green River. Geese and eagles are heading south. Three black bears have pestered me for a week; one of them was enthusiastic about pepper spray and kept coming back for more—two canisters' worth. The trout refuse every fly I've ever heard of. A friend got his elk on the first day of the season. It snowed for the first time since June, a storm I call the Winnebago because it sends all the RV folks south for the winter.

If there is fear around me in the wake of the terrorist attacks, it is not so much the fear of bombs or germs as the fear of a collapse of civil order. As a person primed by a diet of Richard Preston's The Hot Zone and The Cobra Event, and Stephen King's apocalyptic The Stand, I bought extra ammo for my sweet-shooting .270 rifle and my grandfather's 12-gauge. Batteries. Extra fuel for the chainsaw. A spare chain.

People have started doing strange things. A friend who traps deer mice with a Havahart trap talked to me about purchasing a 9-millimeter Glock pistol. There were reports of telephone calls from people in cities wanting to know if Jackson Hole was safe. At the stores in Jackson, part of the standard chitchat has become how safe Wyoming seems, especially if you come from a place where the population density is 24,000 people per square mile.

Despite setbacks in Somalia and Vietnam, we have endured and celebrated many victories—World War I, World War II, the Berlin Wall, the demise of the evil empire—but our historical trajectory now seems headed into a worrisome labyrinth. So some people smoke more, some drink more, some decide not to get divorced after all, some start going to church again, some just watch it all happening on television. And some, like me, go into the wilderness.

��

I've always gone into the wild during trying times. When I was a kid, I would hunt and fish near my home in Oceanside, California; later, I'd take long solo trips climbing or on snowshoes into the mountains of Colorado. During the midseventies I spent over a year in northern Pakistan, much of it in the mountains along its border with Afghanistan. I was an unhappy academic in Chicago enduring the remains of a broken marriage, and my home wilderness in Wyoming and Utah seemed insufficient to my needs. When the adventure outfitter Mountain Travel offered me an opportunity to help lead a trek to K2 in Pakistan in June of 1975, I went. Afterward I turned west and spent the rest of the summer traveling in the Hindu Kush, a place I told myself was real wilderness, the kind that could soothe a battered heart.

I visited Hunza. I wandered west from Gilgit to Yasin, then north into the mountains along the Wakhan corridor, the narrow sliver of Afghanistan that leads to the border with China and is adjacent to Tajikistan. Then I walked and rode jeeps south down the Yarkhun and Mastuj Rivers to Chitral, and on to the dreary town of Drosh, and then back up into the mountains to Malakand and by bus to Peshawar. Beyond Drosh the river plunged down a valley into Afghanistan and became the Konar, which in roughly a hundred miles joined the Kabul River near the then-obscure town of Jalalabad.

The land was like Death Valley, but higher. Vast mirages covered the valleys. The passes were sometimes 15,000 feet high, broad saddles veined with ancient trails. The mountains rose another mile or two but were often obscured by dust storms. The only trees in the high mountains were dwarfed birch.

The border with Afghanistan was guarded by soldiers, but their presence back then was merely symbolic. The guard station at the top of the Yarkhun Valley consisted of two men, one horse, a flintlock rifle, and a hand-cranked radio. One of them was reading—somewhat optimistically, I thought—a volume of Rommel's letters. In broken English he railed at us about American support for Israel at a time when “the Jewish infidels” had invaded Uganda. Uganda? He insisted on it, pointing to his radio. When I reached Islamabad, I learned of the commando raid at Entebbe.

The people inhabiting the villages in the northernmost valleys of Pakistan were farmers, masterly irrigators who were invariably kind and helpful. Some of the older village leaders had been educated at English schools at Srinagar, in Kashmir, before the partition of Pakistan from India in 1947. They wore Harris Tweed coats over their flowing Pakistani clothes, and several smoked English pipes. They hunted with modern British and German rifles. Occasionally they would show off fine markhor horns, a snow leopard skin, or an ancient scimitar.

At their invitation my groups and I often ate yogurt and paper-thin chapatis off silver platters arranged on old carpets spread on lawns beneath mulberry and apricot trees. Their tone was one of interest and amusement that Americans would come so far. For what? Just to look? To find what? Wilderness? They did not know that word. Beauty they understood, but it was faraway, in the cities, the beauty of fine mosques, mosaics, carpets.

And indeed it was not wilderness, it was their home. Much of the land was like what Thoreau, in The Maine Woods, called wild pastures, a blank on the map with few roads and little population but lined with trails and munched on by goats for thousands of years. The forests were logged to the point that many valleys looked like they'd been clear-cut. The game, especially predators, had been hunted almost to extinction. Nowhere did I find the carpets of flowers, the crystalline streams, or the concentrations of wildlife I so loved in Wyoming. When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, refugees poured over the passes and up the Konar River into Pakistan. Trekking and climbing along the border came to a virtual halt. Eventually, I came home.

��

A few years later I settled into guiding for the Moose, Wyoming-based Exum Mountain Guides and was living in a cabin in Grand Teton National Park. It had suffered the same fate as the valleys of the Hindu Kush, although here the damage was limited to a hundred years of grazing. Sheep chewed their way through the Wind Rivers and the west side of the Teton Range; cows did the same in the Escalante, the Gros Ventre, and the east side of the Teton Range. But with the creation of national parks and the Wilderness Act, the land and its diversity, for the most part, had come back.

I became less concerned with the new and novel and more concerned with attaining an intimacy with what was at hand, in my home wilderness. I wanted a haven, my own safe place, thoroughly known and loved, however vast and empty—a place removed, as it were, from human history and its vicissitudes. I thought about my nation's foreign-policy record of oscillation between engagement and escape, commitment and separation, and of my own struggle, of how much, or how little, to engage with the world.

I was in search of places that were indifferent to the incessant march of human foible, the unending political squabbles, the putative reality presented each moment by CNN. And yet, I soon discovered, there is no escape. The truth expressed by Muir and Leopold and ecology, by modern physics and Buddhism—that everything is connected—is unrelenting. After the tragedies of September 11, we are almost unbearably conscious that remote forces, of which we are only marginally aware, might suddenly determine our fate, the fate of our families, the fate of our friends. And being far from human tragedy is comforting only if you maintain a rather solipsistic stance toward the well-being of those you love.

When the planes flew into the Pentagon and the World Trade Center, a friend's son was in Kazakhstan working on a thesis in geology; another friend's son was in charge of a Navy SEAL team; another friend was flying from Boston to Montana that morning and was grounded in Michigan. Like virtually everyone else in America, my friends and family live far away—in Washington, D.C., Seattle, California, Utah, Colorado, and Hawaii—and there is no escape for any of us. Still, I believe that living in a meadow in the Tetons had a certain advantage on that sad day and in the sad days that followed. I have no television and my modem is too slow to run videos, so it wasn't possible for me to watch the interminable replay of footage that feeds our addiction to tragic events. I wanted to shed those images instead of magnifying them; to be informed, not inured. The means to do that was near and known. I went to the wild places I have gone to for 40 years.

I went up the Gros Ventre River and into the wilderness, walking up the stream where I caught my first Wyoming cutthroat many years ago. I said I was looking for hatches, but mainly I was throwing sticks in the creek for my dog and wondering what my heroes, the hermit monks and poets of ancient China, would have done about anthrax and the Taliban. They lived in a time of great strife: a civil war, the suppression of Buddhist monasteries and practice. What did they write about?

I climb the road to Cold Mountain,

the road to Cold Mountain that never ends.

The valleys are long and strewn with stones,

the streams broad and banked with thick grass.

Moss is slippery, though no rain has fallen;

pines sigh, but it isn't the wind.

Who can break from the snares of the world

and sit with me among the white clouds?

����������������—Han-Shan

Wang Wei wrote a book he titled Laughing Lost in the Mountains. Whenever I get too serious I like to remember that title. I was rather lost myself by the creek in the Gros Ventre when suddenly a shadow passed over me and tore down my little valley faster than any bird could fly, ever. Then the blast, shattering and implacable. As the dim glow of the afterburners disappeared over Lavender Ridge, my wild valley transmuted into a landscape out of Top Gun.

��

The vice-president and his retinue had arrived in Jackson Hole aboard Air Force Two, accompanied by helicopters, squads of Secret Service agents, and jets to patrol the airspace around town. And patrol it they did: around and around all day and night and all day again. But I still had a slew of other places to go, my collection of havens.

My mate and I went to the Green River Lakes in Bridger-Teton National Forest with our dog, paints, and books. We loaded the canoe and paddled up the first lake, then waded and hauled the canoe up the creek toward the second lake. It was so shallow I was stepping on sculpins. Two men with horses had a camp at the other end of the lake, but they left just after we arrived. We set up our tent and drank hot toddies on the sandy shore and watched the light fade from the great cliffs surrounding the summit of Square Top. We didn't come home for two days.

And soon I left again. I walked alone up the lower face of Teewinot, the Teton peak that rises just west of my cabin, across the meadow. I followed an old climbers' trail, unsigned, unmarked on the maps. It leads over talus and avalanche debris and onto a broad ridge. I paused at the waterfall just off the trail, a place I always visit. Just a trickle now. Then I climbed into the forest until I reached the first whitebark pines—my favorite trees. I settled there and looked around.

Things have changed since September 11, we've heard it said, again and again. Yes, and we are all obliged to speak and act in this newly dangerous world. But at the same time, I find a measure of relief in the things that haven't changed: the geese that fly south in the autumn, the fir that resists the maul, the winter that has arrived, and the spring to come. I can see a hundred miles of open spaces, mountains and rivers I know and love. The only sound now is the caw of a Clark's nutcracker.

��