In May 2007, Steven Kotler and his wife, Joy Nicholson, moved from Los Angeles to Chimayo, New Mexico, to open a dog-rescue operation that they named Rancho de Chihuahua.

Animal Rescue

Annie Marie Musselman

Annie Marie MusselmanAnimal Rescue

Dogs at Rancho de Chihuahua

Dogs at Rancho de ChihuahuaAnimal Rescue

Joy With (from left) Bella, Sprocket, Airtel, Teddy Bear, and Misha

Joy With (from left) Bella, Sprocket, Airtel, Teddy Bear, and MishaAnimal Rescue

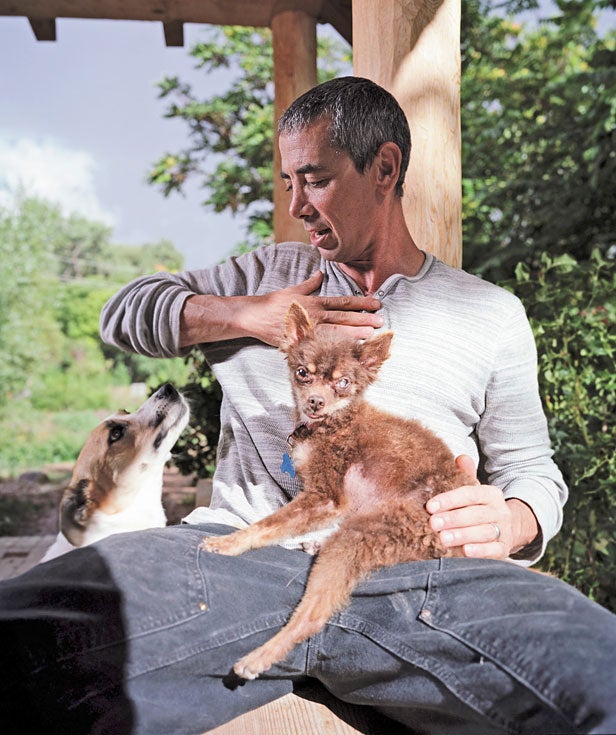

The author with Bella

The author with BellaChimayo is a tiny, rough-and-tumble town in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. It's famous for red chile, a mystical healing church, and one of the highest per-capita rates of heroin addiction in the United States. Rancho de Chihuahua is a special-needs sanctuary for dogs whose physical problems and emotional scars make them extreme long shots for adoption. Their first pack of patients was a motley assortment, consisting of a few big dogs (pit bulls, Rottweiler-husky crosses), a few medium-sizers (dachshund hybrids), and a dozen or so Chihuahuas and Chihuahua mixes. Over the months, the original collection of eight canines ballooned to north of 20.

Nicholson (a novelist who'd had years of experience in dog rescue) and Kotler (a longtime outdoor writer who didn't but was gung-ho) worked with dogs both seriously old and seriously ill, animals who needed a lot of delicate care. Delicate isn't a word often associated with Chimayo and its surrounding badlands, where their animals were attacked by bobcats, wild dogs, and, once, a murderous donkey. Still, none of them died during the first ten months, a fact that struck the couple as mildly miraculous. But in February 2008, the universe decided to make up for lost time, with a skein of dog deaths that made Kotler start to wonder if he could handle what he'd signed up for.

AT MOST COMMERCIAL breeding facilities in the U.S.ÔÇöknown as “puppy mills” in rescue slangÔÇödogs are packed into wire cages, usually for the entirety of their time there, often in pitch-black conditions. There are waste-collection trays beneath the cages, but they're rarely emptied. Flies are a constant. With no air conditioning in summer, no heat in winter, dogs regularly freeze to death or die from heatstroke. The food is bad and vet care infrequent. Open sores, tissue damage, blindness, deafness, and ulcers are more the rule than the exception.

Maus was a Chihuahua, a breeder dog, rescued from a puppy mill. For two years, dating back to our time in Los Angeles, Joy worked with her on a daily basis. It was an uphill battle. By the time we got her, Maus was mostly deaf, completely blind, and seriously damaged. Open spaces were too much for her to bear, as was the company of people (especially men), other dogs, sunshine, loud noises, and any sort of affection. Maus lived at the back of a closet and never came out. Her entire world consisted of a bed, a water dish, and a couple of pee pads.

Holding her was impossible, so Joy would scrunch under a shelf that ran along one side of the closet and stay still for an hour at a time. After six months, she got Maus to accept a scratch on the neck. After nine months, Maus allowed a head rub. But that was as far as things went. Anything else and Maus would start wailing and shaking. We tried every drug on the market and a dozen other therapies, but nothing did the trick. In the end, we realized that prolonging her suffering was the worst available option. We decided to put her down.

Maus was my first experience with an incurable case, and the timing of our decision couldn't have felt worse. Two weeks after the death of Ahab, our Rottweiler-husky mixÔÇöand a few days after an unknown someone sighted a high-power rifle over a fence and shot and killed a friend's golden retrieverÔÇöMaus was euthanized, with Vinnie alongside her.

Vinnie was an old schnauzer from L.A. whose owner had died of AIDS, so he ended up on the rescue circuit. At the time, we were babysitting a couple of young Chihuahuas for a local humane society. Since finding homes for Chihuahuas in L.A. is significantly easier than finding an old schnauzer a home just about anywhere, a trade was arranged: The Chihuahuas went to Beverly Hills; Vinnie came to New Mexico.

Vinnie seemed to love life in Chimayo. He had a stump for a tail, but that didn't stop his self-expression. Every morning he would dash outside, glance up to see the wide sky and open fields, and run big laps around our one-acre property before flying back to the porch to wag his stump. I had come to love that wag. It started at his head and ended at his butt and made him look like a freight train trying to breakdance.

About the time we decided to euthanize Maus, Vinnie's heart and liver started to fail. We made another tough choice. Forty-eight hours later, both Vinnie and Maus were put to sleep on our back porch. Maus died in Joy's arms, Vinnie in mine. He was the first living thing to die under my care, but not the last. A few days later, Chow, an adorably feisty terrier, started coughing at around six in the morning. By seven, her lungs had filled with fluid, and by eight she was gone. The following week, for reasons still unclear, we lost a dachshund named Jerry. Then Otis, our beloved bull terrier, died of a stroke three days after that. The count was seven dead in two months.

Moving to New Mexico to save dogs had been the plan. The problem now was: Who was going to save me?

AT FIRST GLANCE, a bull terrier puppy is an unlikely source of salvation. Mostly, they're an exercise in collateral damage. With their jaws and teeth and disposition, they can destroy a pair of jeans in 20 seconds. Making matters more complicated, our new bull terrier, IgorÔÇöwhom we got in June 2008 from a group called Southern California Bull Terrier RescueÔÇödidn't like small dogs. It wasn't a prey issue. He knew they were members of his species and weren't supposed to serve as dinner. But our unruly pack of ChihuahuasÔÇöthen numbering around a dozenÔÇöjust plain bugged him.

The only way to ensure peace was to exhaust Igor. In the beginning, because he wasn't used to Chimayo's altitude, a good walk did the trick. Pretty soon runs were required, and not just for Igor. On the Fourth of July that year, some local shithead wrapped his puppy in firecrackers and lit the fuse. The dog was found tearing down a highway with a skunk-stripe of singed fur and melted flesh. We got the call because the burns were going to take a while to heal, and in the animal-rescue world, time means space. We didn't really have any, but our friends at the humane society knew what kind of sucker my wife was for injured ChihuahuasÔÇöso that's how they described him to her.

This dog was no Chihuahua. He was part pit bull and part hellhoundÔÇöwith a face that was unmistakably Calvin Coolidge. He had to wear a cone until the burns healed, and, being a puppy, he quickly destroyed six of those. To create something he couldn't destroy, we cut a hole in the bottom of an old plastic bucket, so Bucket was the name that stuck. If Igor was an eight on the Richter scale, Bucket was a ten. By the middle of summer, exhausting these two went from crisis management to the only prayer we had left.

Thus began the Five-Dog Workout, though this label isn't entirely accurate. Sometimes there were five dogs, sometimes ten. At the start, the workout entailed a trail run up a fire road. But the dogs kept getting lost, so I had to switch from fire roads to arroyo bottoms, where the sides were steep enough to keep the dogs penned in.

Since snowmelt and heavy rains tended to pile up debris at various points, running the arroyos required occasionally stopping to climb over tree limbs and rusted car parts and everything else that washes downstream. Or it did until about a month into this experiment, when Igor spotted a jackrabbit and bolted. Rather than climb over a junk pile, he shot partway up the canyon wall and came down on the other side of the blockage. He looked like a snowboarder on a halfpipe.

Of course, I went right up after him. I tore up the wall, banked a turn, came back down, and then ran up the other side. It was so ridiculously fun that I forgot what I was doing and just kept going. There were seven other dogs with me that day, and they kept pace right behind us, resembling a bobsled team moving through a chute, except this team seemed to be laughing.

In the beginning, those arroyo runs were mostly about stamina; later, they required some skills. Igor soon mastered the gradual curve and moved on to the dead vertical, trying to run straight up the sides. If the sides got too steep, he'd attempt to cat-leap to the top. Like most bull terriers, he cat-leaped about as well as he performed long division. But Bella, a pit bull├óÔéČÔÇťheeler mix, could do almost anything she tried, including midair 180's. This drove Igor crazy.

Often, when Bella pulled some stunt Igor couldn't duplicate, he'd just vanish. There were days when I would call and call and he wouldn't come. One morning, I hunted around until I found him, hard at work, on a different cliff, practicing Bella's moves. He went up the wall and flew sideways, missing and smashingÔÇöhard and repeatedlyÔÇöbefore he got it right just once.

There's some elementary behavioral science that explains why Igor would want to “hide” his practice sessionsÔÇöbasically, showing signs of weakness is a great way to lose standing in the pack. But in his case, I think it was pure embarrassment. Igor was a klutz. He took some bad falls. The fact that he wanted to rehearse privately seemed perfectly reasonable.

His embarrassment faded when Bucket got hip to the cause and also started trying to run up walls. Bucket is small and squat and about as aerodynamic as a wheelbarrow. For a while, the Five-Dog Workout became the Cirque du Soleil Reject Hour. And when Igor realized he wasn't the only klutz out there, he stopped trying to hide his failures. Bella would pull some acrobatic feat and Igor and Bucket would spend the rest of the run falling all over the place, trying to learn it.

Afterwards, our runs became a giant game of follow the leader, only considerably more chaotic. When Bucket had point, he preferred the low curves of gentle arroyos; Igor, the skate park of the canyon walls. Bella went straight no matter what was in her path. I fell down a lot. The soft dirt was carvable, which meant that sharp turns were theoretically possible. Those turns were needed because the dogs ran like wolves, as a tight pack, and I wanted to keep up.

“Part of the pleasure of being around dogs is a sense that we are participating in rituals that go back to atavistic pack behavior,” Jeffrey Moussaieff wrote in his book Dogs Never Lie About Love. I agree. One day, as we were coming down a steep cliff, Igor cut me off. I tripped, he crashed, and Bella came down with us. Together we cartwheeled over a boulder and into a cactus. Pleasure was had by all.

STILTS ARRIVED IN NEW MEXICO one day in January 2009, a mixed-breed California transplant, short-haired, coat mostly black, a pinched face, long nose, wide eyes, a few teeth left, half an ear missing, all his tail, standing about two feet high, with the torso of an armadillo and the legs of a giraffe. He looked like a stilt-walking Hobbit with an eating disorder.

For any dog, meeting a new pack is the equivalent of switching high schools, so we take it slow. Big dogs meet big dogs first, small dogs meet small dogs. This was a problem for Stilts: He was significantly bigger than the small dogs, significantly smaller than the bigs.

In his recent life, Stilts had gone from person to person, shelter to shelter, state to state, and who knows what else. He needed to sleep off the shock. Two days is the norm for this process, but a month later Stilts hadn't moved much from a pillow under a table. Attention, affection, good food, great pack, general silliness, long hikes, lots of freedom and loveÔÇöthese were our standard tools, and none was working. When I took Stilts on walks, he would wander off and hide.

Ever since I'd started the Five-Dog Workout, one untried backcountry routeÔÇöa crazy-looking ridge run that dumped over a series of small drops and then a large cornice and down to a gorgeous sandstone cliffÔÇöhad grabbed my attention. Every time I walked that way, I stared at it. Was it even doable? The cliff looked too steep, the cornice drop too big. Something about it made me want to try, and something about it kept scaring me away. I suppose I was waiting for a sign.

I got one a few days before Stilts arrived. Igor, Bella, Bucket, and I were climbing a tall ridgeline just before sunrise. The route was directly across from us, still mostly in shadow. A few minutes later, we topped the ridge as dawn swept in and the whole valley lit up. And there, suddenly visible, sitting 50 feet below the cornice, was the biggest coyote I've ever seen.

He was the size of a wolf, with thick, silvery fur and paws like salad plates. He saw us immediately, but instead of running away he just stared. We stared back. Five minutes, ten minutes. Then Igor barked once. The coyote blinked and then bounded up the route in six strides, maybe seven, went over the cornice, and was gone. It was like a three-hour ballet condensed into a moment.

We ran “Coyote's Line” that day. Igor and Bella jumped the cornice without hesitation, but Bucket took one look and found another way down. I thought about going with him but knew I'd regret it later, so I jumped, too. There was some hang time in the air and a bit of a hip-check on the landing, but the soft dirt bounced me back to my feet and momentum did the rest. A few steps later, the dogs were at my side and we were bounding down the slope together, falling five feet with every step, falling deeper into each other along the way.

A few months later, I returned to Coyote's Line with the same crew, minus Igor, plus Stilts. Stilts didn't have much trouble with the ridge, but he wasn't so sure about the cornice. Once again, Bucket backed off and found another way down. Stilts tried to follow Bucket, but I put my hand on his back and spun him toward the drop. Then I stopped myself: What was I thinking? There was no way I could shove him off a cliff.

I apologized to Stilts and released him, figuring he'd follow Bucket down. To show him what he was missing, though, I let out a whoop and jumped. Bella jumped with me. Once I slid to a stop, I looked back up to check on Stilts. He was still there, still staring off the edge. At first, I thought he was frozen in terror. Then he did something I've never seen a dog do: reared up on his hind legs and kicked his front feet in the air like a stallion. He did it twice, started barking, and jumped straight off the cornice. He kept barking all the way down, into the arroyo, where, without breaking stride, he smashed into Bella and bounced into Bucket and they all rolled into a game of bitey-faceÔÇöthe first playful contact Stilts had ever had with any of our dogs.

THE LAST TIME I RAN Coyote's Line was April 2009, just shy of our three-year anniversary in Chimayo. I had decided to take the dogs to “the Thumb.” This was another destination I'd been staring at for a while, always wanting to get closer, always afraid of what I might find. Deep in the backcountry, wind and weather had shaped sandstone into a massive fist with an extended thumbÔÇöwhat's technically called a “tent rock” or “hoodoo,” but neither of those terms quite capture its size. The Thumb was colossal: 300 feet of red rock sitting atop another 200 feet of rubble.

We set out to explore it on a cold and clear Sunday morning. With me were Bella, Bucket, Igor, and Poppycock, a shepherd stray who'd showed up around Christmas and never left. We spent the first hour crossing wide plains on wide trails. By the second hour, we'd moved into a slender arroyo that narrowed into a slot canyon that soon became a maze. The exit was at the top of a steep hill, where we got our first good look at the Thumb. But no sooner did we see it than it vanished in a whiteout.

Flurries had been drifting down for a while, but suddenly it was dumping. I rounded a corner and found myself standing at the mouth of a wide arroyo just as the entire riverbed sprang to life in a whirlwind of snow. Just as quickly, the wind calmed and a great silence returned. Here was the real voice of the desert, the whisper that's always there.

We didn't listen that dayÔÇöbut we should have. Instead, we kept clomping forward, postholing through deepening drifts. It took another hour to get to the bottom of the rubble pile, and the moment we arrived, the storm abated. I stood beneath the Thumb with my neck craned back, looking at all that rock, all that deep time, a bad feeling starting to rise in my stomach. I felt like I was trespassing, violating some covenant written eons ago.

I ignored the feeling, so we kept going. The escarpment was steep and crumbly and it took five minutes to scramble to the top. As we reached the Thumb, the storm returned. Biting cold, howling wind, visibility gone. I could barely see the dogs beside me. We hunkered down to wait it out.

Usually when I rest in the backcountry, the dogs run over, give my hand a lick, and then head off exploring. That day, they didn't just lick me, they crashed into me. Poppycock clipped my back with her hips as she ran past in a tizzy. Bella did the same thing, only harder. Bucket whimpered and dove under my legs. Igor came in two minutes later, looking seriously dementedÔÇöand moving at a full gallop.

His 70 poundsÔÇömoving at 20 miles per hourÔÇöknocked me off my perch and into Bucket, and all of us tumbled down the slope. I popped upright and saw Bella and Poppy running beside me, and we all went boing-boing and pell-mell and straight down. We bottomed out and kept going and ran across an arroyo … and that's when I noticed that Igor was missing. He'd been beside me only a moment ago, but how long ago was that moment? Two seconds? Ten? A minute? I stopped and called and waited and called and ran up and down the canyon. No Igor. I tried to backtrack using paw prints, but the snow was coming down too hard and there was no trail left. Igor had gotten lost once before and headed home. Maybe, I hoped, it had happened again.

But he wasn't at home, so Joy and I hiked back to the Thumb. The storm got worse. We hunted all day, into the evening, the temperatures dropping below freezing, but we never found him.

It was a terrible night. The uncertainty, the helplessness, the sense that I'd been given fair warning but had chosen to ignore it. We'd promised the dogs that their last memories would be of love. I had visions of Igor dying alone, scared and cold and missing his familyÔÇöthe exact opposite of my vow.

WE FOUND IGOR ALIVE the next day, with serious help from our neighbors. People had poured inÔÇöpet owners, dirt farmers, gangbangersÔÇöto join our search. Pretty soon, there was a message on our machine from a guy who lived about five miles down the road. Igor, he said, was standing on a cliff across from his front door. We hopped in the truck and roared over there. Almost immediately, we spotted him. I pulled over and jumped out. Igor saw me but didn't move. Instead, he shook his head, lowered his gaze, and started trembling. I wasn't sure what to do, so I dropped to my knees. He stared at me for a long time, then finally came over, his head low, his tail tucked. He looked like he'd done something very wrong.

Igor had frostbite on his paws, slashes across his belly and backÔÇöfrom what, we didn't knowÔÇöand he needed about three days to sleep it off. Unfortunately, when he woke up he was a different dog. At first, whenever we walked into the backcountry, he'd wander off and find a high perch and gaze at the Thumb. Pretty soon, he just wandered off.

Then the change crept into his home life. Bucket was still his best friend, and they still liked to wrestle, but now Igor had misplaced his self-control. He was hurting Bucket, throwing him around too much, biting him too hard. Then he bit me. I was walking down to the back field one day and Igor ran up behind me and took a chunk out of my thigh.

It happened again later that weekÔÇöa surprise bite on my fingersÔÇöand I didn't know what to do. I told people the story and they all said the same thing: It's a different world in the badlands. Maybe he met something weird out by the Thumb.

The morning after the last of those conversations, Igor nearly killed a small dog of ours named Buddy. By then, after consultation with several vets and rescuers, we believed we knew what was wrong. Because of the inbreeding required to produce all-white bull terriers, they're often prone to epilepsy, and because of the epilepsy they're prone to Rage Syndrome, which is like an epileptic fit featuring rage instead of the shakes. There's no treatment for it and it's progressive. Fits last longer, violence escalates.

There was only one thing to do. We called our vet, scheduled euthanasia for the next morning, and had another very bad night. I got up early to take Igor for one last Five-Dog WorkoutÔÇöthe very game I'd invented for him in the first place. I brought Poppycock and Bella and Bucket. We ran Coyote's Line again that day. Igor and I leapt the cornice and landed and bounded down together, and for those few seconds of primordial reenactmentÔÇöjust a man and a dog at playÔÇöeverything did change, the way it always has. But then the moment was gone. There would be no magic out there this time, only disappointment.

THAT DISAPPOINTMENT turned to despair when we reached the bottom of the cliff and I noticed Poppycock was missing. I called and searched, but she wasn't to be found. It was getting late; the vet would be at our house any minute. Having to hike out of the backcountry to go euthanize a dog and then having to turn around and come back to hunt another is the kind of heartbreak only animals can provide. But there were no other options. Animal rescue might be a game of death, but isn't everything? Tomorrow I would wake up and try to save some more dogs regardless, and the day after that as well. Joy put it best: This is what we do.

Right about the time I realized that, I spotted Poppycock. She was hovering at the edge of the badlands, standing beside a juniper bush, acting like dogs act when they've just buried a boneÔÇöas if she had something to hide. The other dogs weren't paying much attention, but there was a tingle down my spine and the hair on the back of my neck stood up. I took about ten steps forward and glanced behind a juniper bush. Sitting there, less than ten feet from me, was the coyoteÔÇöthat coyote, the coyote of Coyote's Line.

He was enormous, almost a hundred pounds. His face wide, his shoulders broad, his coat two-toned. He looked like a hybrid, like a dog, wolf, and coyote all rolled into one. He looked like the standard-bearer for the entire canid line. We got a good, long look, because he wasn't running away; in fact, he didn't even appear to be afraid of us. Instead, he sat straight up, positioning his torso directly over his hind legs, and thenÔÇöI kid you notÔÇöhe started hopping on those hind legs, hopping like a kangaroo.

It was the most bizarre thing I'd ever seen an animal do. I didn't know how to react, so I stood there gaping. The coyote hopped in a semicircle, his great jaws hanging open, his tongue flopping. When he stopped, we were all standing in a long line: The coyote at one end, Igor at the other. He'd stopped a few feet from Poppycock but ignored her and started walking toward me. He passed me and then Bella and Bucket and stopped in front of Igor. They stood a few inches apart for what seemed like an eternity. Then the coyote leaned in close and rubbed his head against Igor's neckÔÇöthe same gesture wolves sometimes use when adopting a newcomer into their pack. They stood together for about 20 seconds and then, with some silent signal I never detected, the ceremony ended. In three quick lopes, the coyote was gone, vanishing in the distance, becoming another backcountry apparition, another story no one quite believes yet no one entirely doubts.

Trickster, shape-shifter, transformerÔÇöthat's how most cultures view the coyote. He is the keeper of magic, the bringer of death, the gateway to renewal. His presence, according to many, carries with it specific lessons. Ted Andrews, an expert on the subject, put it this way in his book Animal-Speak: “The coyote teaches the balance of wisdom and folly and how both go hand in hand. … Are you not seeing the wisdom in your life and events? The coyote will help you.”

I certainly needed the help. Igor was dead within the hour. Joy made it through all right, but I took a couple of extra days to get going again. Bucket hasn't been the same since. All things, as they say, are connected, but that doesn't make them any easier. Or any more comprehensible.