OF THE WORLD’S 36 SPECIES OF WILD CATS, none has a more powerful bite than the jaguar. Its skull, wide like a cinder block and wrapped with muscle, is engineered to crush. Its snout, short and compact, generates enough leverage to crack a tortoise shell like an egg.

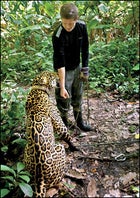

Thayer Walker with jaguar

The author with his 260-pound jaguar

The author with his 260-pound jaguarVolunteer with jaguar

A volunteer and a jaguar rest during a walk

A volunteer and a jaguar rest during a walkWith these tools, the jaguar has perfected a devastating method of dispatch: the cranium crunch. Wrapping its jaws around its prey’s head in some cases nearly as large as its own the cat drives its two-inch canines through more than half an inch of bone to puncture the brain. On other occasions, a jaguar pierces the skull through the ear canal, leaving no visible entry wound.

Until recently, the mechanics of a jaguar’s bite were little more to me than an academic abstraction. That changed quickly when I visited a Bolivian animal-rescue organization called Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi (CIWY). CIWY rescues wild animals like monkeys, birds, pumas, and jaguars from Bolivia’s black market; the animals might come from abusive situations or well-intentioned people who simply can’t care for them. One of CIWY’s goals is to rehabilitate the animals and, when possible, to release some of them within the park. But that’s not done with the big cats, in part because of the potentially severe consequences of a mishap.

��

A handful of Bolivians steer this ark with the help of international volunteers, and to make the cats’ life sentences more enjoyable, the organization promotes a practice called “direct contact.” For six to ten hours a day, live-in volunteers many of whom have no more expertise with animals than what they’ve gleaned from a family dog and Animal Planet walk these predatory felines on a leash through the jungle. For the next 11 days, I will, too.

Shortly after arriving at Parque Ambue Ari, CIWY’s 1,991-acre jungle compound in the central-Bolivian department of Santa Cruz, I am assigned to Jaguarupi. His name is derived from an indigenous word that means “little jaguar” the same ironic humor that lends itself to 300-pound bouncers nicknamed Tiny.

“Rupi” came to Ambue Ari from a private residence as a cub in 2003, soon after the park opened, and now he’s the biggest cat on the block, a 260-pound alpha male. At least two volunteers work with Rupi, so after signing a waiver stating that jaguar wrangling “leads to an inherent risk of injury or accident,” I’m paired with 23-year-old Adir Michaeli, who’s one month into a three-month stay and therefore our team expert. With a sturdy chin and thick black eyebrows, Michaeli looks like an Israeli Colin Farrell. Having spent four years as an explosives specialist in the Israel Defense Forces, he has chosen jaguar walking as his method of relaxation.

On our way to Rupi’s cage, Michaeli launches into a safety briefing: Don’t touch the jaguar. Don’t yank on his leash. When he jumps you, don’t fight back, as it will only encourage him (and you won’t win). Never turn your back on him. Try not to let go of the leash. Don’t let him smell your fear. And don’t ever, ever forget: He could kill us both in seconds. Have fun.

I am now qualified to walk a jaguar.

WHEN WE ARRIVE AT Rupi’s enclosure, a 12-foot-tall chain-link fence wrapped around more than 1,700 square feet of jungle, he is sitting sphinxlike on a raised wooden platform. Even from a distance he looks massive.

Two sets of doors stand between us. Michaeli opens the outside gate, closes himself inside, and opens the inner gate. Rupi joins Michaeli and eagerly licks his hand while he clips the leash 20 feet of rope with a carabiner at the end to his collar. At Michaeli’s signal, I swing the outer gate open and hold my breath. Rupi ignores me.

Michaeli holds on to the front of the leash near Rupi’s collar and instructs me to follow close behind and wrap the end of the rope around my hand in case Rupi decides to bolt. The next 90 minutes pass quietly, with Rupi sniffing, spraying, and trotting through his territory, roughly two miles of jungle trail cut something like a figure eight.

��

When I take Michaeli’s place at the front of the leash, things get interesting. Rupi starts to run, and I slacken the leash to avoid choking him, freedom he takes to leap on a tree and use the trunk as a springboard to launch back at me. He slams me to the ground, and every sharp part of his body touches every vital part of my own. Rupi wraps his mouth around my thigh and then my neck; he brushes my crotch with a claw and then buries his face in my stomach, as if sniffing my intestines through my belly button.

Then the world turns a slobbery black. Rupi spreads those skull-crushing jaws wide and wraps them around my face. His canines press into my temples and into my cheekbones just below my eyes. His hot breath seeps through my eyelids. When his tonsils finally cease to blot out the sun, I see the jaguar standing on my chest with his head, golden and spotted, held aloft in victory.

Michaeli plays the rodeo clown and rustles about enough to distract the cat so I can sit up. Still, Rupi begins the preliminary steps of arthroscopic surgery on my knee with his mouth. My best defense, Adir has told me, is to cram my forearm in his mouth (“If your arm is in his mouth, it means your head isn’t”). After two minutes of jaguar jujitsu, Rupi rolls off me and resumes his walk, as if nothing has happened.

This has been not a bloodthirsty attack but an act of play and dominance, and despite the fact that the cat nearly swallowed my face, I stumble away unscathed, save a small scratch on my hand. As we finish our walk, with Michaeli again in front, I ask if mine was a typical introduction.

“I’ve never seen that before,” says the explosives expert. “Usually the person ends up on the cat, not the other way around. That was really special.”

AS FOUNDER JUAN Carlos Antezana tells it, the origin legend of Comunidad Inti Wara Yassi is nearly as fantastic as its day-to-day operations. It begins with a drunken spider monkey.

Antezana is a loquacious 51-year-old, round, excitable, and oddly reminiscent of the spectacled bear, Balu, that lives at one of his parks. In 1985, he began teaching local orphans and poor children subsistence skills, like sewing and cobblery, around his home in La Paz. He’d take the kids on camping trips, and in 1993 he led thousands through the streets of La Paz to celebrate Earth Day. In the following years, Antezana toured the country with a youthful congregation, preaching environmentalism.

On one such trip, the group passed a bar where a beer-drinking spider monkey provided the in-house entertainment. The kids pooled their money, bought the monkey, and released it in the forest outside of town. Drunk, disoriented, and dying for a stiff drink, the monkey, they later learned, stumbled back to civilization. It had no other home.

The Bolivian black market teems with wildlife, so in 1996 Antezana, along with CIWY vice president Tania “Nena” Baltazar, created Parque Machia, a 93-acre jungle reserve on the fringes of the town of Villa Tunari, as a place for Bolivia’s legion of mistreated once-wild animals. “We learned by doing,” says Baltazar, 35, who, like Antezana, has never had any formal animal-care training. “We had no money, a sleeping bag, four monkeys, and a lot of love.” Soon, they had more company.

When a circus rolled through Villa Tunari, Antezana got wind of a pair of mistreated macaws. He wanted to rescue them, so he followed the circus from town to town for 15 days before he finally found authorities sympathetic to his cause.

The circus also had a young puma that, says Antezana, the ringleader had been forcing to leap through hoops of fire. When the puma refused, his back legs were broken. Antezana saw the injured animal, scooped him into his arms, and sped to the city of Cochabamba in a 4×4. There he bought two bus tickets one for him and one for the feline and spent four hours sitting next to the 60-pound puma on a crowded coach bound for Machia. Inti Wara Yassi had its first cat.

Over the past 13 years, CIWY has rescued thousands of animals, and it opened a third park this summer. Largely funded by volunteers and private donations, the organization does not receive monetary support from the Bolivian government, though animals seized by government raids often end up in its care. In 2006, Antezana was chosen as one of five passionate conservationists featured in Animal Planet’s Jane Goodall’s Heroes, and received $5,000 to continue his work.

CIWY posts fliers at travelers’ hostels throughout South America, and word of a Real World meets Grizzly Man parallel universe has percolated through the backpacking community. I heard about it from my cousin, who spent three months at Machia. Anyone who plunks down $280 or so to stay for a month purchases room, board, and the privilege of walking a cat. The cats get exercise, the volunteers get an unforgettable experience, and CIWY gets a steady flow of income to care for the animals. Everybody wins. All you have to do is leave better judgment at the door and step into the jaws of a jaguar.

Exotic-cat sanctuaries abound in the United States, but there’s nothing like CIWY. Organizations range from roadside attractions where people can get their picture taken with a tiger to refuges that are closed to the public and keep cats in large enclosures without human contact. The U.S. Department of Agriculture prohibits the “exhibition of such animals without sufficient distance and/or barriers between the animals and the general viewing public.” In Bolivia, the country’s Ministry of Biodiversity and Protected Areas announced new regulations last spring that will require rescue centers to adhere to certain licensing and infrastructure standards the first step in a long process of adapting laws to hold animal-rescue centers to an enforceable standard but CIWY volunteers will still be allowed to walk cats. Bolivia has animal-trafficking laws but until May had no policy governing operations like CIWY.

Not a single expert I spoke with regards the concept of inexperienced volunteers walking apex predators through the jungle as even a distant relative of a good idea. “I would never let anyone I care about do something like this,” says Toronto-based zoologist and cat trainer Dave Salmoni, most recently the host of Animal Planet’s Into the Pride. He’s spent months trailing a pride of wild lions on foot and trained captive-bred tigers for release into the wild. “Cats are pure predators. Their body tells them that they want to kill. There are too many stories of hand-raised cats behaving well their entire lives until they kill someone.”

In 1999, Salmoni nearly met that fate when a lion he’d worked with for about a year tried to tear his throat out. Last January, at Maryland’s Catoctin Wildlife Preserve and Zoo, a jaguar mauled a zookeeper after the animal’s enclosure was left unsecured. In 2007, a zookeeper at the Denver Zoo suffered fatal neck and spinal-cord injuries from a jaguar attack. Perhaps the most famous cat mauling occurred in 2003, when a hand-reared tiger dragged Roy Horn, of the Las Vegas magic act Siegfried & Roy, offstage by the neck, nearly killing him.

“There’s risk for people working in Darfur,” says Jonathan Cassidy, director of Quest Overseas, a British travel company that has sent more than 250 volunteers to CIWY since 2003 and helped finance the purchase of Ambue Ari the year before. “The important thing is to manage expectations.”

When asked about their own perceptions of danger, CIWY volunteers replied with surprising naïveté and chilling prognostications. “It’s just a big cat,” says one. “It’s only a matter of time before someone gets seriously hurt,” counters another.

THE CAMP AT AMBUE ARI exists in a sublime equilibrium of disrepair and expansion: Brick-and-concrete buildings, half complete, stand near wooden structures in near collapse. Even a moderate burst of rain turns the compound into a shallow marsh, and due to limited water pressure, the outdoor faucet and the indoor shower have a frustrating relationship of inverse functionality. Volunteers sometimes sleep with the animals before he died, Faustino the howler monkey lived in one dorm, and jungle pigs hole up beneath another and the mosquitoes are a biblical plague.

The park, CIWY’s second, opened in 2003, and when I arrived it housed four ocelots, five jaguars, 13 pumas, and a menagerie of monkeys, birds, and other South American creatures, all cared for by more than 40 international volunteers. Noemi Castaños, the Bolivian general coordinator, oversees volunteers and the cats, and park director Zandro Vargas is the round-the-clock veterinarian. Despite the tough conditions, CIWY estimates that more than 35 percent of the volunteers return to the parks, and some people have spent years with the organization.

Mornings at Ambue Ari begin with hard labor, and the afternoons offer little relief. In addition to animal care, volunteers are responsible for upkeep of the property; at 7 A.M. sharp, while women tend to feeding chores, men carry 100-pound wood planks into camp, cut from deadfall, to be used as building material.

The walks begin around 9 A.M. and last three and a half hours, or until Rupi feels like going back into his enclosure. (We coax him in every day with a raw egg.) Each cat has its own trail, so we don’t run into other cats and volunteers. There are no fences around the park’s perimeter, and Rupi, like other cats, has broken free from volunteers and returned numerous times. After lunch, we walk Rupi for another three or four hours until he’s ready to get back in his cage for dinner: nine pounds of raw chicken or steak.

The routine helps the animals and the volunteers become more comfortable. “If you work with these animals for long enough, you lose your fear,” another Israeli, 26-year-old Jonatan Karny, tells me one humid night as we sweat off a dinner of overcooked starch in the camp’s dining block. “I think of it like I’m a construction worker on a skyscraper. My job is to walk on this beam. I respect the beam, but the less scared of it I am, the safer I will be.”

After just a few days at Ambue Ari, as Rupi and I get familiar, my persistent fear of death subsides into sporadic bursts of nervousness. Rupi keeps a casual but constant pace. On the hottest days, he swims in the river and lolls around on the bank, but these breaks rarely exceed 20 minutes. The behavior is instinctive. The jaguar is a great wanderer. With a range from northern Argentina to the southwestern United States, the world’s third-largest felid (behind tigers and lions) is the only widely dispersed big carnivore that has not divided into subspecies. These rambling ways have allowed them to spread their DNA throughout the New World, and there is little genetic difference between a jaguar in Arizona and one in the Pantanal.

Rupi has no doubt about his standing atop the food chain. He moves with the confidence and nonchalance of royalty and commands the same respect. Whereas other cats readily show affection by licking, cuddling, and even napping with their volunteers, Rupi’s displays of warmth are generally limited to a playful head butt to the crotch. He is a king, not to be fawned over but to be admired.

He does, however, offer fleeting moments of tenderness, most commonly as I let him out of his cage. In the tight quarters between the double doors, he’ll rub his cartoonishly huge head on my knee my signal to cop a quick feel through his short, coarse fur and massage the thick folds of his skin with my fingers.

Michaeli enjoys an even more intimate relationship with Rupi. One afternoon, while taking the cat out of the cage, he bends down and offers his head to the jaguar, which gently responds by using Michaeli’s face as a salt lick.

“Now you’re just showing off,” I jab.

“I know what I’m doing,” he fires back between slobbery osculations. “Let me enjoy my cat.”

IN AUGUST 2006, CIWY received a jaguar that would change the organization irrevocably. She was an ill-tempered two-year-old whose disposition was molded by a cruel life of confinement in a small steel cage. La Paz authorities had seized the cat from a private residence and turned it over to CIWY on the conditions that the organization would get government permission if it wanted to move her and would alert the government when she died.

CIWY named her Katie and gave her the largest cage at Machia. But even that luxury proved restrictive, since the jaguar was too dangerous to let out. In April 2007, CIWY attempted to transfer her to Ambue Ari, where she’d have more space. Katie never made it out of Machia; she was tranquilized for the move and never woke up.

CIWY hadn’t notified the government about the transfer attempt and didn’t tell it about the death even though they claim the cat was killed by what should have been a safe dose of anesthetic. A CIWY autopsy revealed an unknown preexisting condition that contributed to her demise: Dead tissue covered the cat’s shriveled left lung and half of the right one.

Several weeks later, CIWY obtained a new jaguar and named her Katie. The incident remained buried at Machia until the spring of 2008, when a disgruntled former worker alerted Animales SOS, a local animal-rights group, which leaked the story to the press. Accusations of a $200 payment for the new jaguar emerged, and an organization dedicated to animal rescue was suddenly being accused of animal trafficking.

Baltazar maintains that the new cat was donated, that the only money that exchanged hands was for the cost of transporting the animal, and that CIWY named her Katie to honor the deceased. The only mistake CIWY made, she insists, was not telling the government about the death. “We panicked,” says Luis Morales, a longtime vet who recently retired from CIWY. “It was a great mistake not to have informed the government.”

Animales SOS director Susana Carpio worked with CIWY for years before the Katie incident, but she now sees the event as an example of wider practices of irresponsibility and cruelty at the park. “They do a terrible disservice to the animals,” says Carpio. “It’s a big clown show, and because of this clown show, animals are dying.”

Because it failed to honor the agreement signed when Katie went to CIWY, the park has been temporarily prohibited by the government from releasing, accepting, or transporting animals without permission. “We are cooperating with the investigation and presenting everything that we have,” Baltazar says.

“The veterinarians who work here are very professional,” she says. “Many of the animals come to us abused and mistreated, and we do absolutely everything we can to keep them alive. We’re not negligent in any sense.”

Still, some have chastised the organization. Zoologist Dalma Zsalako, a volunteer coordinator at Hacienda Santa Martha, a wildlife refuge in Ecuador, abhors the idea of wild animals being treated like pets. “I am against putting leashes and collars on wild animals,” she says. “We are a rescue center. We are trying to rehabilitate these animals, not domesticate them. We have dogs and cats for that.”

Ambue Ari is underequipped to handle any major emergency that might arise. All the parks have full-time vets who treat animals and volunteers’ minor injuries, but Ambue Ari is off the grid. There’s no communications system the nearest phone is a five-mile hitch or bus ride away and, when I was there, no evacuation vehicle either, other than a motorcycle.

Whenever I asked Baltazar and Castaños about past cat-related volunteer injuries, they would offer some variation on “Just a few stitches” or “The monkeys are more dangerous than the cats.” I polled dozens of volunteers past and present, and no one shared any horrific tales. But there is a written record that alludes to slightly more. Every cat has a notebook that volunteers write in for the benefit of those who follow. One night, flipping through the book on Sama, a jaguar that volunteers are no longer allowed to walk, I came across a 2003 entry that described a volunteer who suffered, among other injuries, a deep cut on the inner thigh, which required 17 stitches. Six months later, the book notes, another volunteer required five stitches.

When I inquire about these incidents, Baltazar says, “I don’t remember everything, or maybe I remember only the good things.”

Meanwhile, CIWY’s supporters vociferously defend the organization. A group of Chilean veterinary students were in the midst of 16 days of practical work at Ambue Ari when I arrived, and they lauded the conditions. “The quality of life these animals enjoy is better than any zoo I’ve seen in South America,” said 22-year-old student Francisco Cordova.

My impression of Ambue Ari was that of a group of hardworking, well-intentioned people with limited resources doing the best they could to rehab wild animals. I saw no signs of abuse or animal mortality. Though CIWY clearly needs more infrastructure and scientific expertise, its rescue centers for black-market animals are the largest in the country and serve a crucial role. “The ministry supports these kinds of initiatives,” says Omar Rocha, director general of the Ministry of Biodiversity and Protected Areas, “but we need them to comply with legal and technical requirements.”

“Animal welfare is at the bottom of Bolivia’s list of concerns,” says Quest director Jonathan Cassidy. “What they have pulled off is a minor miracle.”

WALK WITH A JAGUAR long enough and you begin to think like one. Landmarks cease to exist within their own context, usurped by the role they play in the cat’s universe. That log on the trail isn’t a fallen tree but a hardwood scratching post that Rupi gleefully reduces to sawdust with naked claws. The meniscus of flooded lowland isn’t just a marsh; it’s Rupi’s bathtub, where he dips on a hot afternoon.

My fourth day with Rupi begins with a storm. It’s a welcome respite from the thick equatorial heat, but Michaeli predicts it could spell difficulty for our walk. We are joined by a third volunteer, Australian Aaron Zycki. I grab the front of the leash, and ten minutes into the walk, with Rupi sniffing around crack! a rotting 25-foot tree falls, and Rupi bolts. Falling trees and panicked cats are not in the jaguar training manual. In a split second, I decide to release the leash, which proves to be a good thing. Rupi narrowly escapes being smashed by the trunk, though some of the smaller branches hit his flank.

Michaeli, Zycki, and I stand frozen with fear: If Rupi’s idea of a pleasant salutation borders on feline rape, what’s his response to getting hit by a falling tree? Rupi drops his head and stares us down. No one moves. Rupi takes a slow step toward us, shakes it off with a little shimmy, and proceeds with the walk as if nothing has happened. Good cat. Good, good cat.

Like the court jester who constantly tempts fate with his volatile king, it’s hard for me to leave a situation that any fool knows could end badly. Walking Rupi is humbling, energizing, addictive any trepidation is overwhelmed by the narcotic effects of mainlining 1.5 million years of predatory instinct through a frayed leash cinched at my wrist.

A few days later, Rupi rips out the crotch of my pants with his teeth. I happen to be wearing them at the time. It’s a warm, calm morning, but Rupi makes no secret that we’re in for a wild ride. Lying on his side at the edge of a clearing, he springs into the air with half an effort, clears the top of an eight-foot-tall stand of plants, and takes off down the trail, with Zycki and me following behind. A few minutes later, he leads us back to the clearing, leaps on Zycki’s back, and then turns his attention toward me. He sweeps me to the ground, sinks his teeth into the fabric of my pants, and shreds the crotch.

This is just play for Rupi, but I’ve never seen him so riled up. He bats me around on the ground for several minutes until Zycki finally clips the leash to a tree and I manage to escape when the rope pulls taut. We let him unwind for half an hour, until he finally calms down enough to return to his cage.

Back at camp, I run into an English volunteer named Rob, who’s on his way to walk a 170-pound jaguar he’s been working with for nearly a month. I tell him what happened and then pose a question I’ve been grappling with since my arrival:

Is Ambue Ari a black hole of rational thought, a crazy patch of jungle where common sense goes to die? Or is this a center of enlightenment, where compassionate people care for animals with tortured pasts and repent for the sins of humanity?

“It depends on the kind of day you’ve had,” he replies. Then he walks into the jungle, where his jaguar awaits.