32 YEARS AGO this summer, my pal, the crime novelist Jim Crumley, his overeducated farmer friend from Arkansas, Harold McDuffy, and yours truly hiked six miles to Bowman Lake in Glacier National Park. For someone who had spent most of his life in the desert country of southeastern Oregon, this was a breakthrough for me. In high school I’d been driven through Crater Lake National Park in a bus, but that hadn’t seemed so much like visiting a park as the sort of thing they just did to you in high school. Crumley and McDuffy and I spent a few days loafing and fishing. I killed a fool hen with a rock. We cooked it that first night. Then we got into our only bottle of whiskey and drank the whole damned thing. The next day we solaced our hangovers on a raft of downed timber strapped together with a set of suspenders, drifting and casting to shallows in a frenzy, catching more fish than we could eat. Which was fine, because some fellows camped down the shore had brought no food whatsoever. We traded them fish for what are best called smoking materials, and quickly got over our fear of spook grizzlies in the midnight darkness. We sang to them: “Why don’t you love me like you used to do?” The grizzlies didn’t respond.

Your Official National Parks Pass

From Acadia to Zion, 70 surefire ways to climb, kayak, trek, dive, sail, fly-cast, and generally bliss out in the backcountry heaven of Glacier National Park

Glacier National Park One afternoon I found myself with my eyes closed, feathering my fingers along the trunk of a great yellow pine, encountering platelets of bark, each unique and yet not unlike all the others. I was trying to imagine what that tree would mean to a blind person. That night, when the lake was still and mirroring silver under the full perfect moon, loons called and called, and I thought they were singing to me. It was one of those times when I found out that the world had more to it than I’d imagined, more pleasure, and more glory. And all because we’d chanced a few days of frivolity, play, and release.

Sure, there was that rapacious fishing. But I’m willing to excuse us; that was another world and we were rednecks on vacation. At least we weren’t trying to skip snowmobiles across the lake.

America the beautiful, the “fresh green breast of the new world,” according to F. Scott Fitzgerald, is about freshness and greenness as metaphors for life and health, a new-by-God-world that might stay sort of new and fair if we take care of it. Our national identity is embodied in liberties and natural wonders, freedoms, and the kinds of places we choose to celebrate in our parks—mountains, great swamps, canyonlands—all open and receptive spiritual playgrounds. That identity is threatened by each instance of environmental heedlessness, each clear-cut, each ill-sited power plant and oil drill, each extinction and political sellout. We need to understand that we are responsible for ourselves, for one another, and for the well-being of the natural world, which sustains us.

How to react? Go float down the Grand Canyon. Stop at Matkatamiba Rapids, and walk into the side canyon, which opens into walls of cream- and honey-colored limestone. Sit quietly, soaking in the infinities. Once I saw a wolverine on a lakeside sandbar in Glacier; it was there, then aware of me, and vanished, and was thrilling in its wildness. Yes, go visit the parks. Then come home refreshed, revitalized, and ready to save them.

Glacier

A Hiker’s Valhalla in Montana

Your Official National Parks Pass

From Acadia to Zion, 70 surefire ways to climb, kayak, trek, dive, sail, fly-cast, and generally bliss out in the backcountry heaven of Glacier National Park

Glacier National ParkEstablished 1910

1,013,572 Acres

COMBINED WITH WATERTON LAKES, its sister park just across Canada’s border, Glacier offers more than 700 miles of foot trails, 48 glaciers, 1,600-odd miles of river and stream, 650 lakes, soaring peaks, hanging valleys, meadows spattered with wildflowers, thick evergreen forests, and several species that outrank you on the food chain. In short, it’s a theme park for BACKPACKING. To find a chunk of backcountry all to yourself, the three-night, 20-mile Gunsight Pass Trail can’t be beat. You’ll trek through the guts of the park’s wilderness—one of North America’s largest intact ecosystems—with killer mountain-and-lake ambience, a Continental Divide crossing, probable sightings of mountain goats, and possible encounters with grizzlies (be prepared). Leave your car at Lake McDonald on Glacier’s west side, and take a park shuttle on 52-mile Going-to-the-Sun Road to Jackson Glacier Overlook, east of the Divide. Hike downvalley and then up from there, passing avalanche slopes and two glaciers, 6.2 miles along a drainage to Gunsight Lake, where you’ll pitch a tent and bask in celestial views of Mount Jackson and Fusillade Mountain. Day two calls for a challenging five-mile leg over the Divide at 6,946-foot Gunsight Pass to Lake Ellen Wilson; up top, take time to poke around the old rock shelter, the only one remaining atop Glacier’s passes. Day three is a short haul, “but the longest 2.7 miles in the park,” says Glacier wilderness manager Kyle Johnson: a 1,120-foot gain to Lincoln Pass, followed by a 450-foot drop into Sperry Basin. Take your pick here: Pitch a tent at Sperry campground, or upgrade to a fairly pricey bunk nearby at the 1912 Sperry Chalet ($150 for the first person, $100 for each additional person, meals included; 888-345-2649, ). Day four: six miles down, out of the subalpine zone, and into a forest of spruce, cedar, and hemlock to Lake McDonald.

WHEN TO GO: Many backcountry campsites, like Sperry, can’t be advance-booked until August 1, when summer (all five weeks of it) reaches the park. But if the snow clears early, walk-ins can sometimes score a coveted berth in July. Pre-snowmelt in the high country, you need crampons, an ice ax, and glacier know-how so you don’t Enron off a sheer drop-off into the abyss.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 1.73 million. (High: August, 487,800. Low: December, 3,387.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: RAFT the untamed, bouldery Middle Fork of the Flathead or the slightly more subdued North Fork (each Class II-IV), tinted emerald by glacial silt; BIKE Going-to-the-Sun by moonlight (east-to-west is the somewhat kinder direction).

HEADLAMP READING: Along the Trail: A Photographic Essay of Glacier National Park and the Northern Rocky Mountains, by Danny On and David Sumner; Man in Glacier, by C.W. Buchholtz

LOCAL SPECIALTY: Stop for huckleberry ice cream and Flathead cherries at any of the roadside stores on the way to the park. And the Park Cafe in St. Mary, Montana, makes ice cream and berry pies someone should write a song about.

INSIDE SCOOP: Need some incentive to brush up on bear etiquette? How about this: Since the park’s establishment, grizzlies have killed ten people within its boundaries.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 406-888-7800,

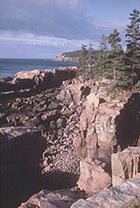

Acadia

A Seal’s-Eye View of the Maine Coast

Acadia National Park

Acadia National ParkEstablished 1919

47,498 Acres

NEW ENGLAND’S ONLY NATIONAL PARK, Acadia manages to shoehorn some 2.8 million annual visitors into its compact landscape, the bulk of it on Mount Desert Island (with smaller tracts on Isle au Haut and nearby Schoodic Peninsula). The finest way to lose the crowds and take in the park’s cymbal-crash surf, craggy stone-shored islets, and requisite cliff-top lighthouses is to venture out of bounds SEA KAYAKING. Because Mount Desert Island isn’t particularly well situated as a launching point for overnight paddle trips—the closest campable public islands are a daunting six to eight miles of open-ocean slogging to the east or southwest—day trips are more inviting. Put in at the public boat ramp in Manset, near the island’s southern end, and mosey up Somes Sound, the Lower 48’s only bona fide fjord, for a laid-back five-hour voyage through the Maine that sets watercolorists’ hearts aflutter. Watch for porpoises, seals, and cliffs more than 400 feet high (and do yourself a favor, Cap’n: Time it so you’re paddling in and out of Somes with the tides). Another day’s ramble begins at Seal Harbor’s beach and aims south for the Cranberry Islands; Little Cranberry, with the Islesford Historical Museum and decent seafood at Islesford Dock, is a fine spot to stretch your sea legs. The most reliable marine-mammal ogling goes down in Frenchman Bay, off Bar Harbor, where you can paddle among Bar Island and the magnificent and uninhabited Porcupine Islands. Keep a polite distance from seal ledges, please. Conditions in these parts can include 50-degree water, 10- to 12-foot tides, persistent fog, and wicked currents; unless you’re adept at wet exits, hire a guide. For group trips and boat rentals, contact Acadia Bike and Coastal Kayaking Tours (207-288-8118) or Aquaterra ���ϳԹ���s (207-288-0007). The Inn at Bay Ledge, perched atop an 80-foot cliff overlooking Frenchman Bay, is a most civilized base camp ($160 and up, in season; 207-288-4204, ).

WHEN TO GO: In the spring, the birds are nesting, seals are pupping, and the July 4th through Labor Day crowds haven’t arrived.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 2.8 million. (High: August, 630,240. Low: January, 18,090.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: Also on Mount Desert, MOUNTAIN BIKE the 40-odd miles of crushed-stone carriage roads, originally laid out by one John D. Rockefeller Jr., over stone-arched bridges and into the park’s aspen- and birch-packed interior.

HEADLAMP READING: The Sea Kayaker’s Guide to Mount Desert Island, by Jennifer Alisa Paigen; Discover Acadia National Park: A Guide to the Best Hiking, Biking, and Paddling, by Jerry and Marcy Monkman

LOCAL SPECIALTY: Don’t miss tea and popovers on the lawn at the park’s Jordan Pond House restaurant on Mount Desert Island, blueberry daiquiris at Poor Boy’s Gourmet in Bar Harbor, and lobster (of course) at Thurston’s in Bernard on the western “quiet side” of Mount Desert.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 207-288-3338,

Canyonlands

High-Desert Surf ‘n’ Turf in Utah

Exploring Canyonlands National Park

Exploring Canyonlands National ParkEstablished 1964

337,598 Acres

RENAISSANCE FUNHOGS, BRACE YOURSELVES: This new trip, combining three days of MOUNTAIN BIKING with five or six days of Colorado River WHITEWATER RAFTING, may be the tastiest pairing since chocolate and cabernet. It takes you straight into the heart of the park’s high-desert rock garden, defined by the goosenecking canyons of the Green and Colorado Rivers and an almost hallucinogenic symphony of spires, buttes, mesas, hoodoos, fins, arches, and slickrock. Phase One: a two-wheeled thrill ride on most of the 102-mile White Rim Road, a celebrated track that requires a four-wheel-drive support vehicle to tote food and gear (plan this leg yourself or through an outfitter). Aim counterclockwise, along the Green River in the Island in the Sky District. You’ll encounter funky sandstone formations, bottoms with swimmable holes along the river, Viewmaster overlooks of towering spires and the La Sal and Abajo Mountains, and a quad-burning hogback climb. Eventually you turn north to trace the Colorado, heading upstream, but instead of finishing the loop take a side trail at either Lathrop Canyon or Potash to your prearranged meeting with your rafting guides. Here either your cycling outfitter or your designated driver takes the bikes and bids adieu, and you embark on Phase Two: epic Southwest whitewater. A few miles below the confluence of the Green and the Colorado roars Cataract Canyon, a chain of 28 Class III-V rapids that some claim trump those in the Grand Canyon, at least in the high-water months of May and June. Sandbar camping (when the water is low enough) and side hikes into the Maze add frosting to an already savory cake. O.A.R.S. Canyonlands guides the raft trips ($1,176 for five days, $1,256 for six, return flight from Lake Powell included; 800-342-5938, ) and can link you up with a cycling outfitter. Book way ahead, especially if you plan your own cycling trip; White Rim campsite reservations are tightly limited.

WHEN TO GO: Midsummer’s desert heat eats cyclists alive, so the shoulder seasons earn raves. April brings wildflowers, cactus blooms, and rising water on the rivers; May and June bring the most bodacious whitewater; early fall brings sighs of deep contentment.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 401,558. (High: May, 55,109. Low: January, 4,110.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: Visiting Canyonlands without taking a HIKE ought to be a felony. Island in the Sky has plenty of short day loops with jackpot views; the Needles has lots of routes on slickrock, such as the Druid Arch Trail. Enter the remote Maze District for a double shot of Ed Abbey and Butch Cassidy backcountry—no pavement, no plumbing, no such thing as packing too much water.

HEADLAMP READING: Hiking, Biking, and Exploring Canyonlands National Park and Vicinity, by Michael Kelsey; Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West, by Wallace Stegner

LOCAL SPECIALTY: Head to Miguel’s Baja Grill on Main Street in Moab for tasty fish or lamb tacos.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 435-259-7164,

Yellowstone

Running with the Pack in Wyoming

Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National ParkEstablished 1872

2,219,791 Acres

CONSIDERING ALL THE PUBLICITY and controversy that raged when wildlife biologists reintroduced gray wolves into Yellowstone in 1995 after their 60-year absence, it’s surprising how few park visitors actually venture out to see the newcomers. But that’s lucky for you, because the Lamar Valley, one of the best venues for WOLF TRACKING, is in the park’s lightly trafficked northeastern section, far from such perennial crowd magnets as Old Faithful, Yellowstone Lake, and Mammoth Hot Springs. You can certainly head out to the huge open meadows alone, but the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance offers an upgrade worth pondering. Three times a year, the Alliance runs four-day wildlife-tracking trips in Lamar (February and autumn trips focus on the valley’s resident Druid Pack, and the April/May trip on both wolves and grizzlies, which emerge from their dens around then). Trips are led by Franz Camenzind, the group’s executive director, who is also a wildlife biologist, a cinematographer, and an expert on Canis lupus—now more than 200 strong in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. The valley’s flat terrain lies between 7,000 and 8,000 feet, with three to four feet of snow cover likely from November to April, so trackers head in on either snowshoes or cross-country skis (except in early fall, when they trek in). With spotting scopes and binoculars, the chances of seeing wolves playing, loping, hunting, and post-kill gorging on up to 30 pounds of elk meat (per wolf, gulp) are excellent, especially around dawn and dusk. Groups usually stay in rustic cabins at the Yellowstone Institute, a science-education facility, attend afternoon classes in winter ecology or the like, and indulge in a celebratory soak at Chico Hot Springs before returning to Jackson Hole ($450 per person; JHCA, 307-733-9417).

WHEN TO GO: In October, bugling elk outnumber RVs, making it a copacetic time to check out even the most popular hot springs and geysers.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 2.84 million. (High: July, 768,040. Low: November, 13,422.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: With 100 miles of shoreline and nearly 150 square miles of surface, Yellowstone Lake’s chilly, crystalline waters invite unforgettable multiday SEA KAYAK jaunts. Several outfitters offer guided trips and lessons, among them Jackson Hole Kayak School (800-733-2471, ).

HEADLAMP READING: Hiking Yellowstone National Park, by Bill Schneider; The Wolves of Yellowstone, by Michael Phillips and Douglas Smith

LOCAL SPECIALTY: Eisenhower was president when Helen Gould began serving her crowd-pleasing Hateful Hamburger at Helen’s Corral Drive-In in Gardiner, Montana, at the park’s northern entrance. Forty-two years later, Helen is still behind the counter, serving up burgers, fries, malts, and tales of times gone by.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 307-344-7381,

Olympic

Washington’s Coolest Rainforest

The thick foliage of Olympic National Park

The thick foliage of Olympic National ParkEstablished 1938

922,651 Acres

FEW NATIONAL PARKS make picking your poison so gut-wrenching: Should you light out for the 7,000-foot-and-higher peaks, glaciers, and sparkling lakes of the Olympic Peninsula’s interior? The rugged headlands and tidepools of the 57-mile Coastal Strip, the longest ribbon of primitive coastline in the Lower 48? Or the moist air, gushing cascades, and brooding old growth of the temperate rainforest? Tough call, but this should help: For a gratifying combo of remoteness, adventure, and greenery so lush you’d almost swear you can hear the plants breathing, set aside three or four days to BACKPACK a portion of the 31-mile out-and-back Queets River Trail, in the park’s southwestern spur. To reach the trailhead, coax your jalopy 45 minutes or so from mile marker 144 on U.S. 101 along a one-lane gravel washboard, and then strap on your Tevas to ford two rivers, the shallow Sams and the trickier Queets, one of 13 major streams that drain the Olympic Mountains. (Though the distance isn’t long, take caution crossing the Queets; the riverbed is rocky, uneven, and slimy in spots.) From the far bank, mostly level trail meanders through a wonderland that contains about as much biomass as anywhere on earth: hypertrophic Sitka spruces, Douglas firs, hemlocks, red cedars draped with epiphytes, and ferny undergrowth. Plus you’ll find riverside sandbars inviting quick dunks in the martini-cold Queets and many a well-situated tent site. Elk herds have been known to make a cameo. Words to the wise: Pay close attention the last three miles before the trail turn-around, because the path is easily lost here; rainfall during your journey could swell the river and strand you on the wrong side; and bear-resistant food canisters are yours to borrow from any ranger station ($3 suggested donation).

WHEN TO GO: After Labor Day, when summer crowds have ebbed and the weather’s still relatively unsoggy.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 4.18 million. (High: August, 732,335. Low: January, 158,250.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: Take a full-moon HIKE in the mostly treeless Obstruction Peak area off winding Hurricane Ridge Road (if you luck into clear skies); SOAK yourself at Sol Duc Hot Springs in the park’s northern quarters.

HEADLAMP READING:Olympic Mountains Trail Guide: National Park and National Forest, by Robert L. Wood; Cascade-Olympic Natural History, by Daniel Mathews

LOCAL SPECIALTY: Many a hiker has replenished his lipids with a greasy burger and a blackberry shake at Granny’s Cafe, on U.S. 101 between Port Angeles and Lake Crescent.

INSIDE SCOOP: As national-park corpse stories go, it’s hard to top this one: In 1937, a local waitress named Hallie Illingsworth vanished unaccountably. Three years later, two fishermen on Lake Crescent, a 600-foot-deep glacial reservoir along the park’s northern boundary, discovered her floating body. It had risen from the lake’s sunless bottom, where in the 44-degree water it had saponified—changed to the consistency, as eyewitnesses put it, of Ivory soap. Shortly thereafter, her third husband was convicted of her murder.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 360-565-3130,

Theodore Roosevelt

Rough Riding North Dakota’s Badlands

Theodore Roosevelt National Park

Theodore Roosevelt National ParkEstablished 1947

70,447 Acres

“A DESOLATE, GRIM BEAUTY,” said this park’s namesake, who hunted bison and dabbled in cattle ranching on its stark rolling prairies and broken badlands in the 1880s. Most visitors sample the park from their cars via scenic drives in one of its two units—North and South, separated by 45 miles as the eagle flies; a hardy minority brave the Easy-Bake summer climate to hike the park’s long looping trails. The most tantalizing local adventure, however, lies mostly outside park boundaries: MOUNTAIN BIKING the Maah Daah Hey Trail, 96 unpaved and remote miles that connect the two park units not far from the Montana border. Fat-tire junkies are already calling the trail, completed just three years ago, “the new Moab.” Heady stuff, but consider the evidence: the nation’s longest uninterrupted bikeable track, with some surprisingly demanding stretches, winding through buttes, canyons scooped out by the Little Missouri River and its feeder streams, rain-sculpted hoodoos, steep ravines, sagebrush valleys, thick stands of cottonwood and juniper, dry riverbeds and wet ones too. Four backcountry campgrounds spread out along the way either have potable-water wells, or will by sometime this summer, so you can make yourself at home where the buffalo really do roam (antelope, wild horses, and rattlesnakes, too). Bikes aren’t allowed within national park boundaries, so a spur trail out of Sully Creek State Park does an end-around to the west to skirt the South Unit. Take care not to spook the hikers and equestrians you’ll occasionally encounter along the Maah Daah Hey (a Mandan Indian term meaning either “grandfather” or “be here long”). Factoring in the heat, through-cyclers should allow at least five days to complete the trail, though backroads access also allows for a variety of sampler day rides; be forewarned that rain transforms the trail’s surface clay into a nasty, slick gumbo. Whichever direction you ride, arrange for a shuttle pickup to get back to your car through Badlands Guide Service (701-225-6109) or Little Knife Outfitters (800-438-6905), which also rents bikes.

WHEN TO GO: Spring rains generally taper off after mid-June. If you can wait, a killing frost usually arrives by September 10 or so, cooling the daytime swelter, zotzing mosquitoes, and triggering the onset of fall colors.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 438,391. (High: July, 117,191. Low: December, 1,210.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: If the river’s high enough, CANOE the Little Missouri through both sections of the park and the grasslands between—110 miles of drifting through high banks, casting for catfish, camping in cottonwood groves, and occasionally walking your boat through rocky shallows. Paddlers often put in at Medora and finish up at U.S. 85 near the North Unit. River conditions are usually best mid-May to mid-June; check water levels on the Web at (click on the Current Streamflow Conditions link).

HEADLAMP READING: Exploring the Black Hills and Badlands: A Guide for Hikers, Cross-Country Skiers, and Mountain Bikers, by Hiram Rogers; Theodore Roosevelt National Park: The Story Behind the Scenery, by Bruce M. Kaye and Henry A. Schoch

LOCAL SPECIALTY: If all that meat on the hoof gets your mouth watering, the Iron Horse Saloon and Restaurant in Medora grills up a mean buffalo steak.

INSIDE SCOOP: Cyclists should Slime their tires and bring a patch kit and at least two spare tubes. The Maah Daah Hey’s prickly-pear cacti and sharp rocks bite—and so will your ride if you aren’t prepared for flats.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 701-623-4466, . (For Maah Daah Hey trail information, see the Dakota Prairie Grasslands Web page at , or .)

Virgin Islands

Caribbean Windjamming

The coast of St. John’s, Virgin Islands National Park

The coast of St. John’s, Virgin Islands National ParkEstablished 1956

28,582 Acres

WITH ABOUT 60 PERCENT of its lush green hills and white crescent beaches set aside as national park, the island of St. John isn’t all that different from what Columbus saw when he claimed these islands for Spain. All things considered, it’s still the virgin Virgin. But with increasing numbers of day-tripping cruise-ship passengers catching the ferry over from St. Thomas, you need to pick your spots a little more carefully these days. In short, you need to charter a boat and go SAILING. Cruise among secret coves, secluded anchorages, 40 beaches, and the reefs that ring St. John (many of them within park boundaries) for ten days or more without exhausting the idyllic possibilities. Hawksnest Bay is a locals’ favorite, with three gorgeous beaches, where incurable Type A’s can usually find that day’s New York Times at nearby Caneel Bay Resort by midafternoon. Leinster Bay’s Waterlemon Cay is a blissful spot for ogling corals, starfish, parrot fish, sergeant majors, spiny lobsters, octopuses, and intriguingly ugly scorpion fish. Along the south shore, Salt Pond Bay offers more great snorkeling and a sheltered mooring, and from there you can catch the switchbacking trail for a mile through agaves and cacti up to Ram’s Head, a prime vantage for winter whale-watching. Since no water-skiers or jet skis are allowed in park waters, the only “noise” you’ll hear at sunset is the gentle slap of wave on hull and, presumably, the clinking of glasses. For crewed charters, contact Yates Yachts (866- 994-7245, ), the Virgin Island Charter Yacht League (800-524-2061, ), or Island Yachts (340-775-6666, ), which can also arrange bareboat charters. Prices vary widely, but figure about $1,300-$1,400 per person per week for a crewed boat (based on a group of six or so); bareboat charters start around $1,700-$2,500, depending on the season.

WHEN TO GO: For fewer visitors and lower off-season rates, find the gaps on the calendar between winter’s peak crowds and August-to-October’s hurricane season—namely, May through July and November to mid-December.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 703,992. (High: March and April, both about 82,600. Low: September, 26,134.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: None of the park’s 22 HIKING trails is longer than a couple of miles, but all lead to extremely pleasant diversions: ruins of Danish colonial sugar mills and plantations, petroglyphs, aromatic tropical forests, and views of Tortola and the rest of the British Virgin Islands.

HEADLAMP READING: A Natural History Atlas to the Cays of the U.S. Virgin Islands, by Arthur Dammann and David Nellis; Lonely Planet’s Diving & Snorkeling the British Virgin Islands

LOCAL SPECIALTY: At Skinny Legs, a beach-shack hangout in Coral Bay on the island’s east side, you can enjoy a proverbial cheeseburger in paradise and a Blackbeard Ale while mingling with the yachties who stop in after picking up their mail next door.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 340-776-6201,

Isle Royale

Michigan’s Superior Beneath the Surface

Isle Royale National Park

Isle Royale National ParkEstablished 1940

571,790 Acres

KAYAKERS COME to this roadless, carless Lake Superior island for its rocky shoreline; fishermen and canoeists, for its 22 inland lakes; backpackers, for its wooded basaltic ridges populated by moose and timber wolves; and hermits, because in its entire season Isle Royale sees 40,000 fewer humans than Great Smoky Mountains gets on an average July day. A savvy and intrepid handful of park trailblazers know how to really get lost here: Venture below the lake’s forbidding surface for SHIPWRECK DIVING. Ten major vessels have come to rest in park waters in the last 125 years, and the same frigid 40-degree water that forces divers to don drysuits has drastically slowed the wrecks’ decomposition. Visibility is so good you can survey a ship’s exterior 40 feet down without a light. The shallower remains are most popular, such as theAmerica, a package freighter that sank in 1928 and whose bow lies just a few feet below the surface. Others sit farther down; the Kamloops, a Canadian freighter that took 50 years to locate after it succumbed to a blizzard in 1927, lies between 175 and 260 feet under. Most divers join one of two Park Service-sanctioned dive-charter operators—Superior Trips (651-635-6438, ) and RLT Divers Inc. (507-238-4671, )—and spend a week diving and camping in any of the park’s 36 designated campgrounds. Isle Royale is only open mid-April through October; ferry rides from Grand Portage, Minnesota, or Michigan’s Upper Peninsula take three to seven hours.

WHEN TO GO: The number of visitors—as well as blackflies and mosquitoes—subsides in the shoulder seasons, before June and after August, if you don’t mind risking more fickle weather and rougher chop on Lake Superior.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 15,180. (High: August, 5,664. Low: October, 112.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: HIKE a portion of the 165-mile network of trails, such as the 42-mile Greenstone Ridge or the rougher 29-mile Minong Ridge. Each traverses the island from northeast, over steep bedrock ridges, to southwest, where you’ll find thick forests of birch, maple, and other northern hardwoods. The Minong’s marshy wetlands are prime moose turf in the summer. Come nightfall, listen for the spine-tingling sound of wolves howling.

HEADLAMP READING: Shipwrecks of Isle Royale National Park: The Archaeological Survey, by Daniel Lenihan, et al.; Isle Royale National Park: Foot Trails and Water Routes, by Jim DuFresne

LOCAL SPECIALTY: At the Harbor Haus in Copper Harbor, Michigan, the picture windows overlook Lake Superior, the walls are adorned with deerskins and beer steins, the German-leaning kitchen serves up lake-caught whitefish, venison sausage, and desserts made with local thimbleberries, and the table-waiting frauleins duck out onto the back patio for a Rockette-style kick line to greet the ferry returning from Isle Royale.

INSIDE SCOOP: The park is a remarkable case study of the peculiar cycles of island biogeography. In the mid-19th century, it harbored populations of caribou, coyotes, chipmunks, and redbacked voles—none of which exist there now—but not a single moose or wolf. Prevailing speculation suggests that the moose swam over around 1900, and that wolves arrived in the winter of 1949-1950, the last time ice formed an unbroken bridge to the mainland.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 906-482-0984,

Rocky Mountain

Hugged a Colorado Fourteener Lately?

Falls River, Rocky Mountain National Park

Falls River, Rocky Mountain National ParkEstablished 1915

265,769 Acres

JUST AN HOUR AND A HALF’S DRIVE from Denver and less than an hour from Boulder, Rocky Mountain National Park draws legions of Front Range residents with its elk meadows, hikes to chilly alpine lakes, and Trail Ridge Road, its Divide-straddling highway. Less appreciated is that when it comes to CLIMBING, the park’s got something for every subculture: alpine routes, sport climbs, bouldering, ice climbs, ski-mountaineering tours. At 14,255 feet, Longs Peak is “the granddaddy of them all,” says Jim Detterline, a ranger who’s summited Longs 186 times and counting. Perhaps as many as 20,000 other people also reach the top each year, most of them by the Keyhole Route (the only way to hike to the top) and most of them in August. Very few brave the Stettner’s Ledges route on the mountain’s East Face. Their loss. Rich with alpine history, the climb, rated a Grade III 5.8, was first ascended in 1927 by a pair of German-American brothers from Illinois; at the time, it was among the continent’s toughest routes, and it’s still no gimme, even for those acclimatized to high altitude and up to the task. Stettner’s entails a pre-climb backcountry bivouac, a glacier crossing, and ten pitches (the last four on the Kiener route) over fractured granite, chimneys, cracks, ledges, and past rows of rusting pitons from generations ago, all capped by a 600-foot scramble over scree to the top. Typically, this means six to eight hours of heroics after a 5 or 6 a.m. start to avoid afternoon lightning. But you’ll still want to pause to catch your breath and take in your surroundings, which include a close-up view of the Diamond, a 1,200-foot-tall face that Detterline likens to a Yosemite-style big wall, only with high altitude thrown in for good measure. Those who prefer to start on a slightly smaller scale can contact the Colorado Mountain School in Estes Park (970-586-5758) about lessons and guided climbs.

WHEN TO GO: The last two weeks in October are a good bet—winter hasn’t yet arrived, and most tourists have departed.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 3.4 million. (High: July, 774,781. Low: January, 79,126.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: The elk put on a blockbuster show from late August to early October, when bulls battle for mates and eerie bugling echoes through the meadows. Catch the performances sans the mob in the Arapahoe Meadows and Lily Lake areas.

HEADLAMP READING: Rocky Mountain National Park Climber’s Guide: High Peaks, by Bernard Gillet; Rocky Mountain National Park Natural History Handbook, by John C. Emerick

LOCAL SPECIALTY: If you’re really determined to go native, drop in at the Buckhorn Exchange, Denver’s oldest restaurant, for the Rocky Mountain oysters (translation: fried bull testicles).

INSIDE SCOOP: Rumor has it that stashed away in a file at park headquarters, there remains a sheet of butcher paper on which a pair of hikers years ago sketched an outline of a five-toed, 24-inch-long, humanlike footprint they found in the mud in a seldom-visited area of the park—evidence, some allege, of Rocky Mountain’s very own Bigfoot.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 970-586-1206,

Lake Clark

Untamed Alaska, and Lots of it

Twin Lakes, Lake Clark National Park

Twin Lakes, Lake Clark National ParkIF YOU’RE LIKE ALMOST EVERYONE else on earth, you’ve managed to overlook Alaska’s Lake Clark National Park and Preserve and its four million acres of stunning alpine and tundra wilderness. Ranger Dennis Knuckles sums up the amenities in this roadless domain nicely: “There’s no 911, no cell-phone structure, and nobody saving your bacon.” If remote and unforgiving terrain and capricious weather appeal to you, this huge tract on Cook Inlet 150 miles southwest of Anchorage won’t disappoint. Visitors are few and natural spectacles plentiful: the jagged 6,000-foot Chigmit Mountains, three National Wild and Scenic Rivers, glacier-gouged lakes and valleys, boreal forests, and even two active volcanoes. A FLY-IN BACKPACKING trip is the best way to see a portion of the park’s vast western interior. Have a floatplane deposit you above tree line at the shores of Turquoise Lake, whose milky aquamarine surface reflects the surrounding mountains (if you get dropped at the south shore, you can avoid a potentially hairy crossing of the Mulchatna River). Pitch your tent anywhere you like and stash your watch deep in your pack—you won’t be needing it. You’ve got seven days (or whatever you and your bush pilot agree upon) to downshift. Explore the shrubless tundra. Hike to a living glacier. Wake to thousands of caribou outside your tent. Commune with moose and Dall sheep. See no humans. Gradually meander ten to 12 miles south to the north shore of Lower Twin Lake, the vegetation slowly shifting from tundra to scrub to black spruce and dwarf birch. If you wouldn’t mind a little hand-holding, Alaska Alpine ���ϳԹ���s guides trips here in summer and fall (877-525-2577; ). For air-taxi information, go to .

WHEN TO GO: Late June and early July promise a decent chance of sunshine and close encounters with the Mulchatna caribou herd, some 200,000 strong, plus 19 hours of daylight; for the warm-blooded, March is great for epic winter camping and cross-country skiing around the lakes.

ANNUAL VISITORS: All of 4,397 (High: June, 954. Lows: November through April, all tied at about 150.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: RAFT or KAYAK the Tlikakila, the only river that flows entirely within park boundaries. It runs swift and shallow, slicing by forests of spruce, aspen, and birch, snowcapped peaks, waterfalls, and sheer cliffs. Three- to four-day trips from Summit Lake usually run about 45 miles; if you choose to float without a guide, have your pilot take a pass over the river beforehand to scout for logjams. Go to for a list of kayaking and rafting guides who serve the area.

HEADLAMP READING: Looking for Alaska, by Peter Jenkins; One Man’s Wilderness, by Richard Proenneke and Sam Keith

LOCAL SPECIALTY: Cast into Lower Twin Lake for grayling or lake trout. Both take well to a dry fly and (shortly thereafter) a little butter and cornmeal.

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 907-781-2218,

Great Smoky Mountains

The Southeast’s Backwoods at its Best

Morning mist settles along Great Smoky National Park

Morning mist settles along Great Smoky National ParkEstablished 1934

521,490 Acres

IN THE SMOKIES, the numbers tell good news and bad: 930 miles of trails, almost 500 miles of fishable streams, hazy blue ridges topping out above 6,000 feet (the highest east of the Rockies), 4,000 species of plants, 65 of mammals…and upwards of nine million humans every year. So head where the masses aren’t—the Greenbrier area, across the North Carolina border on the Tennessee side—for three sweet and soothing days of HIKING and FLY-FISHING. Start hoofing it at the Porter’s Creek trailhead, reached by entering the park off Highway 321 east of Gatlinburg. Follow the wide creek for five miles until you reach the evocatively named Campsite 31, gaining about 2,000 feet of elevation in the process—good reason to stop and wet a line. Casting is easier here than in many of the park’s cramped, brush-banked streams, and you can catch browns, rainbows, speckleds, and brookies (throw back the latter; they’re the only natives). Legend has it one ranger landed a 21-inch trout in Porter’s, so come prepared. Next morning, backtrack a couple miles from your campsite to the Brushy Mountain Trail, where you’ll cross more trout streams and roam through tulip poplars, hemlocks, rhododendrons, and mountain laurels. Bunk that night at the Mount LeConte shelter, a three-sided stone structure at 6,593 feet (free; reserve through the backcountry office at 865-436-1297). Or book a slot at the LeConte Lodge, a rustic haven reachable only by trail and lit by kerosene lamps (cabins and group lodges start at $81.50 per adult per night; call 865-429-5704). On the third day, march six more miles on the Boulevard Trail, encountering many a heart-stopping mountain vista, to another shelter, at Icewater Springs near the Appalachian Trail (70 miles of which traverse the park). Finally, a two-mile taste of the AT takes you to Newfound Gap Road, where you thoughtfully arranged for a shuttle to pick you up ($44, A Walk in the Woods, 865-436-8283).

WHEN TO GO: Early spring before school’s out, and September after Labor Day. Flower fans, mark your calendar accordingly: April brings ground flowers; May, mountain laurel; June, rhododendron. Yes, the fall leaves are pretty, but skip October—that’s the park’s second-busiest month.

ANNUAL VISITORS: 9,196,408. (High: July, 1.4 million. Low: January, 297,855.)

MORE CHOICE ADVENTURE: Treat yourself and your MOUNTAIN BIKE to eight-mile Round Bottom Road and its lightly traveled curves. You’ll find it on the North Carolina side in the park’s southeast end.

HEADLAMP READING: Great Smoky Mountains National Park, by Rose Houk, photographs by Michael Collier; The Wild East: A Biography of the Great Smoky Mountains, by Margaret Brown

LOCAL SPECIALTY: The Old Mill, in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, serves up heaping helpings of southern Appalachia: rocking chairs on the porch, bluegrass on weekends, and more fried chicken than you can finish. Drop in early to avoid lines.

INSIDE SCOOP: Stock these trout flies in your arsenal, and your odds of getting skunked diminish greatly: Smoky Mountain thunderhead, Coffey’s stonefly, blue-winged olive, yallerhammer, Palmer fly, and Adams variant. Hunter Banks, a fine fly shop in Asheville, North Carolina, offers gear and advice (800-227-6732; ).

PARK HEADQUARTERS: 865-436-1200,