The National Park Service has dealt with controversy over issues ranging from climbing access to land-use, but when news broke that agency director Jonathan Jarvis halted a plan to ban single-use plastic bottles in the Grand Canyon, hackles were raised—both inside and outside the agency. Jarvis, an NPS careerist, has led the agency since an appointment by President Obama in 2009. We spoke with him about his decision on the bottle ban, the agency’s climate change initiatives, and the policing of public lands.

Jonathan Jarvis

Johathan Jarvis

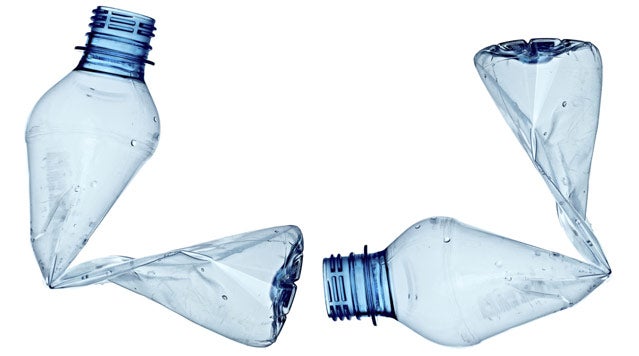

Johathan JarvisStephen Martin, the architect of a plan to ban the sale of single-use water bottles at the Grand Canyon, he believed the halt of the ban was due to the NPS being “influenced unduly by business”—specifically Coca-Cola, which sells Dasani bottled water and is a major donor to the National Park Foundation. You’ve denied this, saying you’re concerned with the park’s visitors having easy access to water, given the desert landscape. How was that concern addressed?

The role of the director of the National Park Service is to provide oversight over the broader National Park system. We have 397 units of this system—some of them are quite small, actually most of them are quite small, we have a lot of medium-sized parks, and then we have a few large, iconic parks like Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Everglades, and a few others.

So my intervention with respect to the Grand Canyon water bottle issue was because the Grand Canyon…has a tendency to set a precedent service-wide. We didn’t really have any service-wide guidance on how to approach this. The Canyon has the financial resources to be able to install alternative water resources in a number of areas all over the park. Other parks don’t have those kinds of resources. So what I wanted to do was to say, “Okay, hold on Grand Canyon, let’s step back.” Let’s take the chance to develop service-wide policies that can guide parks across the country. We , giving the opportunity for basically all the parks out there to ban water bottles, but in more of a comprehensive approach to overall sustainability.

I think Grand Canyon will go forward and execute a ban, and I’m perfectly comfortable with that, as I will be with other parks as well. [Editor’s Note February 7: Intermountain Regional (IMR) Director John Wessels the Grand Canyon’s petition to ban the sale of individual-use water bottles.]

How do parks manage how much water they need to make available?

In my policy, each park, as it goes down this path of consideration of elimination of water bottles being sold, they must do an analysis of water availability. The old days of running a garden house out there, off your spigot, and letting visitors take that water, are gone. We need to ensure, through public health surveys, that the water is tested, that the water is potable, that we’re not pushing the public into drinking water from sources that might result in them getting Giardia or any other kind of contaminant. So the park superintendents in the field are the best [people] to do that, but the National Park Service also has a public health service that helps us with our water testing to ensure the water is safe. I think that is something each park has to do before they eliminate the sale of water bottles.

Can you tell me a bit about specific programs the National Park Service has adopted to adapt to a changing climate?

Within many units of the National Park System we’re already seeing the effects of climate change. Whether it’s the glaciers melting in Mount Rainier or rain-on-snow events in the Cascades, the intensity and length of fire seasons in the Sierras, storm surges on the coastal systems, what we’re facing is a higher degree of variability in climate. We’ve been able to live a long time with a fairly predictable climate and that is all being changed. So the Park Service is going through four focus areas within our overall climate [change] response, and one of those is adaptation.

Within adaptation it’s really to begin to do vulnerability assessments in terms of critical resources that may be lost or impacted as a result of climate change, for example through sea level rise. Say you’re in a coastal park; we have expectations of sea level rise in the foreseeable future. What resources might wind up being under water? It could be a cultural resource, such as an archeological site, or a pictograph, or it could be man-constructed site like Fort Jefferson down at the tip of the Florida Keys. We’re doing scenario planning based on that to figure out how we’re going to adjust our activities and our investments, and even our surveys for certain species.

I characterize it in very simple terms, in terms of sea level rise: look uphill from where you are today, because you may have a salt marsh—an incredibly important coastal ecosystem and we might have blocked the next area uphill from that which might become the next salt marsh, as sea level rises. So adaptation, scenario planning, and building into the system resilience and redundancies so we can ensure that these ecosystems persist through the climate change we expect.

The NPS is making efforts to provide education and support for rangers who want to incorporate issues relating to climate change into their public talks and programs, but a four-day training course in climate change science and education last year. Is anything being done to boost attendance at these training sessions?

There’s an old tradition of people from the National Park Service flying across the country and meeting in windowless rooms to talk about the outdoors. We’re changing a lot of that in terms of online resources. We’ve been conducting a series of webinars with climate scientists, our scientists, our field staff, and our interpreters, to deepen their understanding and ability to talk about climate change specific to the parks where they work. So it’s not all about creating a training course and flying people to a training center to teach people how to talk about climate change. We’re using technology, media, webinars, and developing guidance documents like our climate response guidelines—and all of those are being distributed around the park systems so that we can deliver a unified message around climate change.

Are you finding that there are generational gaps in climate change understanding between older and younger rangers?

The great thing about our interpretive workforce is that even though they have a wide variety of educational backgrounds, they develop a deep knowledge and expertise about the resources they are talking about when the visitor is there and expects to hear the unvarnished truth. So I have great confidence in them.

I did a talk a number of years ago, titled—with all apologies to Al Gore— Climate science is often dry and is often presented in terms that are difficult and challenging for the public to get their arms around. But to bring climate change down to a personal level, there’s really no better place than the National Parks, people have a deep and emotional connection to the National Parks and they are often repeat visitors. And so the opportunity to demonstrate before the public the changes that are happening on the ground, during the intervals between their visits is a perfect opportunity to talk about that. Take a place like Mount Rainier, where generations of families have come to visit. One of their favorite memories might be the ice caves. Well, the ice caves are gone. So when families come in and say what happened, that’s the opportunity for you to come in and talk about climate change and the effects within the National Parks.

The proposed (HR 1505) would allow the Department of Homeland Security to maintain and construct roads, fences, and monitoring equipment within 100 miles of our borders with Canada and Mexico while prohibiting the Secretary of the Interior from taking action on public lands that impede the border security activities. Have there been conflicts between the U.S. Border Patrol and NPS staff in these border areas?

I’m not going to speak to specific legislation. But I will tell you the National Park Service has been operating on the U.S. border with Canada and Mexico for 100 years. And we’ve had long and deep cooperative relations with the Border Patrol and the Department of Homeland Security. Now obviously there are some areas of the border that are greater challenges than others, so I think a case by case and park by park approach is appropriate, and not one size fits all [approach].

I think the agencies of the federal government that are responsible for land management and homeland security are working together quite well. The Park Service has responsibility not just for border lands but also iconic places like the Statue of Liberty and the Washington Monument and we work with Homeland Security, shoulder to shoulder, on providing the public an opportunity to visit these sites as well as to provide security for them at the same time.

I think we have to recognize that these borderlands are important wildlife habitat. They are important for conservation in general. They are important for visitors and tourism.

I worked on the U.S.-Canadian border at North Cascades and we had great relationships with our Canadian counterparts as well as with the U.S. Border Patrol on those borders. I was recently down along the border both at Big Bend National Park and at Organ Pipe and Tahona Odom Tohono O’odham the Cabeza Prieta areas of the U.S.-Mexican border. Post 9/11 obviously there was a greater emphasis on border security and we’ve worked out many of those details. The Park Service law enforcement rangers have extraordinary expertise in backcountry patrol and how to do that kind of work and have actually worked with and helped train Border Patrol so that they could help them achieve their objectives and ours at the same time.